‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

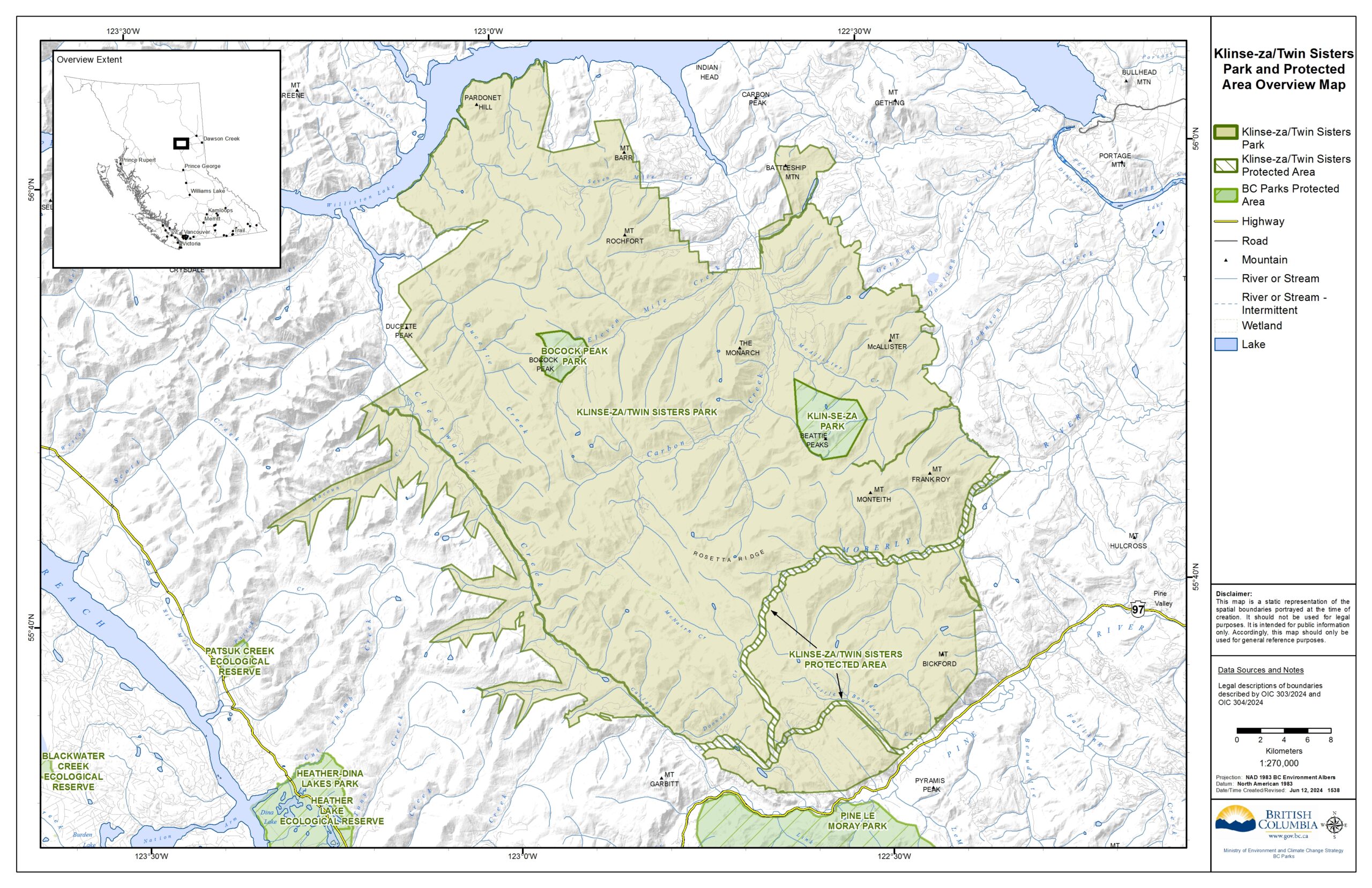

A significant stretch of endangered caribou habitat in northeast B.C. has been permanently protected in the newly expanded Klinse-Za / Twin Sisters Park, First Nations and the B.C. and federal governments announced today.

