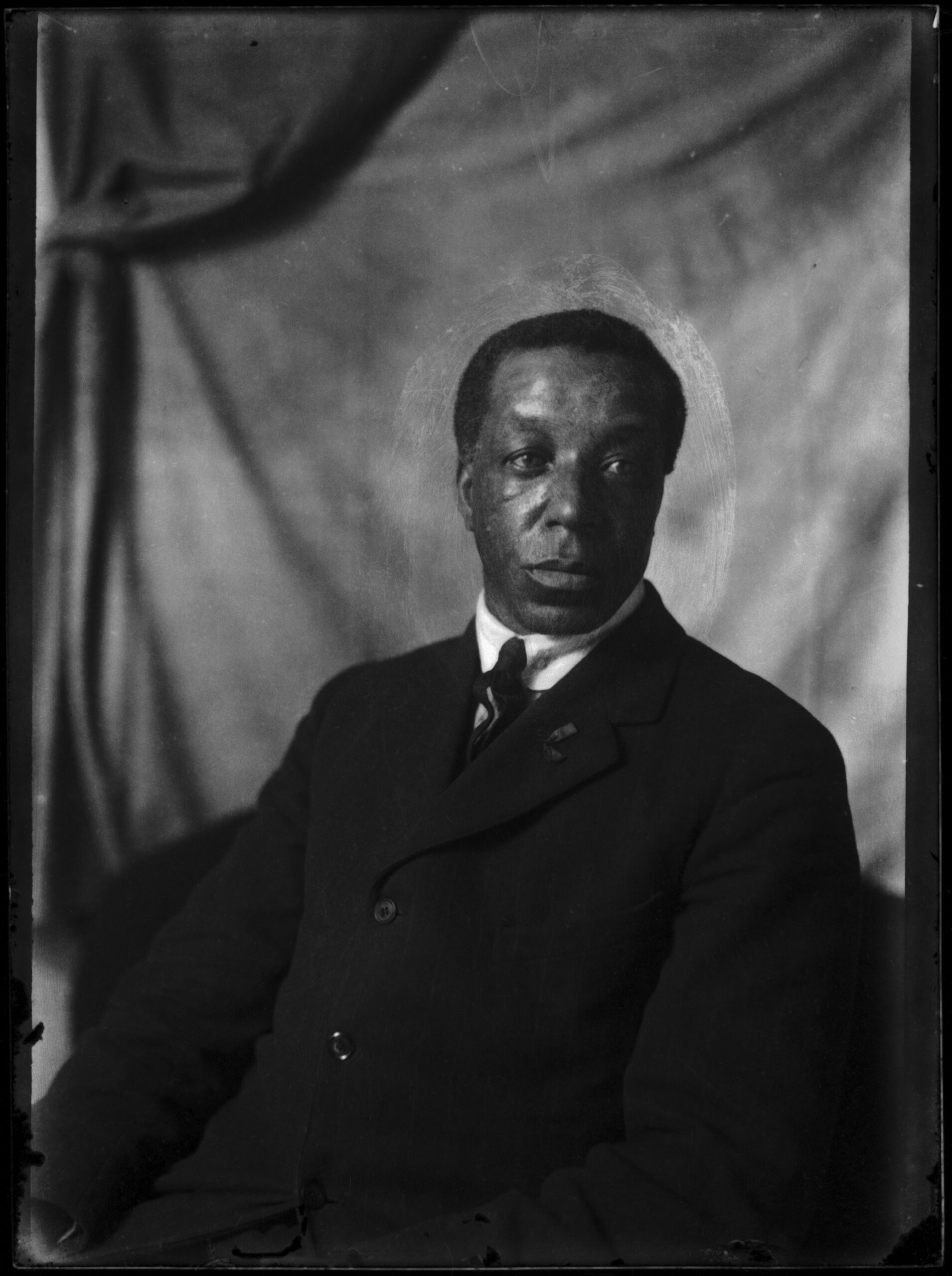

There’s something unmistakably legendary about Billy Beal to those living in the forestry and agricultural communities of Manitoba’s Swan River Valley.

He was something of a renaissance man: an engineer by trade, but in the everyday struggle of homesteading in Manitoba’s northwest, he moonlighted as a doctor’s assistant, mechanic, astronomer, carpenter, librarian and school district representative.

Just about everyone in Swan River remembers a story about Beal — or knows someone who does.

“His sense of community was just so strong,” Robert Barrow, photographer and co-author of the biography, Billy: The Life and Photographs of William S.A. Beal, says in a phone call from Swan River, about 500 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg. “Almost everything of purpose he did was for his community.”

Beal was among the first documented Black settlers in the province — and the first to settle the Swan River Valley.

As an avid reader and amateur photographer, Beal documented life in his Manitoba town at the turn of the 20th century.

With photographs and a handwritten memoir, Beal captured an intimate portrait of life on the rapidly changing Prairies, documenting the early influences of industry, immigration and western expansion.

Canadian immigration policy welcomes, and then bans, Black immigrants

William S. A. Beal, son of a bookseller, was born in Chelsea, Mass., in 1874 and educated in Minneapolis.

But not much is known about his life until he arrived in Manitoba.

At the turn of the 20th century, Canada launched an aggressive campaign to draw American and European farmers (deemed “desirable” immigrants) to the Canadian West. Farmers were offered a promising deal: the government would grant 160-acre homesteads for a nominal $10 fee, so long as farmers cleared and cultivated 15 acres within three years.

As a result, the Prairie population grew by over a million people between 1896 and 1905.

The Swan River Valley had been home to Cree and Anishnaabe for generations, and already had a storied history as a contentious fur trading hub when the immigration policy brought waves of Icelandic, American and European farmers to its dense woods.

Beal was by no means the only Black person to settle the Prairies — Black communities emerged in Amber Valley, Alta., and Eldon, Sask. — but he was the first to make a home in Swan River.

It would become clear Black immigrants didn’t fit the government’s “desirable” settler definition and it instituted several unofficial policies of deterrence before attempting to formally ban Black immigration to Canada in 1911.

