Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

In good weather, Shibhu walks 20 minutes to work at a Canada Post mail processing plant in eastern Toronto near Lake Ontario. In bad weather — be it freezing rain, snowfall or extreme wind — she’s “at the mercy of the transit system.”

Shibhu, who asked to be identified by her first name only, has worked for Canada Post for 16 years. When she started, she was living in an apartment in central Toronto and commuting two hours to a facility in neighbouring Mississauga, Ont., to make her evening shift.

Five days a week, she’d leave home at 4 p.m. and take the Toronto subway all the way west to the end of the line. Then she’d pay another fare and get onto Mississauga Transit, taking a 40-minute two-bus trip the rest of the way. If the transfer between the two buses took too long, she’d take a taxi. When her shift ended at 11 p.m., nearby buses would no longer be running, so she’d hitch a ride with a colleague to a stop where a bus was still in service and wait there. She’d get home at 1 a.m.

That was her routine for three years. Since then, Shibhu has been transferred to a centre closer to her current home, but the journey is often still lengthy. Her evening shift runs from 3 to 11 p.m. If she can’t walk, she takes a bus and then a streetcar. On the way back, she’ll take a longer route with multiple buses to try and avoid waiting outside alone.

“Every night, I’m the only one on the bus,” said Shibhu, who is in her 50s and often has back pain. “If I miss it, I have to wait 30 minutes. I can’t take any overtime because there’s no transit after 1 a.m.”

Shibhu wishes transit was faster and more reliable. She wishes for shorter wait times, especially at night, and for transit services targeted at people like her, who work odd and late hours. She wishes she didn’t have to choose her shifts — sometimes losing overtime pay — based on bus schedules.

“Drivers aren’t dependent on anything, but I don’t drive,” Shibhu said. “I’m tired but I don’t have any other choice.” If the weather is really bad and her husband isn’t around to give her a ride, she sometimes misses work altogether.

Last month, Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government announced that it was returning $1 billion to the province’s more than 8.3 million drivers by cancelling licence plate renewal fees. The cost of a new plate sticker depends on where you live: in southern Ontario, the cost is $120 per year, while in northern Ontario, the fee is $60 per year.

As Doug Ford’s caucus reaches the end of its four-year term, few similar investments have been made in short-term boosts to public transit services that could make life immediately easier for transit users like Shibhu.

That $1 billion could have funded temporary reductions in transit fares, for example, said environmental economist Dave Sawyer. It could have been spent on permanent changes like an increase in rapid bus service lanes, which he said would cost less than $100 million to implement. Such policies could have beneficial impacts for workers that are heading back to offices in full force, many turning to transit in the wake of increasing gas prices due to the war in Ukraine.

Instead, the sticker cancellation is “buck-a-beer, but for drivers,” said Sawyer, who works with the Canadian Climate Institute. That’s a reference to Doug Ford’s campaign promise prior to his 2018 election to lower beer pricing in the province — a tactic aimed at attracting voters through individual financial incentives, eliminating revenue from provincial coffers while having no clear public policy impact.

In the lead-up to the imminent Ontario election, many of the Ford government’s transportation policies and promises appear similarly aimed at winning over cities in what’s known as the 905 — the cluster of suburban jurisdictions outside Toronto where provincial and even federal elections are won or lost, and where transit options are few and driving is the norm.

The government has long promised to expand highways to unclog congestion, despite studies showing that more roads simply attract more drivers. This April, it is scrapping highway tolls on two roads in Durham Region, east of Toronto.

And last week, Ford dropped a massive $82 billion transit and transportation plan for the next two decades that mentions “bus service” only six times, versus 107 mentions of “highway.” Highly focused on roads and cars, it’s unlikely to have material benefit for Shibhu and those like her — a fact she is well aware of.

“I get it, because there are few people who ride the bus at night so there’s no need to increase bus services after 10 p.m.,” she said. “But if I didn’t have to wait 30 minutes after my shift is over for a bus and I could get home in 30 minutes, I could do more for my house and my community.”

