Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Mount Stelfox rises some 8,600 feet above Bighorn Country — its peak overlooking the azure waters of Abraham Lake. The snow-dusted peaks of the Rockies form a fringe on the horizon.

The mountain was named after Harry Stelfox’s grandfather, the late Henry Stelfox Sr., in 1956.

Stelfox Sr. moved to the small town of Rocky Mountain House in the 1920s, starting up a livery stable on main street, and took an immediate interest in the local area, working on conservation projects — attempting to reintroduce beaver and bison, for example — for many years.

Last summer, grandson Harry Stelfox, now 70 years old, took three of his own grandkids up the peak. Stelfox is sure his grandfather would be proud that the peak could be protected in a wildland provincial park proposed for the region as part of the Alberta government’s Bighorn Country Proposal.

“[My grandfather] was a great lover of the land,” Stelfox said. “That interest influenced our whole family.”

Stelfox worked for more than two decades as a wildlife biologist with the provincial government — just one part of his connection to the outdoors. “I’m an avid hunter. I’ve hosted an annual family deer hunt for the past 36 years,” Stelfox told The Narwhal.

“We still have a wonderful environment out there,” Stelfox said of the region — his family still owns land adjacent to the area. “But it’s changed dramatically.”

Therein lies the issue in what has become an increasingly fraught battle over the future of the crown land that butts up against the eastern slopes of the Rockies. Plans for Bighorn Country are currently up for consideration in a new proposal from the provincial government.

In an already polarized political environment, the government’s plans — for a mixture of provincial parks, a wildland park, provincial recreation areas and public land use zones — have become a flashpoint in Alberta politics.

At the centre of the debate is the question of what it means to responsibly enjoy the outdoors — and can the landscape sustain ever more motorized recreation, hunting, fishing and random camping in an increasingly popular backcountry… especially one that’s dotted with industrial development?

A frozen Abraham Lake at Hoodoo bay sports its signature winter bubbles. In the distance Elliot Peak is visible on the left with Mount Stelfox fanning out to the right. Photo: Darwin Wiggett

Stelfox was one of 37 retired fish and wildlife officers, technicians and biologists who signed an open letter to Alberta premier Rachel Notley earlier this month.

It started with an e-mail list-serve that’s been connecting retired fish and wildlife workers — “us old timers,” Stelfox calls it — for more than 15 years. Don Meredith, the founder of the listserve, told The Narwhal that this is the first time the group has been moved to make any sort of public statement about any issue.

“We like to hunt and fish in the area,” Meredith said. “And we know that the area has been neglected for quite a long time.”

In writing an open letter to the premier, they hoped Albertans would take note of the ecological pressures facing Bighorn Country.

“It can’t be a free-for-all anymore,” they wrote in their letter. “We have tested the limits and many indicators, especially fish and wildlife populations, have signalled to us we’ve exceeded ecological thresholds.”

The authors point to increased habitat fragmentation and over-use in the eastern section of Bighorn Country.

