In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Manitoba’s protected areas network has grown by just 400 square kilometres in the last seven years, according to analysis by The Narwhal and Winnipeg Free Press.

That represents just 0.06 per cent of the province’s land area at a time when global organizations are urging governments to ramp up conservation efforts and commit to protecting 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030.

To get there, Manitoba would need to nearly triple its existing protected area network, from just over 70,000 square kilometres to more than 194,000 square kilometres — but Manitoba’s leaders have refused to commit to 30-by-30 goals.

With the Oct. 3 Manitoba election fast approaching, environmental non-profit groups are calling on the parties to commit to reversing course by integrating a climate lens into all provincial policy decisions and committing to international conservation targets.

While the Environment Department (formerly conservation) has suffered cuts across the board, the protected area program has virtually disappeared from government budgets, stalling Manitoba’s progress toward international climate and biodiversity goals.

“If we’re going to solve the climate crisis, if we’re going to solve the issue of mass wildlife and species decline all over the world, we need to protect habitat, which means we need to protect nature,” Ron Thiessen, executive director of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society’s Manitoba chapter, said in an interview.

According to the United Nations, biodiversity is declining faster than ever. One fifth of the world’s land area has been degraded and nearly one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction, the most in human history. Biodiversity and habitat loss make ecosystems more vulnerable to climate change while having negative effects on human health and economic systems.

Manitoba has historically hesitated to sign on to conservation targets. The last time the province agreed to specific goals was in the 1990s, when the protected areas initiative program was first developed. Manitoba is ranked seventh — or dead-centre — among provinces and territories for the proportion of land and water it has protected within its borders.

The branch responsible for moving the needle on protected areas has been “chronically underfunded,” Thiessen said.

But financial investments and a dedicated team of staff for the program through the 2000s saw the network grow from 3,500 square kilometres in 1990 to almost 52,000 square kilometres — more than eight per cent of the province’s land area — by 2009, when Greg Selinger replaced Gary Doer as Manitoba’s NDP premier. The following eight-year Selinger term saw the network grow another 20,000 square kilometres to 11 per cent of the province.

Growth has flat-lined since.

More than half of the land added to the network in the last seven years came through the recognition of Canadian Forces Base Shilo, near Brandon, which is managed by the Department of National Defence. Another third of the land came as a result of updated reporting criteria for protected areas, which allowed Manitoba to classify an additional 130 square kilometres of heritage land owned by external groups like the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation.

The most recent addition to the network, Pemmican Island Provincial Park, had been designated an interim protected area years prior, but the Conservative government had allowed that designation to lapse in 2018 to open the area to mineral exploration.

Today, Manitoba makes scant mention of the protected areas initiative. There is just one passing reference to the program in the latest department report, stating the province “continues to contribute” to the network. The department has since been moved to the Department of Natural Resources and Northern Development. According to a statement from an unnamed government spokesperson, there is just one staff member working on the initiative today.

Publicly, the Progressive Conservatives have denounced global 30 by 30 targets. Responding to a Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society election survey distributed to Manitoba political parties, the Tories were the only party that refused to commit to conservation and biodiversity goals, instead calling the target “arbitrary” and claiming pursuing such goals “could harm economic development, particularly in northern communities and disrupt various sectors across the province that rely on land use.”

“It’s shameful,” Thiessen says. “The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, experts all over the world, have all agreed this is a necessary target, so to call that number arbitrary is misleading at best.”

Manitobans agree conservation should be a government priority.

A Probe Research poll conducted in June found 83 per cent of Manitobans want the province to move toward the 30 by 30 conservation target, while 60 per cent said they would be more likely to vote for a party that pledges to do just that.

“These are huge existential priorities,” Mark Hudson, a sociology professor at the University of Manitoba who has studied the links between labour issues and climate change, said in an interview. “If the government is not paying attention to climate and biodiversity, it’s got its head in the sand.”

Despite the government’s claims conservation could economically harm the north, four northern First Nations have been waiting months for the government to sign off on a project proposal that would add 50,000 square kilometres to the protected areas network while bringing economic and social benefits to their communities.

