Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

By the First World War, coal mining was booming in Alberta. The small town of Nordegg boomed right along with it.

The town, on the eastern slope of the Rockies, was a flourishing mining hub — it had a hospital, churches, stores, homes and a red-light district.

But booms don’t last forever.

By the 1950s, everyone in Nordegg was packing up and leaving. The advent of diesel-powered train engines had reduced demand for coal. The mine closed, workers were out of a job and people uprooted their families to look for work elsewhere.

Nordegg became a ghost town.

Fast forward a few decades, and Alberta’s coal mine workers are again facing a categoric change. It’s not the first — or the last — time that resource workers find themselves suddenly out of a job, struggling to figure out what’s next.

This time, Alberta’s long reliance on coal-fired electricity is on the chopping block — and government, unions and communities are grappling to understand what a “just transition” really means.

The coal-fired Sundance Power Station is 70 kilometres west of Edmonton in Wabamun, Alberta. Wabamun Lake is one of Alberta’s most heavily used lakes for recreation. Wabamun is a Cree word for mirror. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Today, Alberta produces more coal pollution than the rest of Canada combined.

Or, rather, it does for now.

Coal-fired power is the main source of electricity in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, but rules introduced by the provincial and federal governments have set a deadline to wind down the industry.

Under the new rules, all coal-fired power plants in Alberta will be shuttered by 2029 — and with those will go the mines that dig up the type of coal, known as “thermal” coal, that fuel them.

Many companies — to the initial surprise of workers — have elected to shutter their operations (or switch them to natural gas, which requires far fewer employees) even sooner. Layoffs are already occurring.

The collapse of industries is nothing new. Some 35,000 people lost their jobs when Newfoundland’s cod fishery collapsed in the early 90s. The Luddites were originally a group of British weavers and textile workers who protested losing their jobs to machines. There are no longer elevator operators, lamplighters or telegraphists.

And soon, in Alberta, there will be no more coal-fired electricity. And that means some 2,000 people working in the industry will be out of a job.

The Narwhal met with coal miners from the Highvale Mine — owned by TransAlta — near Wabamun at their union hall to talk about the transition. Their feelings about the coming end to their livelihood as they know it were varied — some were planning to access programs set up by the Government of Alberta to help them make the transition to new jobs, others were terrified about what they’ll do next or whether they’ll have to move or work out of town.

Coal mining first began in Wabamun in the early 20th century. There are three mines in the region, including the Highvale Mine, the largest strip mine in Canada. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

As one miner — fearful of having to seek work out of town — put it, “[My kids] say ‘where are you going to go, dad? I don’t want you to leave, dad.’ What do I tell my kids?”

“I honestly don’t know what to say to them.”

The question of how to support workers in an industry that’s winding down is a big one as the world undergoes what economist Jeremy Rifkin calls the Third Industrial Revolution. Workers reluctant to settle for jobs that pay less than their current positions are finding themselves in a tricky position, as the government grapples with the level of support owed to those who have made their living off an extractive industry — an industry they thought would last at least as long as their careers.

But as it turns out, it will be over a whole lot sooner than that.

The United Steelworkers Local 1595 gathers in a hall on Main Street in the village of Wabamun, population 682. The hall is between the credit union and the grocery store, across from the bottle depot. The village office is just down the road. The road ends abruptly to the south, and the glassy surface of Lake Wabamun occupies the bulk of the horizon, along with the stacks of coal-fired power plants on the opposite shore.

Inside the hall, there are samples of coal — lacquered so they’re not dusty to the touch — and memorabilia from coal-mining days of yore. Posters advertise safety in the workplace, and a stack of brochures sits on a desk by the computer. “Getting it Right,” they’re titled. “A Just Transition Strategy for Alberta’s Coal Workers.”

As photographer Amber Bracken and I walk in, all heads turn from their laptops to look at us. They’ve had a look at The Narwhal’s website and they want to know: are we environmentalists? As I try to explain the distinction — I’m a journalist who covers energy and environment issues — the local’s president assures us that it’s no matter either way.

“We’re a diverse group,” he says, laughing. It’s not long before we’re being offered coffee and lunch.

There’s no denying the collective spirit as the members gather for a meeting. 47-year-old Martin Tinney is in the hall’s kitchen, making hamburgers. He laments that he used up the rest of the wild game he brought the night before.

Tinney is an avid hunter — he manages his gun sales business in his free time — and frequently teases his colleague, Len Austin, who is a vegan. Austin laughs and shrugs. This clearly isn’t the first time he’s heard the joke. “I’m probably the only vegan steelworker,” he tells me. He brought vegan spaghetti squash pesto for lunch.

Union pins decorate this cap in a memorabilia display at Local 1595. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Union trustee, Erin Lampreau, said he’s concerned about the long-term health implications of being a miner. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Union executives prepare for executive and committee meetings at the United Steelworkers Local 1595 in Wabamun. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The miners are gathered for a meeting to discuss typical union business — preparing grievances and so on — but a larger issue hangs over all of their discussions. In the not-so-distant future, there won’t be a coal mine and there won’t be any more jobs.

Roy Milne is the local’s president and has worked in the mine since 1983. He’s wearing a clearly identifying shirt — “coalminer and proud to be,” it says in bold black letters in front of a crest of sorts — a coalminer’s helmet, pick and shovel.

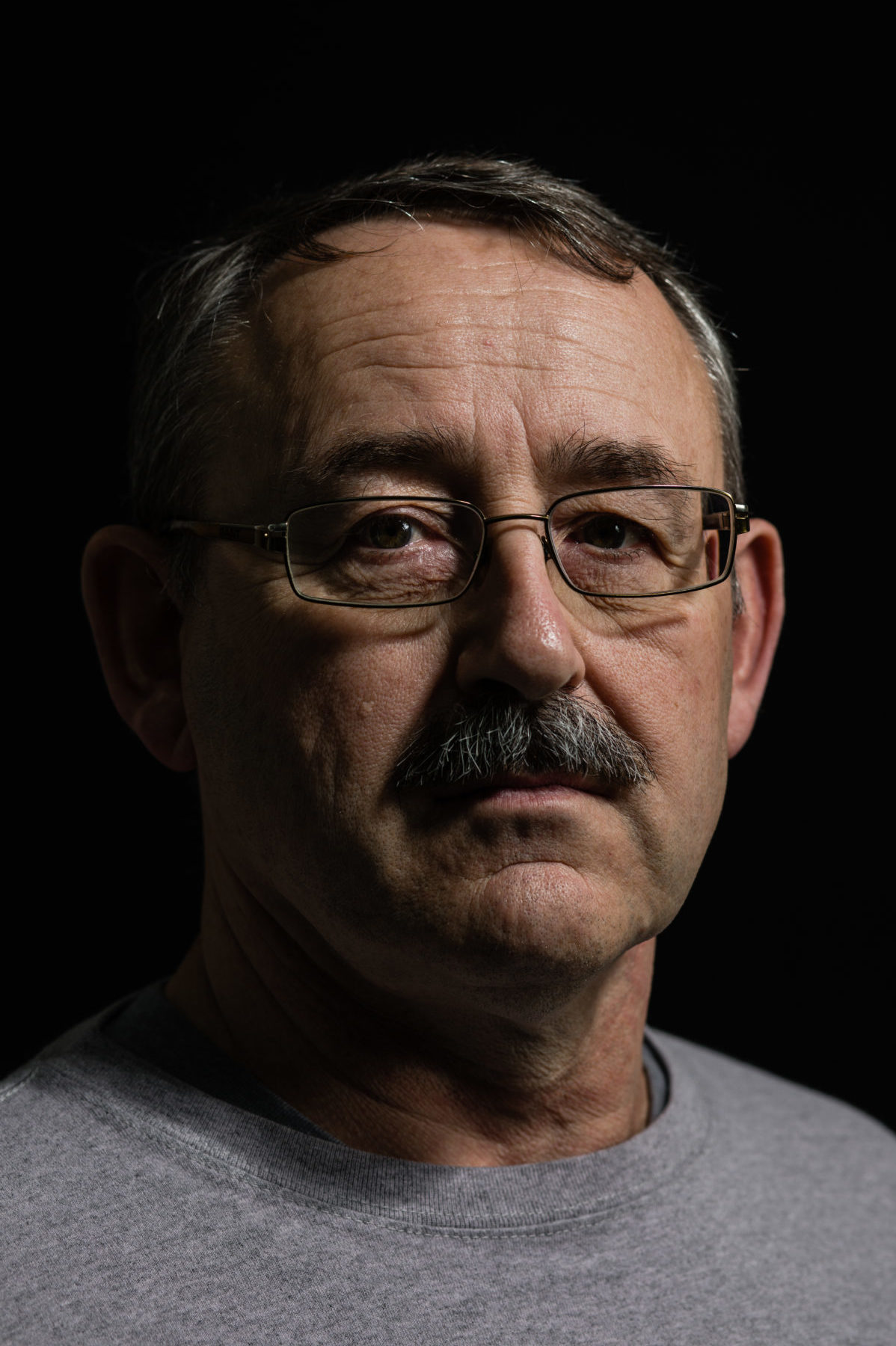

United Steelworkers Local 1595 president and coal handling plant operator, Roy Milne. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Milne, who has worked in the mine since 1983, told The Narwhal there have been “unintended consequences” of Alberta’s coal-powered electricity phaseout. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The government, he says, had “good intentions to clean up the atmosphere and pollution” and “the province has done a good job with the just transition [program].” But he’s concerned about how everything will turn out for coal workers.

“There have been unintended consequences,” he adds.

The transition program Milne is referring to is the Coal Workforce Transition Program, set up by the Government of Alberta — it involves a $40-million fund, funded by the carbon tax, for communities and workers affected by the phase-out.

Former coal miners are eligible for $5,000 to cover moving expenses and up to $12,000 to pay for tuition at a post-secondary school — a boon for those seeking retraining, though many miners told The Narwhal they’re frustrated they’re not eligible for the program until they’ve been officially laid off, making it difficult to prepare for a new job before they receive a pink slip.

Older workers are eligible to receive 75 per cent of their previous earnings during a bridge period between their lay-off date and their retirement, though very few workers meet the criteria.

In a statement, Minister of Labour Christina Gray told The Narwhal, “We know that some workers have had concerns with accessing some these programs, we share their concerns, and we’re working to fix them.”

“We’ve got these workers’ backs and we’re going to keep working to ensure that they get the support the need.”

Mosa (Mo) Marji, left, and Martin Tinney, centre, prepare for their upcoming meeting. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A custom window bar, in the form of a stylized union logo, casts a shadow on the wall at Local 1595. The union’s first collective agreement was signed in 1961. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Laid-off workers are also eligible to receive 75 per cent of their previous earnings while they look for new jobs (other workers who receive employment insurance are paid 55 per cent of their weekly earnings).

But critics say finding a new job isn’t easy in a small community, and one workforce can’t simply be reallocated to a new industry overnight.

Some workers told The Narwhal they felt left behind by their employer, TransAlta — and were upset at what they describe as company’s eager shift to natural gas — and its dramatic reduction in the workforce. TransAlta told The Narwhal it was “unfortunately not able to facilitate a phone interview at this time,” and instead answered questions by e-mail.

The company said it is “committed to treating our employees with dignity and respect,” and acknowledged its workforce will be “much leaner” in the future.

Those coming layoffs are what workers are anticipating, as soon as early 2019.

But according to Waylon Pye of the United Utility Workers’ Association, there’s been “zero uptake” on the program to reimburse moving costs for TransAlta workers who work in coal facilities near Wabamun.

“It is people’s last choice,” he told The Narwhal. “These are the places people live and work, they’ve set their roots there.”

“Moving is a big deal.”

Pye noted that United Utility Workers’ Association has been happy with the NDP government’s response to the coal phase-out. “The government’s done a great job on these programs,” he told The Narwhal. “It’s the best in the country, but no program is perfect.”

The coal-fired Keephills Power Station in Wabamun releases sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and mercury into the environment. Coal-fired power generation releases other harmful pollutants, including lead, cadmium, dioxins and furans, arsenic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

This is not the first time coal miners in Alberta have faced mass layoffs. In the 1950s, thousands of coal miners lost their jobs when a combination of factors reduced the demand for coal — the membership of the western provinces’ division of the United Mine Workers of America dropped from 9,500 in the early 1950s to just 1,625 by the spring of 1961.

At the time, coal-powered steam engines were switching to diesel-powered trains and natural gas was making inroads in the heating market, according to Tom Langford, a sociologist at the University of Calgary. Combined, this meant a dramatic decrease in the demand for thermal coal.

The transition program offered by the government was minimal — provided for by the Coal Miners Rehabilitation Act of 1954 — offering assistance only to miners who found a job elsewhere and needed help with moving expenses. Miners without families, Langford says, were given a bus ticket.

“The provincial government basically said if you can find a job anywhere — between the Great Lakes and the Pacific Ocean — we’ll move you there,” Langford told The Narwhal.

The rapid transition, Langford said, “led to small towns becoming ghost towns.”

Miners and communities expressed concerns at the time that are strikingly similar to those heard across coal-mining communities today. In 1954, a coalminer’s wife wrote a letter to the editor in her local newspaper in Coleman, in the Crowsnest Pass, that could just as easily have been written today.

“Coal mining is our only industry here and way of making a living. How many of us can just pack up and go? How many of us have invested all our money here in Coleman in our homes, provided education for our children, and with the intention of spending the rest of our lives here in the coalmine. Now what?”

Today, the question of “now what?” is heavy on the mind of Martin Tinney. Coal mining is somewhat of a family tradition for Tinney. His dad, his uncles and his cousins have all worked in the mine. His son dreams of being a coal miner when he grows up.

Tinney’s family farm — they raised cattle and grew cereal crops — was right next to the coal mine. “Four generations this land has been in our family…right on the edge of the mine,” he says. “They’d blast all the time and our house would shake…That’s just the way it is.” He still farms land adjacent to the mine, and has worked in the mine for nearly 11 years.

United Steelworkers Local 1595 union treasurer and excavator operator, Martin Tinney at the union hall. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“I have to leave this area. I don’t want to. I don’t want to leave my kids,” Tinney told The Narwhal. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The Keephills Power Station comprises three coal units. Water from the Wabamun Lake watershed is used to cool these units, which burn coal at extremely high temperatures. The process generates steam, which in this photo billows over a nearby pasture. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“I’ve run 30 pieces of equipment at the mine…Anywhere from a little rubber-tire hoe to the big shovels to the big backhoes, the little backhoes, the heavy haulers, all the trucks, wheel dozers, the drills.”

Tinney, like many other miners, thought he had signed up for a job that would carry him through to the end of his career.

“I expected to retire here along with a lot of these guys,” Tinney says. He laments the loss of a good job close to home. “Here’s a job I can be home every night with my kids. I can tuck them in, I can say prayers with them,” he says. “Now that’s coming to a close. Now I have to go — to get that kind of money and full benefits — I have to leave this area. I don’t want to. I don’t want to leave my kids.”

Langford, the sociologist, points out that mines were never intended to operate forever — it’s antithetical to the whole concept. “Across the country, miners face the same problem whenever mines close,” he says.

“Either the product is exhausted or it becomes too difficult or expensive to mine at one site any more — or market conditions change.” The latter, Langford says, is what’s happening in Alberta right now.

This time around, he says, is not all that dissimilar to the decline in thermal coal mining of the 1950s. “Like the dieselization of railway locomotion, now we are switching to a new approach to generating electricity — [this time] for health reasons, pollution reasons, greenhouse gas reasons.”

(According to the Government of Canada, coal was responsible for 75 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions stemming from electricity in 2016. This is a mammoth share of emissions, considering that coal makes up less than nine per cent of the country’s electricity generation.)

A dirt road winds down to the coal-fired Keephills Power Station, five kilometres south of Wabamun Lake. Two of the coal units at Keephills were built in the 1980s. A third, more efficient unit was completed in 2011. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Mineworkers, he says, have always been an “itinerant resource worker group,” reliant on “quick mobility,” when the resource runs out or is no longer profitable to extract.

But, because many of the mines now set to close have been operational for decades, many workers, he says, may have lost that itinerant mindset — and no longer live the nomadic lifestyle of moving with the work, job-to-job, town-to-town.

“It seemed like coal-fired generation would continue forever,” Langford says.

But for many miners, there was a misleading promise of a secure job — and the end is coming far too quickly. The Alberta Federation of Labour has laid out the miners’ concerns:

“The phase-out of coal-fired electricity generation is being justified as a necessary decision to address the serious societal issue of climate change. When addressing a societal issue that will impose costs, it is unfair to download those costs on a single segment of society of individuals, in this case, workers within the coal-fired electricity sector. After all, these workers are not responsible for the emissions and air-quality problems associated with their workplaces.”

Langford supports the Alberta Government’s Coal Workforce Transition Program, noting it’s “a model for this sort of economic change.”

And, he adds, in some ways, “coal is getting a jumpstart on the retraining you need to do in order to have a good job that pays well in this high tech industrial society that we’re already seeing.” After all, with driverless trucks poised to enter mines in a big way, many workers may have been out of a job in the long run in any case.

It’s not just miners who are concerned about the loss of their jobs. The communities that have relied on coal-fired electricity for generations are also wondering what the future holds.

“A third of our population works over there,” says Charlene Smylie, the mayor of Wabamun. “It’s still our main industry and people depend on that.”

“…coal workers aren’t going to open up an ice cream shop.”

One older coal plant has already shut down in Wabamun, she says, and the town saw a 58 per cent decline in tax revenue. Already, she says, people are moving out of the community and there are less students enrolled in the local school.

“If coal’s off the table, we want something to be done for communities and the workers,” Smylie said, adding that the community is grateful for a coal transition grant they received from the Alberta government, for just under $350,000.

Smylie is hopeful that Wabamun can take advantage of the large lake it’s built on, and encourage tourism as a backbone for the local economy.

The conundrum, she says, is that “coal workers aren’t going to open up an ice cream shop.” Those high-paying jobs, she added, just aren’t going to be replaced.

At the union hall, some miners told The Narwhal they’re concerned with the discrepancy between the amount of money available to workers and the amount available to the companies being paid out to shutter their coal-fired operations.

“The government is paying all this money to big companies — our money,” says 59-year-old Mosa (Mo) Marji, who has been an industrial mechanic at the mine for eight years. “We’re paying these guys to get me out of a job.”

Marji is referring to the more than $1 billion over 14 years that the provincial government has committed to paying coal power producers in compensation for ending contracts for coal-fired electricity and as incentives to switch to natural gas.

Austin has similar concerns. “I’m not against companies making money; making a profit,” he says. But, he adds, worker compensation is lopsided.

“Corporations are misusing their power.”

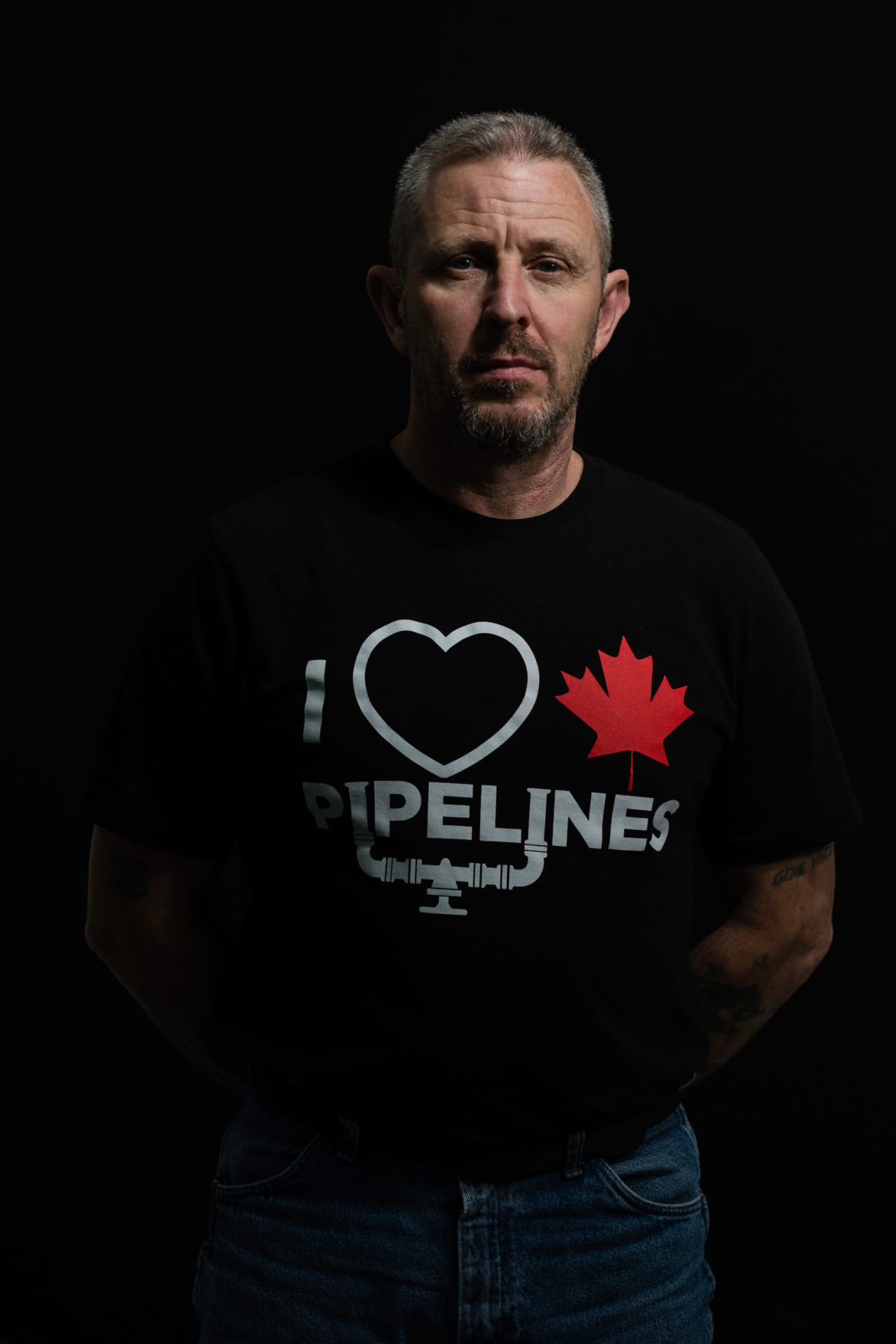

United Steelworkers Local 1595 union executive member and serviceman, Len Austin. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Steam from the Keephills Power Station sweeps across the landscape. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Austin says a lot of his coworkers wonder, “why do we have to sacrifice to be the leaders when our damage is so small?”

“I don’t think it’s necessarily a good thing to rely on what others are doing,” he says. “I can see why we, as a whole, want to get off of [fossil fuels].”

But Austin is adamant that miners shouldn’t be criticized for wanting to keep good-paying jobs. Miners can expect to start at about $26/hour, and quickly jump to $33/hour or more. Certified tradespeople (welders, millwrights, electricians) make $47/hour.