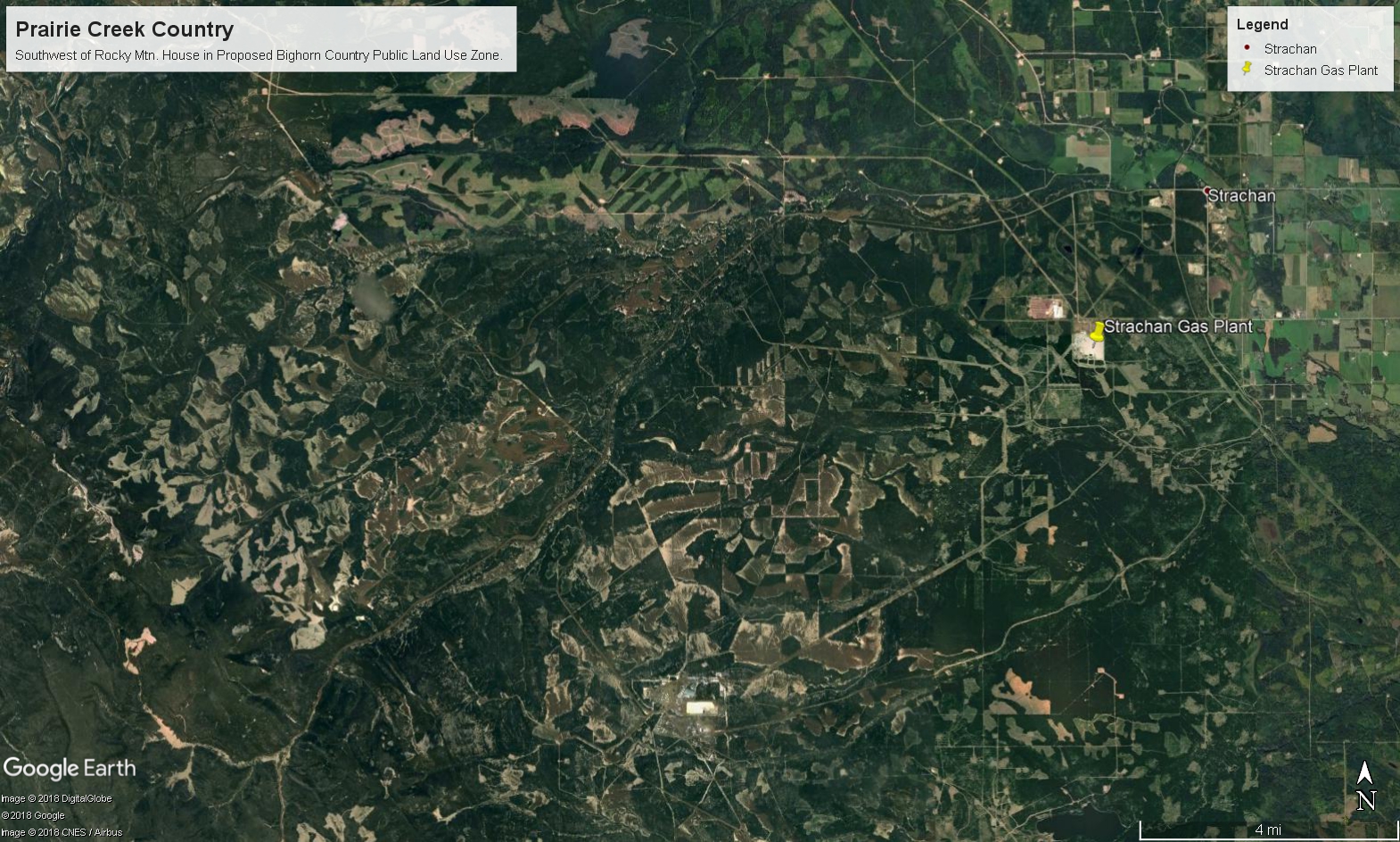

“If you took a [virtual] google [satellite] trip, you’d see massive logging footprint, you’d see a spider web of roads and trails, you’d see oil and gas facilities, and you’d see seismic lines,” Lorne Fitch said, a retired fisheries biologist who signed the open letter.

Part of the landbase covered by the Bighorn proposal is “the industrial landscape,” according to Jamie Bruha, director of land and environmental planning with the Government of Alberta. Much of the area is dotted with clearings from forestry, old seismic lines and roads or other oil and gas activity — what advocates call “a spider web” of development. Image: Screenshot / Google Satellite

According to the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, the Foothills region of the province “experienced the greatest expansion of human footprint,” of all regions across Alberta between 1999 and 2015. The size of the area’s human footprint increased by 11.4 per cent — most of which was attributed to an expansion of forestry activity.

“We need to get a better grip on that industrial land base,” Stelfox said. “We’ve got too many activities all piled on top of each other.”

“It’s gotten so busy,” he added. “And we’ve got so many more motorized recreationists coming in.”

