Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

When Barry Timpany looks out his window, he can see clear across the Creston Valley: the mountains lined with trees and the valley bottom dotted with farms. He lives in Wynndel, B.C., a community of about 650 people. One day last November, he opened the local paper and saw a notice that a private logging company was applying to use forest service roads to access the Duck Creek watershed, up the hill right beside Wynndel, which supplies water to people’s homes, farms and a sawmill.

Timpany was instantly concerned. Prior logging on private land had already left a large clearcut looming over Wynndel. He worried how logging would impact their water supply, especially because private lands are subject to less regulation than logging on Crown land. Other community members were concerned as well. But they learned there was little to be done — since it’s privately owned, members of the public have no say on how or whether it proceeds.

Wynndel is about halfway between Nelson and Cranbrook in the Kootenays in southeast British Columbia. Private logging is widespread in the region. Some communities have tried pushing back, but their efforts have run up against private ownership and lax regulations. After residents of Glade, a nearby community, mounted a legal challenge to private logging near their community water supply, a B.C. Supreme Court judge concluded British Columbians do not have any inherent right to clean drinking water.

Timpany says forestry has gotten out of hand, and the lack of management has led to forestry becoming a “corporate slaughter.”

Timpany worries the impact on the watershed could be “devastating” to local homes and businesses. His farm has never had an issue with water, but he worries reducing trees in the watershed will reduce how much water it can hold and cause it to dry up.

And the operation is just one more example in the long line of frustrations he has with how forests are being managed in the province. Forestry companies and the government will “scream it’s about jobs,” Timpany says, but he’s not convinced. He points out many raw logs are exported rather than being processed in the province by Canadian workers. A study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives estimated that over 3,600 jobs could be created in B.C. if exported raw logs were processed here instead.

“They don’t give a flying farmer about jobs,” Timpany says. “They’ll shut down mills to mothballs, as quick as they can.”

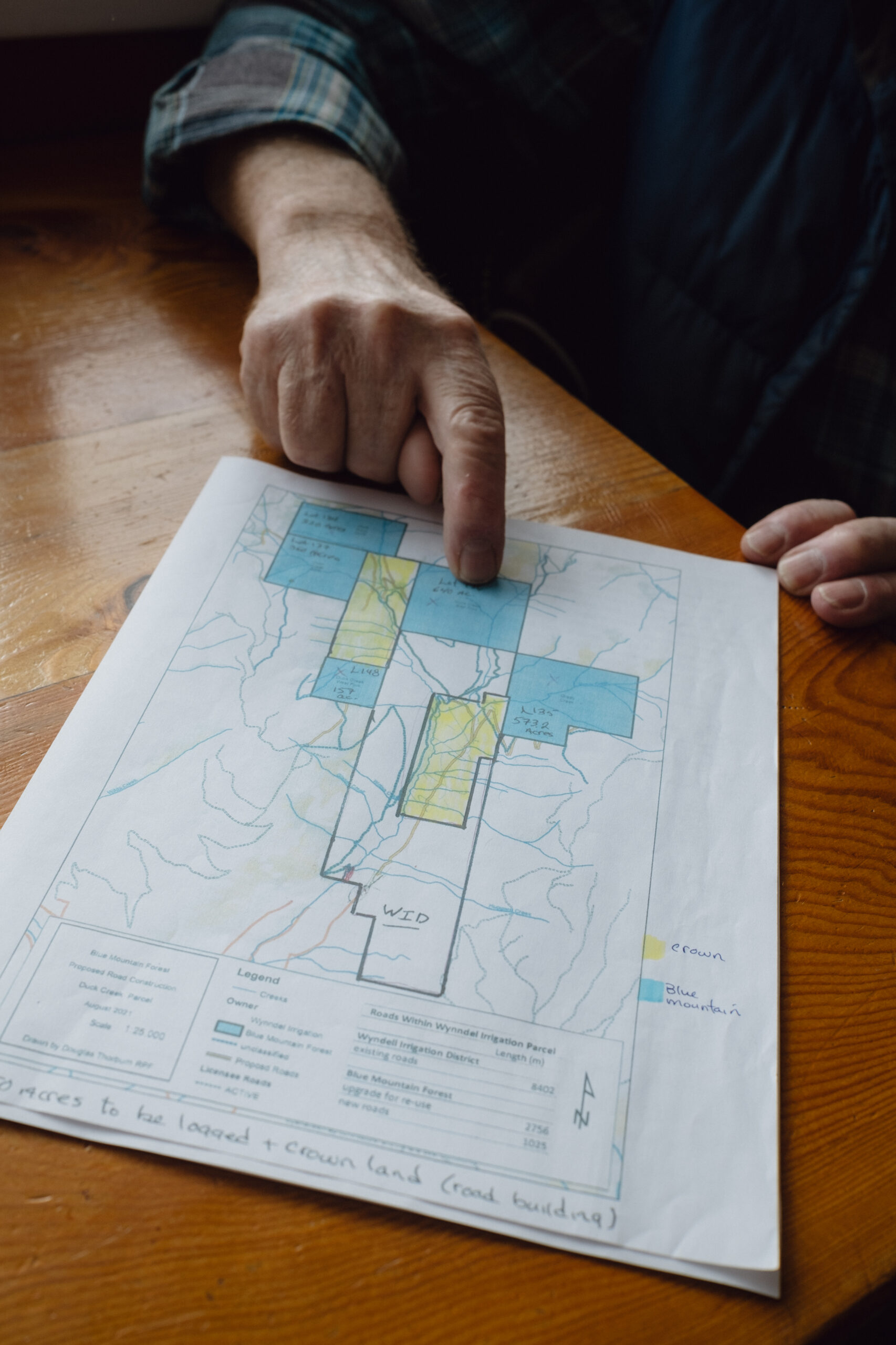

The Duck Creek watershed is 5,221 hectares, 854 hectares of which is owned by Blue Mountain Forest Land Ltd. and operated by forest management company Monticola Forest Ltd. Another 505 hectares are controlled by the Wynndel Irrigation District for the community. The rest — 3,827 hectares — is Crown land, licensed to Canfor, one of the biggest forestry companies in the province. Both Canfor and Blue Mountain are moving towards logging in the watershed.

There’s nothing community members can do to stop the logging in Duck Creek — but Blue Mountain was required to consult the public as part of its application to use forest service roads to access its land. Blue Mountain also plans to apply to build roads that would need to cross private property.

The Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship told The Narwhal a decision on Blue Mountain’s application is not imminent, and a decision may take one to two years.

Eddie Petryshen is a conservation specialist with Wildsight, a Kootenay-based nonprofit focused on protecting biodiversity and sustainability. He says the majority of private logging in the province occurs on the Sunshine Coast and Vancouver Island and in the Kootenays, due to land being given to settlers as payment for rail construction. The land was sold despite the fact that First Nations had never ceded it to the Crown, a legacy that continues to impact Indigenous Rights today.

According to the province, five per cent of land in B.C. is private land, which amounts to 4.5 million hectares. Of that, it says just over one million hectares (or around one per cent of the province) is privately managed forest land.

Brian Churchill, branch board president of Wildsight’s Creston chapter, is also a retired wildlife biologist. He says private logging is highly visible in the Kootenays. He saw a piece of private land between Creston and Wynndel was clearcut this winter.

“Nobody knows who did it, nobody knows who owns it, nobody knows where the wood went to, nobody knows what the long-term plans are.”

Even without delving into the thorny issue of giving away Indigenous Peoples’ territory, private logging brings challenges to communities today, Petryshen says. Private logging is not subject to annual allowable cut, stumpage fees or restoration measures that logging on Crown land is. The Private Managed Forest Land Act regulates private logging, and critics like Petryshen say it lacks environmental protections.

“There’s no requirement for a sustainable harvest,” Petryshen says. “They can harvest as much as they want.” He says it’s easy to switch the land designation when they want to sell it — meaning that for a fee, the land previously meant to be kept as forest can easily be switched to land to be sold for other purposes like real estate.

“It’s a strip and flip mentality.”