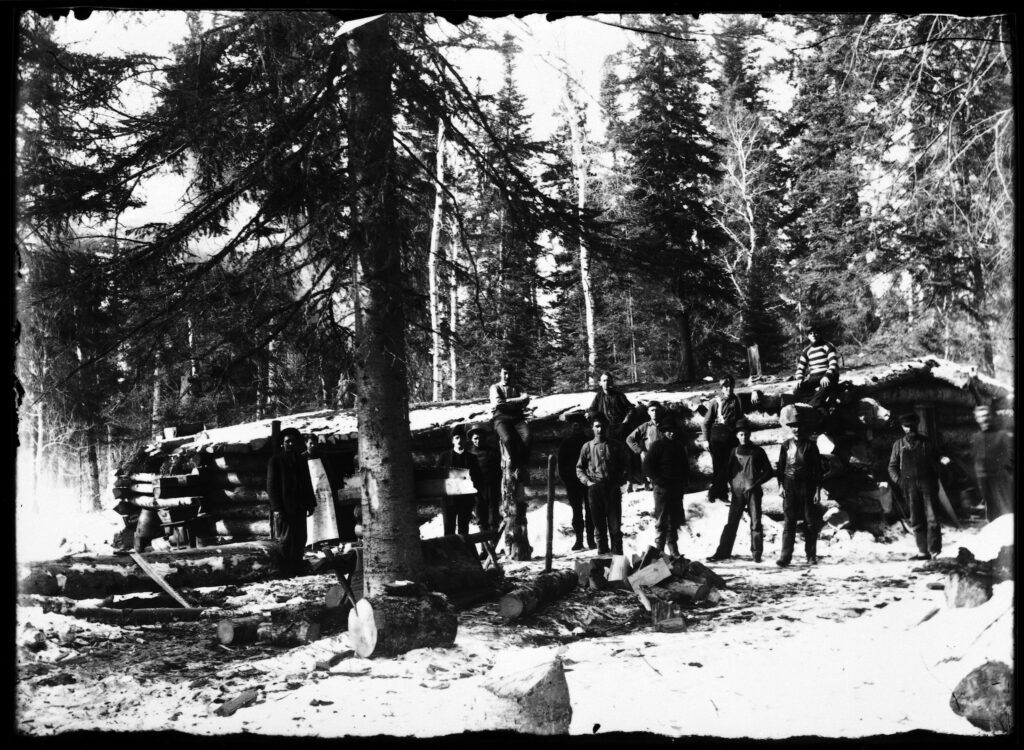

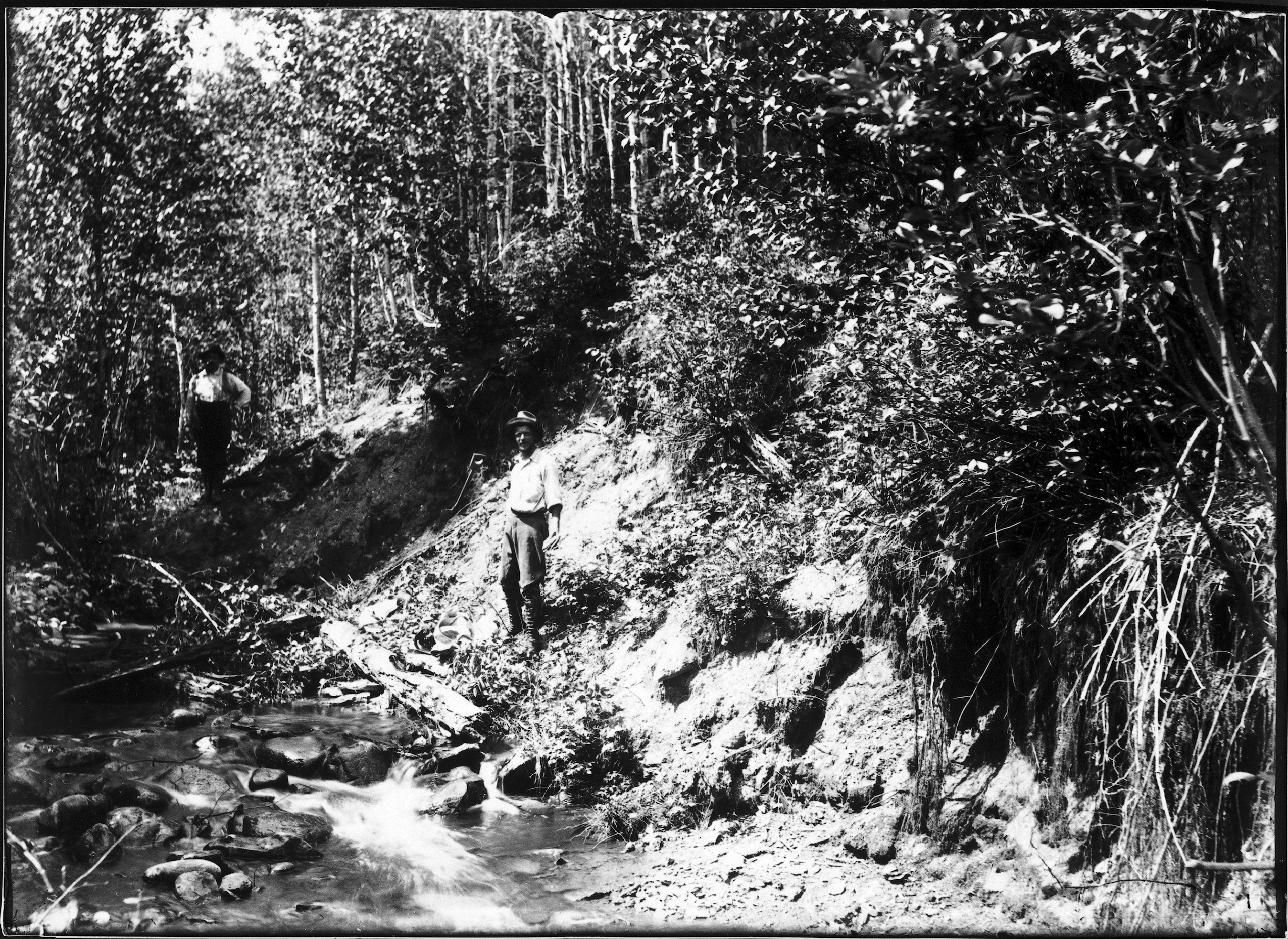

Documenting early clearing of old-growth forests in Manitoba

Beal built a career at the Minnesota sawmills — many of which provided lumber to Manitoba settlements. By the early 1900s, however, the northern states had nearly exhausted their supply of good spruce, and had begun turning to the Canadian forests for their harvests.

The Duck Mountain region was home to much of Manitoba’s old-growth forest. Though the old-growth trees have long been depleted, it remains one of few regions in the province where commercial logging still occurs.

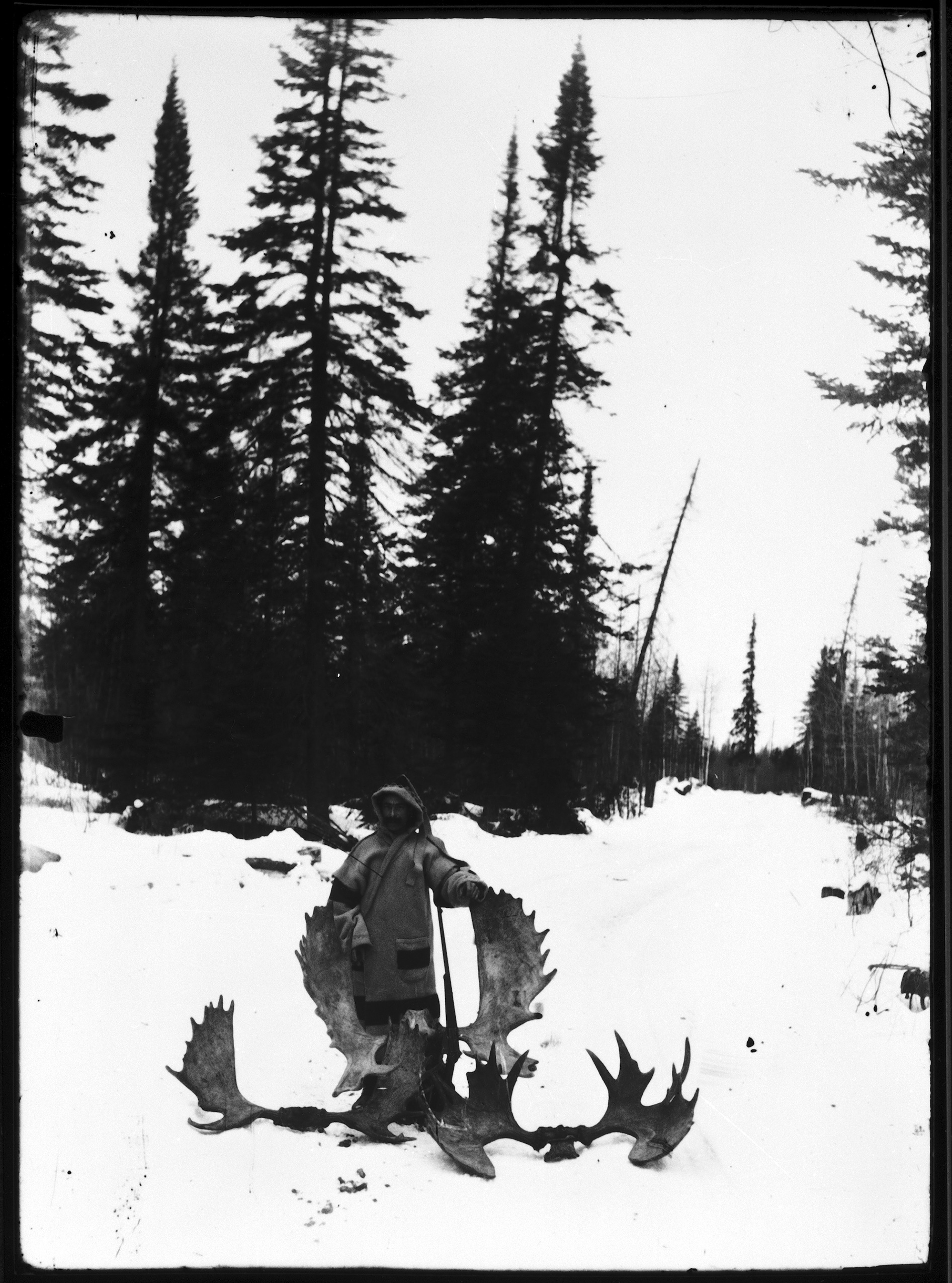

In those days, forestry was mostly a winter job. The bare trees and snow-packed ground meant fewer obstacles. In the spring, as the snow melted and the waterways began to run, lumber teams would drive logs into the river to float back to lakeside sawmills.

Trained as a steam engineer, Beal tended equipment that kept the sawmill running — an industry that continues to this day.

“Lumber and farming are still kind of the mainstays here,” Barrow says. “The old hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

Early homesteaders got cheap land in Manitoba’s Swan River Valley — if they could clear it

Over those long winters in the logging camps, Beal wrote, “there was nothing but homestead talk every evening.”

Eventually, that talk seemed to have an effect on Beal, in spite of his city-dwelling sensibilities. He applied for a homestead in fall 1908. Because he was late to cash in on the government promise, the only land available was a scrubby plot 16 kilometres north of the townsite on the banks of Big Woody River.

There were no roads out to Big Woody, or bridges across the river. Beal remembers cutting his own roads to build a “shack” to live in.

In those days, he wrote, no one grew grain or sprawling crop farms. Working the land to meet the 15-acre quota was a slow, grueling, “herculean task,” Beal wrote.

“My father put it this way: he said the government bet you $10 that you’d starve to death,” Barrow quips.

Indeed, Beal wrote not everyone could withstand the work. Most people grew small gardens and tended a few cattle. There was no guarantee crops would grow. The cold climate meant frosts would come even in the summer. Beal’s first garden grew nothing but potatoes.

