5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

It had been a tough game for the boys from Brandon. A crushing 15-6 defeat in their first playoff matchup of the day left the Heritage Co-op team with one more chance to avoid last place in the tournament. Not to mention the weather was an opponent all of its own, with air temperatures dropping to -30 C on the open expanse of Manitoba’s Minnedosa Lake, made even colder by the whipping winds.

Still, spirits are warm inside the heated, green canvas tent serving as the tournament’s makeshift locker room.

“It’s cold, the other team had a few more skilled players than we did today,” Brenden Chudley says, tongue in cheek, as his teammates slump onto a row of straw bales to unlace their skates and catch their breath.

“It’s fun, everybody’s here having a good time — and how often do you get to play pond hockey outside on the lake?”

Things are more jovial — though no less frigid — just a few feet away, where their opponents, the Integra Tires, crowd around one of a few tubes pumping warm air into the tent.

They’re excited about the win, but what’s really made the day special, player Nick Cameron says, is the people.

“Everybody gets back for one weekend and they all have fun,” he says.

Like the Co-op crew, most of the Integra team is from out-of-town, but they grew up playing organized hockey together in Minnedosa. They’ve come home for the February long weekend to take part in Manitoba’s largest pond hockey tournament: Skate the Lake.

Pond hockey is synonymous with Canadian winters: kids lacing up skates on a pond, lake, river or creek, to pass a puck around and shoot at a patchy net, or a gap between a pair of boots.

“For us to have this kind of ice in our veins and collective experience of outdoor sport and play in that context is unique and special,” sports ecologist Madeleine Orr says in an interview.

“Nothing quite transcends like hockey, and part of that is shinny. It’s not by yourself, it requires community — and that’s the magic.”

Shinny is said to be a precursor to ice hockey, evolving in Canada out of a combination of Indigenous and Scottish ball-and-stick sports. Even as hockey grew into an international phenomenon, the tradition of an informal pick-up game among friends on a patch of wild ice remained at the heart of the sport. Even hockey icons like Sidney Crosby have fond recollections of honing their skills on outdoor rinks.

“[For] small-town prairies … it’s a winter social activity,” Tanis Barrett, part of the original Skate the Lake organizing committee, says.

There’s no doubt outdoor ice rinks provide a sense of community and an opportunity for people of all ages and backgrounds to learn a new skill, though it’s not as ubiquitous as it used to be, her husband, Wes, notes. Fewer farms have resulted in smaller rural communities and fewer opportunities for a bit of impromptu shinny.

“For most of these kids, they’ve never had this opportunity to play outdoor hockey,” Wes Barrett says. “Giving kids these kinds of opportunities is maybe a little bit of a look back in time.”

It’s not just the decline in rural populations that threaten the future of pond hockey. While this year’s tournament, with nighttime temperatures well below -30 C, wasn’t threatened by what are known as “lost winter days,” climate change experts say unseasonably warm days are becoming more common. So too are more variable freeze-thaw cycles and less predictable snow cover — all of which could put an enduring image of Canadiana on thin ice.

Described as a homecoming, a town reunion and a big party by attendees, Skate the Lake has been a Minnedosa fixture since 2007, when a group of families came together to plan a unique fundraiser for the town’s minor hockey teams.

The Barretts remember their friends Dan and Gaylene Johnson mentioning Plaster Rock, New Brunswick’s annual shinny fest — dubbed the World Pond Hockey Championship — and asking: “Well, we have a lake, why don’t we use it?”

They recruited volunteers from the minor hockey community, gathered around the Johnson’s dining room table and set to work planning what would eventually grow into an annual tradition for the town of 2,700.

“We were lucky enough to be involved from the beginning and it’s been great to see,” Tanis Barrett says in a phone interview the week before the event.

“Getting to see my kids coming back as grown-ups is super satisfying.”

Under the glaring sun and unending, winter-blue sky, Minnedosa Lake has a magic quality about it. Clusters of colourful ice-fishing shacks flank the makeshift hockey rinks; quaint cottages line the far shoreline.

The lake is only about six metres deep, and at 94 hectares it’s “in that Goldilocks correct size,” Tanis Barrett says.

It’s human-made, created in the early 1910s as a reservoir for the small hydroelectric dam that would eventually make Minnedosa just the second Manitoba town to generate its own electricity.

After the dam was phased out of service in the 1930s, the lake grew into a destination for swimming, camping, boating and picnicking. It gained some international fame in 1999, playing host to the rowing, canoeing and kayaking events during the Pan American Games.

That legacy carries on in the canoe clubs, kayak clubs and dragon boat teams that use the lake through the summer months. Events like Skate the Lake give the town another way to appreciate the lake in the winter, too.

“It gives people a connection to the community and to the water,” Wes Barrett says. “It’s just a great way to celebrate the winter.”

Barrett says the last few years have come with more weather unpredictability. It’s gotten windier in the shallow topographic bowl where the lake sits; it’s gotten difficult to predict how much snow they’ll have to work with.

One year the tournament had to be postponed because a windstorm had sent the military-grade tent flying down the beach and mangled the metal poles. Another year was so warm the ice turned to slushy puddles, and the afternoon games had to be moved to the town’s indoor rink.

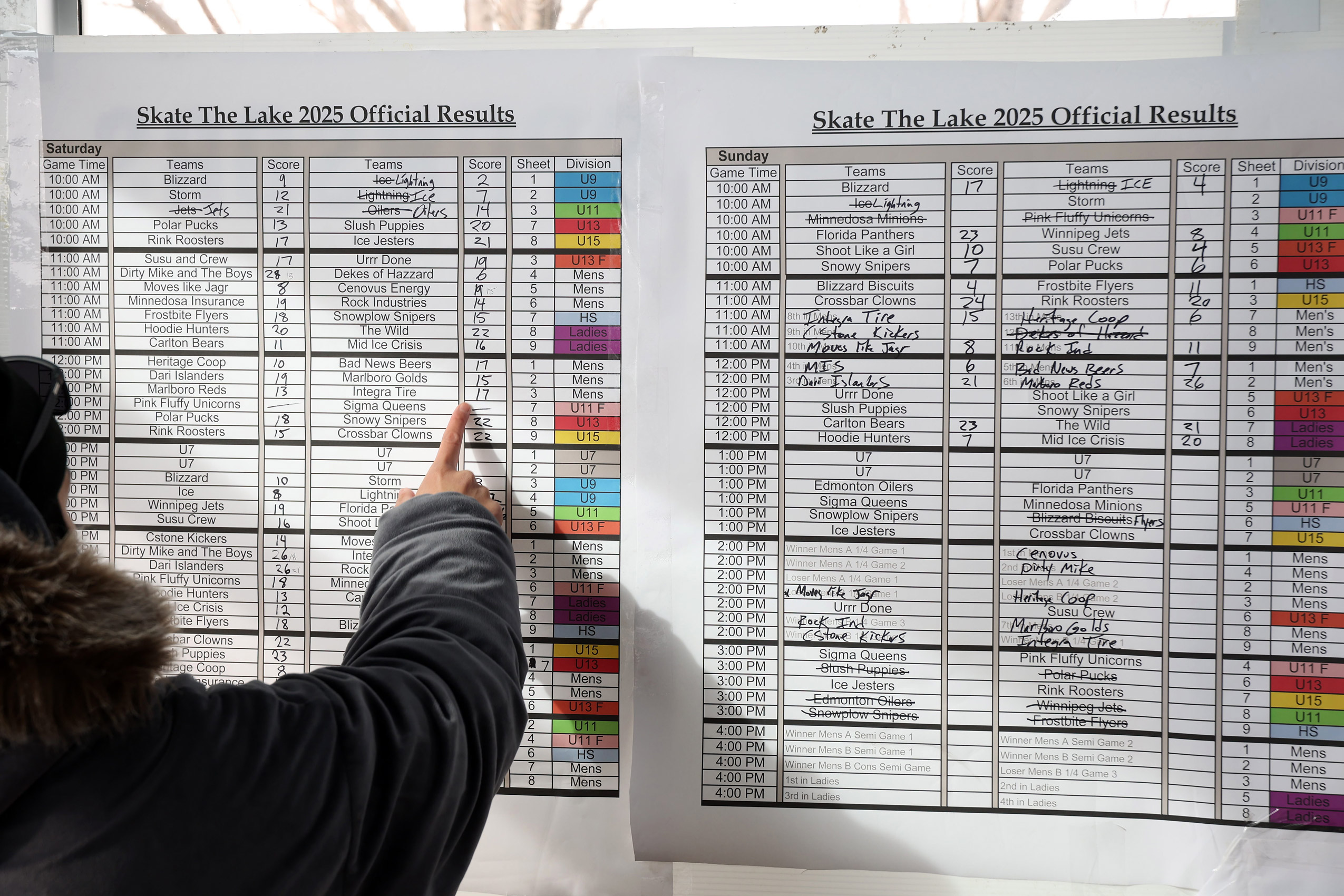

The tournament is contested on 10 snowbank-lined rinks, where four-player teams face off, without goalies, over 30-minute games, aiming to score on specially made nets just a few inches tall. There are separate round-robin draws for mens’, womens’ and youth teams. Everything is run by volunteers — mostly minor hockey families who commit a few hours of the weekend to work the bar, serve food, maintain the ice or keep score.

About six years ago, organizers added curling to the weekend festivities and the Rock the Lake championship has been just as hotly contested (mostly just for fun) ever since. As a bonus, organizers made room for what Barrett calls the “over-60 crowd” to compete in the rousing stick-curling “pondspiel.”

Arlene Almey and her husband Nelson — competing under the team name “Slide Show” — are second-time competitors, popping in from their home across the lake. Their daughter and son-in-law are playing this year, too. Arlene is 70, and despite the cold, she says, “it’s just as much fun” as the year before.

“I love when we have a grandma and grandpa playing curling, a mom and a dad playing hockey and then their kids,” Barrett says. “Three generations — that doesn’t happen very often with a sport.”