The announcement comes more than four years after West Moberly First Nations, Saulteau First Nations and the provincial and federal governments agreed to work together to recover caribou herds teetering on the brink of extinction. The deal included a commitment to create a park to protect crucial caribou habitat in the mountainous area northeast of Mackenzie and west of Hudson’s Hope and Chetwynd, in the heavily industrialized Peace region.

“We’re showing that when we work together collaboratively — not just say we’re going to work together, but we actually sit down and start applying the principles of working together — we can do some amazing things,” Chief Roland Willson of West Moberly First Nations told The Narwhal.

Klinse-Za Park (pronounced Klin-see’-za) was just 2,700 hectares — about seven times the size of Vancouver’s Stanley Park — in 2020 when the deal was forged. Over the next two years, the park was expanded to 30,000 hectares. Today’s announcement extends the park to nearly 200,000 hectares, making it almost two-and-a-half times the size of E.C. Manning Provincial Park in the Cascade Mountains in the province’s southwest.

Alongside vital caribou habitat, the park also protects the Twin Sisters, two mountains of cultural importance to Treaty 8 First Nations.

In contrast to other recent conservation announcements — including the $1 billion nature agreement announced late last year — the B.C. government shared news of the Klinse-Za / Twin Sisters park quietly in a press release Friday morning with comparatively little fanfare, even though the provincial park is the largest established in B.C. in a decade.

The greatly expanded B.C. park makes a noteworthy contribution to the provincial government’s pledge to protect 30 per cent of provincial land by 2030, in keeping with global commitments to protect nature at a time when close to one million species are at risk of extinction, many within decades.

“This announcement is a good thing for everybody,” Willson said. “We’re trying to bring balance back. Maybe it’s not just all take. We gotta give some back, or we’re going to wind up in this situation where we have nothing left — truly nothing.”

In a press release, B.C. Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy George Heyman said, “The decline of caribou is a complex problem, and we continue our work to stabilize populations. Providing a large area that protects caribou and their habitat from development is a critically important step forward that is consistent with the agreements we first announced in 2020.”

Tim Burkhart, director of landscape protection at the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, called the announcement a “really important milestone” for Indigenous-led caribou recovery.

Caribou populations in the Peace region have suffered dramatic declines due to the combined pressures of hydro dam development, oil and gas production and extensive logging and road-building. In the last century, caribou have declined by 55 per cent in B.C., according to the B.C. government news release.

The Klinse-Za herd declined from about 250 caribou in the 1990s to just 38 in 2013, according to a 2022 study in the journal Ecological Applications.

Since 2014, West Moberly First Nations and Saulteau First Nations have led a successful, though costly, maternity pen project.

Each year pregnant caribou and, later, their calves are kept in maternity pens, safe from natural predators such as wolves and under the watchful eye of Indigenous Guardians until the calves are strong enough to have a better chance of surviving outside the pen.

A herd “within months of being extirpated” has tripled in size, Willson pointed out. Though the Klinse-Za herd remains at risk of extinction, the population had recovered to 138 caribou by 2023, aided by the maternity pen and wolf culls.

Two existing maternity pens will now fall within the boundary of the expanded park, according to the B.C. government.

“Our sacred Klinse-za / Twin Sisters area will now be protected for our people forever,” Chief Rudy Paquette of Saulteau First Nations said in the press release. “This is another step in the process by which we are proving that we can recover endangered species and protect the sacred lands of First Nations people, while also providing for healthy ecosystems and diverse economies.”

Burkhart lauded the success of the maternity pen program. “Folks working on orca, salmon and other species across the world should really look to the leadership of West Moberly and Saulteau and how they brought a local herd back from the brink,” he said.

The expanded protected area was “designed specifically to create habitat that is abundant enough to bring the herd to a self-sustaining level,” Burkhart said. “So we know now that when the baby caribou are released from that maternal pen, they have a place to stand and a landscape that will support them going forward.”

