Our trial is a week away

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

Over the past four years, the Manitoba government has been seeking a resurgence in its century-old mining industry.

While progress has been slow — owing in part to financial downturns in the pandemic — there are signs mining in Manitoba is on the cusp of something of a boom.

“The world has discovered that the combination of Manitoba’s critical mineral and strategic resources, our affordable, reliable, renewable energy and our highly skilled workforce will be key to creating the materials and products that will drive the world’s energy transition,” Premier Heather Stefanson said during November’s throne speech. “This is best illustrated by the record investment by global companies in mineral exploration in Manitoba last year.”

With green technologies, including electric vehicles, prompting a boom in critical mineral production, Manitoba is positioning itself as a global leader in mineral resources, even as some conservation advocates ring alarm bells about the industry’s potential impacts on the landscape.

Manitoba’s sustainable development policies for mining lack clarity and consistency, according to Heather Fast at the Manitoba Eco-Network. While there has been “lots of discourse on economic and political benefits” of mining, she said, there hasn’t been much discussion of “the environmental piece.”

At the same time, many northern First Nations are looking to take a leadership role in the mining industry, moving beyond consultation to partnerships that balance environmental protection and local economic sustainability.

“It’s a new era,” Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Grand Chief Garrison Settee said in an interview. “First Nations are coming into a position where they can be partners in anything that happens when it comes to resource extraction.”

Large quantities of lithium, nickel and silica sand, as well as historic deposits of gold, silver, copper and diamonds have brought new players into Manitoba’s mining sector, as headlines around the world predict a green mining boom. What does the potential influx of new mining in Manitoba mean for the future of the province?

Mining has always been part of Manitoba’s economy. Salt and limestone mining began in the early 1800s; brick quarries were among the province’s first industrial sites. Gold was discovered near Falcon Lake later that century and the first gold shipments began in the early 20th century. Over the decades, mineral discoveries led to mining regions — and emerging towns — near Flin Flon, Bissett and Lac Du Bonnet as the industry grew to include base metals like nickel, copper and zinc.

After centuries of practice, in 2016, the Fraser Institute — a right-wing, pro-industry Canadian not-for-profit research group — released an annual survey of mining companies that ranked Manitoba the No. 2 destination in the world for mining investments. It was the fifth straight year of growth in the province’s attractiveness score — owing largely to new regulatory clarity, according to the survey.

But in the years that followed, Manitoba’s reputation tanked. By 2020, the province had fallen to 37th.

Despite the falling reputation in industry circles, which mining executives linked to uncertainty over disrupted Indigenous land claims and protected areas along with lengthy permitting delays, actual spending in the sector was slowly rising.

Between 2015 and 2021, mining companies spent an average $60 million annually on mineral exploration and mine appraisals in Manitoba. Last year, according to Natural Resources Canada, those expenditures were predicted to hit almost $170 million — nearly triple the average of the past seven years.

That’s due in large part to what are known as critical minerals. In 2021, the Canadian government released a list of 31 critical minerals deemed key to the country’s economic development, national security and transition to a low-carbon future.

Minerals in this category saw record investments, according to a statement from the provincial government. Companies invested nearly $111 million in Manitoba’s stock of lithium, cesium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, potash, tantalum, uranium and other minerals the federal government have deemed key to a green future — a 240 per cent increase over 2018 spending.

The attractiveness of a mining jurisdiction hinges on two main factors — geological features and government policies. Manitoba’s landscape is rich in minerals, but companies frequently complain about provincial policies around consultation with First Nations, environmental protection and the permit process.

One anonymous company president told the Fraser Institute “the establishment of parks and protected areas without consultation of the industry hurts the province’s competitiveness,” while another claimed “rules around First Nations consultations are vague and uncertain.”

Neither the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada, the Manitoba Prospectors and Developers Association or the Mining Association of Manitoba responded to interview requests.

The province seemed to take these criticisms to heart; when Stefanson gave her first speech from the Throne in 2021, she said “northern communities and First Nations have abundant mineral resources on their doorsteps, yet mining activity is not what it could be,” and promised the province would work to improve its standing on the global mining stage.

Days later, the province announced a rule change allowing mining companies to hold permits for three years at a time, rather than renewing their permits every year.

The government is also hoping to encourage mineral exploration through tax incentives and dedicated funding.

The Manitoba Mineral Development Fund, a $20-million provincial fund doled out by the Manitoba Chamber of Commerce, had launched in 2020. After a slow first year laden by pandemic economic challenges, the fund built momentum in 2021, approving more than $2.2 million in funding for 17 projects. The bulk of that funding was handed over to mining companies to support exploration and other projects.

Now, the province is taking things a step further by developing a comprehensive mining strategy.

“Manitoba has not had a comprehensive mineral/mining strategy for over 20 years,” Jeff Wharton, Manitoba’s minister of economic development, investment and trade, said in an emailed statement.

“Manitoba’s strategy is aiming to grow mineral exploration and development in Manitoba, including specific focus on critical minerals, by encouraging investment, enhancing geoscience knowledge and sustainable land use management and increasing Indigenous participation in all phases of the mineral cycle.”

The long-term plan is expected to be ready in late spring, and will focus on reducing what the government and industry dub red tape, increasing Indigenous participation and ensuring the sector is environmentally sustainable, Wharton added. In particular, the province plans to focus on encouraging mining of critical minerals.

“Critical minerals are the building blocks for the green and digital economy,” the federal government has said of its list of 31 critical minerals. Metals like cobalt are used in hydrogen fuel cells, batteries and jet engines; nickel is a key component of electric-vehicle batteries, health-care technologies, solar panels and aerospace technology; graphite is used in electric car fuel cells, rechargeable batteries and brake systems.

According to Jamie Kneen, a national program lead with Canadian industry watchdog Mining Watch, the critical mineral list has led to “huge hype” in the mining industry across the board. That hype, he said, is “driven by the energy transition to support climate action,” with the critical mineral list creating a “promotional machine run amok” for the mining industry.

“It’s great [for industry] because it’s bulletproof,” Kneen said. “You can’t criticize it because it’s for the good of the climate.”

Of the 31 critical minerals, few have received as much global attention in recent years as lithium. The highly reactive metal is among Canada’s top-six priorities for mineral development under its critical mineral strategy. Because it is a key component of rechargeable batteries — used in laptops, cellphones, electric cars and even power grids — lithium demand (and pricing) has spiked, dropped and spiked again since 2017.

That boom and bust in demand projections have helped spur the frenzy of new exploration investments, Kneen explains. But Canada has produced very little lithium to date; the only active lithium mine in the country — the Tanco Mine — is in Manitoba.

Demand for critical minerals like lithium are set to skyrocket as countries across the globe progress toward carbon-reduction goals — specifically when it comes to transportation. Canada, for example, aims to make all new vehicles zero-emission by 2035, increasing the demand for minerals like lithium, nickel and copper. Lithium demand could increase six-fold compared to 2021 production by 2030, according to projections from the International Energy Agency. Nickel and cobalt are expected to see rising demand, too.

But those demands could change as new vehicle and battery technologies evolve, Kneen said. Cobalt already took a sharp downturn in projected demand, and experts aren’t sure if lithium will follow suit in the coming years.

Still, the mining industry operates with a “gold-rush mentality,” Kneen said. Companies will spend heavily in the exploration phase, hoping to secure a windfall, despite knowing a small handful of projects will succeed.

