Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

When an oil spill leached into two Toronto creeks last summer, the cleanup didn’t totally go as planned. Despite the efforts to contain it, the spill reached Lake Ontario — a source of drinking water for 9 million people.

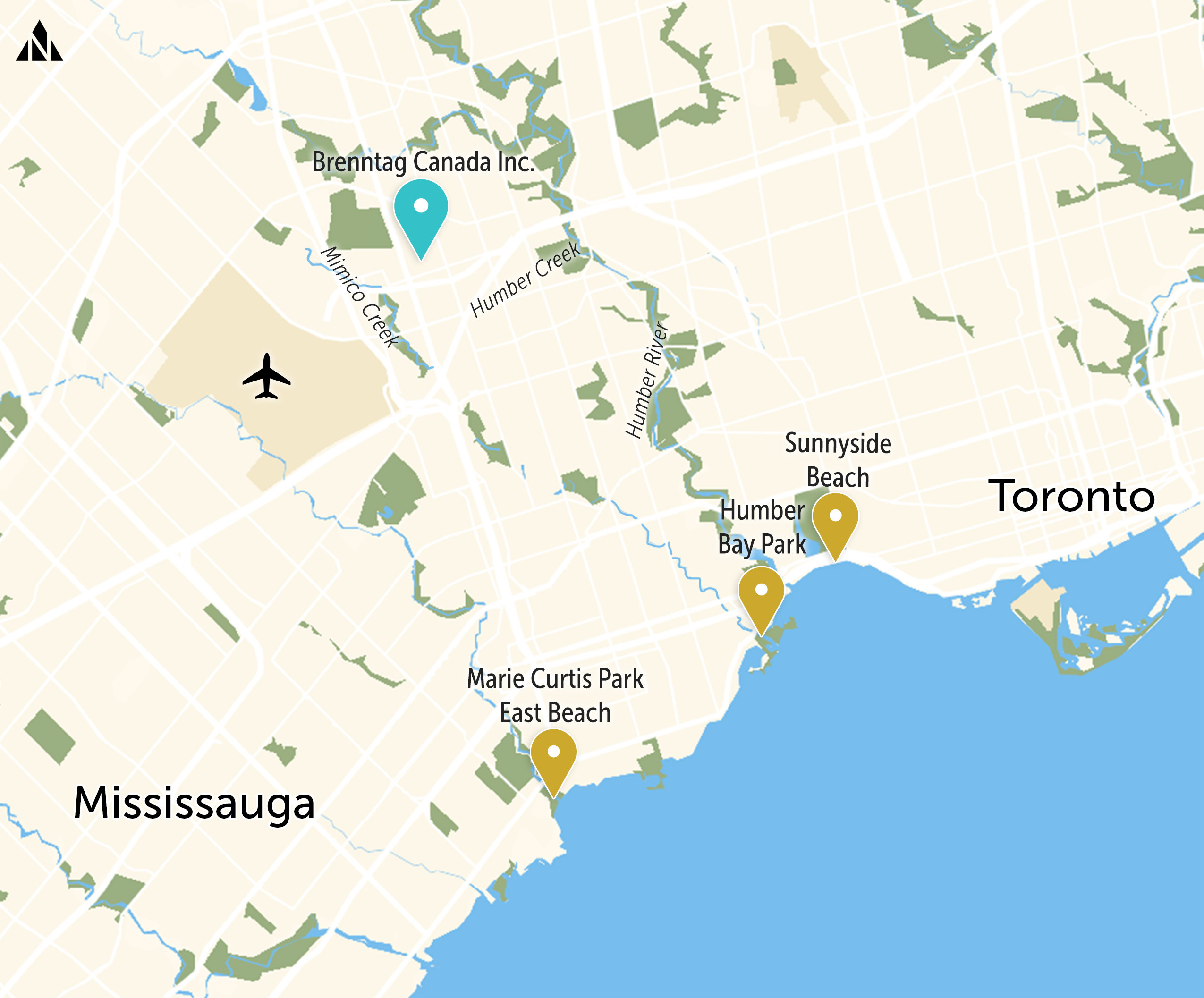

The spill started on Aug. 11, 2023, after a massive fire broke out at a facility in northwest Toronto owned by chemical distributor Brenntag Canada. It took firefighters several days and huge amounts of water and firefighting foam to douse the flames. Within hours, contaminated runoff from the site — an oily brown sludge — started flowing into sewers and then Mimico and Humber creeks, the latter a tributary feeding into the larger Humber River. Both the river and Mimico Creek flow into Lake Ontario.