“Miners are making good money, but what the miners are making should be the norm,” says Austin. Minimum wage jobs, even teacher salaries, he adds, are “not sufficient.”

“I, like a lot of the workers, have a high school education,” he says, but working at the mine has piqued his interest in labour rights. Now that his job is coming to an end, he’s planning to access the Government of Alberta’s tuition voucher program — ideally, he wants to go back to school to study labour law.

“I became more committed and passionate about the labour movement. The ideas of labour rights became more important to me.”

Austin is speaking to heart of the issue top of mind for many miners. With little education, can they ever expect to make the same salary again?

Debbie Labrecque, 50, thought for sure she’d retire at the mine. “I never thought I’d leave,” she told The Narwhal.

Labrecque started at the mine 14 years ago — she’s a heavy equipment operator. “As a woman, we’re kind of held back on our wages,” she says of her decision to leave her office job and work as one of the few women at the mine.

“This was an opportunity to make as much as the men.”

She ended up meeting her now-husband, Mike, at the mine. He’s been at the mine for 12 years, and like many others, never finished high school. “Way back in the day you didn’t need your high school diploma,” Labrecque explains. “So he went straight into mining.”

Getting his GED, the equivalent to a high school diploma for adult learners, is now “on his bucket list,” says Labrecque.

Debbie Labrecque. “I’m middle aged, I’m 50, so I’m not as employable as most,” she told The Narwhal. Photo: Alberta Federation of Labour Staff

As for herself, she’s not sure. “I’ll probably get something a little more stable…a more mundane, boring lifestyle,” she says, laughing. “I’m middle aged, I’m 50, so I’m not as employable as most.”

“Me, at my age?” she says. “I really don’t want to go back to school full-time. Like, oh my gosh.”

Either way, she says, “the biggest concern [about finding a new job] is the money.”

“As a woman I’m not going to make the money I’m making here.”

Erin Lampreau didn’t finish high school either.

“My thought was you go to school so you get a good job,” he says, “but I thought ‘I’ve got a good job.’ ” Lampreau got a job in the oilpatch when he was a teenager. His story is not unfamiliar in Alberta, where many young people go straight into high-paying resource-sector jobs.

Lampreau is a heavy equipment operator in the mine — he’s been operating large trucks that are “about the size of a house,” since 2010. “I thought for sure I’d retire at the mine,” he says.

When he first heard about the coal phase-out, he was angry, like many of his colleagues. But his attitude has shifted. “I’m looking forward to the change,” he says. “This is a chance to get out of the only industry I’ve really been in.” Lampreau has been considering accessing the government’s tuition vouchers program and studying at NAIT to become a mechanic, which he hopes will be “more of a challenge.”

In the meantime, he’s working in his time off to try to finish his GED.

Lampreau isn’t just thinking about what job he might get in the future. He’s also worried about the potential health effects of his job, especially once he’s laid off and no longer has access to employer health benefits. “It’s not just a job and a pay cheque,” he says. “It’s your health.”

As a miner, Lampreau undergoes regular respiratory checks through his employer, and he’s concerned about what will happen when that monitoring stops. “As a miner, definitely it’s something I know is going to affect me later on down the road…[I’m] frightened to know I may get sick and not have anywhere to go…without any recourse.”

United Steelworkers Local 1595 union trustee and rescue team captain, Erin Lampreau. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“I’m looking forward to the change,” Lampreau told The Narwhal. “This is a chance to get out of the only industry I’ve really been in.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Many of Lampreau’s colleagues disagree, and told The Narwhal they are not at all concerned with their health, pointing to improvements made over the years in technology to clean up what comes out of the stacks.

Burning coal has been linked to a slew of human health concerns, including asthma and other respiratory ailments, neurological problems, cancer, heart failure and cardiac arrest, among others issues.

“I like my job but I also know that it’s really harmful.”

According to the Pembina Institute, phasing out of coal-fired power by 2030 will mean 1,008 fewer premature deaths in Canada between 2015 and 2035 — the vast majority of which are attributed to the Prairies — and 871 fewer visits to the emergency room.

“I like my job but I also know that it’s really harmful,” Lampreau says. He’s rueful that his work is seen as contributing to environmental degradation, but he does think it’s a problem. “Obviously, as a coal miner… I’m polluting every day, every time I load coal into the plant.”

“[Coal] is dirty,” he says, while also expressing support for technologies at newer facilities. “It’s a pollutant. I don’t want that for my grandkids.”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, coal-fired power plants are a major source of fine particulate matter, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, ground-level ozone and heavy metals like mercury — long-term exposure to the latter can cause respiratory issues or problems with the development of children’s nervous systems.