This is Petryshen’s biggest concern. Forests can regenerate, even if restoration isn’t the best — but when the land is converted for other uses, the forest is gone forever.

“There’s just a lack of regulation and a lack of protection for downstream communities,” Petryshen says. “It makes Crown land logging look very good, and that is something that scares me.”

The big clearcut that looms over Wynndel was logged years ago by Mike Jenks, who has earned a notorious reputation among some B.C. communities for clearing forests on private land.

“You can see it from all over the valley, this bald-ass mountain,” Timpany says.

Timpany emphasizes he is not against logging. “I come from a logging family … But the way we log now is just deforestation.”

Stephen Aryan, a mechanical engineer who grew up in Creston, bought the land that had become “a highly visible scar on the landscape.” He’s been experimenting with an autonomous agricultural robot arm and practices to reduce waste and use less fertilizer and water. His sister runs a farm-to-table restaurant; together, the siblings create juices, wines and ciders for their business, Pippin Point. Aryan’s dream is to scale up their operation into a system they can share with others to make farming more economically feasible and less labour intensive.

His other dream is to eventually bring back forest to the hillside and stabilize the landslides and water fluctuations caused by the clearcut.

The Blue Mountain and Canfor operations mean that trucks will be driving through a forest service road that already cuts through Aryan’s property. The dust they’ll kick up near the restaurant is not ideal, but is manageable, he says. He’s more concerned that the narrow, steep road won’t be safe for logging trucks.

“[The road] is serving residents. There are kids around. It’s not a road set up for adequately handling semi traffic, especially with blind corners,” he says. “In my mind, it’s inevitable an accident will happen.”

Aryan says he wants to support local loggers. He knows businesses are struggling to access quality trees — a challenge created by historic logging practices, which cleared out ecosystems and neglected to replant robust forests. “These companies are trying to make a living,” he says. “There’s an economic benefit to the area and all that. I don’t want to block people from having jobs. But it would be nice if it was done in a manner that still enables a forestry industry for generations to come.”

He also acknowledged that the state of the land he’s trying to revitalize, logged by Jenks, has put Blue Mountain in a tough position. “The very first major private logging [in Wynndel] … is very visible, it is very ugly, and it came with quite a few problems.”

Rainer Muenter, owner of Monticola, says he sees how the previous clearcut instilled distrust in the community.

“It is common that some logging contractors buy larger pieces of private land and then slick it, and that has happened to Wynndel,” he says. “But it’s not what we are doing.”

Muenter says two-thirds of Monticola’s operations is selective logging, and the company plans to remove 30 to 40 per cent of the trees in Duck Creek. “There will be changes, but they will be relatively minor,” he says, adding that they haven’t gotten that far yet.

“We only have applied for road access,” he said, without providing a timeline for when logging was likely to begin. The long-term goal, Muenter says, is to manage the forest for generations. Because of forest fires in the first half of the 20th century, the majority of trees are relatively young.

Muenter says he has not heard complaints about the roads application, which he attributes to the fact most jobs in the area come from the Canfor mill, logging and farming. “That’s how everybody makes a living around here,” he says.

In response to residents’ concerns about water, Muenter pointed to the 2020 hydrology report by APEX Geoscience Consultants Ltd., commissioned by Blue Mountain, which concluded the company’s plans to selectively log the watershed have “low risk” of impacting peak flows. It found moderate to high risk of impacts to water quality due to turbidity associated with landslides. The report concluded the company must also do an assessment of terrain stability or landslide risk.

Muenter says Blue Mountain is part of the private managed forest land program, established under the Private Managed Forest Land Act. The program, which is voluntary, includes regulations on water like stream buffers — though critics say the environmental protections don’t go far enough. “We have chosen to become a managed forest,” he says. “The Ministry of Forests oversees us and comes for audits and inspections,” he adds, explaining that each managed forest is audited every five years.

Muenter said he hears some support selective practices, but he’s also heard opposition from others, who say to get logs out faster and not leave so many trees behind. “There’s a big crunch for trees,” he says.

