‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

First Nations in coastal B.C. estimate they will create 3,000 jobs and generate $750 million in investment over the next 20 years by building up industries such as sustainable fisheries and renewable energy — supported by an investment of $335 million that was made official on Tuesday.

The agreement, called the Great Bear Sea Project Finance for Permanence, includes 17 First Nations, the B.C. and federal governments and investors. It’s part of Canada’s previously announced $800-million commitment to invest in long-term funding for Indigenous-led conservation. The Great Bear Sea, also called the Northern Shelf Bioregion, is adjacent to the Great Bear Rainforest, a largely protected area on the central coast of B.C. that covers 6.4 million hectares.

Heiltsuk Chief Councillor and president of Coastal First Nations K`áwáziɫ (Marilyn Slett) said she’s excited some of the funding will go towards teaching Heiltsuk youth about the land and waters. The investment is intended to bolster First Nations stewardship over their waters.

“It’s being led by our communities, our communities are doing the work,” Slett said in an interview. “This is something that we’re really proud of.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and a number of federal and provincial ministers attended a celebratory announcement in Vancouver on Tuesday morning.

“Today’s announcement is an important step in our governments’ efforts to collaborate on and advance Indigenous-led projects that will protect the health of our marine ecosystems for future generations. We will continue to work together with Indigenous and coastal communities from coast to coast to coast to ensure Canada’s marine and coastal areas remain healthy, clean and safe,” Trudeau said in a statement.

As part of the agreement, Coastal First Nations and Na̲nwak̲olas Council, two organizations that bring together member nations for collaboration, will provide administrative support, Coastal First Nations chief executive officer Christine Smith-Martin said. Coast Funds, an Indigenous-led conservation finance organization, will manage the funds. For Smith-Martin, the funding comes at a critical moment for the marine environment.

“We’re seeing this alarming decline of fish and wildlife and habitat, such as kelp forests. We’re losing key species of fish and shellfish such as crawfish, eulachon and abalone. Marine mammals such as whales in our communities are showing up on the shore, and a lot more than we would have anticipated, and dolphins and sea otters,” Smith-Martin said in an interview.

“We have an opportunity right now to make a difference.”

The 17 participating First Nations are Haida Nation, Gitga’at First Nation, Gitxaała Nation, Haisla Nation, Kitselas First Nation, Kitsumkalum Band, Metlakatla First Nation, Heiltsuk Nation, Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, Nuxalk Nation, Wuikinuxv Nation, Da’naxda’xw-Awaetlala Nation, K’omoks First Nation, Kwiakah First Nation, Mamalilikulla First Nation, Tlowitsis Nation and Wei Wai Kum First Nation.

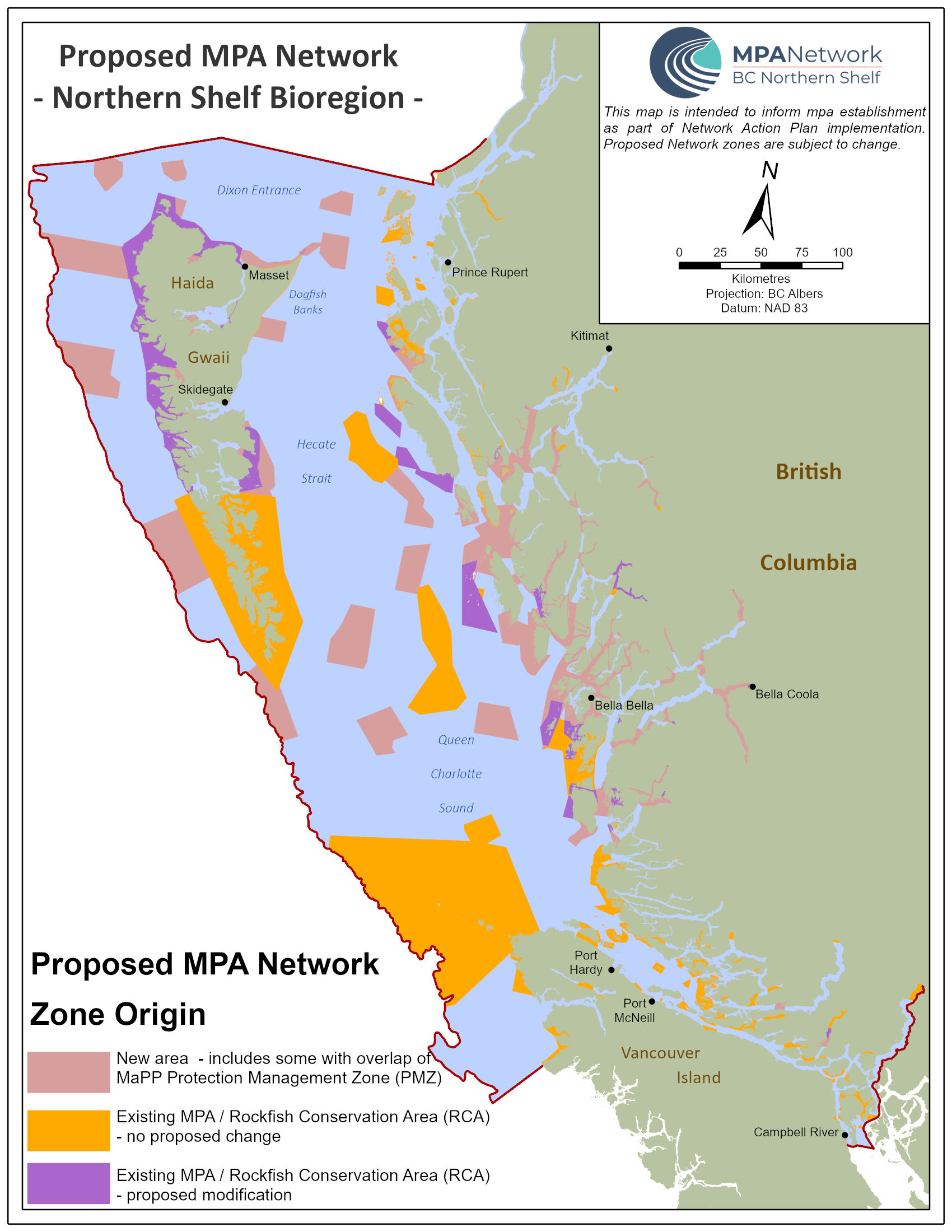

The investment will also support establishing the network of marine protected areas in B.C, announced by First Nations, the B.C. government and the federal government in February 2023. The network will be a mosaic of protected areas with individual management plans tailored to specific waters, communities and industries. It will eventually protect approximately 30,000 square kilometres — or 30 per cent of the Great Bear Sea — just under the size of Vancouver Island. According to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 62 per cent of the proposed network is already protected.

Alternative economies are top of mind for First Nations partners in the Great Bear Sea, particularly on the heels of the federal government’s announcement of a ban on fish farms, which will come into effect in B.C. in 2029. However, Slett said this agreement is not connected to the transition away from fish farms and emphasized the protected areas network will not shut down commercial fishing. Management plans are being created in consultation with industry stakeholders, she said.

“We understand the importance of fisheries,” she said. “Our people have depended on [fisheries] for an economy. The work we’re doing here is about being able to sustain that economy into the future.”

Many salmon populations in the province have plummeted, which scientists attribute to a multitude of factors including warming waters and worsening drought, pollution and lice from fish farms and poor forestry practices that have degraded habitat. According to the Pacific Salmon Foundation, Fraser River sockeye have declined 54 per cent in the past decade. Skeena River sockeye have declined 75 per cent since 1913.

Salmon fisheries require a functioning ecosystem, Slett said.

“There’s a lot of work to do to bring the resources back into abundance so everybody can enjoy them.”

The project finance for permanence model has been around for almost two decades, with roots in the 2006 Great Bear Rainforest agreement. Also used in conservation projects in Brazil and Costa Rica, the model is designed to support large-scale, long-term projects.

The initial funding of the Great Bear Rainforest, which included $120 million from conservation groups, philanthropists and provincial and federal governments, yielded significant economic and environmental benefits. “We protected vast areas of ancient temperate rainforests, created nearly 1,300 jobs, launched over 130 new businesses and raised household incomes across the region. And we were just getting started,” Dallas Smith, president of Na̲nwak̲olas Council, said in a statement.

Smith-Martin said conservation funding in the Great Bear Rainforest allowed people to transition from careers in logging to other industries, such as eco-tourism.

Prime Minister Trudeau first announced this new investment in 2022, when Canada hosted the United Nations’ biodiversity conference in Montreal, committing $800 million in funding for four Indigenous-led conservation initiatives. Tuesday’s announcement celebrates the official signing of the agreement to invest in the Great Bear Sea.

A similar agreement between Indigenous and Canadian governments is almost finalized in the Northwest Territories, which would see at least $100 million invested in the Northwest Territories Project Finance for Permanence. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, the funding could help governments double conserved areas in the territory, and contribute 2.5 per cent or more towards Canada’s commitment to protect 30 per cent of the country’s land and inland water by 2030.

More than 5,000 marine protected areas exist around the world, protecting about eight per cent of oceans. They are considered critical for safeguarding biodiversity and protecting fragile ecosystems.

Slett said long-term funding is key to completing the west coast network. Short-term funding is more widely available, but creates uncertainty for projects and people, as organizers must seek out renewals or new funding sources every few years.

“This will help our communities immensely,” Slett said.

Smith-Martin said when she travels for conferences, people around the world say they’re paying attention to agreements being reached in the province.

“It kind of took me aback when I was in New York to know that so many communities and so many different countries know about the work we’re doing here, not just in Canada, but specifically in British Columbia, which I think is something that we all should be very proud of,” she said.

Updated on June 26, 2024, at 1:15 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to clarify in a photo caption that both Hím̓ás Wigvilhba Wakas (Hereditary Chief Harvey Humchitt) and Dallas Smith, president of Na̲nwak̲olas Council, are pictured meeting Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, as the previous caption only identified one of the two leaders. It has also been updated to clarify that the Great Bear Rainforest is not protected entirely, but largely, through a mix of protections and sustainable management. And the headline has been updated to remove language stating the $335-million is entirely federal funding, when in fact it is from the B.C. and federal governments, as well as other investors.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...