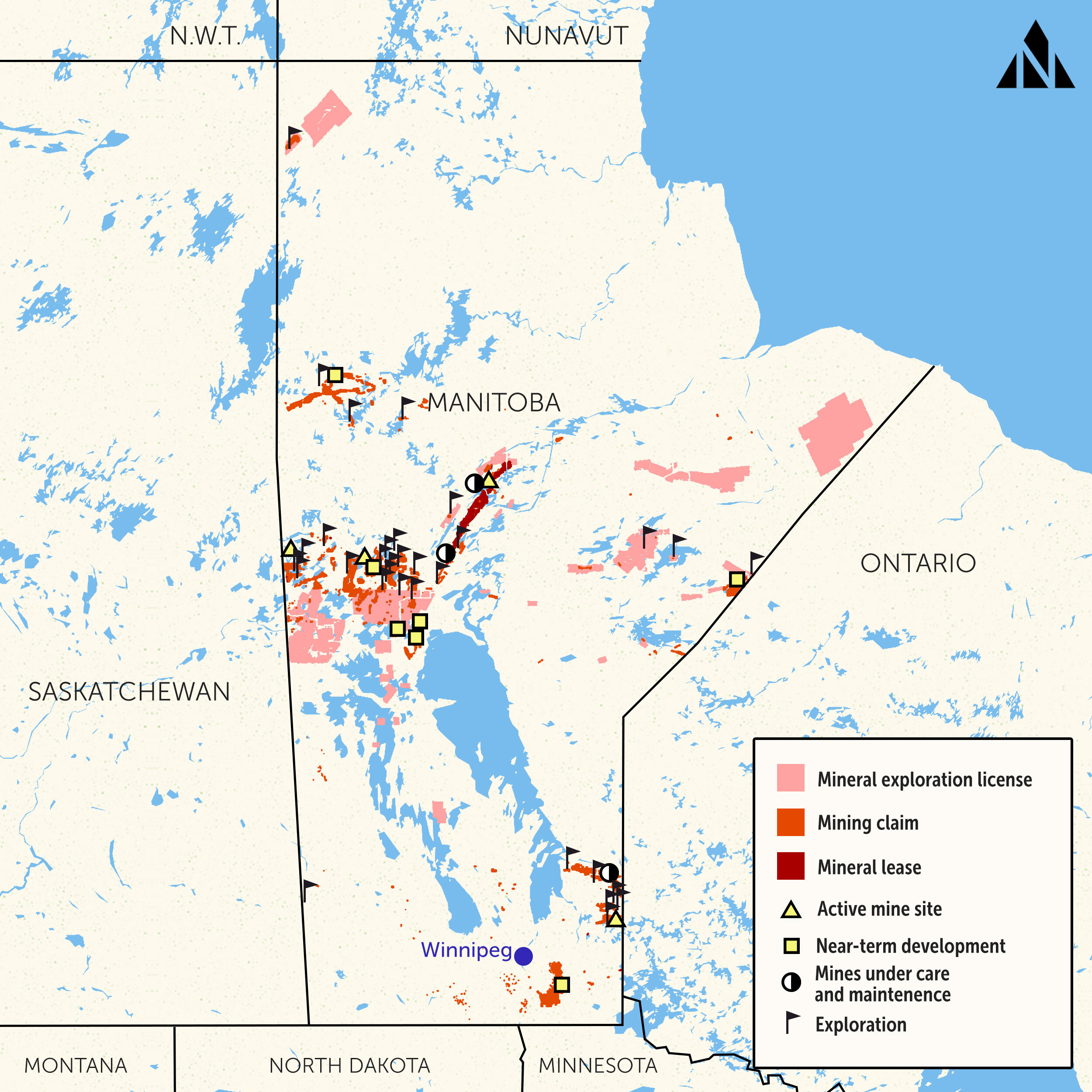

Manitoba boasts large lithium deposits from as far south as Cat Lake, to Cross Lake, in the north, a rich nickel belt near Thompson and significant amounts of copper, cobalt, zinc and other critical metals — and these metals appear to be driving the province’s renewed mineral investments. There are seven lithium mines in various stages of development in Manitoba, four nickel and copper mines, nine copper, zinc and precious metals mines, and a handful of exploration projects for elements like graphite, silica sand, potash and uranium.

But even as governments pitch critical mineral mining as essential to a less oil-and-gas-fueled economy, Fast warns it could “follow the same path” as oil and gas extraction if broader over-consumption issues are not addressed.

During last November’s throne speech, Stefanson claimed record international investment in the province’s mineral exploration industry. The province said 15 companies received new exploration permits in 2022, and while they wouldn’t list the companies, several have made headlines as they race to secure capital for their Manitoba-based ventures.

Manitoba’s lithium mining has seen significant growth in recent years. The Tanco Mine, near Bernic Lake in the Lac Du Bonnet mining district, had been running since 1969 but gave up on lithium several decades ago, when demand for the metal was low. In 2019, the mine was bought by the Chinese mining company Sinomine, and lithium production was back up and running last year. Sinomine now plans to ramp up lithium production by investing $176 million in a new concentrator that can handle six times the volume of ore.

New Age Metals, a Vancouver-based junior company that partners with more experienced mining companies, shares land in Manitoba’s lithium deposit with Australian mining giant Mineral Resources Limited. New Age has a partnership with Sagkeeng First Nation and plans to work with the Nation on exploration and development of the mine. The company has received several payouts from the Manitoba Mineral Development Fund for exploration technology and to help pay for a project training residents from Sagkeeng to be field workers on a New Age property.

Wolfden Resources, an Ontario-based mining company founded in 1995, holds two Manitoba properties: Rice Island and Nickel Island, and plans to produce nickel as a critical mineral. Both projects are still in early stages, and have been backed up by provincial funding. Wolfden has worked with the nearby Island Lakes Tribal Council — including a government-funded drilling demonstration for the council. Outside of Canada, the company’s CEO has come under fire for stating there are “no Indigenous Rights in the state of Maine,” where the company has invested in a mining project, and that the lack of rights “streamlines the permitting process.” The company has also been embroiled in a regulatory battle over its plans for environmental protection at the mine.

Snow Lake Lithium — owned by Australia-based NOVA minerals — promises to open a fully electric lithium mine in northern Manitoba. The company has a partnership deal with battery manufacturer LG Energy Solutions to develop and supply a lithium hydroxide processing plant in southern Manitoba.

Companies like Foremost Lithium, ACME minerals and Hudbay have also snatched up lithium exploration rights near Snow Lake and Bissett, hoping to capitalize on the need for critical minerals to fuel electrification.

In early exploration phases, it’s hard to tell how much impact new mining investments will have on the land. Exploration can take various forms over several years, ranging from flying helicopters fitted with magnetic sensors over the landscape to exploratory drilling to extract core samples from the rock.

While these activities can disturb local wildlife, more concerning is the fact exploration activities are “not terribly well-regulated,” Kneen said. There are rules to prevent fuel spills and cap drilling holes, for example, but “there’s no monitoring, there’s no inspection,” and any impact to land, water and wildlife tends to “fly under the radar.”

In Manitoba, prospective mining companies have been careful to propose more environmentally conscious approaches to their work. Snow Lake Lithium, for example, plans to use all electric equipment to create a zero-emission mining project, while other lithium miners have emphasized the “hard rock” extraction approach proposed in Manitoba — which extracts lithium compounds from a crystal called spodumene found in mineral formations known as pegmatites — poses less risk to watersheds than the “brining” approach — where lithium-rich water is pumped to the surface and dried in a series of ponds — used in other jurisdictions.

Regardless, Kneen said, “the cumulative effects can be massive, especially on wildlife.”

Those cumulative impacts — which look to consider past, present and future impacts of several projects in a particular region — are a concern for Manitoba Eco-Network’s Fast.

Noticing an “explosion of interest both federally and provincially”, the eco-network has been ramping up engagement with communities impacted by mining operations and helping contribute to provincial and federal environmental impact assessment processes. Fast said she’s noticed a lack of data collection, monitoring and transparency under Manitoba’s mining regulations, meaning there’s no baseline to determine the impacts of new mines on the local environment.

“Seeing the potential for lots of new developments in areas where mining resources are grouped together, something that we think is very important would be more emphasis on regional cumulative effects assessments,” Fast said.

“Can the ecosystem in these areas really handle more mining operations?”

Communities in Manitoba’s north — predominantly First Nations — have long had a relationship with the mining industry.

For many northern communities, mining is a source of employment, revenue and infrastructure. After November’s throne speech, mayors of Thompson and Snow Lake, both prominent mining towns, told the Thompson Citizen they were encouraged by the provincial government’s dedication to investing in the industry that sustains the north.

“Mining is what drives the town, it really is the lifeblood around here,” Snow Lake’s mayor, Ronald Scott, said, adding about 90 per cent of the town’s economy is created by mining.

Even while touting the province’s mining investments, Thompson Mayor Colleen Smook warned any new developments would need leadership from Manitoba First Nations.

As leader of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, Settee represents 26 northern First Nations — including many communities heavily impacted by resource extraction. In an interview, Settee said in days past, “resources have been extracted from our territories for a long time without having First Nations benefit from those resources.”

But Settee has noticed a shift brewing.

“Those days are over when corporations and mining companies come into our territory and start extracting resources without our involvement or a revenue sharing process,” Settee said. “We’ve been marginalized from the economy for the longest time, but those days are changing.”

The Manitoba-First Nations Mineral Development Protocol was established to help increase Indigenous participation in the mining industry. A 2019 action plan developed under the protocol proposed a streamlined approach to consultation with First Nations leadership, an Indigenous mineral education training program to help First Nations respond to mineral development proposals and guides for mining proponents looking to engage with Indigenous communities.

Already, several First Nations have entered partnerships with companies to share revenues, develop skills programs and create jobs as projects progress, according to the statement provided by the Manitoba government, which listed several examples. Alamos Gold, which owns a mine near Lynn Lake, has partnered with Marcel Colomb First Nation to train youth for jobs with the mine when it becomes operational later this decade. Manitoba’s first potash mine near Russell, developed by the Potash and Agri-Development Corporation of Manitoba, will share 20 per cent equity with Gambler First Nation. Sagkeeng First Nation has development agreements with Grid Metals and ACME Lithium as the companies explore lithium projects in the Lac du Bonnet region. Those agreements have helped facilitate ongoing engagement between the nations and mining companies, according to the government.

Manitoba’s government has touted these agreements as “key economic reconciliation efforts,” according to Wharton’s statement.

Economic reconciliation, for Settee, means ensuring First Nations “are part of the wealth and prosperity” of any mining operation. Northern First Nations, he said, are taking a careful approach to accepting new funding and partnership opportunities to ensure the benefits are sustainable.

“I believe that every decision we make impacts our people, and we want to make sure we do what is right, we do what is environmentally safe and not just jump at the opportunity when there’s funding being offered to us.”

Not all Manitoba mining projects have proceeded with approval from local First Nations. Flying Nickel Mining Corporation has been in consultations with Norway House Cree Nation since February 2021. The Nation has expressed concerns the mine would interfere with trapping practices or harm the environment in their resource management area near Grand Rapids.

While Settee acknowledges “there has to be resource extraction,” he emphasized the need to protect future generations by ensuring there’s minimal damage to the environment. Getting that balance right, he said, requires First Nations “sit at the table to make these decisions.”

Mining is slow business. Despite record investments, moving a mine from exploration to production can take decades. Experts suggest a boom — particularly in critical minerals — might not be realistic.

“There’s investment pouring in, but it’s going to land in a bucket of ice water pretty quickly because people are going to realize, for one thing, there are real constraints on what you can actually develop logistically,” Mining Watch’s Kneen said.

Because mining is historically a boom-and-bust industry, investors get cold feet when speculation starts to turn on their projects, Kneen added. Long delays finalizing permits, environmental licences and community consultations can also prompt investors to back out before a mine comes into being. Though there is “lots of hype” around critical mineral mining in Canada, and some of the proposed projects will likely become operational mines, it’s not yet clear what will succeed and what might fail.

The market for lithium, for example, has so far been dominated by international players, and Manitoba’s investments could be too little too late. Despite local excitement that a lithium boom could be on the province’s horizon, it’s still too early to know what returns those investments will generate.

“It’s all based on speculation,” Kneen said. “Speculation goes up and then it evaporates.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...