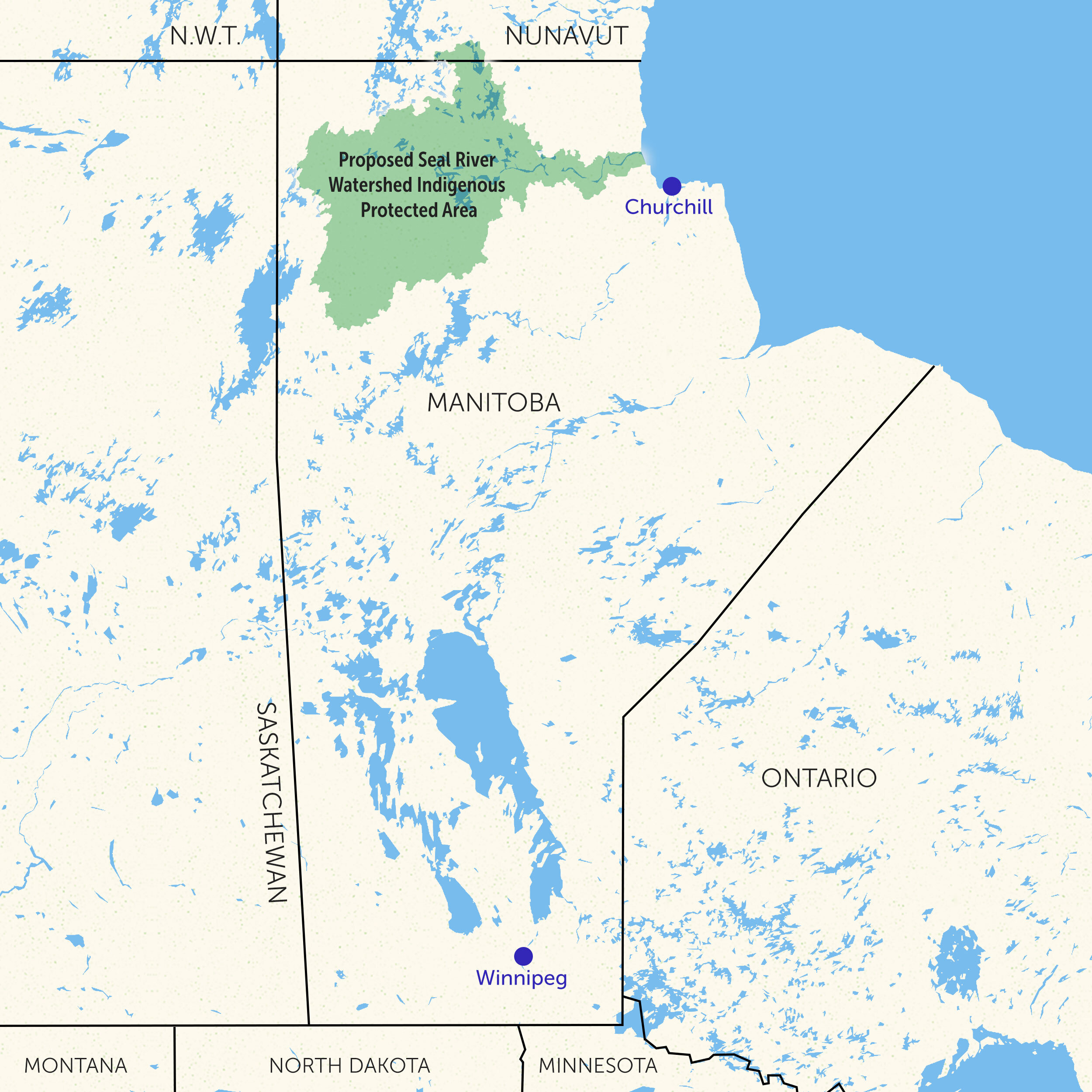

The Seal River Watershed Alliance, a coalition of four First Nations looking to protect Manitoba’s last undammed river and a pristine northern watershed, has gained local and international momentum since their proposed Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) was first announced in 2019.