The Ford government’s relationship with transit is complex. Shiv Ruparell is a senior policy and public affairs officer with the Canadian Urban Transportation Association, an advocacy organization that represents public transit authorities across the country. He said the Ford government has been “the most accessible government” to work with on transit projects at all levels across Canada. It has funded major transit projects across the province, including $28 billion for four new lines in Toronto.

The government has also announced plans to extend and electrify GO Train commuter services across southern Ontario. It also reduced fares in the 905, and ended double fares for riders switching between services run by different municipalities, which would have saved Shibhu about $9 a week when she was commuting to Mississauga. These are rare instances of transportation policy with wide and immediate benefit.

The Progressive Conservatives are also committed to a long-awaited new light rail transit line in Hamilton, Ont., albeit after delaying it significantly. In late 2019, the Ford government cancelled the billion-dollar project, saying it would cost taxpayers too much money. It then set up a task force to find alternative uses for the money — but eventually, the task force recommended rapid transit. So last May, the project got greenlit again, with the province and the federal government each committing $1.7 billion.

Ontario also extended operational support and bailouts to transit agencies at the beginning of the pandemic, when ridership dropped by 95 per cent. That, and the ongoing investment, was something of a surprise to Matti Siemiatycki, an associate professor of geography and planning at the University of Toronto who leads the School of Cities. “Even this government, while signalling for major plans of a car-based future, remained steadfast in their commitment to mega-transit projects,” he said.

But it’s a very specific vision of what transit is, he adds: mostly underground projects that don’t interact with streets or reduce lanes for car traffic. “They’re mostly off-road and sometimes at huge expense,” Siemiatycki said, noting that bus services have likely not been prioritized because they take up road space.

“A real strategy would anticipate growth, look ahead to where it’s going to be and invest accordingly,” said Jason Allen, a 10-year veteran of the public transit industry who lives in Hamilton. Instead, he said, “the Ford government is largely reacting” to what it thinks will earn public favour.

This vision of transportation — one that prioritizes roads even when considering climate change mitigation — is illustrated in the plan released last week.

On one hand, transportation is recognized as Ontario’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 36 per cent of all emissions in 2019. The need for drastic reductions is acknowledged, with a pledge to build a low-carbon transportation system to help meet Ontario’s overall emissions reduction target of 30 per cent by 2030, based on 2005 levels.

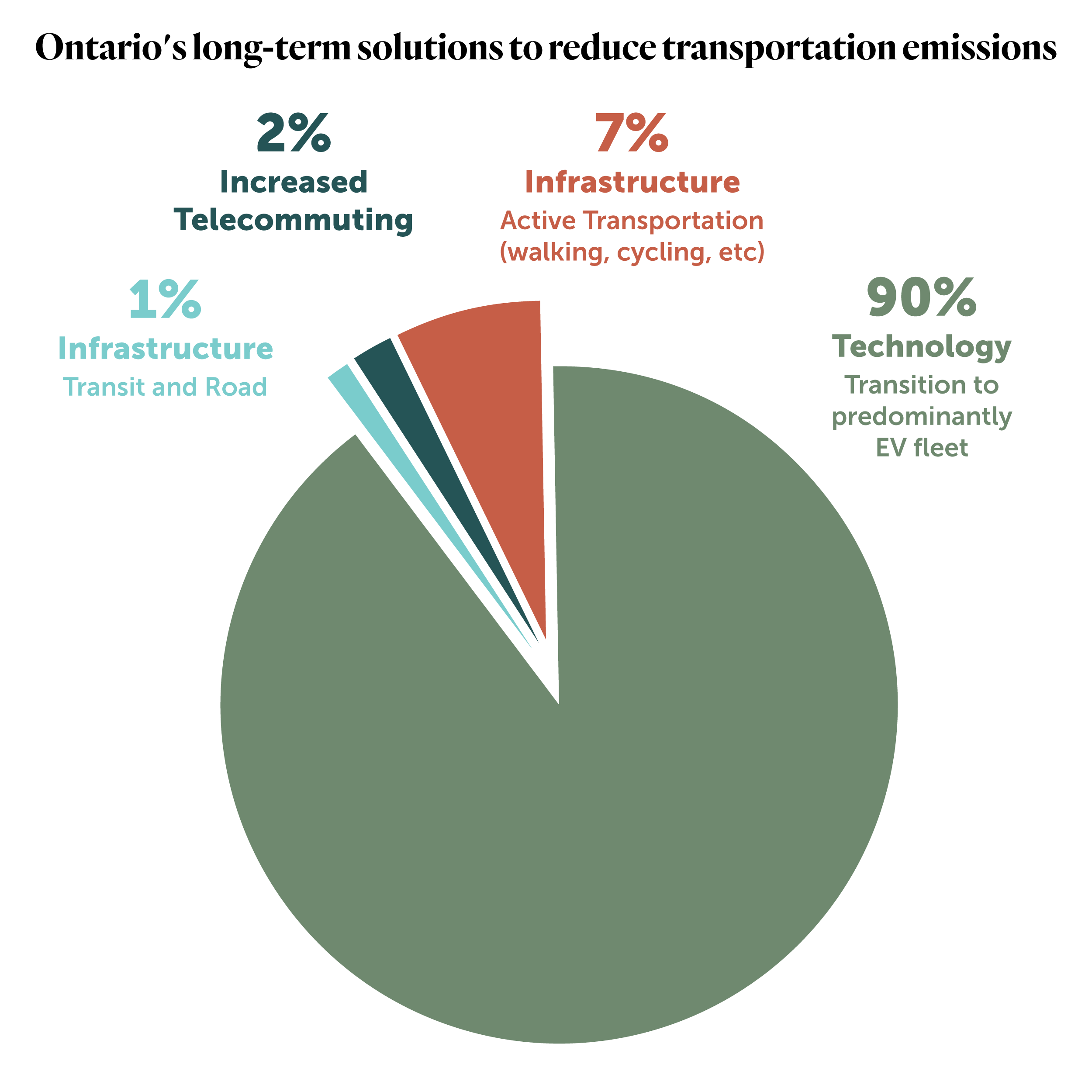

But the expectation is that 90 per cent of transportation emission reductions will come through transitioning to electric vehicles by 2051, with the government betting that retooling Ontario’s existing car manufacturing facilities will boost supply and sales naturally. Only seven per cent of emissions reduction targets are through investments in active transportation, such as walking and cycling. Converting drivers into occasional or regular transit users is barely mentioned.

“It maintains a pretty consistent theme from this government, which prioritizes private vehicle usage above all else and envisions a future where people continue driving,” said Ian Borsuk, co-ordinator with Environment Hamilton and member of the Hamilton Transit Riders’ Union steering committee. “People will still be sitting in traffic but in a Tesla or a Chevy Volt.”

“They’re locking us into the way we’ve been doing things over the last few decades despite the evidence that we should be radically changing the way we move,” Borsuk said. An increase in telecommuting and infrastructure investment, for example, is set to account for only three per cent of reductions, even though the past two years have demonstrated that working from home is a viable option for many.

Moaz Ahmad, a long-time transportation consultant, said that for the Ford government, policies that prioritize transit users are “second place.” Road tolls, for example, can be removed in a day, while the Ford-backed transit projects have been “decades in the waiting” and will take as long to complete. “We need to get co-ordinated policies today if we’re going to do anything to connect the province and do something about climate change,” Ahmad said.

Even as the Progressive Conservatives promise all sorts of investments, the money isn’t actually flowing into transportation yet. According to the latest expenditure report by Ontario’s Financial Accountability Officer, the province spent just four per cent of its $630 million budget for municipal transit projects and just 16 per cent of the Ministry of Infrastructure’s entire $1.2 billion budget in the 2021-2022 fiscal year. This leaves many questions unanswered about the actual funding mechanism to pay for the Ford government’s big transportation projects, as well as when they’ll actually begin.

Siemiatycki said the government has been able to make “seemingly contradictory announcements” that trumpet investments in both highways and transit in part because the pandemic created a precedent for governments to borrow a lot of money. This in turn eliminated the trade-off generally associated with creating big transportation policies, where budget limitations force a choice between cutting individual costs, such as the licence plate renewal fees, and making big investments. Now, governments can say they’re doing both.

“You can now cut a billion-dollar vehicle registration tax but still announce an $82 billion transportation strategy,” Siemiatycki said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits