Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A version of this article also appears on the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Policy Note. This is the second in a two-part series. Read the first part here.

BC Hydro was so worried that its Peace Canyon dam could be badly damaged if an earthquake was triggered at a nearby natural gas industry disposal well that it briefly considered buying the facility for $5 million to make the problem go away.

But the buyout idea was quickly rejected because of the precedent it would set. Virtually all the fossil fuel resources near the dam and for hundreds of miles in every direction had been sold by the provincial government to companies hungry to drill and frack for natural gas.

That placed the publicly owned hydro provider — and its sole shareholder, the provincial government — in a bind. What was to stop another company from drilling a similar well nearby? Would that well owner need to be compensated to eliminate the threat to the dam. And if so, who would foot the bill?

Details on the conundrum facing BC Hydro are contained in hundreds of pages of emails, letters, internal memos, and handwritten meeting notes obtained in response to a freedom of information (FOI) request.

The documents show that dam safety officials and engineers at BC Hydro knew for 40 years that the Peace Canyon dam was built on top of layers of weak shale rock that could shear or break far more easily than previously thought. They also knew the dam was at risk of significant damage and potential failure in the face of earthquakes induced by the natural gas industry.

The documents show that BC Hydro officials became particularly concerned about the disposal well in early March 2017 after Scott Gilliss, the utility’s point person on dam safety in the Peace region, discovered that three to four tanker trucks at a time were delivering liquid waste to the well site. The well site was owned by Canada Energy Partners and was only 3.3 kilometres away from the dam.

Investigative reporter and award-winning author Andrew Nikiforuk reported the company “spent $3 million drilling, upgrading and operating the well and pumped about 16 million litres of waste water” down the wellbore in the first three months of 2017.

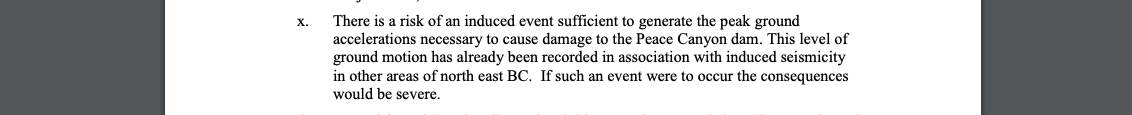

On March 14, 2017, Stephen Rigbey, BC Hydro’s director of dam safety, emailed the provincial Oil and Gas Commission, which had approved the well operation, warning that the Peace Canyon dam had “foundational problems” and that even a magnitude 4 to 4.5 earthquake could cause damage to the structure.

The commission called Rigbey’s revelations a matter of “high concern.”

Two days later, the commission’s vice-president of compliance, Lance Ollenberger, formally notified the disposal company’s CEO, Benjamin Jones, that he had suspended the disposal permit.

Ollenberger told Jones there was a chance an earthquake triggered at the well site could cause ground motions that were stronger than the dam could withstand. He went on to note that ground motions as strong or stronger had already been caused at other natural gas industry operations in the province.

“If such an event were to occur [near Peace Canyon dam] the consequences would be severe,” Ollenberger said.

A message from B.C. Oil and Gas Commission’s vice-president of compliance, Lance Ollenberger, to the CEO of Canada Energy Partners, warning about the severe consequence of a fracking-induced earthquake near the Peace Canyon dam.

But if BC Hydro thought that was the end of the matter, it was mistaken.

Two weeks later, Jones formally appealed to the Oil and Gas Appeal Board, a body that typically adjudicates disputes between landowners (usually farmers) and the commission.

Jones told the board the permit cancelation was not justified because there had been no earthquakes generated at either the disposal well or the nearby dam.

He also warned that if the decision to cancel the permit was not overturned he would seek financial compensation — either $5 million in cash split between the commission and BC Hydro, or “$625,000 cash plus a transferable royalty credit of $2.34 million” from the commission and “$625,000 cash plus a transferable electricity credit of $2.34 million from BC Hydro.”

But the appeal board was unmoved.