Executive director Stephanie Thorassie has spoken about the project at conferences across the world, the alliance has secured federal funds and is in its second year of Indigenous Guardian training, which allows community members to learn traditional and western skills to lead tourism programs, conduct environmental monitoring and steward the land.

Progress toward an official protected area designation is well underway. The only hurdle they have yet to overcome is the provincial government.

“It’s been really frustrating because there’s so much positivity, there’s so much momentum and it’s a huge opportunity for the government to advance its commitments to reconciliation,” Thorassie said.

The alliance has been waiting nine months for Manitoba to sign a memorandum of understanding to temporarily ban mining and mineral exploration from the lands in the proposed protected area and allow the nations to complete a feasibility study for the proposal.

Thorassie said she’s been given the runaround as the ever-revolving door inside the Climate and Natural Resources departments lead to delays.

“It’s a constant merry-go-round,” Thorassie said. “Nobody ever does their homework, we’re just circling around, talking about the same thing over and over again, or there’s another cabinet shuffle and then we’re waiting for people to get up to speed.”

When asked to explain why the memorandum of understanding has not yet been signed, an unnamed spokesperson for the Manitoba government did not provide a specific answer, instead stating the project is “complex” and the province continues to meet with Parks Canada and the alliance.

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas like the Seal River watershed are increasingly recognized as the best practice for protecting lands and waters, understanding Indigenous Peoples are best equipped with the knowledge to steward their lands.

“Historically, we didn’t manage the land, we lived in harmony with the land,” Thorassie explained.

“All of this is about having respect for your siblings, your family — which includes the land — to be able to live together. It’s not about thinking that you’re better than the land and needing to manage above it and control it.”

There are currently seven other Indigenous protected areas in the early planning stages across Manitoba that would add a combined 10 per cent to the province’s protected areas network. But a lack of provincial investment and pressure from the mineral industry — which has likened protected areas to “sterilizing” the land — stands to delay progress.

“Meanwhile it’s the exact opposite,” Thorassie said. Mineral activity in nearby Dene territory has decimated vital northern ecosystems and caribou habitat, destroying large carbon sinks along the way, she added.

“How hard is it to convince the world that they need to breathe?”

Between the Seal River watershed, seven other IPCA proposals and a nearly 74,000-square-kilometre network of proposed protected areas mapped out by provincial staff in the mid-aughts, Manitoba could protect 40 per cent of its lands by 2030, according to Thiessen.

That still falls short of the proportion of land Canadians feel their governments should be protecting. A national Nanos Research poll conducted in October 2022 found Canadians, on average, want to see nearly half of the country’s land area (and more than half of its water) conserved — and the majority are willing to see the government spend more to get there.

More than 80 per cent of Canadians — and 86 per cent of Manitobans — indicated they would support increased government spending to expand the network of protected areas.

Respondents ranked government funding as the most important mechanism to support designating and managing new conservation areas, followed by fees for companies doing business on protected lands and fees to access protected areas.

“A lot of policy-makers are used to the status quo and used to the old way of doing things. I think it's really important for people to realize that it's not going to work anymore,” Thorassie said.

“This is an amazing opportunity to listen to what the people are saying and wanting, and it reinforces the teachings and the wisdom of our community members and our Elders.”

But the most significant barrier to protecting more lands, increasing environmental monitoring activities or implementing any number of key environmental services in Manitoba remains a dire lack of resources.

“There has been no time in Manitoba history that parks and protected areas, or the environment, have been funded sufficiently,” Thiessen said. “There isn’t enough staff to do the job required and the staff don’t have the budgets to do what they need to do.”

Updated Sept. 28, 2023, at 5:15 p.m. CT: This article and headline have been updated to clarify that the addition of 400 square kilometres to the province's protected area network represents 0.06 per cent of the province's land area, not a 0.06 per cent increase in the total protected area. The total protected area increased by 0.59 per cent.

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a reporter covering environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a partnership between The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...