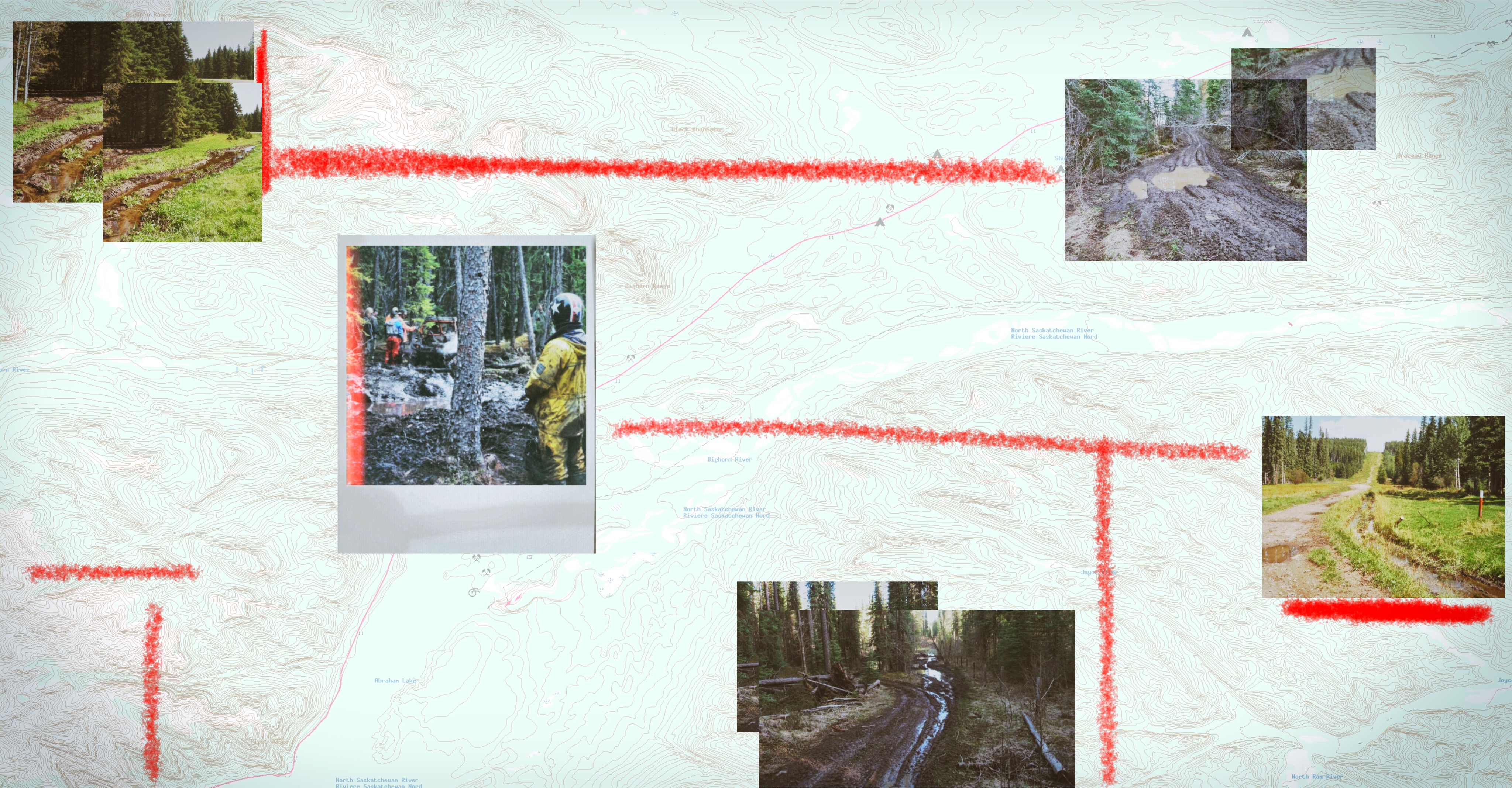

Among the most popular activities in the backcountry of the Bighorn — alongside camping and hiking — is offroading with off-highway vehicles, like quads or dirt bikes.

