The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Manitoba’s Clean Environment Commission is urging caution — and far more research — before the province licenses a controversial proposal to extract millions of tonnes of silica sand from a freshwater aquifer that serves thousands of residents.

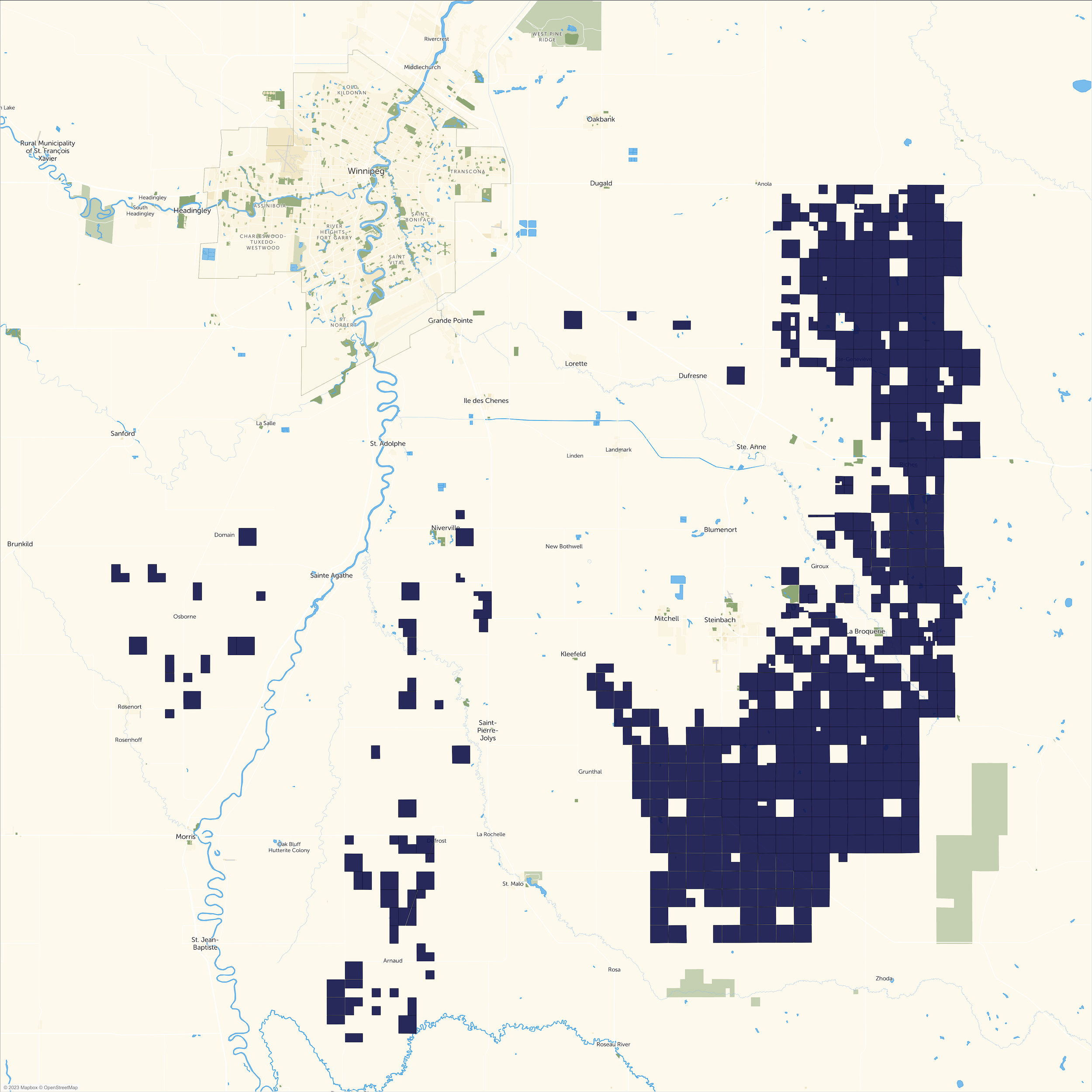

Years of tension and upheaval have surrounded Alberta-based Sio Silica’s plan to extract the grainy mineral — deemed increasingly crucial to green technologies like solar panels — from deep beneath the agricultural fields of the Rural Municipality of Springfield.

A report, produced by the province’s arms-length review body, seems to affirm outcry from hundreds of residents who fear the project hasn’t been fully thought through and could, in a worst-case scenario, permanently damage the region’s primary water source.

Such high stakes and high tensions, the commission decided, should warrant a high standard of review and confidence — something it suggests Manitoba has so far failed to get from Sio Silica.

Because the company plans to employ a new, as-yet unproven method of sand extraction, the risks and uncertainties are more pronounced, the commission says.

Not only does the report take aim at what it perceives as a lack of information from the company, it also points the finger at Manitoba’s licensing process, suggesting the province should be requiring more of companies looking to develop its natural resources — especially for a project rife with unknowns.

