Why Ontario is experiencing more floods — and what we can do about it

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...

Don and Marg Wieben have lived side-by-side with the oilpatch for 45 years.

“We accepted it at the time as part of our public responsibility,” Don explains from his kitchen table when photographer Amber Bracken and I visited their family home near Fairview, Alta.

“Like if you had a new highway go through, some people were going to have to give up land for the good of the community.”

Don Wieben talks about the pipelines crisscrossing his family’s farmland at home near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The location of pipelines crossing under the Wiebens’ fields is often obvious because of crop degradation. Those pipelines are likely to remain there forever, and there is no timeframe on when companies need to obtain reclamation certificates. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

That commitment to what they felt was the public interest came with some downsides — like the spills.

There was the time their daughter-in-law, Bev Wieben, found herself getting headaches from a strange smell in the air. She went out for a walk and found the source of the fumes was a pipeline break. Then there was the time Marg was out checking the cattle, and found another break. And the gas they saw bubbling up at the surface.

Bev Wieben stops to visit her cattle near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

And there have been what Don considers to be the small inconveniences. Sinkholes, where pipelines have been buried, that the farm equipment gets stuck in. The noise. The traffic.

“You can’t say it was all bad though,” Don says. “There were positives to it.”

As part of the arrangement, the family received annual payments for wells drilled on their property, and one-time payments when companies wanted to obtain a right-of-way to put a pipeline under the family’s land.

Don and Marg Wieben look out over the Peace River from their family’s land near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Little did they understand at the time, as they signed agreements with a landman who made regular trips to their kitchen table to broker deals, that those pipelines — and the company access to their land — could last “in perpetuity.”

That means the numerous pipelines buried under their land will likely remain there forever.

“It’s junk,” Don says of the pipelines left behind. “It’s garbage. It’s like going on a picnic and leaving all your trash in the bush.”

Don Wieben surveys the family land near Fairview, Alta. “We had a real nice quiet corner of the world down here,” Don said. “The oil patch changed that somewhat.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

According to Natural Resources Canada, there are 840,000 kilometres of pipelines of various types buried in the ground across the country.