The 2017 Alberta Recreation Survey found that 13 per cent of people had used off-highway vehicles in the past year — and off-highway vehicle registrations in Alberta increased by 85 per cent from 2004 to 2016.

In 2012, the Alberta Wilderness Association published a study that found off-highway vehicle “use in the Bighorn is increasing every year.”

“The pristine wilderness found within the Bighorn Backcountry area has been… negatively impacted by unmanaged recreational activities,” the study concluded.

Subsequent updates have found trail closures are “being increasingly disregarded across the trail system.”

Off-road vehicles have surged in popularity in Alberta. While there are designated trails for off-road vehicle use in Bighorn Country, some protected areas are still being impacted by their use. Photos courtesy Harry Stelfox. Illustration: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The Alberta Off Highway Vehicle Association did not reply to requests for comment, but Dan Merkowsky, executive vice president of the Recreation Vehicle Dealers Association, told The Narwhal he’s in favour of the proposal.

Eighteen per cent of people in Alberta own RVs, he said, and “a lot of them own toy haulers and haul off-road vehicles with them.”

According to Merkowsky, “there’s always one bad apple in the group that goes into the backcountry and leaves garbage and chops down trees and wrecks things.” The proposal, he said, will allow for better management of recreation in the Bighorn, so everyone can access it and enjoy it.

Advocates for off-highway vehicle use say that most users are responsible, but others who frequent the Bighorn area say not everyone is following the rules — and that’s leading to significant degradation.

Numerous studies have documented the negative ecological impacts of off-highway vehicle use. A 2007 literature review prepared by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management summarized the effects of off-highway vehicles on the land.

Those studies found issues with erosion, soil compaction, introduction of non-native plant species, sedimentation in water sources, dust and wildlife habitat fragmentation — all linked to off-highway vehicle use.

The Alberta government’s environmental monitoring and science division reached similar conclusions when they examined the province’s Castle region last year. “[Off-highway vehicle] use across all seasons causes a disproportionate level of impact and damage,” the report stated.

According to the report, even when off-highway vehicle use is limited, “impacts are often irreversible… and any natural recovery is either slow or nonexistent.”

“People think that it’s their right to use [off-highway vehicles] anywhere on public land,” Fitch said, the retired fisheries biologist. “It’s not a right, it’s a privilege.”

As the divide deepens between proponents and critics of the government’s proposal, much heated rhetoric has been circulated about what the plan would mean for the area.

According to Katie Morrison, conservation director of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), there’s a lot of misinformation floating around about what the proposal will mean for Alberta.

She outlined the myths when she spoke to The Narwhal. “The entire area is not becoming a park,” she said. And, she added, “it’s not closing the area down.”

But critics of the plan say the Bighorn area will be shut down entirely.

United Conservative Party MLA Ron Orr wrote a column in a local paper last year suggesting that “CPAWS and Y2Y are lobbying the government for more restrictions… If they succeed, all the local user groups may well find themselves shut out of camping, hiking, fishing, hunting, cycling, horse riding, Off-Highway Vehicles (OHV) and snowmobile use.” (Orr did not respond to a request for an interview by press time.)

The Bighorn Country proposal, however, says that motorized vehicle use will continue on existing designated trails. “No rollback in designated OHV trails is planned,” according to the plan.

But that reassurance didn’t stop critics like Orr from stoking fears the area will be sealed off for for lovers of the backcountry. “You may never again have the freedoms you are about to lose,” he wrote last fall.

“Your children will be curtailed to paved parking lots and government run campgrounds.”

That’s not how CPAWS sees it. “Obviously we want [Bighorn] available for people to go out and recreate — as all protected areas in Alberta are,” Morrison said. “But we need to make sure we’re doing it in a responsible way.”

The Bighorn Country proposal covers an area of 1.8 million hectares — just under 3 per cent of Alberta’s land base. Part of the area is largely regarded as backcountry, while the eastern section is much more industrial.

The proposal has been in the works since at least 2010 under the North Saskatchewan Regional Plan — before the NDP came into power in Alberta.