Coal-fired power is the source of 37 per cent of Alberta’s mercury emissions and more than 40 per cent of provincial sulphur dioxide emission, which is a major air pollutant and has been linked to possible increases in mortality with long-term exposure (short-term exposure to high levels can also be life threatening).

Some miners point to newer facilities as evidence that the industry has the potential to operate in a cleaner way, a point Pembina also acknowledges: “Newer coal units…are equipped with pollution control technology for [sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides] that significantly reduces these pollutants.”

Instead of paying companies to get rid of coal entirely by 2030, some miners wonder why the government couldn’t invest in technologies to clean up coal mining, and shut down only the older plants first.

For example, at the Keephills 2 facility in Wabamun, TransAlta says 60 per cent of mercury is recovered when coal is burned. And Keephills 3 is one of Canada’s “cleanest coal-fired facilities,” according to TransAlta, which reports greenhouse gas emissions are lower than conventional coal plants — a reduction that the Pembina Institute describes as “slightly less” emissions — and still far more than natural gas or renewables.

Union executive and shop steward, Glen Davies. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Davies grew up in a mining town in Wales. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

According to the Pembina Institute, coal-fired power plants still emit more than twice the carbon pollution per unit of power generated, when compared to natural gas. And new reports have suggested that building new wind and solar projects is cheaper than continuing to run coal plants.

Conflicting messages — “clean coal” on one side and “end coal” on the other clearly led to differing opinions among the miners who spoke with The Narwhal. Some miners voiced concerns about human-caused climate change and advocated for cleaning up pollution — while others felt very differently about coal’s impact on the planet.

Their thoughts on the way forward were also mixed. Several pointed to the idea that Canada is a relatively small user of coal for electricity compared to other countries, and wondered why Albertan miners should lose their jobs while coal continued to be used elsewhere.

Many coal workers point to the fact that coal continues to be burned in other parts of the world, including in developed countries. Germany, for example, still produces a quarter of its power from lignite, a type of coal often referred to as one of the dirtiest fossil fuels.

And Australia relies on coal for 60 per cent of its electricity, which many critics of Alberta’s coal phase-out point to as evidence that even the developed world relies heavily on coal for electricity.

The Narwhal spoke with Paul Burke, an economist at the Australian National University, to better understand the situation in Australia. Burke pointed out that while the country still burns coal for electricity, its reliance on coal is declining rapidly — there has been a 26 per cent drop in the share of Australia’s electricity produced by coal since 2001.

“The energy transition is happening quite quickly in Australia, away from coal,” Burke said, noting that 12 coal-fired power stations in Australia have closed since 2010 — and this at the behest of private companies responding to market forces, not government action.

Some of these facilities, Burke noted, closed with only six-months notice to workers and communities, prompting a new rule that requires three-years’ notice before a closure.

Australia isn’t alone in decreasing its reliance on coal power, though other countries are legislating the decline.

Last year, 19 countries, led in part by Canada, agreed to phase out coal — including the United Kingdom, France and Mexico, among others. The South Korean province of Chungnam — which has nearly twice the coal-fired electrical generating capacity of all of Canada — joined the agreement this fall. The Powering Past Coal Alliance now has 75 members, including 47 regional and national governments.

But regardless of the different approaches taken around the world, the provincial and federal governments in Canada have been clear — coal-fired electricity is over.

There’s little doubt that phasing out coal is contentious in Alberta — and there are many mixed feelings about the best way forward. For some, it’s a no-brainer — switch to cleaner sources of energy as soon as possible. Others wonder why smaller steps can’t be taken, why their jobs are on the line.

Mo Marji, one of the coal miners poised to lose his job soon, has mixed feelings himself.

“I value our environment,” he says. “I’m very well aware of climate change and I know what’s going on in the world.” Marji has five grandkids, and he wants to ensure a healthy future for them. “I’d like them to grow up in a world without having to put up with all this pollution and with climate change that’s causing worse storms…I believe man has contributed to that climate change.”

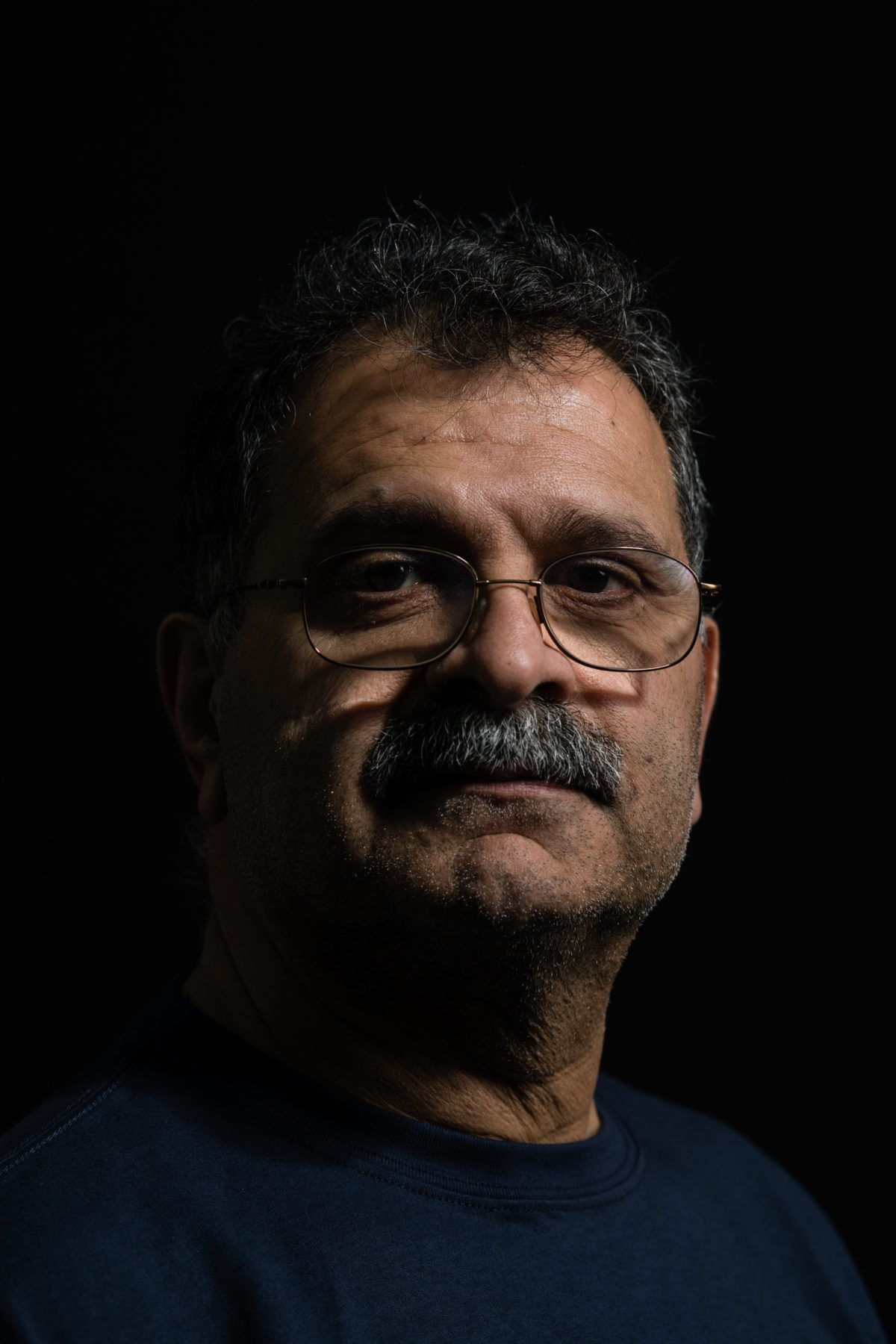

United Steelworkers Local 1595 union trustee and millwright, Mosa (Mo) Marji. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“I’m very well aware of climate change and what’s going on in the world,” Marji told The Narwhal. “I believe man has contributed to [it].” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The sky dims beyond the Keephills Power Station and heavy transmission lines. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

But in his opinion, shutting down coal seems to be more political than effective. “If you’re going to shut down coal, because you’re saying it’s bad for the environment, then ramp up the oilsands and build pipelines to export more oil… how are we helping the environment?” he asks.

He wants to see coal continue to be used, but advocates for investment in improved technology. “If we’re using something that’s polluting our environment, we should try to find the best technology available to clean it up.”

Either way, he’s in the same dilemma as the rest of his coworkers, as coal-fired electricity is on the way out in Canada.

What to do next? Yes, there are jobs in renewable energy, he says — but not in Wabamun, and from what he’s heard, they don’t pay half as well.

Marji is near retirement, so his current idea is to start up a horse-training business on his land, 10 kilometres from the mine, where he lives with his wife. He’d like to run summer horse courses for kids at camp.

Based on his seniority, he estimates he has nine months of work left, maybe a year. “I’m not really sure.”

“If I really want to, I can get another job. I have my tools, I have my certificate.” That’s different from many of his coworkers, he says, who have worked in the mine all their lives.

It’s them he’s really worried about.

Editor’s note, June 2019: Some links to Government of Alberta websites in this article were updated to reflect changes to the government website that were made following the election of the United Conservative Party in April 2019. In instances when content on the government’s websites changed substantially, archived links have been substituted, using the Wayback Machine.