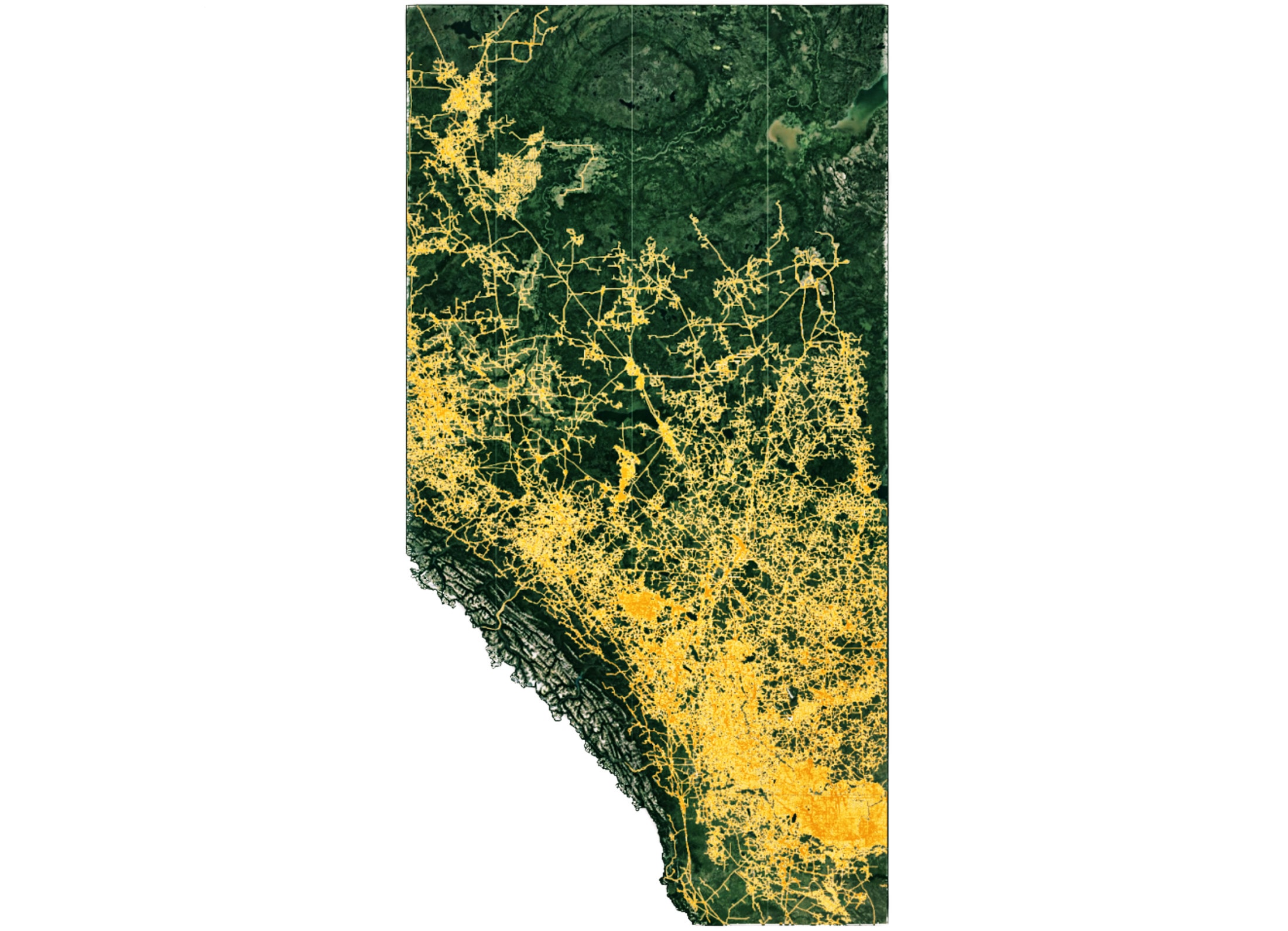

In Alberta alone, there are more than 400,000 kilometres of oil and gas pipelines weaving under the surface of the province — a distance, as the Alberta Energy Regulator points out, greater than between the earth and the moon. The majority of those pipelines, nearly 60 per cent, carry natural gas.

Seldom are those pipelines certified as reclaimed, the process that marks the completion of environmental cleanup.

Alberta’s pipeline network as of 2016. According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, there are over 400,000 kilometres of pipelines criss-crossing under the province. Map: Brad Stelfox, Landscape Ecologist

Oil and gas infrastructure on the Wieben family land in Fairview, Alta. Farmers are provided annual compensation for well pads on their land, but are granted just one-time payments for pipelines installed under their fields. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Sharon J. Riley interviews Don Wieben and his daughter-in-law Bev on their land near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A search of the Alberta Energy Regulator’s website revealed 807 reclamation certificates related to pipelines, dating back to 2014.

Meanwhile, the regulator reports having approved approximately 12,000 new pipeline applications in 2018 alone.

The 807 reclamation certificates refer only to pipelines listed as part of a certificate for other facilities. Shawn Roth, a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator, told The Narwhal by email that there are more reclamation certificates that have been issued for pipelines alone, but that he could not say how many. “Due to ongoing data verification efforts, we are unable to provide that information,” Roth wrote.

Because of this, he added, any information about pipeline reclamation from prior to July 2018 is “subject to change.”

The regulator has, however, frequently advertised the numbers of new pipeline licences it issues.

A video produced by the regulator to introduce its online system, OneStop, boasted that automation of approvals enabled “25,000 pipeline applications processed annually — automatically.”

A company installing a pipeline has no legislated obligation to remove the pipeline, or to reclaim — the process of returning the land to an equivalent state — within any designated time frame.

An abandoned pipeline on the Wieben family land in Fairview, Alta. In Alberta, there are no timelines when an abandoned pipeline needs to be reclaimed. Photo Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

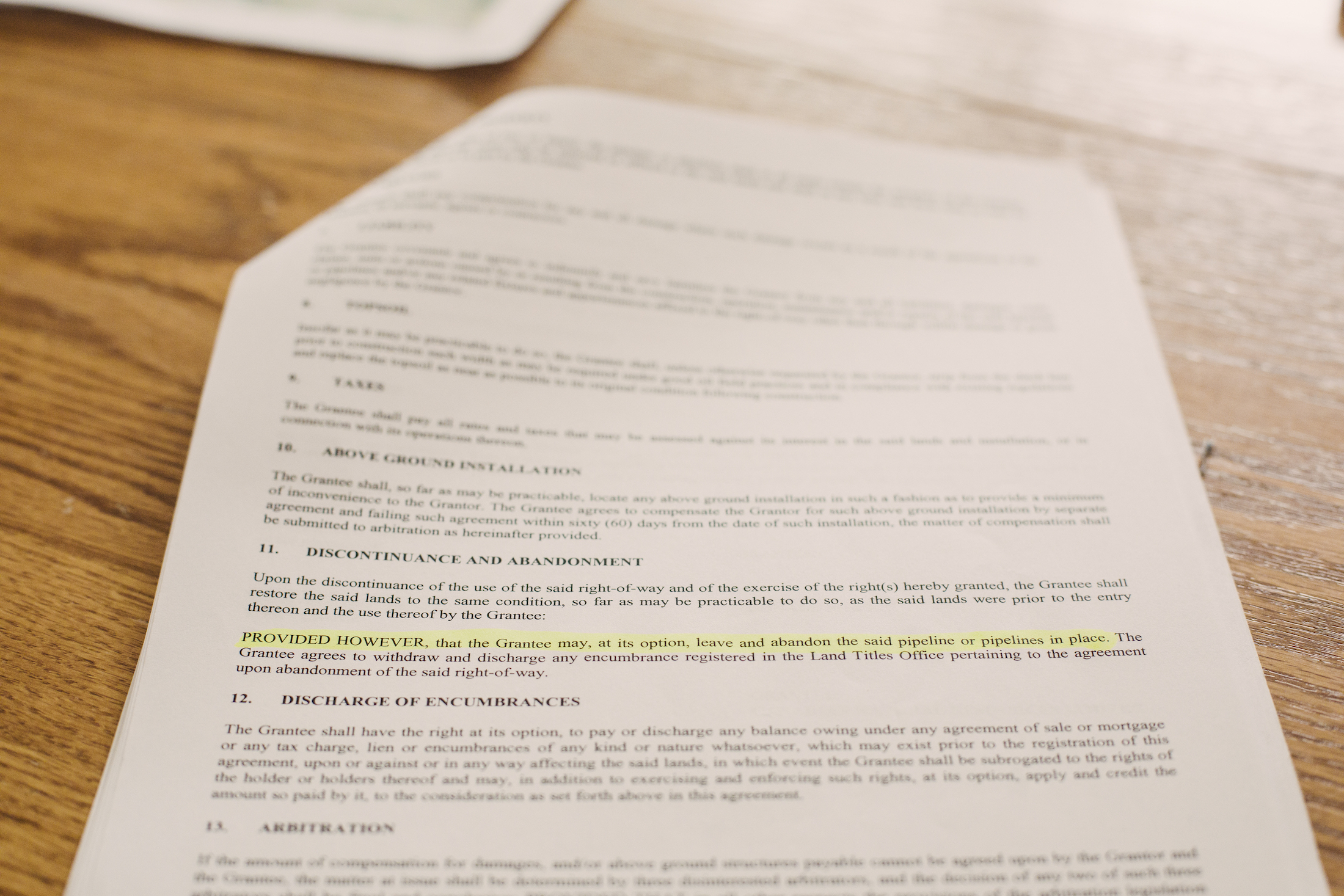

Contracts, like the one the Wiebens signed, specify that companies “shall restore the said lands to the same condition, so far as may be practical to do so, as the said lands were prior [to the pipeline’s installation],” — but include no time frame for when that needs to be done.

Landowners are typically granted a one-time payment when a pipeline is first constructed, but do not typically receive annual compensation like they would for oil and gas wells.

And once the pipeline is there, it will likely remain there forever.

Contracts include a clause about never removing the pipeline — “provided however that the grantee may, at its option, leave and abandon the said pipeline or pipelines in place.”

Signs denoting the presence of multiple gas pipelines on the Wieben farmland near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The Farmers’ Advocate Office of the Government of Alberta makes it clear: “The default is for the pipeline to remain in the ground.”

“When a pipeline is abandoned, it is permanently deactivated and it is not intended to allow possible future use. A pipeline can remain … indefinitely.”

Don is concerned about this, and also that the company can retain the right-of-way on the land, meaning that the land needs to remain clear of buildings and faces other restrictions — restrictions he says are also unfair to pass along to future generations.

The Wiebens first moved to the Peace Country in northwestern Alberta in the early 1970s. They had fallen in love with the landscape: the huge, active skies, the snaking Peace River in the valley beside their farmland, the black bears feeding on saskatoon berries alongside their fields, the pairs of deer ears just visible in crops of canola.

A view of the Peace River from the Wieben family’s land near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

When Don, now retired at 76, used to go out to check the cattle in the night during spring calving season — around February — he remembers looking up at the sky and being awed by the vastness. On clear nights, he’d lie down in the snow and watch the colours of the northern lights dancing above him.

Don and Marg moved to Alberta from Ontario, in pursuit of a life in farming. “We didn’t know the difference between a steer and a heifer,” Marg jokes now. They took on a big mortgage to buy 10 quarters of land and move to a place they’d never been, along with their four kids.

The Wieben family farm near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The land was beautiful, they thought, “an awful nice part of the world,” Don says, though it came peppered with a few gas wells and small pipelines to connect them. The Dunvegan gas field was just getting started. Together, their family now owns about 40 quarters of farmland in the area.

“We can’t say that the revenue from the wells and pipelines was not helpful,” Don says. “It certainly was.” Without it, their mortgage may have been impossible.

Looking back, though, that money came with downsides.

“We had a real nice quiet corner of the world down here,” Don says. “The oil patch changed that somewhat.”

Don Wieben stands next to canola that is close to oil and gas infrastructure — noticeably shorter than chest-height crops elsewhere on the farm — near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Marg Wieben, Don Wieben, Greg Wieben and Bev Wieben gather next to oil and gas infrastructure in the middle of a canola field on their property near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Farmers have experienced myriad concerns when it comes to crops grown above pipelines.

Some farmers report that the friction of a substance moving through the pipes causes soil to warm up, meaning snow melts more quickly over pipelines, findings that have been supported by research in other parts of the world. That can make crops mature sooner in the warmer soil — so when it comes time to harvest, crops above pipelines are over-ripe.

Tom Baumann, an associate professor of agriculture at the University of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia, who is himself a farmer living with pipelines, has studied the effects of pipelines on crops. He says the effects are obvious.

“All of the sudden, when you’re harvesting, you encounter a part of the crop that’s overripe — because there’s been heat.”

The presence of pipelines can be clearly seen from above farmers’ fields near Fairview, Alta, where crops are markedly less productive when growing in soil disturbed by a pipeline. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Bev Wieben and her father-in-law Don Wieben survey their farmland, and the pipelines criss-crossing it. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Baumann is a member of the Collaborative Group of Landowners Affected by Pipelines — a group of farmers who describe themselves as not anti-pipeline, but who seek to be “full partners” in planning for development and lessening damage to valuable crops.

“That’s a major thing for us,” Baumann told The Narwhal.

Back in the 1980s, Agriculture Canada put out a report called “Impacts of installation of an oil pipeline on the productivity of Ontario cropland.”

The study found that crop yields were reduced by 50 per cent in the years following the installation of a pipeline, and the effects on crop productivity continued to be felt for years.

There are other potential impacts as well — a 2014 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health noted “early warning signals about soil heavy metal pollution” that can occur in farmers’ fields when pipelines are constructed.

But most often, concerns about farming over pipelines are often linked to issues with soil. Soil that has been dug up to install a pipeline is likely to be more compacted than surrounding areas, and therefore less conducive to healthy crops. A 2015 study in the journal Soil Use and Management noted “severe compaction of the subsoil can be caused during the installation of pipelines.”

Baumann said that careful removal of different layers of soil during pipeline installation — for reuse once the pipe is in the ground — can help mitigate effects on crops, and that putting “public pressure” on companies has helped him and other members of the Collaborative Group of Landowners Affected by Pipelines lessen the impacts on their crops.

But the impacts on soil from installing the pipeline can go on for years — impacts that Baumann said are starkly visible in crops. “You can see the difference because of the disturbed soil — and that goes on for thousands of years.”

“For half a century, it’s been lessening the yields of farmers across the country.”

Don, Marg and Bev Wieben out for a drive around their family land near Fairview, Alta. Photo Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Baumann is also concerned about leaks. Once pipelines are no longer in use, they’re supposed to be washed and plugged — known in the industry as abandoning. But Baumann said he’s “absolutely still concerned” about leaks, even after pipes have been plugged.

“There’s still residue,” he said. And, he added, that residue can leak into soil, especially as pipes age.

Whether in ten years or 100 years, he said, the pipe “will eventually deteriorate.”

Of the more than 400 pipeline “incidents” reported in Alberta last year, roughly three quarters were the result of leaks or ruptures.

A shut-in well on the Wieben family land near Fairview, Alta. Shut-in wells may one day be reactivated. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Bev and Marg Wieben look over oil infrastructure on the family land. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Bev and Greg Wieben look over a field on their property, which is heavily trafficked by pipelines just beneath the surface near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A video put out by the regulator notes that the top cause of incidents is internal corrosion, representing 38 per cent of reported incidents.

As a result of those pipeline incidents reported to the Alberta Energy Regulator, approximately 3.5 million litres of substances were released, the majority of which was “non-fresh water.” Non-fresh water can include highly saline water, which can be damaging to crops, natural vegetation and wetlands.

Don is frustrated by leaks from faulty or aging pipes. “We as landowners should not bear the responsibility of the oil patch being sloppy in not putting in pipelines that would last long enough to do the job,” he told The Narwhal.

The Farmers’ Advocate Office notes that the regulator “generally does not recommend [pipe]line removal because it can cause an unnecessary and significant disturbance to soils and the environment.”

That leaves a complicated conundrum — dig up the land again to remove the pipe, further disturbing the soil, or leave the pipe there forever?

The Farmers’ Advocate Office defines an abandoned pipeline as one that has been disconnected from operating facilities. Its open ends must be plugged or capped. The line must be cleaned, purged of any remaining oil or gas and “left in a safe condition.”

“To say that a pipeline isn’t going to hurt anything in the ground, that’s just not the case. … It’s a hidden danger, period,” Don says. “It’s the things you can’t see that are wrong.”

The Farmers’ Advocate Office in the Government of Alberta echoes that sentiment in a publication called “Pipelines in Alberta: What landowners need to know.”

The document encourages farmers to act as if any pipeline buried in the ground could be potentially dangerous, whether or not the company says it has been safely discontinued.

“To maintain safety, [farmers] should always treat a pipeline as if it is operating.”

The Farmers’ Advocate Office did not respond to The Narwhal’s requests for comment on landowner concerns with pipelines.

Shawn Roth, spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator, wrote by email that “pipelines that are no longer needed are often left in the ground to ensure the land and soil are not disrupted further.”

“However, the [regulator] requires pipelines that are no longer needed to be taken out of service safely following the Pipeline Rules. This includes ensuring they are emptied, purged, isolated and left in a safe condition so there are no risks to the public or environment.”

Contracts landowners are asked to sign by energy companies make it clear that pipelines can remain in the ground indefinitely. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Don is adamant that potentially leaving behind a network of hundreds of thousands of kilometres of abandoned pipelines buried under the province is not the legacy he wants for his generation, nor does he want to pass along the headaches that can come along with them, like the limited farming activities one can do on the land over a pipeline right of way — or the sinkholes.

Farmers and landowners have long complained about sinkholes appearing on their land after pipelines are installed, from Alberta to Texas to Pennsylvania. In extreme cases, sinkholes may be large enough to stand in, in others, the disturbed soil may simply settle, leaving a depression where water can pool — and tractors can get stuck.

Don is adamant that with modern technology, companies should be able to pull out the pipe and restore the landscape.

“We don’t think our generation should leave junk pipe scattered over all our land for the next generation to deal with,” Don says. “I don’t think that’s correct and I don’t think that’s fair.”

Don Wieben shows a successful part of the family’s crop near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

This area of the crop is unaffected by the presence of pipelines or wells: Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Knowing what they know now, Marg is regretful there’s oil and gas infrastructure on their family farm.

“I would have this back to its pristine state,” Marg says. “No wells, and no money coming in, if I could.”

Not that she necessarily had a choice.

Many landowners have few options but to agree to a company wanting to build a pipeline under their land.

Marg Wieben looks over oil and gas infrastructure on the family land in Fairview, Alta. Marg “would have this back to its pristine state,” if she could, she told The Narwhal. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Landowners can try to put up a fight when a company proposes a pipeline under their land, and may have success in having it rerouted, but the company can also go to Alberta’s Surface Rights Board, a quasi-judicial tribunal, to obtain a right-of-entry order.

Don’s not so sure whether he regrets having oil and gas on their property altogether, but he is very concerned about what’s going to happen to all the pipelines left to rust in the ground — and who will pay if and when they do ever need to be removed. He wants government and companies to take action to ensure oil and gas infrastructure is truly cleaned up.

“Marg and I’s generation lived in an awful good period of time,” he says.

“It shouldn’t be some generation behind us that has to pick up the tab for taking this out.”

Don Wieben in front of oil and gas infrastructure on the family’s property near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The Wieben family home near Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

When we visit, Don takes us on a tour of his family’s land — we drive from well to well, through access roads cut through fields of canola as tall as his chest.

He stops to check crops, point out birds and deer and to look at the signs marking the numerous pipelines cutting under the fields.

On our second day in Fairview, he offers to take us for a flight in a Cessna 172, a small four-seater plane owned by his family members. An aerial view, he says, will give us a better idea of the Peace River region, and let us really see the lay of the land.

Above the Wieben family farm in the family’s small Cessna. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Wieben family farm. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

It’s thunderstorm season and thick, black clouds gather on the horizon as the sun rises early in the morning when we take off in the Cessna. We fly up above the town of Fairview and the meandering Peace River, cut deep into surrounding fields.

Eventually, the Wieben farm comes into view, and we see everything we saw on our driving tour the day before, this time in miniature — tiny buildings and wells scattered across a vast landscape, under an even vaster sky.

Journalist Sharon J. Riley in the Wieben family Cessna above Fairview, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Pipelines can be seen where crops are less productive. Photo Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

As we fly, Don is taken aback. Criss-crossing fields are clear lines — green and brown where canola should be in its blooming yellow splendour.

It’s undeniable where pipelines cross under a field, marked by the crystal-clear crop degradation.

Even Don is surprised. He didn’t think it would be quite so obvious.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...