Through an internal provincial spill report and a second document that was made public by the ministry last November, The Narwhal has pieced together how that slurry made its way 12 kilometres downstream to the lake.

Incident reports are prepared by staff at the Environment Ministry’s Spills Action Centre, a 24-7 hotline that takes reports of chemical spills and keeps records of how they’re contained and cleaned up. The Narwhal accessed the report through freedom of information legislation.

The reports aren’t a perfect picture of everything that happens in response to a spill, but they do offer a window into how different governments react, and the steps taken to clean up an environmental mess.

In the case of the Brenntag fire and ensuing contamination, that snapshot shows how the efforts of hundreds of people — from Brenntag, to their contractors to all levels of government — worked to ensure the damage from the spill wasn’t as bad as it could have been. It also shows instances where some agencies made mistakes, or were slow or unable to respond, causing delays and problems.

Under Ontario law, companies who spill — in this case, Brenntag, which hired contractor GFL Environmental to conduct the work on its behalf — are responsible for the cleanup. The provincial Environment Ministry is responsible for overseeing the process and stepping in if needed. The ministry declined to answer questions about the incident from The Narwhal, including whether it issued any fines or penalties to any of the entities involved in the spill cleanup.

Here’s a look at some of the problems highlighted in the province’s incident report.

Problems in the cleanup of the spill from the Brenntag fire started on the first day, when the Environment Ministry told GFL to install booms and hay-bales along Humber Creek to soak up oil and keep it from flowing downstream. “GFL admitted to forgetting and is currently arranging crews to attend,” the incident report reads.

Later, on Aug. 17, 2023, the incident report says members of the public complained to the ministry about “hydrocarbon sludge” that GFL spilled on the ground at Echo Valley Park, one of several public parks along Mimico Creek where crews staged cleanup work. “GFL is aware of spillage of sludge to roadway,” the incident report reads, adding that the company planned to clean it up the next morning.

And when rain fell on the night of Aug. 18 — a “moderate” weather event, according to the ministry’s public November 2023 report on the spill, and one that had been forecast for days — it was the booms installed by GFL along Mimico Creek that breached, allowing oil to reach Lake Ontario, according to the incident report.

The report doesn’t shed light on what caused the booms to give out. GFL didn’t answer emails and a voicemail from The Narwhal. The Environment Ministry didn’t answer questions about how it checked that GFL’s work was sufficient.

Ashley Wallis, an associate director at the charity Environmental Defence, who has pushed for transparency about the Brenntag spill, told The Narwhal crews should have been able to come up with containment measures that can withstand rain. “I think that’s quite shameful,” she said, adding that similar storms are pretty typical for Toronto in August.

The following morning, ministry environmental officers were on site at Humber Bay Park, where Mimico Creek meets the lake. They recorded their sightings of the oily plume in the water — and they also saw GFL failing to uphold one more commitment, the report says.

According to the incident report, the company had pledged to have three trucks on site at Humber Bay Park at all times to vacuum up contaminated muck. But it only had one, which was sitting idle, according to the incident report.

One officer emailed the company on Aug. 19 to remind them to “take more action at this critical time,” the incident report says. “It was critical that the oil behind the booms remain contained and removed ASAP at[sic] there was a risk that a rain event would cause the oil to be discharged into the lake.”

GFL president Patrick Dolvigi, who is listed as the media contact on the company’s website, didn’t respond to detailed questions from The Narwhal about the ministry’s version of events, documented in the report.

Brenntag didn’t directly answer when asked if the company was satisfied with GFL’s work on the spill, but in an email, spokesperson Robert Reitze said GFL’s crews worked around the clock in the wake of the incident.

“The cleanup work along the creeks and lakeshore was always responsive to changing conditions,” Reitze wrote.

On Aug. 15, 2023, four days after the spill started, Toronto Water — a department of the City of Toronto that’s responsible for drinking water, stormwater and sewage — also failed to do what the Environment Ministry instructed it to, according to the incident report.

