Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Manitoba’s herd of iconic boreal woodland caribou are one step closer to having their population — and habitat — protected. This week, the federal and provincial governments signed an agreement re-affirming their commitment to protecting and recovering the threatened and declining population.

“Our boreal caribou populations have been in decline across the country. It’s an iconic species, it’s on our 25-cent coin, it’s a symbol of the Canadian wilderness and according to estimates there are between 1,500 and 3,500 left in Manitoba,” Terry Duguid, Winnipeg member of parliament and parliamentary secretary to the minister of environment and climate change, said in an interview.

“Obviously here’s a need for action to ensure this species has a future in our province and our country.”

Woodland caribou — cousins of the European reindeer — make their home in the boreal forests of nine provinces and territories, from Yukon to Newfoundland, but the animal’s habitat is continually lost to development. Caribou are known to avoid human activity, and require large swaths of undisturbed forest to find food and avoid predation. Because of their sensitivity to the landscape, boreal caribou can serve as an indicator of forest health.

The boreal caribou have been listed as threatened under the federal Species At Risk Act since 2003, while the province designated the local population as threatened in 2006. Both governments acknowledged the degradation, fragmentation and loss of caribou habitat owing to industrial activities, road development, wildfires and other human land uses have been the greatest threat to caribou populations. Shrinking habitat has left the species increasingly vulnerable to predators.

“This species is particularly sensitive to industrial activity and disturbance,” Duguid said. “Habitat really is the key to ensuring boreal caribou have a future in our province.”

The three-year agreement inked Wednesday culminates several years of advocacy and groundwork from conservation groups and government alike. According to conservation advocates, a formal plan for caribou protection in Manitoba is long overdue.

“As action plans for recovering high-risk caribou populations were initially due for completion in 2009, it’s great to see new energy and investment in protecting this threatened wilderness icon,” Ron Thiessen, executive director of the Manitoba chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, said in an emailed statement.

