The federal government ‘sees a long-term future for the oilsands.’ Here’s what you need to know

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

This story was first published on Great Lakes Now, a monthly show and daily news site that offers in-depth coverage of news, issues, events and developments affecting the Great Lakes and the communities that depend on them.

One of the last known (and most famous) blue pike was landed by hook and line in 1962. In 1983, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared the blue pike extinct. Yet, nearly 40 years later, the population remains robust and healthy — in the hearts and minds of countless anglers.

Part of that is due to a feature story written about the bygone fish.

“I knew when I wrote the story it would capture peoples’ imagination for a long time and I get people that still reach out to me,” said Chris Niskanen, a former St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter and former Minnesota Department of Natural Resources media relations representative. “I see it all over the internet and you can see where it’s been reposted, cut and pasted and clips of it showing up in fishing forums.”

In 2008, the article “In Search of Blue Pike” appeared in Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, a Minnesota Department of Natural Resources publication. It came into existence when Niskanen got word that a tiny, remnant population might still exist in a remote northern Minnesota lake more than 800 miles from Lake Erie, the blue pike’s native home, though that didn’t turn out to be the case.

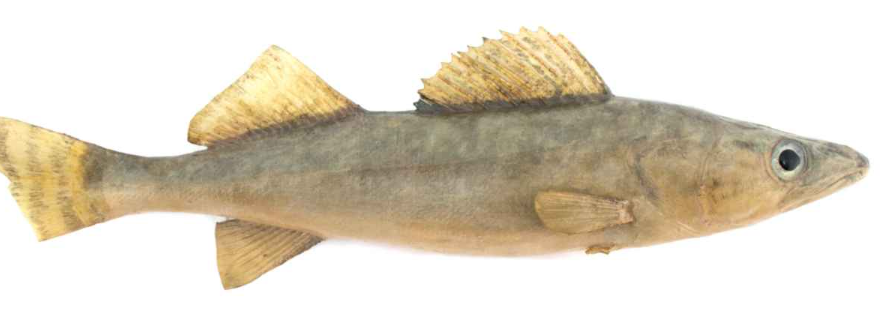

Sander vitreus glaucum looked strikingly similar to walleye, though it grew to just about three pounds, had a noticeably blue-gray hue and distinctively larger eyes than a walleye. To say they were plentiful would be an understatement. Commercial fishing records show more than 3.1 million pounds were netted in 1885. Between 1950 and 1957 records show that up to 26 million pounds were taken in a single year. Blue pike lunches and dinners at taverns and restaurants were as common then as Lake Erie yellow perch meals are now. But by 1959 the catch had plummeted to just 89,000 pounds.

By 1964, fish dealers sold just 200 pounds. The Lake Erie blue pike party was over.

Port Clinton, Ohio, resident Al Wozniak, 90, remembers. He worked as a commercial fisherman more than a half century ago.

“I was young when we fished for them,” he said. “We fished for Independence over there in Sandusky. All their boats were named after fish. There was Blue Pike, Perch, Sauger. There was a lot of blue pike at one time. Then they just disappeared like everything else does.”

Wozniak said blue pike were still being caught there when he left the business.

“It had to be the middle or late ’50s when they started to go, might’ve been the ’60s,” he said. They were deep water fish, and they were pretty good to eat. They got about 12 or 18 inches.”

The window of time for locating anglers who fished for and remember blue pike is quickly narrowing. Niskanen compared it to the memory of Martha, the last passenger pigeon, who died in 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoo.

“There was a point when there was only one person left who remembers seeing the very last passenger pigeon, you know? And when that person’s gone …” he said.

One good example: Jack Tibbels operated Tibbels Marina in Marblehead, Ohio, for decades. In 2014, shortly before he died, the 76-year-old recalled fishing on Lake Erie in the Marblehead area decades earlier.

“Years ago, we would go out in the evenings from about seven until midnight and catch blue pike,” he explained in a previous interview. “We didn’t target them, but we caught a lot because they were available.”

Tibbels said that using lanterns and fishing a bit offshore, they would haul in plenty that ran about 12 to 15 inches, the biggest being about two-and-a-half pounds. They filled tubs with blue pike in a few hours.

“Smaller fish, very good eating,” he said.

“I was talking to a fisheries biologist one day, and he was talking about these files he had in a draw he’d inherited from a predecessor,” Niskanen said. “He was looking at these documents where these blue pike, or alleged blue pike, were brought from South Dakota and stocked in this very small lake in northern Minnesota. The records are incomplete, and if you look at them there are a lot more questions than answers.”

When asked to better describe the lake and its location, Niskanen balked.

“Oh, I would never tell you the name of the lake. I made that deal with the fisheries biologist who agreed to take me there,” he said. “He was reluctant to take me because I was a reporter and my job is to tell people stuff.”

The fisheries biologist was among a handful of people who kept casual tabs on the lake’s special fish — which had been secretly stocked by two biologists in 1969. The 525 fingerlings had been raised at the South Dakota hatchery. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources records showed the effort was intended to possibly rescue Lake Erie’s beloved blue pike from extinction, or at least preserve whatever genetics might remain. After that stocking, biologists made pilgrimages to the lake where they netted or caught blue pike.

But were they just blue walleye?

Frequently mistaken for blue pike, some walleye in northern regions — especially Canada — have been found to sport a turquoise-blue sheen. Researchers have concluded the coloration is caused by sandercyanin protein in the fish’s mucous. Unlike blue pike, the blue sheen on these walleye can be wiped off since it’s completely external.

Either way, Niskanen said, he knew a good story when he saw one. Icing on the cake was when a biologist told him about a 1990s clandestine ice fishing trip where they’d caught a pair of blue-hued blue pike-looking fish on the lake. Now years later, he was on the same lake, canoeing to the same area where the fish had been pulled through the winter ice.

All day long he, a Minnesota Department of Natural Resources biologist, a photographer and another angler paddled about reeling in largemouth bass. Just a single suspect fish was caught that day — a walleye. But it held its own magic.

In his article, Niskanen wrote: “The three-pound walleye looked ordinary except for bluish hues around its mouth and fins. At certain angles in the water, it seemed to glow blue. We slid our canoes together and admired its iridescence. [Minnesota Department of Natural Resources] records show the only walleye-like fish ever stocked in the lake were the purported blue pike fingerlings in 1969. We marveled at the possibility that this fish’s ancestors, now museum specimens, were sold by the boatload around Lake Erie. The walleye would be the only blue-hued fish we caught all day.”

Niskanen’s research, including delving through more than 100 pages of old records, found that what were alleged to be blue pike taken in Pennsylvania’s Lake Erie waters were stripped of milt and eggs at a state hatchery, then either eggs or fry sent to a state fish hatchery in Yankton, South Dakota, and from there to northern Minnesota. They were stocked in the lake on Oct. 30, 1969.

Jim Anthony’s father sold tons of blue pike in markets way back in the day, when they were popular table fare and highly abundant. After school, according to Anthony, he would don fish-cleaning attire, grab a knife, and help his father scale and clean the fresh Lake Erie fish.

Some years later, the Conneaut, Ohio, barber caught one in Lake Erie. That was 1962. He was so surprised, the story goes, he offered it to state wildlife staff, who declined. But Anthony was so enamored with the fish because he hadn’t seen one in such a long time, he wrapped it up and threw it into his freezer at home. Then he did something remarkable: he kept it for 37 years.

In 1999, the never-thawed fish finally left the frozen vegetables section of Anthony’s freezer and made its way to University of Toledo, where Carol Stepien gladly accepted it. The fish geneticist, and then-director of the Lake Erie Center, utilized the fish to further her walleye and blue pike research. In 2014, she and a graduate student published an exhaustive study on the relationship between walleye and blue pike. Their work included examination of hundreds of samples from current and historic walleye and historic blue pike. Anthony’s frozen fish was among those.

While the study provided clear scientific knowledge, it was a real downer for treasured blue pike lore: the fish was not a distinct species. And further, it wasn’t even a sub-species according to Stepien, as some scientists had determined in earlier studies.

“They were never distinct from walleye,” Stepien explained in an interview shortly after the study was published. “We used samples from 711 individuals, using mitochondrial DNA sequences and nuclear DNA microsatellite loci. You cannot tell a blue pike individual reliably by any measure from a walleye.”

Stepien’s study determined the blue pike which were once so plentiful were always walleye, though likely from a different breeding population. Over time, its unique features, including the blue hue, smaller size and larger eyes, were developed among the distinct population of walleye for various reasons.

And the fisheries’ quick, catastrophic decline, scientists agree, was the result of a combination of detrimental factors. Stepien’s study cites massive habitat loss during the 20th century including industrial waste, draining of wetlands, shoreline armouring, channelization of waterways and intense dredging operations around Lake Erie. In addition, the study cites high levels of phosphorous in the 1960s, near the end of the blue pike’s existence in the lake, as causing large algae blooms and oxygen depletion.

Peoples’ appetite for the fish didn’t help either. Commercial harvests continued until the very end, when there were no more blue pike to catch. The overfishing and declining population, according Stepien, likely caused blue pike to begin spawning with walleye.

“Most walleye return to spawning grounds and interbreed with their own group,” she said. “When you overfish, this may break down the reproductive structure and lead to interbreedings.”

In the 1960s, Lake Erie was widely declared “dead” due to its pollution and algae. In fact, Dr. Seuss’ book The Lorax included the lines: “They will walk on their fins and get woefully weary in search of some water that isn’t so smeary. I hear things are just as bad up in Lake Erie.” As the lake improved, future printings omitted the Lake Erie reference.

While more common in northern waters, especially Canada, walleye with blue and gray tints are still caught in the U.S., including in Lake Erie. And when anglers land one, they’re often curious. In the past, people would frequently contact fisheries staff, sometimes showing up with a fish in tow.

“I’d say we don’t have as much of that anymore,” said Travis Hartman, Lake Erie program administrator for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. “It’s more of us seeing a social media post where someone’s posted a photo and asking, ‘This really has a blue tint to it, is it a blue pike?’ ”

If an angler catches a blue walleye, Hartman suggests going the social media route, because the blue pike is most definitely gone.

“We have a huge commercial fishery and a strong angling fishery here, and if there were any number at all we’d see them. The best example is cisco, or lake herring, which used to be abundant in Lake Erie,” Hartman said. “Now they’re functionally nonexistent. We do see one or two of those a year, there are remnant cisco in the lake whether they’re migrating or actually reproducing here. The point is, even the rarest of fish, we’ll see them occasionally and there just aren’t any blue pike.”

Despite the fact the cautionary tale of blue pike appears to be a dead end both scientifically and practically, it still regularly blooms anew in fishing forums and on social media.

“I think the bigger sort of world view here is that people want to believe in their hearts that human beings haven’t destroyed everything, that maybe through some chance there’s still some true blue walleye,” Niskanen said. “And so that makes these kind of stories go on forever, people holding out that some of these creatures still exist.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Notes made by regulator officers during thousands of inspections that were marked in compliance with...

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...