By mid-day, a misty fog has descended on the lake. There are only a few games underway; pucks crack against sticks, the ice groans as it shifts and the cheerful cacophony of kids at play drifts along the wind.

Anthony Mousseau is standing at the side of one rink, frosty balaclava pulled up to his eyelashes, cheering as his six-year-old son, Ares, sporting a Winnipeg Jets jersey, fires the puck.

“Half the team are gone because they’re cold,” Mousseau says, his voice muffled behind the balaclava.

But Ares and the rest of the half-dozen under-sevens still on the ice don’t seem too bothered by the weather — they’re just thrilled to be playing outside.

“It motivates them, they want to go out. It gets them off the electronic devices — rare to see that these days,” Mousseau laughs.

In the tent, 10-year-old Nash Pomehichuk shrugs off the “pretty cold” conditions. This is the Minnedosa minor hockey player’s fourth Skate the Lake tournament, and the part he cares most about is spending the weekend playing among friends.

“You get to play against kids that you know,” he says, listing what makes the event special.

Nash’s mom, Julie Pomehichuk, helped organize this year’s tournament — and played on the championship winning women’s team, Mid Ice Crisis.

There’s something special about seeing “Canadian kids playing on the great big ODR [outdoor rink],” she says. “And our beautiful Lake Minnedosa is the perfect spot for it.”

The outdoor rink tradition, so dear to Canada’s cultural identity, could be under threat, research warns, and the global hockey community — from pond hockey enthusiasts in Finland to the NHL — have been sounding the alarm.

In Minnedosa, despite this year’s event being “colder than we’ve seen for the last several years,” Tanis Barrett says, a month ago, organizers were more concerned about the heat than the cold.

An unseasonably warm December meant the ice on the lake was too thin for town staff — typically in charge of initial ice clearing — to break out the heavy equipment needed to prepare the rinks. The ice was eventually prepared in stages and only completed after colder weather arrived a few weeks before the event.

It’s the mark of a trend seen across Canada and the rest of the global north: warmer, shorter winters are becoming more common and the outdoor skating season is shrinking as a result.

“We’ve lost, in every part of Canada, somewhere between 20 and 40 skateable winter days in your average season,” Orr, the sports ecologist, says.

The most glaring example is Ottawa’s Rideau Canal, a popular skating spot for locals and tourists alike, which has lost about a week’s worth of skating days every decade since the 1970s. The longest-ever skating season on the canal was 91 days in 1971. In 2023, for the first time ever, it didn’t open to skaters at all.

In Manitoba, Winnipeg’s Nestawaya River Trail was only open for skating nine days last winter due to unseasonable warmer temperatures.

It takes at least three days of temperatures below -5 C for ponds, lakes and even backyard rinks to harden enough to safely support skating enthusiasts, Orr says. As Canada feels the effects of climate change — warming at double the global average — those sustained cold spells are fewer and farther between.

“The data that we have uniformly shows that access to natural ice is really steeply declining since the 1990s,” she adds.

Researchers at Wilfrid Laurier University have run a citizen science tool, called RinkWatch, to track conditions on North America’s outdoor rinks for the last decade. The team’s latest report found the winter of 2023-24 was “one of the most challenging and unusual” since the project began, with frequent freeze-thaw cycles and unusually warm early winter weather leading to shorter skating seasons and “especially treacherous” ice conditions across the country.

Climate Central found more than one-third of northern countries, including Canada, lost, on average, at least a week’s worth of winter days (defined as days between December and February where temperatures fall below 0 C) each year in the last decade.

Coastal cities in British Columbia, as well as some parts of Ontario, lost upwards of two weeks of winter days in the same time.

While Manitoba’s typically frigid climate has experienced fewer losses than other regions (Winnipeg lost just one winter day per year), the trend across the global north is worrying for winter sports.

Orr explains hockey participation has been on a downward trend in recent years, in part because it’s an expensive sport made more costly by rising fees to access indoor ice.

“There’s not really an option to play outdoors anymore in the same way that there would have been in generations past, where, yes, there was an indoor rink, but if you were under the age of 10, you probably were playing outside,” she says. “The middle class is getting squeezed out of this sport.”

Orr spoke to Winnipeg-raised former NHL player Colin Wilson for her latest book about the impacts of a warming climate on sport. Wilson remembered honing his hockey skills on ponds and backyard rinks, she says. Now, he worries Canada could lose its competitive edge as a hockey nation as the next generation loses access to those extra hours on the ice.

“Shinny, historically, is a bit of an equalizer in the sport of hockey,” Orr says. “It’s the accessible, low-cost, low-equipment version of the game.”

Back in Minnedosa, most attendees are taking shelter from the extreme winter weather inside the beach pavilion, a cozy, glass-walled room with a panoramic view over the ice below. The room is heated — courtesy of the event’s propane sponsor — and outfitted with a small bar and canteen. Hundreds of people stop by the pavilion throughout the weekend, squished shoulder to sweater-clad shoulder around rows of folding tables. Volunteers stand over steaming crock pots piled high with smokies, pulled pork, baked potatoes and handmade perogies.

“As a family event, it’s pretty amazing,” Laura Lamb, the canteen co-ordinator says. It’s something that brings our community together, but it’s also proof to me that it is an amazing place to live.”

In the midst of the action, Jared McNabb flits from the scorekeeping boards in one sunny corner of the room and a small speaker in another. He’s the tournament’s draw master, in charge of timekeeping, totting up scores and tracking each team’s progression through the championship.

It’s his first year in this volunteer position, but far from his first time in a starring role at Skate the Lake.

McNabb says he can’t remember exactly what year he first played, but “chances are,” it was the inaugural tournament. He was part of a team called the Burgess Quality Dudes, which had, in his words, “a fair bit of success in this tournament.”

From a quick count of the names engraved on the winner’s trophy, the Dudes, as they’re called, won the very first event — and then 10 of the next 15. The team has collected a closet’s worth of the custom jerseys the town designs each year for the championship winners.

“We kind of figured the game out,” McNabb laughs during a brief break between games. “You’ve got to be ready to pass the puck around and deal with some conditions that aren’t 100 per cent between ice and weather, but it’s about having fun and being with your buddies.”

Now that he’s hung up his own skates for the weekend, McNabb is cheering on his two sons as they compete in the under-nine and under-seven games.

“They had a blast and they were happy to be skating on the lake,” he says.

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a reporter covering environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a partnership between The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...