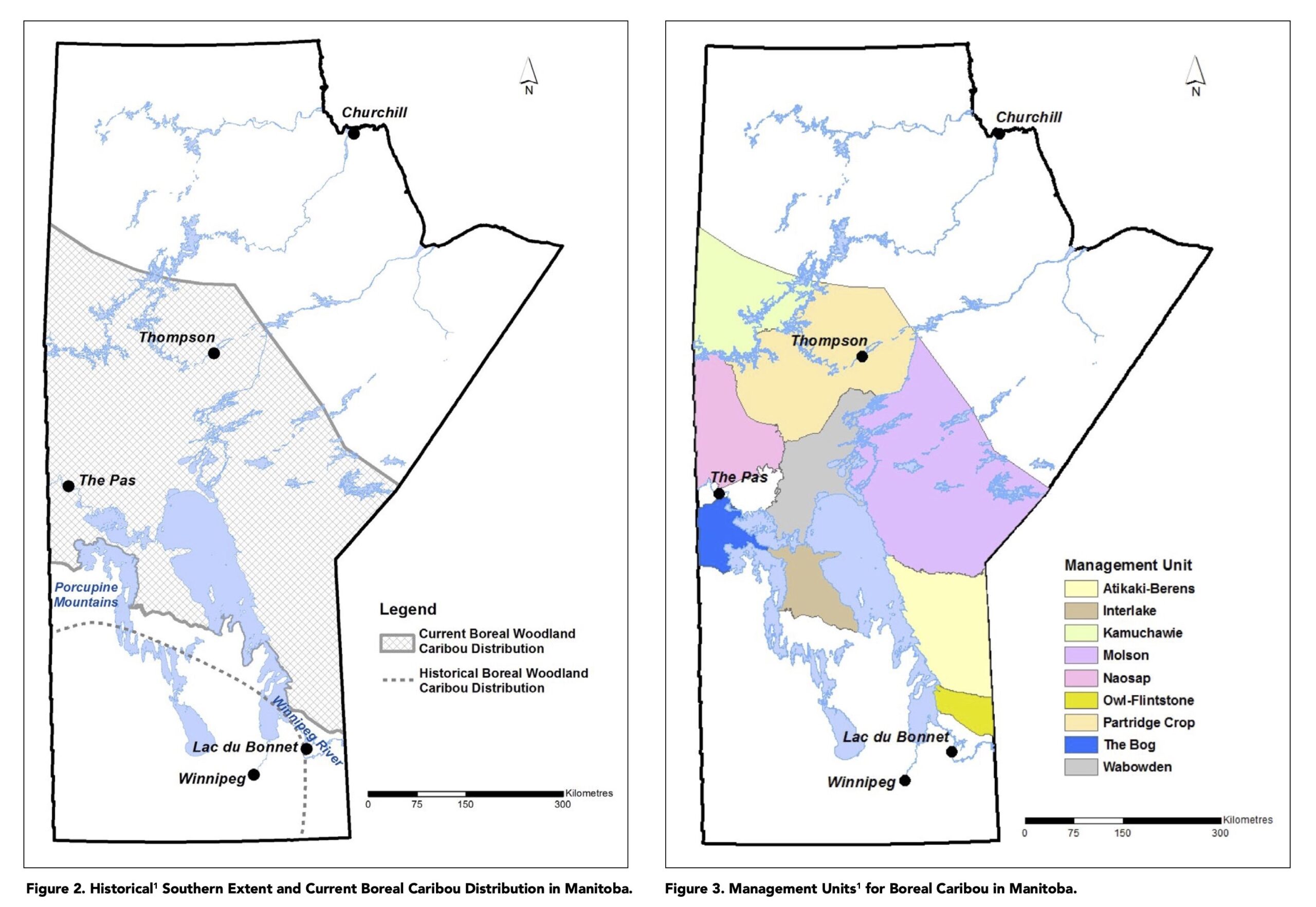

Manitoba has been working towards effective caribou management for decades, starting with a recovery strategy first released in 2006 and updated in 2015. The latter strategy delineated 15 caribou ranges within nine management zones and set a target to develop action plans for those management zones by 2020. The goals set out in the strategy were among the most ambitious in the country, Thiessen said, outlining a commitment to maintain between 65 and 80 per cent of intact caribou habitat within the management zones.

But those action plans never came. In the meantime, according to Natural Resources and Northern Development Minister Greg Nesbitt, the Manitoba government has been collaring, tracking and monitoring the caribou herd.

“We’ve certainly been monitoring our caribou and trying to get a handle on the population,” Nesbitt said in an interview. “They’re very mobile, they move around, they’re hard to survey.”

The new bilateral agreement, Duguid said, is meant to hold governments accountable to caribou conservation. Habitat protection, herd monitoring, data collection and other on-the-ground tasks will be carried out by provincial conservation officials, while the federal government plans to support those efforts through funding and knowledge sharing.

The federal government has already committed $1 million to support Manitoba’s habitat and herd management efforts, and has committed to further supporting Manitoba’s efforts in future years.

Nesbitt said the federal contribution will help support initiatives around habitat planning and protection, herd monitoring and predator monitoring, among other measures.

According to Thiessen, government efforts will need to go beyond habitat and population monitoring to recover and maintain caribou populations. At present, the new agreement amounts to little more than a pledge of federal help in developing Manitoba’s long-overdue protection plans, Thiessen said, adding he hopes to see formal and aggressive action plans in place by 2025.

“Protection of large, intact landscapes is required as it’s the only measure proven to sustain woodland caribou populations,” he said.

“Time will tell if the plans lead to large protected areas where industrial activities and associated road networks do not occur.”

Nesbitt acknowledged the province has been promoting mineral exploration in the north in recent years, though he believes such exploration has minimal environmental impact and noted industrial developments need to consider wildlife and habitat impacts before permits can be issued.

Still, formally designated conservation areas would allow governments to better regulate industrial activity on the land, while helping Canada move toward the biodiversity and conservation targets set at December’s COP15 biodiversity conference in Montreal, where Canada reaffirmed its commitment to protecting 25 per cent of its lands and waters by 2025, and 30 per cent by 2030.

“We need industrial activity, we need to protect our wildlife and ecosystems,” Duguid said. “We are a big country — we can do both.”

Both federal and provincial governments plan to develop management plans alongside Indigenous communities who “live among the caribou and have a spiritual connection that goes back in time thousands of years,” Duguid said.

“We will not only be relying on traditional science, but also on the Traditional Knowledge of these communities — and that’s going to help us particularly in the management of rangelands where caribou are found,” Duguid added.

A provincial consultation department has been engaging Indigenous communities on wildlife management for many years, Nesbitt confirmed.

Across Canada, governments are increasingly looking to First Nations for Traditional Knowledge and input on caribou protection. “Since time immemorial, First Nations have searched out caribou for sustenance and nutrition,” read a joint report by the Assembly of First Nations and David Suzuki Foundation. “Across Canada today, boreal woodland caribou herds share the land with approximately 300 First Nation communities.”

“They are the experts on their traditional territory and we respect that and we want to work with them,” Deguid said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion