In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Clouds hang low over the hills and a sporadic, warm rain slicks the docks at the Pacific Gateway Marina in Port Renfrew.

It should be a good day for anglers around the small southern Vancouver Island community, which advertises sports fishing as its specialty, attracting British Columbians and tourists from around the world who want to catch salmon and halibut.

But, despite the impending long weekend that would normally see anglers flocking to Port Renfrew, more than half the marina’s slips are empty and the remainder are occupied by charter boats sitting idle, unused fishing rods pointing skywards.

In April, after most spring and summer fishing charter and local accommodation bookings had been made, Fisheries and Oceans Canada announced sweeping restrictions to commercial and recreational Chinook salmon fisheries around B.C.’s south coast due to plummeting stocks.

“Chinook are the driving force here,” explains John Wells, owner of Port Renfrew’s Hindsight Fishing Charter.

“It’s a daily income for the town … This has a ripple effect on everyone from sports stores to the marina operators,” he says.

“We rely on this. It’s our town and our livelihood and we care about this and we don’t want to lose it.”

Fishing rods sit idle at the Pacific Gateway Marina in Port Renfrew, following new federal restrictions on Chinook fishing. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The changes mean that Chinook caught this summer must be released and the total annual limit has been reduced from 30 to 10 Chinook per person. The commercial Chinook fishery is also closed until August 20

instead of opening in June as it usually does.

The restrictions are part of a federal government effort to reverse drastic declines in Fraser River Chinook populations and make more fish available for endangered southern resident killer whales, whose preferred diet is Chinook.

But they’ve left Port Renfrew, a village of 150, struggling to reinvent itself after earning a reputation as the fishing capital of southern Vancouver Island, with “some of the best salmon and halibut fishing in North America,” according to the town’s website.

Crab traps are a common sight on the weathered docks of the Pacific Gateway Marina in Port Renfrew. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Locals call this the Marge Simpson Rock. The waters around the rock have traditionally been a favourite fishing spot for Chinook. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Sports fishing for other species remains open, but the large Chinook are the lifeblood of the industry, and, in Port Renfrew, charter cancellations started immediately after the announcement, with customers making it clear they did not want to pay thousands of dollars to go home without a salmon.

A survey of 364 businesses and companies, 82 per cent of which are linked to the fishing industry, conducted for a coalition of 17 Vancouver Island chambers of commerce, found 71 per cent had cancellations after the Chinook restrictions, with 22 per cent saying bookings were down by more than 50 per cent.

A total of 96 per cent said they are losing customers and clients, with 37 per cent expecting to lay off staff and 27 per cent saying they will have to close their business this season or next.

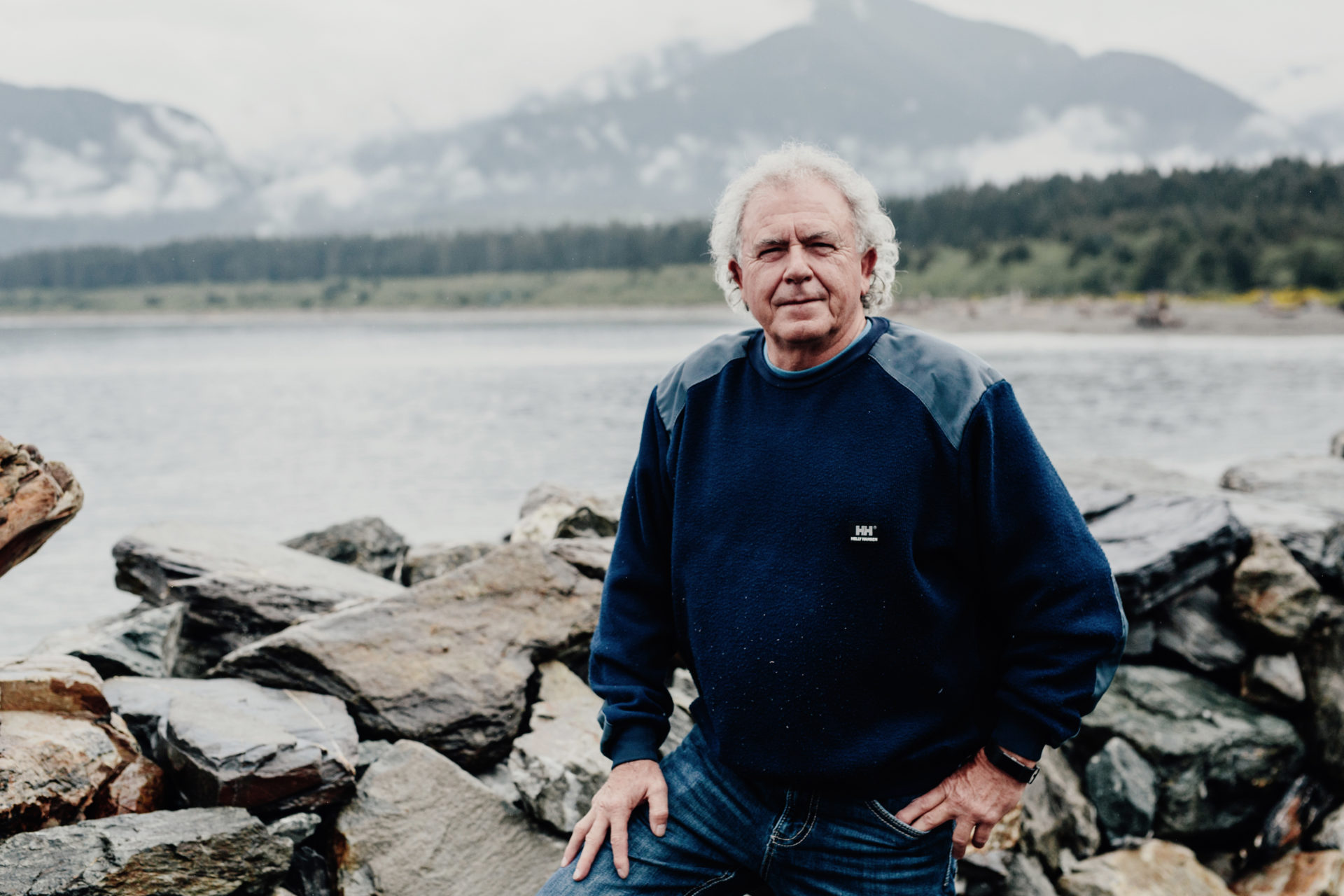

Dan Quigley (left) is a director of the Port Renfrew Chamber of Commerce who has been fishing in the area for 40 years. Quigley heads out on the water with Nolan Fisher but they won’t be bringing home Chinook due to new rules that aim to help save diminishing stocks. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Boat owners are now scrambling to explain that catch and release provides a great West Coast fishing experience, even if the fish must be returned to the ocean, and that other species also provide good sport.

But Alberta resident Jean Pigeon, throwing lines off the marina dock after returning from a guided fishing trip, says he and his friends will not pay for a fishing trip if they can’t take fish home with them.

“We almost cancelled the trip when we got the information that we couldn’t get Chinook,” Pigeon tells The Narwhal.

The group was told that fishing for species such as halibut and ling cod remains open and there are areas further afield (and more expensive to reach) where Chinook can be retained, meaning the trio is returning to Alberta with Chinook and halibut.

Port Renfrew attracts visitors from around the world. These fishermen from Alberta and Quebec almost cancelled their trip because of confusion over new fishing rules that mean Chinook caught this summer must be released. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

On the water near Port Renfrew, conversations revolve around the restrictions. Some such as Nolan and Sandy Fisher, who, enticed by good fishing, built a waterfront home in Port Renfrew, say they are satisfied to catch other species, even though they feel the federal government should be looking at bigger issues such as fish farms and cruise ships.

“I love halibut and cod and maybe we’ll get more mussels and cod,” says Sandy Fisher.

As Nolan Fisher manoeuvres his boat around the inlet, the depth sounder shows shoals of fish. “They are probably Chinook which means we could catch them, but we have to let them go,” he says wistfully.

Port Renfrew resident Sandra Fisher misses catching Chinook but says she is content fishing for halibut and cod. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Few dispute that Fraser River Chinook are in trouble, but, in a community where so many livelihoods are linked to recreational fishing, there is a visceral distrust of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and a general belief that anglers are being singled out as easy targets.

Sports fishermen say the federal government, instead of paying attention to those living in coastal communities, is listening to environmental groups or fish-farming companies, the latter of which — in a rare point of agreement — are widely believed by both conservation organizations and anglers to be negatively affecting wild runs by spreading sea lice and pathogens.

“The trust with DFO has been broken,” says Dan Quigley, a Port Renfrew Chamber of Commerce director who has been fishing in the area for 40 years. “We had hoped to build some alliances, but they stomped all over that and the communications have not been good.”

Dan Quigley says trust with DFO has been broken. He believes Port Renfrew’s fishing industry can survive if people start thinking differently about fishing. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Members of Port Renfrew’s fishing community believe they are scapegoats for decades of salmon mismanagement even though the province’s recreational fishery catches less than 10 per cent of all salmon species, contributes $1.1 billion to the provincial economy and provides 9,000 jobs.

“We are the low-hanging fruit with government making it look good for the general public,” says Wells, pointing out that, when thousands of SNC-Lavalin jobs were at stake in Quebec, the federal government was anxious to take action, but DFO appears unwilling to save fishing jobs in B.C.

John Wells, owner of Port Renfrew’s Hindsight Fishing Charter, says the Chinook restrictions have had a ripple effect on businesses ranging from sports stores to marina operators. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Charter boat operators say their data shows most Chinook caught in the area are either hatchery stock or U.S. fish.

“Ninety-nine per cent of the Chinook that we intercept are American fish,” says Brent Story of Pacific Pro Charters, who says he’s seen a 20 per cent drop in bookings, forcing him to put business expansion plans on hold.

“We know what rivers the fish are from and have the data to back it up.” he says.

But data can be collected in several ways and Greg Taylor, fisheries advisor with Watershed Watch — a science-based charity that advocates for the conservation of B.C.’s wild salmon — says data used by charter boat operators looks at the catch across 12 months instead of the critical months when endangered stocks are passing through the area.

“The science is provided by DFO based on DNA. [Charter boat operators] actually have a significant impact on the stocks of concern — the spring and summer chinook that are endangered — when those fish are migrating through their fishery,” says Taylor, who spent 30 years in the commercial fishing industry and is a member of the marine conservation caucus, a group of nine conservation organizations mandated to provide advice to DFO.

“They are intercepting a significant proportion of those fish that are passing through in the months of May, June and July,” he says.

An added concern is the mortality rate of fish that are caught and released. While DFO estimates that 15 per cent do not survive, a recently released paper puts the mortality rates much higher, Taylor says, adding he would like to see a complete closure of chinook fishing during the critical months.

But the hard truth is that populations of Pacific salmon are shrinking and it is unlikely that the glory days of sports fishing will return in the foreseeable future.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has found that 12 out of 13 Fraser River Chinook populations are at risk. Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, announcing the restrictions, said stocks must not knowingly be put on the path to extinction.

“The science is clear: Pacific Chinook salmon are in a critical state. Without immediate action, this species could be lost forever,” Wilkinson said.

Hammond Rocks at the edge of Port Renfrew’s bay has traditionally been a rich fishing spot for Chinook. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The ‘dragon’ of Port Renfrew. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Quigley is one of a group of businessmen and residents leading a push to look for new directions for Port Renfrew. While he believes the fishing industry can survive if, in part, people start thinking differently about fishing, he says new strategies are needed to keep tourists in the area.

“Not everyone wants to retain a salmon. What they say is ‘the tug is the drug.’ It’s getting the fish on and releasing it. A lot of the guides now have purchased new, rubber-coated nets that help the salmon so they can take a picture of it without harming the fish,” says Quigley, a retired federal administrative judge.