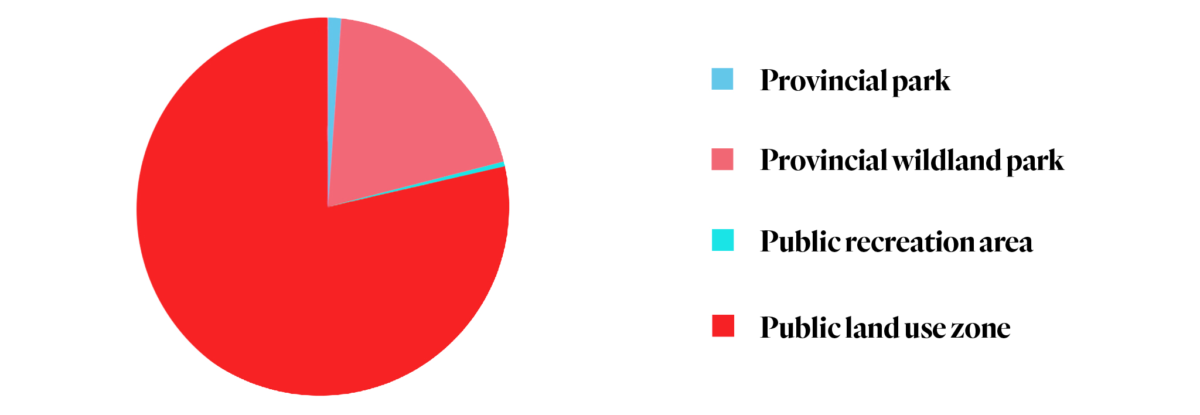

Under the proposal, roughly 78 per cent of the area will be categorized as a public land use zone. Less than one per cent will be designated in provincial parks, and 20 per cent will be classified as a wildland provincial park.

Bighorn land use plan breakdown. The vast majority of the land included in the Bighorn Country proposal would be classified in public land use zones — where all new industrial activity would continue to be permitted, and off-road vehicle use would be allowed on designated trails. Graphic: Sharon J. Riley, Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The different uses allowed in the various types of areas are laid out point by point on the government’s website.

“There is a park area and a public land use zone area,” Dana Mackie, assistant deputy minister of Alberta Environment and Parks, said in an interview. “The two are very distinct and very different… The public land use zone area is not an area for conservation or protection…. It’s managed for many values including commercial, industrial, agricultural, forestry, tourism, recreation and environment.”

The proposal includes two public land use zones. One is already in existence, and would have “slightly amended boundaries,” according to Mackie.

The other would be brand new — the West Country public land use zone.

“This is very much the working landscape,” Jamie Bruha, director of land and environmental planning with the Government of Alberta, told The Narwhal in a phone interview. “It’s the industrial landscape.”

The area is currently undesignated public land, meaning there are few restrictions on recreational use — other than general laws about littering and crossing streams. Bruha told The Narwhal that government data shows 10,000 off-highway vehicles use the area on any given long weekend in the summer.

“We have noticed a drastic increase in the recreational pressures on these landscapes,” Bruha said, noting that off-highway vehicle users have long used oil and gas roads and seismic lines to recreate in the area.

This has led to environmental degradation. In one area, Rocky Creek, he said “fish were becoming trapped in ruts created by [off-highway vehicles].”

The creation of a public land use zone, he hopes, will mean recreation can be better managed — and, he pointed out, a stakeholder group will decide what areas will be designated for off-highway vehicle use, should the proposal move forward.

The goal, he said, is to “improve the recreation experience [and] minimize some of the industrial conflicts we’re seeing.”

Of the 1.8 million hectares covered by the proposal, 14,931 hectares will be protected in the three new or expanded provincial parks and 369,395 hectares will be part of the new wildland provincial park.

The priority with the creation of new provincial parks, according to Philipp Hofer, regional director for the central region of Alberta Parks, is “making sure recreation is happening in the right places,” and minimizing conflicts.

Photographers at Windy Point on Abraham Lake, Kootenay Plains in Bighorn Country. Photo: Darwin Wiggett

As the popularity of the backcountry increases, he worries about safety hazards. For example, in some areas, he said, dozens of vehicles are parked along the highway on some weekends, while drivers hike local trails. This proposal will allow the government to create new parking lots.

But the idea that parks will turn the backcountry into a sort of Disneyland is a misnomer, Hofer said. The capital budget for the next five years is $25 million.

“That is certainly not the kind of budget we’d use to pave paradise.”

Under the proposal, existing oil and gas activity, along with sand and gravel extraction, will be permitted to continue in all areas, though new surface access will be limited to the public land use zones. (Subsurface oil and gas development will still be allowed in parks and recreation areas, through directional drilling.)

Commercial forestry would also be allowed in public land use zones, and existing grazing would continue, though permits would need to be issued in some cases.

And while many industrial activities would be able to continue under the proposal, there is another reason the Alberta government is pushing to increase the protected areas within the province. Under Aichi Target 11, an international commitment, the province needs to protect 17 per cent of Alberta’s wilderness by 2020.

Only 1.4 per cent of the foothills region of Alberta is currently part of a park or protected area, while 14.6 per cent of the province as a whole is protected. The protected areas created under the Bighorn proposal would increase that provincial number to 15.2 per cent.

The scenic Highway 11 at Windy Point in the Kootenay Plains region of Bighorn. Photo: Darwin Wiggett

Morrison said another myth floating around, “is that the area is already protected by current policy.” Since the 1970s, management of the area has occurred under the a document titled “A Policy for Resource Management of the Eastern Slopes,” — a document last updated in 1984. And Morrison is quick to point out that policy is different from legislation.

“Success of the policy has… been dependent on the private sector, the public and the Alberta government voluntarily following the guidelines,” she said. “Legislated protection… ensure[s] the important values of the Bighorn are protected in perpetuity.”

According to Morrison, Bighorn Country is a “priority place for protection.”

“The Bighorn is the source water for Edmonton,” she said, adding that 88 per cent of water — that people drink, bathe in, water their gardens with, use for industry — comes from the Bighorn.

The area is also an important habitat link for grizzly bears, wolverines, bighorn sheep, elk and other wildlife.

“There is a missing piece there that is currently not secured or protected,” Morrison said of the corridor that allows wide-ranging species to move from north to south.

Bighorn country, she said, is “home to some of our most charismatic wildlife species.”

“It’s one of those places where you really feel connected to Alberta’s wilderness.”

Right now, according to Morrison, the conversation is dominated by a “very loud minority.” A poll commissioned by CPAWS in December found that nearly 75 per cent of Albertans support the proposal.

Only nine per cent of respondents indicated that their own recreational activities were a higher priority than preserving the environment.

But, it seems, the conservation plan has — at least in part — become a debate over what some perceive as Alberta values: freedom to explore the province’s backcountry, unfettered by government intervention.

In recent weeks, the debate over public lands has been marred in controversy, as public information sessions were postponed over what the government called “reports of harassment, bullying and intimidation experienced by session participants.”

“This is a tempest in a teapot,” Meredith said, who believes misinformation has led to an overblown argument.

In the meantime, the consultation period has been extended, and Albertans can provide their own feedback directly to the government until February 15.

In their open letter to the premier, Meredith and his colleagues acknowledge that the plan still requires work. “The plan is not perfect,” they wrote.

“But it is the best chance we have to conserve an important component of our Alberta wild heritage for future generations.”

For them, it’s not about politics.

“I think conservation of our natural resources shouldn’t be a partisan issue — or shouldn’t have been made a partisan issue,” Fitch said, the fisheries biologist.

Stelfox agrees: “As our population grows — as our ability to get out on to the land grows, as tourism visitation grows — we’ve got to get it right.”

Albertans can provide feedback on the Alberta government’s Bighorn Country proposal until February 15, 2019.

* This story has been updated to reflect that the capital budget of $25 million is for over five years, not 25 as originally reported.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...