In 2019, the province announced a review of the Private Managed Forest Lands Act, but no amendments to the act have been made. The ministry said it is still working with the Private Forest Landowners Association and Managed Forest Council “to modernize the Private Managed Forest Land Program.”

“Many of the issues raised during the review are being addressed through government’s work to make sure forestry supports ecosystem values – including through the $1-billion Nature Agreement – as well as reconciliation, wildfire prevention, local community benefits, and made-in-B.C. wood manufacturing and innovation,” the Ministry of Forests told The Narwhal in a statement.

It said private landowners are subject to inspections and legislation like the water sustainability act.

“B.C. is making watershed security a priority. The Watershed Security Strategy being developed by B.C. and partner First Nations will ensure that the province’s watersheds are well managed and resilient in the face of climate emergencies, drought and competing needs for water,” it said.

According to a Government of B.C. website, public engagement on the watershed strategy began in 2021. The strategy was scheduled to launch in the winter of 2023-2024 and begin implementation in the winter of 2024, but no updates have been shared since the public feedback period concluded.

The private logging in Wynndel also raises questions around British Columbians’ right to clean drinking water, as potential water scarcity in the future looms.

“There just is nowhere in the law where you can look and say, ‘There it is — there’s my right, I have a right to clean water,” Justice Mark McEwan said in 2019, ruling against the community of Glade in a dispute with timber companies.

Herb Hammond, an ecologist and retired forester who lives in the Slocan Valley, assisted residents of Glade in their fight.

When he thinks about the decision, he says, “I’m as disgusted today as I was then.”

In 2023, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act was amended to recognize every individual in Canada has a right to a healthy environment.

The Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship and Ministry of Health did not answer The Narwhal’s question if British Columbians have a right to clean drinking water.

In a joint statement, the ministries said clean drinking water is “critical” and that there are regulations around treating water.

“If a person considers that there is a threat to their drinking water, the person may request the drinking water officer to investigate the matter,” the statement read.

The provincial government has warned that worsening drought across B.C. can impact households and businesses. In 2024, the province recorded the lowest April snowpack level since 1970, following “persistent, severe” drought conditions that had gripped the province since fall 2022.

Beyond bringing water to communities, watersheds are integral to ecosystems. Tree cover in watersheds slows snowmelt so the land isn’t run over by floods and landslides, Hammond explains. Older forests are also more resilient to wildfires. They also provide habitat for wildlife like caribou. The Purcells-South herd of southern mountain caribou was once in the region but are now locally extirpated.

Muenter says some management in the Duck Creek watershed is needed because “the fuel loads and the fire risk are high.” As well, the proposed roads could be used to get to the source of the fire and “protect the watershed from larger-scale wildfire, because we will be able to keep the fire small,” he says.

Speaking generally, Hammond agrees that selecting areas at high risk of wildfire and thinning between the trees can help — which means removing “fire ladders,” shorter trees that fire travels up to reach the crowns of big trees.

But wildfire prevention is “not taking the best trees,” he emphasizes.

“Wildfire risk has been adopted by some people as an excuse to log,” Hammond says, but there’s no evidence that it’s an effective strategy. “There’s no such thing as fireproofing… You get the right conditions, and any forest will burn.”

Blue Mountain is “a pretty good operator,” Churchill says. To him, the bigger question is whether logging in community watersheds should be happening at all.

He wants to see B.C. come up with a water sustainability plan to manage logging in watersheds. He also emphasized he is not anti-logging, the communities aren’t anti-logging — but he wants to see more public accountability and planning to address uncertainty around water supply.

Churchill and Petryshen also want to see an updated, more stringent Private Managed Forest Land Act.

For small scale landowners, maybe the existing regulations are relevant, Petryshen says. But “If large landowners are operating industrially and at that scale, they should be subject to the same regulations Crown operators are.”

Timpany says “if we want to fight climate change, we need to leave forests to do the work they’re meant to do,” still managing them to mitigate fires and doing some logging, but avoiding clearcuts in key watersheds and increasing oversight of forestry operations.

The trees are here “for all of us,” Timpany says. To clean the air and provide habitat — not make a select handful rich, he argues.

“There’s just too much greed.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...