“It’s a new mindset that it’s not just a meat fishery, it’s an experience. Coming out to Renfrew and enjoying the fight with the fish and then letting it go. Seeing some whales and seeing the West Coast Trail and those sorts of things,” he says.

“We’ve got to get the word out that fishing is not closed. It’s far from being closed.”

A fishing boat at the Pacific Gateway Marina in Port Renfrew, a town now striving to re-invent itself. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Paul McFadden, vice president of Mill Bay Marine Group, which built Pacific Gateway Marina four years ago, agrees that a partial solution is changing angler attitudes.

“We don’t have to kill the fish. Look at the Fraser River sturgeon … At the end of the day, it’s time to change the culture of the angler,” McFadden says.

Paul McFadden is vice president of Mill Bay Marine Group, which built Pacific Gateway Marina four years ago as sports fishers flocked to the town. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The need for an economic makeover is a scenario familiar to long-time Port Renfrew residents who’ve lived through booms and busts before.

The first logging camp was built in the area in 1923 and, for decades, industrial logging provided jobs and wealth, but in 1990 Fletcher Challenge moved operations to Cowichan Lake and Port Renfrew started a sometimes painful transition to a tourism and fishing-based economy.

When the Ancient Forest Alliance started a campaign to save massive trees in the area and promote them as a tourist attraction, it was initially greeted with scorn by long-time supporters of the logging industry.

But, with a growing interest in the vital role of old-growth forests, tourists came to Port Renfrew to gaze at massive Douglas fir and spruce trees and awe-inspiring stands such as Avatar Grove.

The community started billing itself as the Tall Tree Capital of Canada and, combined with fishing and hiking, a tourism economy took root.

However, tourists gazing at trees or visiting Botanical Beach tend to come for the day or stay for one night, while anglers stay longer, either taking charter fishing trips or setting up camp for weeks at a time, Quigley says.

Still waters at the Pacific Gateway Marina in Port Renfrew. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Seagulls perch atop rocks at the Pacific Gateway Marina, waiting for the day’s catch to be gutted. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Quigley believes a partial answer to Port Renfrew’s conundrum is for the provincial government to take control of salmon from the federal government, a change he says would provide more opportunities for local input and for pressure to be put on logging companies to restore habitat.

“The B.C. government needs to get it through their heads that these salmon are born in B.C. They are born in our streams and our rivers and they need to take jurisdiction,” Quigley says.

Quigley’s passion for fishing is reflected in wall art at his Port Renfrew home. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Dan Quigley heads downstairs in his West Coast-themed house in Port Renfrew. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Forest clearcut near Port Renfrew, British Columbia. Photo: TJ Watt

The province has not indicated it is interested in wresting control of salmon from the federal government, but Premier John Horgan said after the restrictions were announced that he was disappointed that “years of bad decisions” have led to the need for such conservation measures and acknowledged there would be a significant impact on communities.

Adam Olsen of the B.C. Green Party agrees B.C.’s wild salmon stocks are crashing because of government policies and he believes the province has played a role.

“For decades the federal government has mismanaged the salmon harvest while the provincial government has mismanaged land-based resource harvesting and now we are paying the consequences,” Olsen wrote in his blog.

Despite the obvious need for regulation, the salmon harvest has continued as if it was the Wild West. Instead of conservation measures being rolled out over the last decade, they were dropped on fishing communities just before this fishing season, devastating coastal communities, he wrote.

DFO spokeswoman Lara Sloan said in an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal that there was consultation about the restrictions and, in February, DFO circulated a letter outlining the need for new management actions for Fraser River Chinook because of the fall assessments

and poor 2018 returns.

Restrictions needed to be put in place in April to protect early migrations of the endangered Chinook, Sloan said.

From the fishing guides’ point of view, one of the latest slights from DFO was a decision not to fund applications for Chinook hatchery projects, even though the Sport Fishing Institute of B.C. is advocating to protect wild fish by moving the harvest away from threatened stocks and on to hatchery fish.