‘The real treasure’ — Billy Beal’s dedication to Swan River

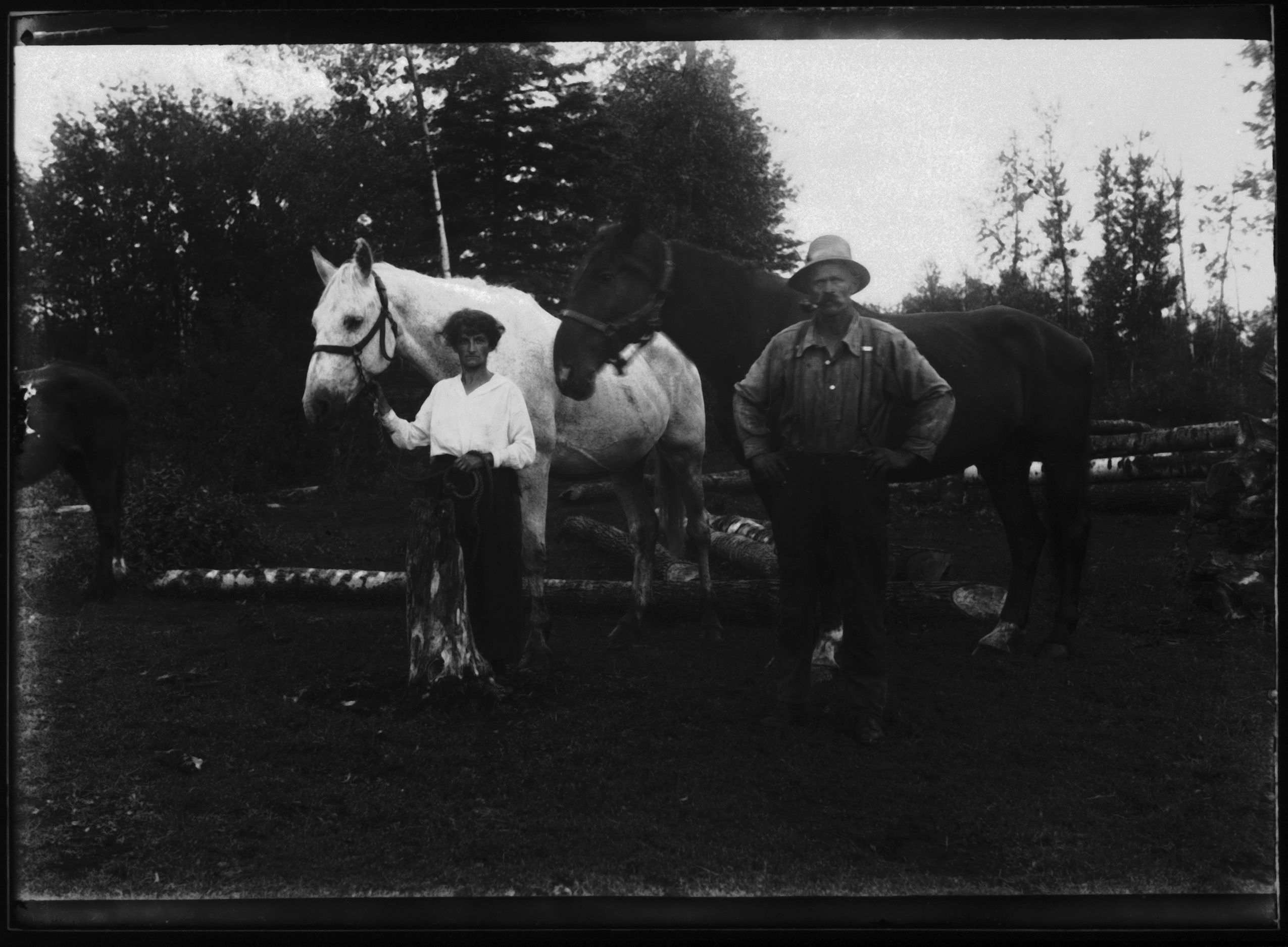

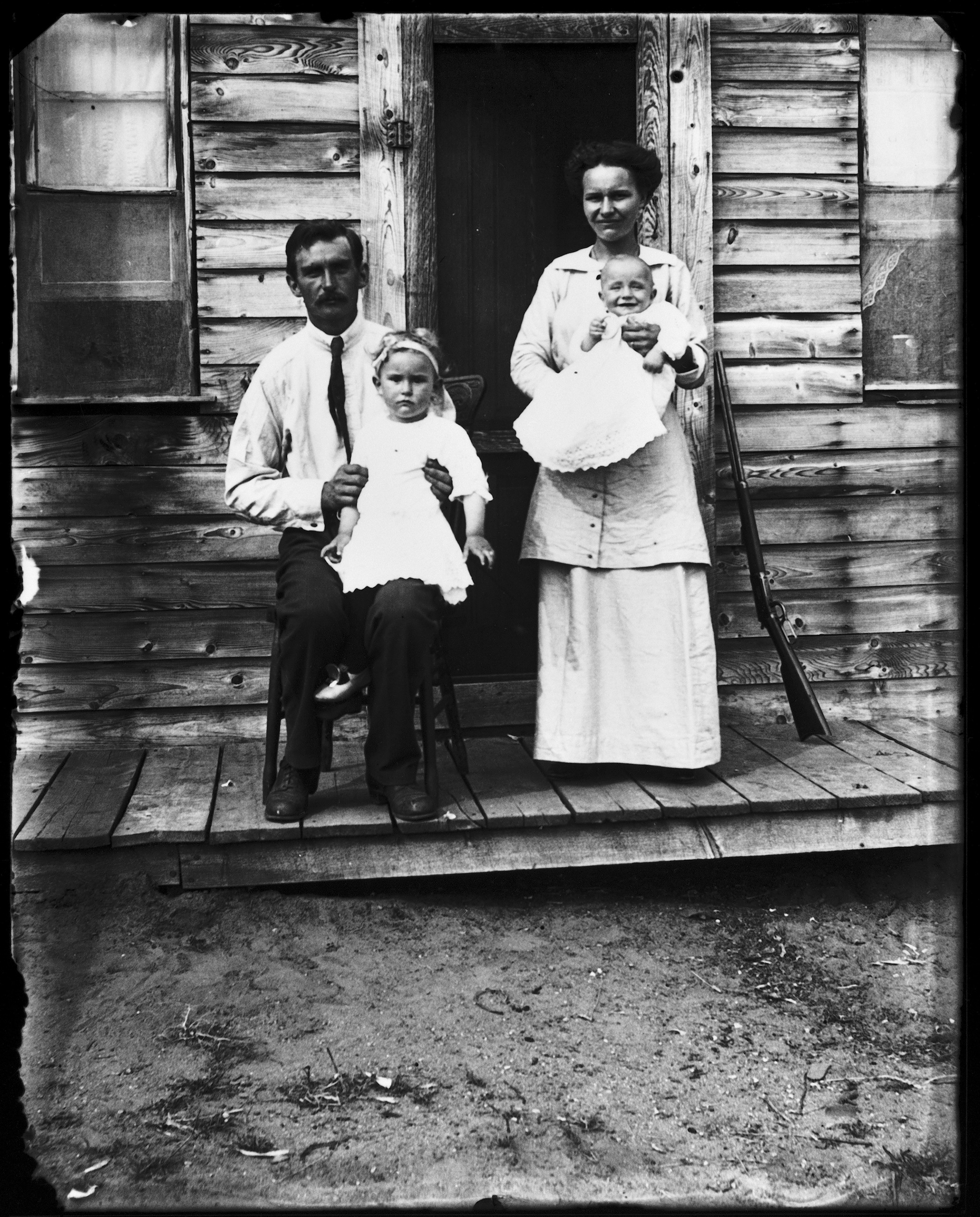

It was around this time, Barrow says, that Beal picked up a camera and some photography skills from another settler. The collection of about 70 plates that still exist were passed on to the Barrow family after Beal’s death in 1968.

There are scenes likely captured at house parties and local dances. There are portraits of neighbours surrounded by their livestock and crops. There are scenes of life on the logging roads, of tugboats pulling cookhouses up river to the work camps.

It’s the affinity for people in Beal’s work that’s always stood out to Barrow.

Through the intimate portraits — mostly of his neighbours — and the landscape images from his logging work, “you see the makeup of the community, and the kinds of occupations, trades and recreation that people were involved in,” he says.

According to Beal’s memoir, “everybody was friendly,” and eager to welcome him.

In return, he served the community in every way he could, Barrow says.

He built a telescope out of stovepipe and tin cans and taught his neighbours about astronomy. He built the town’s first radio and hosted the local children — including Barrow’s uncle — to listen to its signal.

When diphtheria threatened the town in 1915, and the influenza pandemic arrived a few years later, he helped the town doctor with vaccinations.

Barrow says Beal was instrumental in setting up a local debate society that gathered for all manner of philosophical and political discourse at the community hall. Unlike in most other homesteading communities, the Big Woody district school (another one of Beal’s contributions) is still used as a town hall today.

“The farms have gotten bigger, there’s fewer people and I suppose eventually it won’t be a viable option anymore, but to this point the community has stayed together,” Barrow says.

He attributes that connectivity, in no small part, to that of the community in Beal’s day.

“It’s one thing to build yourself up but it’s quite another thing to build other people up. That’s the real treasure,” Barrow says.

To this day, the Swan River Valley treasures Billy Beal. When Beal died a penniless, lifelong bachelor in 1968, the community built a headstone to honour him. They inscribed his story on a plaque outside the library and named the local ice-fishing derby in his honour.

“He was a wonderful man,” Don Brown, a Swan Valley resident who remembers meeting Beal as a young and shy child, says over a phone call. “Weren’t we lucky to have him come to this area.”

Beal, too, took pride in Swan River.

“Someone said back in 1906 … ‘We are just clearing this country for the second generation,’ ” he wrote at the closing of his memoir.

“The second generation is here and some are doing well. Very few of the original settlers are left. We have seen the district pass from the days of ‘oxen,’ to horses, to tractors and now combines. What will be next?”