The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

Hím̓ás Wigvilhba Wakas (Hereditary Chief Harvey Humchitt) remembers the day 110,000 litres of diesel and other pollutants spilled into Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) waters as if it was yesterday.

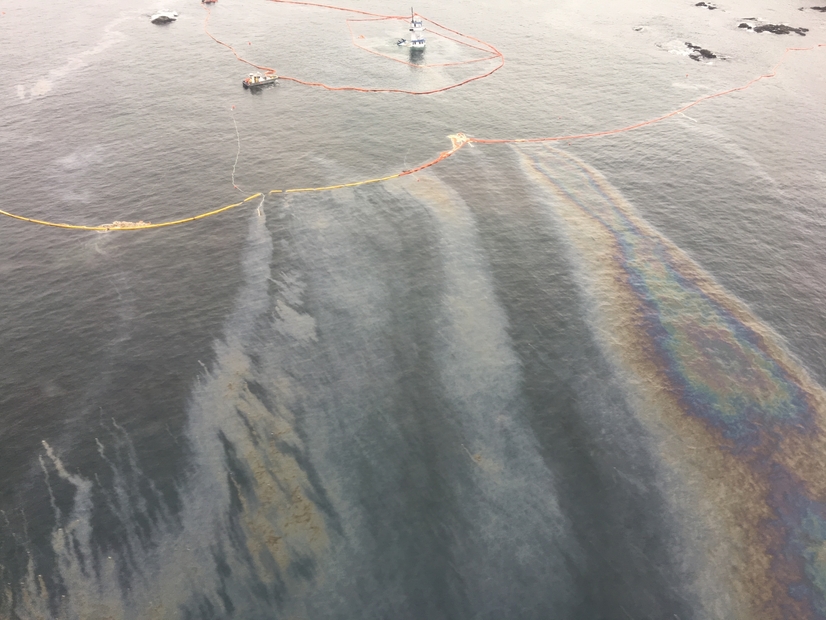

“It looked like a big herring spawn just penetrated the Seaforth Channel,” he said, recalling the stain that seeped into the water, streaking and discolouring the waves of the channel on the central coast of B.C. “The smell — the smell was so strong.” The spill occurred after a tugboat pushing an empty barge ran aground, breaching its fuel tanks on the rocks. It eventually sank.

“You could see the stern going down, down, down. The grinding noise it was making, it’s still so clear and vivid. The grey-blue sky — it’s so clear. If I was an artist, I’d paint a picture.”

The Nathan E. Stewart spill, on Oct. 13, 2016, left a lasting mark on the community based in Bella Bella, B.C. The Haíɫzaqv once regularly harvested at Gale Creek, close to the ancient village site Q́vúqvái in the territory of the Q́vúqvaýáitx̌v tribe.

But since the spill, Humchitt said they’ve been unable to harvest from the polluted waters that once brought them an abundance of foods such as c̓ikva (clam), k̓ínáxv (crab), p̓uái (halibut) and náłm̩ (ling cod).

“The impacts were felt right away. The community felt like … it was like losing a loved one,” Humchitt said.

But Canada’s Marine Liability Act doesn’t recognize cultural losses, which can include adverse impacts on harvesting as well as other social and ceremonial activities in an area affected by a spill. And as for economic losses, the nation has been tied up in litigation since 2018 seeking compensation for the long-term impact on their commercial clam harvest, almost all of which was from Gale Creek.

That’s why Humchitt and a group of Haíɫzaqv elected and hereditary leaders are in London, England, hosting an event to call on the International Maritime Organization to recognize cultural losses in its conventions.

“It seems unreal. I never thought I would have to go out of the country to address some of the concerns that we have,” Humchitt said. “But if that’s what it takes, then by all means.”

Established by the United Nations in 1958, the International Maritime Organization is the agency responsible for regulating the international shipping practices of 176 member states, including Canada. Its mission is to improve safety and reduce pollution from shipping, but also to determine compensation for harms when they occur.

Haíɫzaqv Chief Councillor K̓áwáziɫ (Marilyn Slett) said the delegation leaders hope calling for change will impact the maritime conventions that inform law in Canada and around the globe. They are playing the long game, hoping their advocacy in this forum can lead to change first at the International Maritime Organization, and then to Canada’s Marine Liability Act.

“The focus is raising awareness on the international stage about the need for international marine laws to recognize and provide redress for Indigenous cultural losses,” Slett said in an interview.

The delegation is attending the marine environment protection committee session this week with the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the only Indigenous body with formal standing in the International Maritime Organization. The session will tackle issues like greenhouse gas emissions, marine litter and underwater noise reduction. Transport Canada will also have a delegation at the session, and Canada has a permanent representative to the organization who will be in attendance.

“We know that it’s definitely not going to change overnight, but it felt really important for us to begin the conversation for global change,” Slett said.

The Inuit Circumpolar Council told The Narwhal that it holds a “significant role for all Indigenous Peoples” at the International Maritime Organization, saying, “We can’t and don’t want to do this alone.”

“Marine spills are one of the most significant and consequential impacts from shipping in our Arctic region. The impacts can be devastating to our livelihoods, way of life, transmission of Indigenous Knowledge, food security and current and future well being,” the council said in an emailed statement. “Everything possible must be done to reduce risks and invest in spill response.”

The International Maritime Organization told The Narwhal that one-third of the parties to the liability treaties would have to request a conference to amend the treaties, and any changes would also require affirmation from a majority of the parties.

The day of the spill, Humchitt recalls feeling helpless. The Nathan E. Stewart ran aground and knocked against the rocks for hours before it finally ruptured. The community waited 17 hours for oil spill responders from Transport Canada, as they watched the spill spread in the water. When help finally arrived, the diesel was difficult to contain.

“It could have been avoided. But that didn’t happen,” Humchitt said. The next day, he joined a flyover to view the expanse of the spill. “I never felt so bad,” he said.

Slett said her brother went out on the water that morning, like Humchitt did, and called her when he got back. “I’ve never heard my brother sound so distraught,” she said.

Slett said the area needs more rehabilitation, and the community hasn’t been able to make use of it the same way since the spill.

“[Gale Creek] was described as a breadbasket for our community,” she said. “We’re a marine community and we depend on a healthy ecosystem and a healthy ocean for our sustenance.”

Working with the federal government has been slow-going, she said, and they want to push the country to improve speed and efficiency of spill response, empower First Nations to respond to marine incidents and recognize cultural losses the same way it recognizes commercial and economic impacts.

Humchitt wants better practices to be in place before another spill. He points out that just a year after the Nathan E. Stewart spill, a barge loaded with millions of litres of gas and diesel broke loose from its tugboat and spent the night out of control before it was recovered. Sheer luck prevented an environmental disaster. But a spill like that would be catastrophic for the entire province, he said.

“We’re not only looking to make things right for ourselves to protect our shorelines,” he said. “It’s only a matter of time before another incident.”

In November 2016, about a month after the spill, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the government’s ocean protection plan. Transport Canada reports they have invested $2 billion in the plan so far, in initiatives such as expanding liability assurance, increasing funding for the Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary, and developing a strategy to long-term recovery from spills.

There’s a liability cap on how much can be applied to the polluter, and if the costs of the spill are more than that maximum amount, then additional compensation can be paid through an international oil pollution fund and a Canadian ship-source oil pollution fund.

But that liability cap doesn’t include cultural losses for Indigenous Peoples. As well, Canada and B.C. left it up to Kirby Offshore Marine Corp., the Texas-based company responsible for the Nathan E. Stewart, to conduct and pay for an environmental impact assessment, but the company has not completed one. (The company told The Narwhal it could not provide a statement due to the ongoing litigation). Over the years, the Heiltsuk Nation has been fundraising to complete its own environmental impact assessment of the long-term damage to the health of the ecosystem.

In its lawsuit, the Heiltsuk Nation is seeking damages from Kirby related to environmental impact assessments, losses of commercial and personal harvest, cultural losses, interference with Aboriginal Rights and legal costs. The nation says the fact no assessment has been completed prevents it from being able to fully quantify its losses.

Slett said Heiltsuk has requested that Canada come to the negotiating table to resolve the litigation, with actions like federal support for monitoring, assessment and restoration. “If Canada is serious about its commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Canada must show leadership by sitting down with us to recognize Heiltsuk’s cultural losses from the [Nathan E. Stewart] spill, rather than continuing court battles,” she said in a statement from London.

The nation is seeking to create an Indigenous Marine Response Centre. In 2021, it signed a memorandum of understanding with the Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada to move towards that goal, which Slett said is still underway. The federal department has been working with the nation to develop the Heiltsuk marine emergency response team, and in 2023 announced a pilot to train community members and integrate the team as a third-party responder within the federal response system.

Transport Canada was not able to respond in time to comment. During a 2020-2021 review of the Marine Liability Act, the department asked Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities about “non-economic losses” and heard that access to harvesting after an oil spill was a top concern for Indigenous communities.

The resulting report by Transport Canada acknowledged these losses are not included in the act, but concluded, “Compensation is currently available to address many of the concerns we heard about,” including for impacts on cultural activities. The department announced their intention to amend the act, and did so in 2023. Among other changes, the act was updated to increase liability caps and to recognize Indigenous Rights under Section 35 of the constitution — but very specifically to do with “pure economic loss,” not the non-economic losses communities had cited.

In 2019, the federal government fined Kirby over $2.9 million in penalties for the spill, which was caused due to a crew member falling asleep.

However, the Heiltsuk Nation has yet to receive compensation. In 2018, the nation filed a civil action against Kirby, the province and Attorney General of Canada, which was split into two separate cases that are ongoing. One case is focused on liabilities from the company while the other grapples with issues of Indigenous Title and Canada’s duty to consult with Heiltsuk to allow oil to be transported through the territory.

Indigenous Title to marine areas is murky in Canadian law. Despite the fact Canada has the longest coastline of any country in the world, and First Nations have always used those coastlines, there is “ongoing legal uncertainty associated with Aboriginal title to waters and submerged lands,” Kate Gunn and Nico McKay, two lawyers at First Peoples Law, wrote in a 2023 editorial about The Nuchatlaht v British Columbia. Gunn and McKay argue that coastal Indigenous Peoples are prevented from exercising their full constitutional protections over their entire territories, compared to Indigenous Peoples on mostly dry land.

Of course, Indigenous Title to marine areas is clear in Indigenous legal systems like Heiltsuk Ǧviḷás (laws). But Canada has a “prove it” approach to Indigenous Title, lawyers Gavin Smith and Eugene Kung explained in a Policy Options editorial, which creates an expensive and onerous barrier to justice for First Nations. But, Smith and Kung write, “Aboriginal Title and governance exist and apply in Canadian law now, even if the bounds of title lands have not been delineated in a court case.”

The Heiltsuk leaders hope their trip to the International Maritime Organization will hold Canada to account, but also help people understand their connection to the water and the deep grief they have experienced. Humchitt wants to bring awareness to those in power, and show them how his people are impacted by Canada’s laws and recognition.

“I’m thinking about our grandchildren or great-grandchildren. What will they have if we don’t stand up to protect ourselves and make changes to the rules that are made by others? They are impacted directly. We are impacted directly. And that hurts sometimes.”

Updated on March 26 at 10:30 a.m. PT: This story has been updated with a correction to the process of amending liabilities treaties at the International Marine Organization. Changes require affirmation from a majority of parties, and not one-third as originally written.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...