Sloan said the department is funding new hatchery conservation measures on at least three low-abundance stocks of Fraser River Chinook and additional use of hatcheries may be considered, but would require careful planning and evaluation.

“The ratio of hatchery-produced fish to wild fish on spawning grounds would need to be monitored to ensure genetic diversity is maintained and potential competition with wild stocks would need to be considered,” she said.

Aaron Hill, executive director of Watershed Watch, says hatcheries are needed in extreme circumstances to keep populations from going extinct, but there is growing scientific evidence they present a risk to wild populations.

“They lower the genetic fitness of the wild populations. They are genetically inferior because they haven’t undergone natural selection and then they interbreed with the wild fish and lower their viability,” Hill says, adding that hatchery runs mean increased fishing and wild fish are then caught as bycatch.

“They also compete with wild fish for food and there’s increasing evidence that that is having a substantial impact on some populations. It’s an increasing concern with climate change because the warming ocean conditions are reducing the quantity and quality of food available for salmon in the ocean,” he says.

Watershed Watch is asking the federal government to put all new and existing hatcheries through a full biological risk assessment.

“There are conservation benefits to hatcheries, but, if you are just putting those fish out there to catch, it’s not providing a conservation benefit, it’s providing a fishing benefit that might be detrimental,” Hill says.

A lone charter boat fishing in a regulated area far from Port Renfrew. A charter this far out could cost the operator up to $250 in diesel a day. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Another touchy topic for many Port Renfrew fishermen are First Nations Chinook net fisheries on the Fraser, which boat owners say are pushing a wedge between communities as they are sidelined while fish heading for spawning grounds are intercepted.

“They should be letting those fish get up the river,” Wells says.

However, Sloan said First Nations openings are limited, accounting for approximately five per cent of returns, and must be allowed to meet constitutionally protected rights to harvest small numbers of Chinook for food, social and ceremonial purposes.

Under the constitution, conservation is the first priority, followed by First Nations fisheries, with commercial and recreational fisheries taking third place. Any deviation would likely spark a lawsuit against the federal government.

Murray Ned, executive director of the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance, which represents Indigenous communities along the river, says conservation is of prime importance and full communal fisheries are not being conducted this year.

The federal government does give permission for small ceremonial fisheries when a community member dies, in which case about three salmon are taken to feed people at the funeral, or for historical ceremonies honouring the return of the Chinook.

“It is only one person going out for about eight hours to try and capture those fish,” he says.

The Chamber of Commerce and a new opportunities committee is working with Pacheedaht First Nation on strategies ranging from ecotourism, with fishing guides running trips to view wildlife such as bears and cougars, to promoting Port Renfrew as the new West Coast mountain bike capital.

“Everyone wants to compare us to the next Tofino, but I think we can do much better than that. Our mountains are higher and we have one of the most gorgeous beaches on the planet and wonderful campsites,” McFadden says.

Mountain biking, one of the major growth industries, offers huge opportunities, he points out.

“We can offer trails of 385 kilometres in three different directions and we have the most frost-free days in Canada.”

That optimism is echoed by Karl Ablack, vice-president of Port Renfrew Chamber of Commerce, who heads Port Renfrew Management, which owns about 175 hectares in the area.

Ablack envisages a new town centre, surrounded by affordable housing and a multitude of tourism opportunities.

“There is definitely short-term pain … but it now gives us a reason to be talking about diversification and not relying on one industry like fishing and logging,” he says.

Taylor of Watershed Watch points out that “it took a long time to get in this terrible position and it’s going to take us a long time to get out.”

“There’s no easy answer, there’s no magic bullet,” he says. “It’s not killing seals or enhancing fish.”

“The most important, immediate solution we can have is to identify those populations of Fraser River chinook that are classified as endangered and stop killing them.”

Updated June 18, 2019, at 3:12 p.m.: The article originally stated Alberta fishermen were told they could fish for red snapper. The article has been updated to reflect the fact red snapper can not currently be retained.