The two First Nations, B.C. government and other partners will work together to develop a management plan for the park to protect Treaty Rights and Indigenous cultural values, restore forestry roads and logged areas to natural habitat and manage recreation sustainably, the release said, noting snowmobiling has been restricted in most areas of the park since 2021 to protect caribou.

Industrial activity has also been restricted in the park for several years. The federal government has provided $46 million to compensate industry and tenure holders affected by the implementation of the 2020 partnership agreement, as well as $10 million to support a regional economic diversification trust for the region, according to the news release.

Habitat protection is crucial to the long-term survival of at-risk caribou herds. Although forestry and other resource activities may be allowed in areas adjacent to the B.C. park, Burkhart noted the 2020 agreement prioritizes caribou recovery when such activities are planned.

While the Klinse-Za herd has seen remarkable growth, the population is a long way from being large enough to allow West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations to once again harvest caribou for food. In a 2023 study, the nations worked with scientists to estimate “meaningful abundance”: how plentiful the Klinse-Za herd would have to be to harvest enough caribou for 15 meals for every family in their nations over one winter, without harming the herd’s stability. They found the herd would need 3,000 animals — meaning it would need to increase by at least 20 times.

The Klinse-Za / Twin Sisters Park also offers habitat for three dozen other at-risk species, including grizzly bear, wolverine, fisher and numerous plant and insect species.

Willson said the Klinse-Za mountains are sacred to the Dena-za people and were once a place of refuge.

“In times of need, we would go to the mountains, and they would take care of us,” he said. “There were lots of caribou, lots of sheep, lots of goats, lots of moose. The waters were clean. The fish were good to eat. There was an abundance in the mountains.”

Today, Willson said, there are hardly any caribou or mountain goats left and the fish and waters are contaminated. But the nations are working to restore habitat where they can.

Willson said it took more than 20 years to bring the Klinse-Za park to fruition. The process, which began under the BC NDP government in the 1990s, was halted when the BC Liberals (now called BC United) came to power in 2001 and only resumed after the BC NDP returned to power 16 years later.

Countries around the world, including Canada, have agreed to protect 30 per cent of their land and waters by 2030 as part of a global effort to address the growing biodiversity crisis. According to the World Economic Forum, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse represent one of the largest risks the world faces over the next decade, with dire consequences for the environment, humankind and economic activity if not addressed.

But scientists warn nature may require far more protections. Up to 50 per cent of lands and waters globally may need to be conserved to maintain biodiversity, according to a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

According to the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database, B.C. is leading the provinces in meeting targets. As of December 2023, B.C. had conserved 19.7 per cent of its land. The expanded 2,000-square-kilometre Klinse-Za park covers approximately 0.2 per cent of the province.

But some groups question the B.C. government’s accounting.

Earlier this year, the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society published a report that raised concerns B.C. inflated its progress by counting fragmented stretches of forest that may not have permanent protection toward its conservation targets.

At the time, the B.C. government said it was working on a new approach to assessing conserved areas.

“It is a bold vision, but there is a path to meeting 30-by-30 through Indigenous-led conservation,” Burkhart said.

“This is the scale of new protected areas that we want to see,” he said of the newly expanded park. “We need a lot of pieces like that to make it work.”

Willson pointed out caribou need vast swaths of land and it’s still uncertain if the expanded park will be enough. He said the nations will have to monitor the impacts and continue to restore habitat. “We’ve got to do what we can, where we can,” he said.

“Our future generations are going to know that the caribou are still here because of the work that we’ve done today.”

Corrected on June 14, 2024, at 11:27 a.m. PT: This story has been updated to note B.C. is leading the provinces in meeting conserved area targets, not, as previously stated, the provinces and territories. The Yukon has protected 21.1 per cent of land in the territory as of December 2023, B.C. has protected 19.7 per cent.

Corrected on June 15, 2024, at 1:29 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to remove a passage that incorrectly stated the expanded park also protects habitat for the Quintette and Narraway herds. While habitat used by these herds is covered by 2020 partnership agreement, it is not protected by the expanded Klinse-za / Twin Sisters Park.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...