While the board concluded there was “a low likelihood” the disposal well could induce an earthquake strong enough to “destabilize” the Peace Canyon dam, such a horrific outcome could not be dismissed.

Disposal wells and fracking operations “increase the likelihood” of earthquakes, the board said, siding with the commission’s original decision to cancel the permit.

The ruling gave the commission all the justification it needed to shut the well down for good.

But much to BC Hydro’s dismay, the commission did not do that.

Instead, on Dec. 4, 2017, the commission told the company it could potentially resume disposal operations again — just so long as numerous conditions were met.

The conditions included: installing new equipment to record seismic events within five kilometres of the well site; installing other equipment to record the ground motions associated with nearby earthquakes; and reporting the “date, time, location, magnitude, ground acceleration and depth” of any localized earthquakes in regular, one-month intervals to the commission.

That decision, according to the FOI documents, meant that BC Hydro was rapidly running out of options to protect the dam from the disposal well or any other encroaching oil and gas industry operations for that matter.

In an email to six BC Hydro colleagues on Dec. 22, Rigbey said it would be “much easier said than done” to get the disposal well permit permanently cancelled:

“We only have a few options.

Make another appeal to the OGC tribunal (destined to fail), followed by

Initiate a court challenge, outside of the OGC tribunal (ie a crown corporation taking its sole shareholder to court!)

Buying out the well (already been discussed, with an asking price of $5M), and then being saddled as a well owner with all responsibilities for well closure and all the ongoing residual risks, as well as making a precedent that BCH [BC Hydro] will buy out anyone who gets a legal permit to drill a well…

We cannot come up with any other alternatives, other than ensuring we have strict protocols in place,” Rigbey wrote.

The buyout option’s $5-million price tag was particularly noteworthy because it signalled that BC Hydro knew that it was effectively on the hook for the entire cost that Jones had said he would seek on a cost-shared basis from both the commission and BC Hydro earlier.

By offering Canada Energy Partners a “conditional” way forward, the commission could not be accused of taking away or expropriating the company’s “subsurface rights,” and thereby side-step any question of having to compensate the company for those lost rights.

BC Hydro first became aware of disturbing ground motions or tremors at its Peace Canyon dam in 2007. Coincidentally, that turned out to also be a momentous year for the oil and gas industry and its biggest booster, the B.C. government.

Provincial statistics show that fossil fuel companies paid the provincial government a record $1.2 billion in 2007 for the rights to drill and frack for natural gas and oil in northeast B.C. It was the beginning of an unprecedented four years of so-called “land sales,” that would see more than $5.3 billion channeled into the provincial treasury.

Between 2007 and 2010, fossil fuel companies gained rights to drill and frack for natural gas under an additional 2 million hectares of land in northeast B.C. — an area larger than 5,000 Stanley Parks.

Fracking pad in northeast B.C. near Farmington. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

What drove the unprecedented spike in land sales was the realization that fracking (pressure-pumping vast amounts of water, sand and chemicals) into shale rock formations deep below the ground could liberate immense quantities of natural gas and oil.

Even the provincial government, which had encouraged a bidding war between companies anxious to exploit those resources, was taken aback at the sharp climb in sales prices during that time.

In a financial review released in September 2009, the provincial finance ministry noted:

“At $3,710/hectare, the average bid price was $3,000 higher than assumed and 99 per cent higher than 2007/08 indicating industry’s continued interest in exploring and developing B.C. resources — especially deep and shale natural gas reserves.”

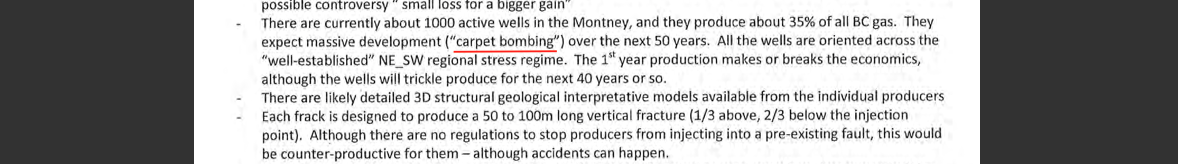

All that sales activity signalled that fracking was poised to explode in northeast B.C. This included shale rock formations that extended under or near the Peace Canyon and WAC Bennett dams, as well as the planned Site C dam — BC Hydro’s third hydroelectric dam on the Peace river. Today the dam is under construction about 70 kilometres as the crow flies downstream from Peace Canyon.

The government’s fire sale of subsurface rights had brought fracking to the doorstep of some of the most critical — and potentially vulnerable — hydroelectric dams in the province. In an email sent to several of his BC Hydro colleagues in April 2012, Rigbey warned that what lay ahead was akin to “carpet bombing.” And he hazarded a guess that the bombing campaign might last 50 years.

Email from Stephen Rigby

In BC Hydro’s eyes, the disposal well near the Peace Canyon dam was something of a well from hell — a facility troublingly close to a dam that was both situated on top of weak shale rock and known to be near existing faults that could be reactivated during an earthquake.

Another well site that might fit that bill for BC Hydro is a massive “multi-well” natural gas pad situated just 20 kilometres south of Site C.

The roughly eight-hectare well pad was carved out of farmland by Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. on a bench of land between the Peace and Kistkatinaw rivers.

On Nov. 29, 2018, the company was in the process of fracking its eighth and ninth gas wells on the pad when it touched off the second-largest earthquake yet caused by a natural gas industry fracking operation in the province.

Author Ben Parfitt at the CNRL gas well where a 4.5 magnitude earthquake was triggered in November 2018, resulting in a “strong jolt” at the Site C dam construction site. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

According to the FOI documents, the 4.5 magnitude earthquake caused a “strong jolt” at the Site C dam site. All construction work was immediately suspended and workers evacuated from the site.

The commission quickly identified the fracking operation as the cause of the earthquake and the company immediately suspended its operations. The commission then alerted the public that fracking operations would remain suspended at the site and would not be allowed to resume unless the commission explicitly gave its written consent.

Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., or CNRL, is just one of many companies operating in an area the commission has dubbed the “Kiskatinaw seismic monitoring and mitigation area.” The area consists of expansive grain fields and wooded areas between Dawson Creek in the south and Fort St. John and the Site C dam to the north. The rural enclave of Farmington has been particularly affected by developments in the zone.

The commission put new rules in place in the area in May 2018, recognizing that increased gas-drilling and fracking in the Farmington area was causing earthquakes.

The new rules included a requirement that industrial activity be immediately suspended if either a company or the commission concluded that a magnitude 3 earthquake or greater had been triggered by a fracking operation.

Other rules required companies to “take action” and have “mitigation plans” in place should earthquakes of magnitude 2 or greater be triggered by fracking. And, if any earthquakes of 1.5 magnitude or greater were triggered during fracking, companies were required to report such tremors to the commission within a day of them occurring.

But as the events of Nov. 29, 2018 underscored spectacularly, the new rules failed to prevent an earthquake strong enough to be felt in households throughout the region and in communities 100 kilometres apart.

Fracked gas development in northeast B.C. near Farmington. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Significantly, that earthquake is nowhere near the strongest to date to be associated with natural gas industry operations worldwide.

A 5.7 magnitude earthquake in Oklahoma in 2011, later linked to a disposal well operation, released 53 times the energy of the Nov. 29 event. The earthquake is considered the most powerful yet to be triggered by a fossil fuel industry operation. It was felt in at least 17 U.S. states, buckled a local highway in three places and caused injuries. More recently, a 4.9 magnitude earthquake in China’s Sichuan province was suspected of being triggered by fracking. Two people were killed by the tremors and county officials ordered the suspension of the fracking operation.

In early June of this year, the commission received an independent analysis of the Kiskatinaw area, done by two geoscientists with Enlighten Geoscience Ltd.

The scientists noted that much of the rock formations underlying the Kiskatinaw region were riddled with faults, and that it would take only small increases in the pressure at which fracking operators pushed water, sand and chemicals underground to cause those stressed faults to slip.

“Only small fluid pressure increases are sufficient to cause specific sets of fractures and faults to become critically stressed,” the report’s authors, Amy Fox and Neil Watson, warned.

The report gave the commission plenty of ammunition should it wish to extend the suspension of CNRL’s fracking operations at the well site indefinitely or to make the suspension permanent. But a little more than four months after receiving the report, in a move eerily similar to its earlier about-face at the disposal well near Peace Canyon, the commission decided to lift the suspension order and allow CNRL “to resume operations.”

A map showing oil and gas leases surrounding the location of the Site C dam, currently under construction.

Site C dam construction on the banks of the Peace River in the summer of 2018. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Under new permit conditions — which included “a lower threshold” provision — the company had to “take action” when an earthquake of magnitude 1.5 was triggered, versus the earlier threshold of magnitude 2. The company was also required to report to the commission any earthquakes of magnitude 1 or greater within 24 hours, versus the previous threshold of 1.5.

The commission’s decision to lift the suspension was issued in an “industry bulletin” that ran to less than one page. Nothing in the short document indicated how any of the amendments would actually reduce the likelihood of future earthquakes. The document also remained silent on the issue of what had prompted the commission to lift the ban.

Once again, the commission opted not to cancel a permit in its entirety — an action that almost certainly would have resulted in CNRL seeking financial compensation, along the lines of what Canada Energy Partners had threatened at its Peace Canyon disposal well operation.

Less than one month after the ground shook with force at Site C in November 2018, Terry Oswell, a dam safety engineer at BC Hydro, was on a phone call with eight commission personnel. The subject of the call was to discuss proposed fracking activities by Crew Energy, scheduled to take place near the Site C construction project in January 2019.

Details of what was discussed on the call that day are contained in a subsequent email sent by Oswell on Dec. 11 to two BC Hydro colleagues as well as at least two other individuals whose names are redacted from the FOI record.

The email noted the commission had “a shake map” for the earthquake that had been triggered just two weeks earlier by CNRL and that the commission “would share it” with BC Hydro. Oswell went on to say:

“The OGC has asked operators in the area to provide information on the type and length of faults in their areas. They said the event on Nov 29th was in the graben area [a reference to depressed area of the earth’s crust bordered by parallel faults] which may be conducive to larger events but that the … [area] where Crew is working may also have the same type of faulting.”

By then, BC Hydro also knew that there were numerous faults in close proximity to the Site C dam, including two parallel faults that pointed like fingers toward the dam site and that came very close to reaching it — faults that if reactivated, could have significant consequences in the event of a strong earthquake.

In the same email, Oswell recalled some of the questions commission personnel on the call asked. The questions indicated that commission personnel knew that a strong earthquake was at least a possibility, and that if it was strong enough, it could have significant implications for at least a portion of the workers at the Site C dam.

According to Oswell’s recollection of the call:

“Some of the questions the OGC asked:

Have we considered shutting down construction activity because of the work Crew is doing in the area? I think we clarified that they were talking about after they trigger a shake in which case we would follow the response plans and only if it was unsafe to resume work, would we not continue until it was made safe. And that we are not expecting the cofferdams to fail because of a fracking event but that it’s prudent to evacuate people until they are inspected.

How many people are working below the water level? Several hundred

What would we do if Crew caused a shake? Same response as per the 29th event and we would be asking the OGC for the information about the event.

How was the Nov 29th event felt on site? Initial jolt felt strongly and widely followed by several smaller shakes and then a final larger jolt felt widely.”

Less than a month after that December 2018 phone call, a letter arrived at the commission’s headquarters in Victoria’s inner harbour, which is only a short distance from the provincial Legislative buildings.

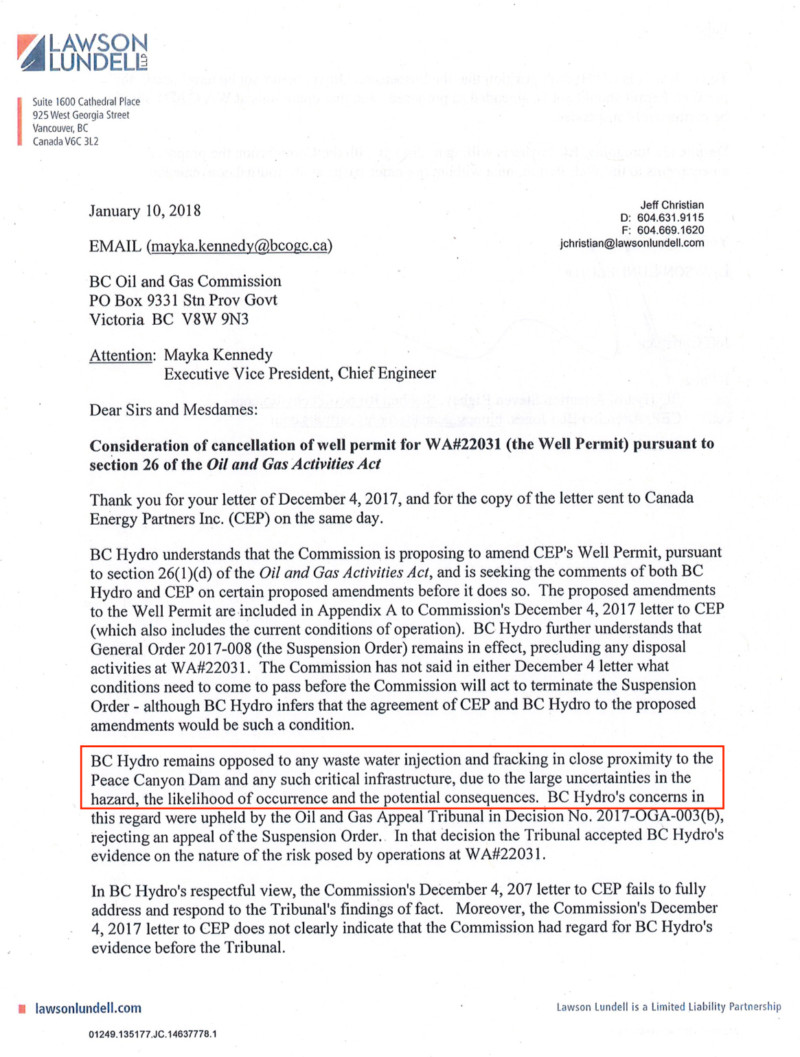

The letter was written by Jeff Christian, a seasoned lawyer who has represented BC Hydro on several high-profile files, and was written primarily to address BC Hydro’s opposition to any resumption of operations at the disposal well at Peace Canyon. But it applied equally to all of the Crown corporation’s Peace River dams.

A letter from lawyer Jeff Christian, stating BC Hydro’s opposition to fracking or waste water injection near the Peace Canyon dam.

“BC Hydro remains opposed to any waste water injection or fracking in close proximity to the Peace Canyon Dam and any such critical infrastructure, due to the large uncertainties in the hazard, the likelihood of occurrence and the potential consequences,” Christian said.

Christian’s letter reiterated what senior dam safety and engineering officials at BC Hydro have said for years: encroaching fracking operations pose significant risks to some of the Crown corporation’s most important dams. The most efficient way to control such risks, those officials have said repeatedly, is to eliminate the prospect for them happening at all, at least anywhere near such critical infrastructure.

But that is not happening.

In the place of restrictions on fracking industry operations in areas of high concern are modestly tougher but completely untested permit conditions that the provincial government has no way of knowing will prevent a future catastrophe.

As a report to the provincial government noted earlier this year, one of the great scientific unknowns with fracking is just how powerful an earthquake operations might trigger.

No amount of permit conditions attached to a fracking or disposal well permit gets around the fact that predicting when an induced earthquake may occur, where it will occur and how strong it will be is an impossibility — an unsettling conclusion that the provincial government has yet to act on.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...