Toronto Water was supposed to help install dams to contain the sludge on Humber Creek. But ministry staff reported back that this hadn’t happened, allowing the contamination to move farther downstream. “The two dams that were requested had not been started,” the incident report says. “It is evident that Toronto Water is failing to do the things they were directed to do.”

Later that day, the ministry removed Toronto Water from its duties on Humber Creek and asked GFL to step in. GFL was able to complete the dams in the end, which helped prevent oil from spilling from the creek into the Humber River during the rainstorm on Aug. 18.

In the days immediately following the Brenntag fire, the Environment Ministry called on Toronto Police Services twice for help controlling traffic that was getting in the way of cleanup crews.

The first time, Toronto police told the ministry they were too busy to assist. The second time, police put the ministry staffer who called on hold. That staffer hung up after 15 minutes, and the incident report doesn’t mention the police again.

Toronto police spokesperson Stephanie Sayer said the service received more than 6,500 calls for help the day of the Spills Action Centre’s first call, making it busier than average.

“Although we strive to assist our partner agencies when requested, responding to urgent policing calls takes priority, and we are receiving and attending more emergency calls than ever before,” Sayer said.

On Aug. 19, 2023, a Saturday morning, the Spills Action Centre had to get assistance from Toronto Parks and Recreation to block off parts of Humber Bay Park, where a farmers’ market was set up in the main parking lot. It was the day after oil from the spill hit Lake Ontario, and efforts to vacuum up contaminated muck were well underway.

Crews trying to get out on the water to gather up globs of the oil also found themselves sharing the park’s launch with recreational boaters, despite GFL telling people not to use it, according to the incident report. At one point, people also parked all around GFL’s equipment, blocking workers from getting to it.

“GFL is seeking a direct/backdoor number for City of Toronto Parks, to close the Humber Bay Park, as there is all types of traffic in the park at this time that is hindering the cleanup,” the incident report says.

The incident report doesn’t detail how the situation was resolved, and the City of Toronto didn’t answer questions about what happened and why it didn’t proactively close the park once it learned of the spill.

The day the spill reached Lake Ontario, the Spills Action Centre also tried to get help from the Canadian Coast Guard, which has a mandate to respond to pollution on Canadian waters.

The Coast Guard employee who took the call, a response specialist based several hours away in Sarnia, Ont., told the ministry it would have to submit a written request for help and that the matter was “above her pay grade,” the provincial incident report says.

“We were hoping for a more timely response,” the Spills Action Centre employee responded. The Coast Guard’s “resources were kind of scattered and a field response would possibly take some time to coordinate,” according to the incident report. In the end, the ministry didn’t submit a formal request for the Coast Guard’s help.

Jeremy Hennessy, a spokesperson for the Canadian Coast Guard, said in an email that the agency’s resources are only scattered in the sense that they’re “located across the province, but not in a disorganized state.”

The Coast Guard doesn’t have staff who can respond to environmental hazards in the Toronto area. The nearest staff and equipment are located at bases on Lake Huron or the St. Lawrence River. “Travel to the Toronto area from any of these locations would take a few hours,” Hennessy said, adding that local fire departments and chemical-handling facilities are often better positioned to respond.

“It’s important to remember, like all first responders, we cannot be everywhere at once,” Hennessy said.

Hennessy also said the Coast Guard was told the Mimico Creek spill originated on land, and therefore, was outside of the agency’s mandate.

“The Canadian Coast Guard confirmed it would provide assistance to the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks if a request were made,” he said.

“No further action was taken, as the incident was not within its mandate and no request for assistance was received … As it currently stands — as it did on Aug. 18, 2023 — the Canadian Coast Guard is in a strong position to help.”

Nearly a year after the spill, Mimico Creek appears to be mostly back to normal. The globs of sludge and containment booms are long gone, and water birds like ducks and herons can be seen in the water at Humber Bay Park.

Brenntag says its cleanup work was finished on Dec. 8, 2023, and the company is now moving ahead with a restoration plan.

The Environment Ministry didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal about the status of the cleanup, and it’s unclear whether it’s even possible for crews to remove all of the contamination in Humber and Mimico creeks and Lake Ontario. However, in its November 2023 report, the ministry says it plans to do testing and visual observations to confirm the results of the cleanup. Monitoring at the site will continue into 2025, the report says.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits