Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

On a rainy October morning, a small boat heads north from Campbell River, B.C., threading through Discovery Passage en route to an inlet called Phillips Arm.

As we near our destination 90 minutes later, the rain slackens and the forested lands jutting out of the water come into focus. On a rocky outcrop, California sea lions lounge.

We have come to visit the traditional territory of the Kwiakah (KWEE-kah) First Nation, once one of the largest bands in what is now British Columbia. But today it is one of the smallest, with just 22 members remaining.

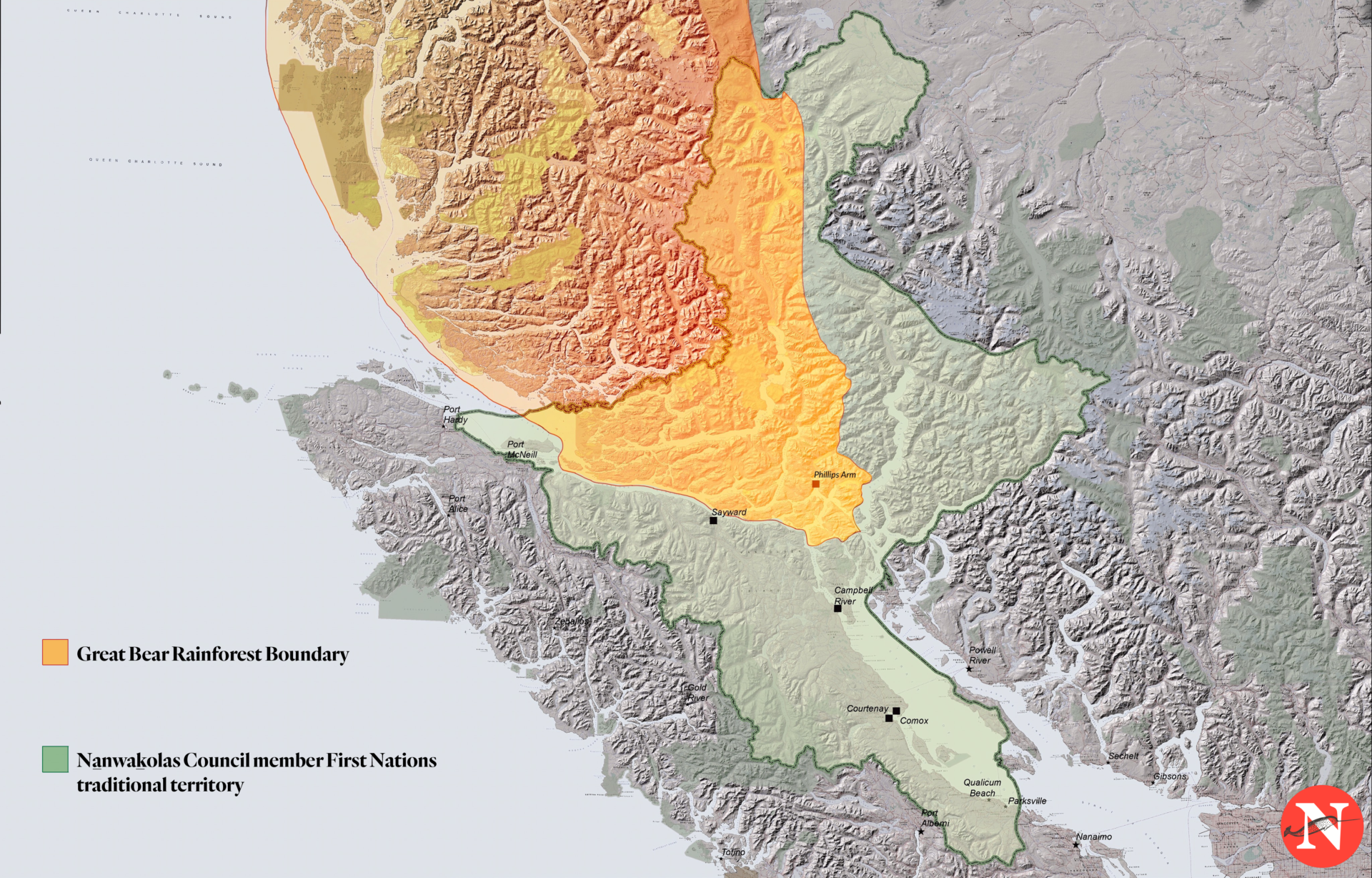

Their territory lies within the Great Bear Rainforest, a 6.4 million hectare planning area created in 2016, of which a little more than half is forested.

It is touted by the province as a “gift to the world” for protecting 85 per cent of those forests.

But the Kwiakah, in the far south of the designated area, say that, under the agreement, logging in their territory will increase, and that this deal negotiated by the timber industry, province, environmental NGOs and First Nations — 20 years in the making — came largely at their expense.

Disembarking, we walk over ferns and a creek near the Kwiakah’s roughly 20-hectare reserve at the site of an old village called Matsayno. During Matsayno’s heyday, the Phillips River was full of fish, including all five species of salmon, and people hunted grizzlies, mountain goats and other game.

Chief Steven Dick, who has led the Kwiakah for about 35 years, welcomes us to Kwiakah land.

“There were hundreds of people who lived here if not a thousand,” he said. “So it’s very important to the citizens of Kwiakah.”

These multitudes declined as people transferred to other nations, were lost in war with other First Nations and died from diseases brought by settlers, he said. Today, most of the remaining Kwiakah live in or near Campbell River on Vancouver Island. They left their territory in the 20th century in pursuit of jobs and services, after early clearcuts on their land and overfishing in their waters, which led to a provincial ban on local fishing.

But now the Kwiakah want to return to their old village site and set up a camp here, says Chief Dick, so they can reconnect with their land. His top priority for his people is “a secure land base where they could have their own community…to have a place where they can call home.”

A 2009 provincial land use order said that timber company Western Forest Products would be allowed to cut 27,000 cubic meters annually from the Kwiakah’s core territory in Phillips Arm. But under the Great Bear Rainforest agreement, B.C. Chief Forester Diane Nicholls gave Western permission to cut 41,600 cubic meters annually — 54 per cent more — in the area.

Then things turned even darker for the Kwiakah.

Last year, Western petitioned the B.C. Ministry of Forestry, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations to combine two timber licences it holds in the Great Bear Rainforest, which would theoretically allow it to cut 275,000 cubic meters annually from Kwiakah land, said Jeff Sheldrake, executive director of regional operations for the B.C. ministry.

A decision has not yet been made on Western’s application, he said. “But Kwiakah’s concern has been well noted.”

Although it may seem strange that an area touted for conservation would continue to allow logging, that is typical in Canada, where extractive industries dominate the economy.

In fact, ecosystem-based management, a logging practice meant to ensure that the whole ecosystem continues to function, still allows for clearcuts. Profit sharing with First Nations, whose trees these were originally, means they might get three to five per cent of the government’s share of profits.

That income for First Nations is part of the justification for allowing continued logging in the Great Bear Rainforest: it brings remote communities economic opportunity. Nevertheless, most First Nations that have territory within the Great Bear Rainforest boundary support the agreement in part because it reduced logging potential on their lands. But the Kwiakah territory is now at risk for increased logging, making it harder for them to get past the premise that the Crown controls their lands and sees them first as a timber resource.

The boundary of the Great Bear Rainforest dips down into the traditional territory of the Nanwakolas Council of member First Nations, of which the Kwiakah First Nation is a part. Image based on maps from the Nanwakolas Council and the province of B.C. Image: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“These trees belonged to the nations who lived here,” said Frank Volker, manager of economic development for the Kwiakah. “The government steals the trees from the nation and sells them to a licensee [timber company]. The only reason why that is legal is because the government who is committing that ‘crime’ makes it legal. But that doesn’t make it OK.”

We are walking the boundary between the reserve and Western’s Tree Farm Licence 39, cutblock five, and some of the trees wear orange tags. Later, cocooned in the forest, we hear a helicopter pass directly overhead, perhaps doing early reconnaissance, said foresters in our group.

So why did the Kwiakah end up with such a bad deal?

Much more of the northern Great Bear Rainforest is now off-limits to logging under the agreement, but primarily because it is steeper, more remote and much more expensive to get logs to market. The south has more “valley bottom” habitat close to the water, ideal for timber harvesting, said Sheldrake.

“Parts of GBR [Great Bear Rainforest] do not contain any economic timber value,” he said. Industry is first interested in places where logging makes the most economic sense.

The Kwiakah also say they were excluded from the Great Bear Rainforest negotiations. An umbrella Indigenous group, the Nanwakolas Council, was negotiating on their behalf.

Chief Dick said the Nanwakolas Council kept the Kwiakah in the dark. “They told us about the deal just a few days before it was signed,” Chief Dick told The Narwhal. The Kwiakah rejected it, but at that point it was too late to make changes.

Dallas Smith, president of Nanwakolas Council, disputed the Kwiakah’s claim that they were excluded.

What’s undisputed is that, when the Kwiakah refused the deal, the provincial government began to talk with them directly, said Sheldrake.

Another problem is that the provincial government had a two-tier system in engaging with First Nations, said Jody Holmes, project director for Rainforest Solutions Project and one of the main environmental NGO negotiators of the Great Bear Rainforest deal. Groups “in the tent” had signed a strategic engagement agreement (SEA) with the province. Groups that hadn’t were termed nonaligned or nonparticipatory.

“They would withhold treats to try to get them to come in,” Holmes said. She estimated six to nine nations were non-aligned throughout the Great Bear Rainforest process.

Ultimately the Kwiakah signed a Strategic Land Use Planning Agreement (SLUPA) with B.C., which paid them $380,000. But that money is not a payment to the Kwiakah for logging in their territory, said the Kwiakah’s lawyer, Drew Mildon, with Victoria-based Woodward and Associates. It is intended to give the Kwiakah the resources they need to engage in administrative duties that forestry requires in B.C., such as consultation.

“Kwiakah have not agreed to any areas or cut rates,” Mildon said. “They have taken the position that the annual allowable cut in the Phillips [area] set by the Crown is unreasonable and does not sufficiently protect wildlife.”

Volker added that the Kwiakah signed the Strategic Land Use Planning Agreement because their consent was needed to finalize the Great Bear Rainforest deal and they support its principle: an attempt to conserve the rainforest. And their lawyer Mildon advised them that signing did not mean that they were agreeing to annual allowable cut rates in the Phillips Arm area.

However, the province has a different legal interpretation: signing on to the Strategic Land Use Planning Agreement is viewed as the Kwiakah’s acknowledgment of the Great Bear Rainforest Land Use Order, Vivian Thomas, communications director for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, told The Narwhal.

The province stopped short of saying explicitly that the Kwiakah had agreed to the annual allowable cut in the Phillips.

The dustup between Nanwakolas Council and the Kwiakah does raise the question of whether the Kwiakah had the opportunity to give informed prior consent, as is required, Holmes said.

Volker added despite the confusion, one thing is clear: the Kwiakah did not consent to the annual allowable cut rate.

The advice given to those concerned about the fate of the land by Jeff Sheldrake, the regional director of B.C.’s Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, is to “sit down and work hard at this landscape unit reserve design process” in which industry and First Nations negotiate with each other.

And yet, considering the ongoing concern that the province set First Nations on a collision course with companies by assigning industry cut rates on band territories, that position could be read as dismissive.