While the commission doesn’t go so far as to advise against the licence, to the dismay of some project critics, it does provide eight recommendations to achieve more clarity, oversight and risk assessment before a licence is issued.

Here’s everything you need to know about Sio Silica’s path to production.

Tensions have flared for nearly six years between Springfield residents and the former oil executives behind junior miner Sio Silica as the company ramps up efforts to establish a mining and processing operation just outside of Winnipeg.

Sio Silica claims they’ve found a source of high-purity silica sand (fine grains of quartz sand used in manufacturing semiconductors, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries and other green technologies) buried 60 metres deep in an aquifer that serves communities in Springfield and surrounding municipalities.

The plan calls for drilling hundreds of wells a year in clusters, injecting air and sucking out a mixture of sand and water. This “airlift” method, the company says, is used commonly to drill water wells, but it’s never been used in sand mining. It’s this novelty that’s earned the company enough political attention and pushback to spark clean environment commission hearings.

The extracted sand mix will be piped across the countryside to a processing facility in Vivian, Man., to be washed, dried and loaded onto a new rail loop destined for local and international markets. The excess water will be treated with ultraviolet light and piped back into the aquifer. The company plans to cap and close each cluster of wells before moving on to the next.

Springfield residents adamantly opposed the project from the outset. The sandbar is one layer of the region’s freshwater aquifer and the company plans to leave hundreds — even thousands — of large cavities in this layer as it proceeds. It’s not clear how this will affect the region’s all-important water source.

Residents have echoed the refrain that “water is life” and no risk that could damage freshwater is worth taking.

Equally concerning to residents, Sio Silica has claimed it plans to sell sand to the green tech industry, but a note buried in its proposal suggests up to 40 per cent of the sand could be sold to the oil and gas industry for use in hydraulic fracturing (better known as fracking), contradicting the company’s reported goal of being “the world’s most environmentally friendly silica mine.”

The commission spent three weeks earlier this year hearing from participants, including a slate of technical experts, a consortium of municipal leaders, the company and a group of citizens organized under the banner Our Line in the Sand Manitoba, before delivering its final report.

The commission’s report has been described as “devastating” for Sio Silica’s progress, at least by Our Line in the Sand’s lawyer Byron Williams, speaking to a Winnipeg radio station.

The bulk of recommendations ask Sio Silica to generate more research to back their claim the project will have minimal impact on the region’s land and water.

“Members of the panel are unable to state with confidence that all potential environmental effects of this project have been fully considered and that adequate detailed plans have been prepared for preventing or mitigating these effects,” the commission states.

The commission criticized Sio Silica for presenting too few test results and leaning too heavily on assumptions. For example, the company assumed the layers of limestone, shale and sand would behave roughly the same across the project area, so they conducted just a couple tests to show how the rock and sand would be impacted by drilling and extraction.

In the absence of better data, “the risk of mine failure is difficult to determine,” the commission wrote.

The commission believes Manitoba should not license the project until Sio Silica has better studied the area’s geology, completed larger scale testing and long-term monitoring of those tests, proven the efficacy and safety of its water treatment strategy and developed detailed management and emergency response plans — along with a detailed risk assessment on the probability, consequences and response plan for worst-case scenarios.

The commission has long pushed Manitoba’s environmental approvals branch to request more comprehensive information from applicants before making licensing decisions — particularly when it comes to cumulative effects assessments, which help clarify the scope of environmental and human health impacts. The current guidelines are “limited,” the commission wrote, and do not reflect best practices for environmental assessments.

“Projects with a higher potential for negative impacts and significant consequences require more specific attention and rigorous review,” the commission adds. “The current project under review would have benefited from greater involvement of the regulator early on.”

Before licensing Sio Silica’s proposal, the commission recommends Manitoba appoint a committee of municipal and provincial representatives to monitor project development with shared scientific findings, defined reporting requirements and regular public reports. It also recommends Manitoba take a “step-wise” approach, taking new research, testing and engineering expertise into account before moving forward.

Manitoba’s environmental approvals branch distributed Sio Silica’s proposal to technical advisors from other government departments to gather comments, questions and recommendations. Several branches, including groundwater management, environmental enforcement, infrastructure, wildlife and public health, submitted detailed responses that asked the company for clarifications and outlined the permits and extra licences it will need to move ahead.

The mines branch, however, was conspicuously silent — and that has left both Sio Silica and the province in a tricky position.

Sio Silica will eventually need a licence from the branch to start drilling, but experts who testified during hearings called attention to the fact Manitoba’s mining and well regulations prohibit the exact kind of drilling the company has proposed.

To get to the sandstone aquifer, the company will need to drill through the overlying limestone aquifer and the fragile shale barrier that separates them. Parts of the shale and limestone are expected to crumble, causing water to mix between the aquifers. That’s generated significant concern from experts who believe collapsed rock and dissolved oxygen can cause heavy metals to leach into the water, while blending aquifers can introduce poor-quality water to a clean freshwater source.

Their concerns are backed by Manitoba laws that specifically ban mixing groundwater from the Winnipeg Formation (the sandstone aquifer) with any overlying aquifer.

Sio Silica has argued those rules don’t apply because both aquifers have similar quality freshwater and several drinking water wells in the region already connect the two aquifers. Experts pointed out the company plans to introduce thousands of new aquifer connections, magnitudes larger than the existing wells. The province has yet to weigh in either way.

Given the “understandably” passionate water quality concerns from residents and the vast uncertainty around Sio Silica’s mining technique, the commission’s first recommendation calls for the province to get a legal opinion and issue a ruling on whether this aquifer-mixing breaches its own rules.

Manitoba Environment Minister Kevin Klein received the report last week and promptly released it to the public in light of “significant community and public interest” in the project, but it’s not clear what the government makes of the report’s recommendations.

Speaking to media, Klein — a rookie MLA who was handed the environment file in late January — said his department takes the report “very seriously” and will “adhere to a thorough due diligence process — as we do with every environmental licence application.”

The province has stated next steps will include a detailed technical evaluation of the report’s recommendations and “engagement in meaningful discussions with Indigenous communities.” (The province and company have been criticized by Indigenous communities in the project area for failing to consult with them.)

Sio Silica’s lawyers put out a short statement following the report’s release saying the company is “pleased to move forward with our project as it progresses to the next steps” and committing to “continual research, data analysis, operational improvements, environmental monitoring and partnerships with Manitoba companies.”

In short: no. The recommendations aren’t binding, and the commission has no power over the eventual licensing decision.

Manitoba’s environmental approvals branch has fielded nearly 300 project proposals since the Progressive Conservatives took power in 2016, according to departmental reports. Not one has been refused.

Even as Manitoba promises to strike another technical advisory committee to review the commission’s report, critics have expressed a “crisis of trust” with this government’s handling of Sio Silica’s proposal. Not only does Sio Silica employ several people connected to Manitoba’s Conservative party (including David Filmon, son of former premier Gary Filmon) but behind the scenes, the province’s actions appear to favour the company.

From the outset, Manitoba told Sio Silica to split its licence application — one for the facility that will process and export sand and another for the extraction process. The facility was licensed in December 2021.

This “project splitting” has been widely criticized by opponents who believe it allows the company to minimize the environmental impacts. The commission says it seems “obvious” both elements are “very closely interconnected” and recommended a cumulative effects assessment to understand the environmental impacts of both processing and extraction over the mine’s 24-year lifespan.

Manitoba also chose not to make participant funding available, though it’s typically accessible to public organizations to help secure experts and lawyers for commission hearings. That left citizen groups like Our Line in the Sand to pay their own way. Participants told the commission the lack of funds meant they weren’t able to secure the expertise they had intended.

And just last week a conflict erupted in Springfield municipal council stemming from a provincially appointed board’s decision to override local leadership and strongarm the municipality into changing its zoning laws to accommodate Sio Silica’s processing facility.

All of this comes atop Manitoba’s commitment to strengthen its mineral sector and reduce “red tape” in the name of economic development — as per recommendations from the mining industry.

Sio Silica has pitched itself as an economic launching pad for the province, touting its partnership with a major solar panel manufacturer to suggest the project will help kickstart a local advanced manufacturing industry. (The mine itself is expected to generate just a few dozen jobs.) Manitoba has already licensed an open-pit silica sand mine and solar glass plant, proposed by Alberta-based Canadian Premium Sand, on Hollow Water First Nation territory near Black Island, Man. It would appear the province is interested in developing its silica sand resource.

Ultimately, we don’t.

Project opponents continue to advocate the province scrap Sio Silica entirely, but should a licence be granted it’s unclear how Manitoba intends to mitigate and monitor project impacts.

The commission suggested a monitoring committee with members from outside the provincial government (though they would be provincially appointed), but did not go so far as to recommend specific monitoring timelines or activities, leaving those decisions to the province.

Manitoba’s record on environmental monitoring has been in decline in recent years. When the Conservatives first took office in 2016, the province was carrying out upwards of 150 monitoring activities annually. Last year they completed just 50. While such sharp decline could be in part attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, monitoring had been on a slow decline since the Tories took office. The commission expressed serious concerns about the uncertainties of this “essentially experimental” project, amplified by the fact it involves long-term development in aquifers that serve tens of thousands of homes, farms and businesses in one of Manitoba’s fastest-growing — and drought-sensitive — regions.

The stakes are high, and while the commission states it sees merit in the project, that’s only if “the risks posed to the quality of water … and the management of those risks can be adequately addressed.”

The government said the report has been handed off to Manitoba’s environmental approvals branch, which will be in charge of issuing an eventual licensing decision, but there’s no clarity on the timeline. Klein could also choose to make the decision himself, provided he gives advance notice.

With a provincial election looming this fall, the final decision could be complicated by a possible change in governing parties. Manitoba’s New Democratic Party has urged the government to hold off on a final decision until after the election, but the opposition party has not taken a firm stance on Sio Silica’s proposal.

Klein told media timing wasn’t a concern: “The process will take as long as the process needs to take.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...