The landscape unit reserve design process was sold as a great opportunity for First Nations to influence how their land is managed and establish reserve areas where no logging should occur, Volker, manager of economic development for the Kwiakah, said.

“In reality it is a complicated and very expensive process that was designed with licensee [timber companies] interests in mind — not the interests of Indigenous peoples” or the environment, he said.

Chief Dick agreed.

The areas the province and industry identified to protect were in places “they’re not going harvest anyway,” he said. “There’s no need to protect those areas because they’re not at risk.”

On the other hand, the lower valley, which the Kwiakah want to protect — where timber is easily accessible and close to shipping routes — “they’re not wanting to use that area as protected,” Dick said.

Volker said he thinks this process is “designed to be very difficult to understand to make sure the average Joe doesn’t get it and won’t complain or identify the flaws.”

To sift through its complexity, they hired a forestry consultant. The Kwiakah are taking a stand in the Phillips Arm area, the most important area in their traditional territory, and have already “spent tens of thousands of dollars” engaging in the design process, said Volker.

But they aren’t close to done or optimistic about the final result. And while there are three additional landscape units in their territory, “Any large scale participation of Kwiakah in the LRD [landscape unit reserve design] process for those landscape units was just cost prohibitive,” said Volker.

“We just cannot afford to be active at the same level as in Phillips.”

Later in the day, the sun glances off the Phillips River, reflecting a spotlight onto our group in the otherwise dark forest. In the distance a grizzly bear gallivants into the water, swinging a giant salmon in his mouth.

This grizzly and his relations are a source of income for the Kwiakah. Beginning in 2007, they partnered with nearby Sonora Resort, which pays them an annual fee to take guests to see bears from boats and viewing platforms.

That business is threatened by the proposed logging. Phillips Arm has seen a lot of industrial activity already; poorly executed clearcuts from earlier times were devastating, especially to salmon habitat. Modern clearcuts continue.

Back on the boat in the afternoon, the sky turned blue. Clear cuts of differing ages are visible on the slopes all around us, giving the landscape the look of an uneven haircut.

An important point to note in all of this, Volker said, is the Kwiakah aren’t against all logging.

For example, they signed an agreement with the province in 2018, which acknowledges the impact on Kwiakah rights and title from logging and the lost income from bear viewing due to the industrial disturbance. To compensate them for this loss, the province is allowing the Kwiakah to apply for a forest licence to harvest 30,000 cubic metres (once, not annually).

Ideally the Kwiakah would be able to find this volume in its own territory, Volker said, but they will not cut one tree from Phillips Arm. Not that they could: it is almost entirely licensed to big timber companies. Instead, they have to find an area assigned to a timber company but not yet licensed for cutting and convince both the company and any First Nation with overlapping rights to allow them to cut. Because of these hurdles, the Kwiakah may never see much in the way of profits.

Separately, Western talked about condensing five years’ worth of logging into 18 months, which would leave three-and-a-half years without bear-disturbing industrial activity. The Kwiakah are also pushing for Western to reduce its annual cut for those five years from 41,600 cubic meters to 10,000.

The bottom line is that the Kwiakah don’t think Phillips Arm can tolerate the levels of logging the province has authorized. That conclusion is based on independent scientific studies they commissioned to measure the health of their salmon and bear populations.

Biologist Wayne McCrory, an independent consultant hired by the Kwiakah, is a veteran of more than 30 years of grizzly research. He conducted direct counts of individual bears based on four research trips to Phillips Arm.

“It’s the most messed up watershed I’ve ever seen.” — Biologist Wayne McCrory

In historic times he estimates the watershed likely supported 50 to 60 grizzly bears. But his research concluded that there are just 10 to 12 bears there today — numbers corroborated by another study using DNA hair snagging and remote cameras.

The cause of the grizzly population decline in the Phillips Arm area is primarily clear-cut logging, he said. Logging roads disturb critical grizzly habitat, and massive clear-cutting too close to salmon streams caused landslides, destroying spawning habitat.

“It’s the most messed up watershed I’ve ever seen,” said McCrory. Part of the Great Bear Rainforest order calls for identifying watersheds that need recovery and doing restoration.

“In order to do that, you don’t keep clear cutting,” he said. “For a watershed that’s been so — pardon my language — fucked over by the timber industry, they should just leave it alone for 20, 25 years and let it recover and do some restoration.”

The Kwiakah and Western Forest Products have been negotiating, but the Kwiakah feel burned by previous dealings with the company. The band remains concerned about Western’s application to amalgamate its Tree Farm Licences, which would allow it to potentially harvest its full 275,000 cubic meters annually from Phillips Arm.

In an April letter, Western assured Mildon, the Kwiakah’s lawyer, that, until 2026 when the province adjusts annual allowable cuts, it would not take more than the 41,600 cubic meters annually designated for its Tree Farm Licence that includes Phillips Arm.

In an e-mail, Seanna McConnell, director of Indigenous engagement for Western Forest Products, reiterated, “We will not harvest all of the annual allowable cut from a single geographic location. We will continue to maintain the partition on harvest from the Phillips and Broughton blocks of the TFL [Tree Farm Licence] once amalgamated.”

Despite the assurances, the Kwiakah have little trust in Western Forest Products.

And there’s reason for those misgivings: starting in 2013, Western was negotiating with the Kwiakah to reduce cut levels in the Phillips to 15,000 cubic meters a year and drafted a letter to the province, proposing this solution.

But in an overlapping time period from 2011 to 2014, the forest industry as a whole was negotiating with environmental non-profits. As of 2014, negotiations included a proposal to lift restrictions on logging in the Phillips in exchange for reduced logging in the Great Bear Rainforest as a whole, said Holmes of Rainforest Solutions Project.

“Neither the NGOs or Kwiakah First Nation were aware of the coexistence of these simultaneous and potentially conflicting negotiations with WFP [Western Forest Products],” she said.

Meanwhile, Western was also lobbying the province to increase the cut for the amalgamated Phillips and Broughton areas to 79,000 cubic metres a year, which the company could log entirely from Phillips.

“We learned about their betrayal in April 2016 when staff in the B.C. Chief Forester’s office informed us that she wanted to move forward with a decision on the new AAC [annual allowable cut] but had not consulted with Kwiakah,” Volker said.

Holmes acknowledges that the changes NGOs negotiated in ecosystem management — meant to protect at least 70 per cent of each type of ecosystem across the Great Bear Rainforest — ended up increasing the amount of logging allowed in Phillips’ valley bottom ecosystem.

In an October 2016 letter to Western Forest Products, Chief Dick wrote, “Kwiakah has worked in good faith to try and reach an agreement with WFP, only to end up feeling we have been duped into investing thousands of dollars and our time and energies in an attempt to negotiate with someone who appears to have never had any intention of reaching a fair agreement with us.”

Hoping to circumvent further struggle, Chief Dick proposed to buy out timber harvest rights in the Phillips.

“We weren’t prepared to enter into those sales negotiations,” Western’s McConnell said they responded via letter.

That reaction didn’t surprise Volker. Citing a price would create poor optics, he said, giving the Kwiakah the opportunity to say, “That’s what these guys think they can charge us for our own trees.”

After decades of advocating for his people, Chief Dick said he is impatient with the pace of change in Canada with regard to Indigenous people.

“I want to see that big shift,” he said, like the Maori, whose claim to self-determination is better recognized by New Zealand. He hopes some of that change will come about by the 10-year review of the Great Bear Rainforest agreement in 2026.

“I hope the political landscape within this province as well as in Canada changes to really take in to consideration the view of First Nations,” he said. “I mean, you’ve got this United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People — which Canada adopted — and I’m hoping to see those types of approaches be taken seriously.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits