Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

This story is a collaboration between The Narwhal and Future of Good.

Making a cheque out to the food bank. Putting coins in the Salvation Army’s bucket at Christmas. Sending money to the Red Cross.

This is what many people in Canada think of when they think of donating to charity.

But for a growing number of wealthy Canadians, donating to charity means something else entirely: investing in a mining exploration company searching for the likes of lithium, copper and uranium and then donating some of those shares to charity.

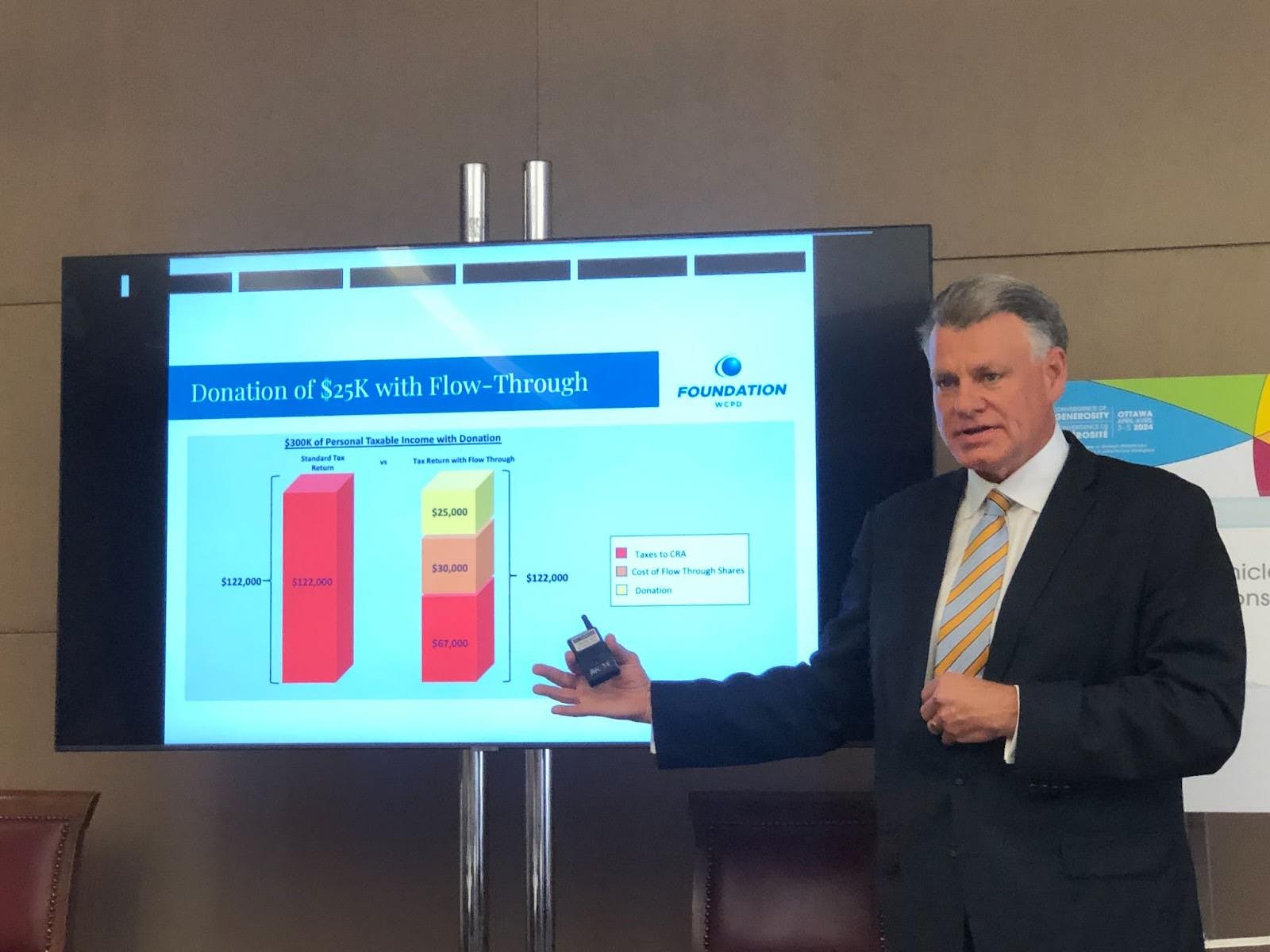

It’s a little-known strategy called “charity flow-through” and it allows wealthy Canadians to reap huge tax benefits.

One prominent Ottawa businessman, Peter Nicholson Jr., president and founder of a firm called Wealth Creation Preservation & Donation, is one of the most vocal proponents of the strategy in Canada.

Nicholson Jr., a self-described “tax reduction” specialist, touts the practice as a huge win for mining companies and charities — and also for the environment.

Many of the companies that have been financed using this strategy are searching for critical minerals like lithium or copper. These substances are deemed crucial for a shift to a greener economy because they help power tools like solar panels and electric car batteries.

To Nicholson Jr., this means the tax-minimization strategy he’s touting is a tool to help “save the world from climate change.”

Environmental advocates and some Indigenous communities, however, say the picture is somewhat more complicated.

This was the subject of a months-long joint investigation by Future of Good and The Narwhal.

Wondering what the heck “charity flow-through” is and what it means for the environment in Canada? Read on.

Essentially, it’s a tax strategy that provides an incentive for wealthy donors to donate shares of mining exploration companies instead of cash to a charity.

It sounds complicated, but the gist is simple. Wealthy Canadians purchase shares of a mining exploration company — then gift those shares to a charity on the same day and reap big tax benefits.

The savings are possible under Canadian tax laws, which allow donors of such shares to benefit from what are known as mining investment tax credits and deductions and charitable donation tax credits.

In a best-case scenario, according to Nicholson Jr., this strategy could allow a Canadian to make a donation worth $100,000 and wind up with a tax break of $99,000.

“It’s practically free,” John Bromley, CEO of the Vancouver-based Charitable Impact Foundation, told Future of Good and The Narwhal in an interview.

While most donors don’t use charity flow-through donations, charitable foundations told Future of Good/The Narwhal that a growing number of wealthy Canadians do.

These anecdotal observations are backed up by Canada Revenue Agency data obtained by Future of Good/The Narwhal. That data shows growth in the volume of donations made to two foundations in Canada that specialize in processing flow-through share donations — the WCPD Foundation (Nicholson Jr.’s foundation) and Conam Charitable Foundation.

For foundations, it can be a boon for fundraising.

Patricia Saputo, a member of the third generation of the billionaire Montreal cheese empire, used the charity flow-through method to make a $5-million gift to the University of Ottawa.

“Using charity flow-through shares has allowed me to give more than I would otherwise been able to give,” she said in a testimonial for Wealth Creation Preservation & Donation.

Executives of three of the top charity flow-through firms say their clients have used the strategy to donate about $1.8 billion to Canadian charities collectively.

It sure seems like it.

Ron Bernbaum, PearTree Canada’s founder and CEO, said his firm’s charity flow-through transactions alone have supported Canadian mining exploration companies nationwide to raise more than $3 billion.

“It’s now the preferred method of raising exploration risk capital,” David LeClaire, founder and president of Oberon Capital, another firm that facilitates charity flow-through donations, said.

Troy Boisjoli, CEO of uranium exploration company ATHA Energy, said his firm has used the strategy because it allows the company to raise the most money while retaining the most shares compared to other fundraising approaches.

“There are not many things that are win-win-win, right? But the charity flow-through structure is one of those,” he said.

Typically, mining exploration companies are not required to secure the consent of Indigenous people on whose treaty or traditional territory they want to explore before beginning work, though some companies have indicated they consult with Indigenous communities.

In B.C., the Yukon and Quebec, First Nations have successfully sued provincial and territorial governments, arguing aspects of this so-called “free-entry” system violate their constitutional rights.

Two similar lawsuits are ongoing in Ontario.

Tensions around the free-entry approach have been exacerbated recently with a shift in some parts of the country from in-person claims staking to digital.

While companies can commonly begin exploration after making a mining claim, more disruptive activities typically require a permit from the provincial or territorial government.

Before a permit is granted, impacted Indigenous nations are often sent information about a company’s exploration plan and given the chance to comment. If objections are raised, the government will sometimes require a change in a company’s plan.

It’s complicated. Take the example of northern Saskatchewan’s uranium-rich Athabasca Basin.

In the past five years, companies exploring the region have collectively raised more than $115 million via charity flow-through financing, according to a Future of Good/The Narwhal analysis.

Garrett Schmidt, executive director of local non-profit Ya’ thi Néné Lands and Resources (YNLR), said the charitable sector’s participation in such financing is a “double-edged sword.”

His organization is owned by the seven Athabasca Basin communities of Hatchet Lake Denesułiné First Nation, Black Lake Denesułiné First Nation, Fond du Lac Denesułiné First Nation and the municipalities of Stony Rapids, Uranium City, Wollaston Lake, and Camsell Portage. While five companies that have raised money via charity flow-through have signed exploration agreements with Schmidt’s organization, ensuring locals benefit from the activity, seven others have not.

When charities help companies who haven’t signed exploration agreements to raise funds, Schmidt said it’s a “net negative” for the community because it impacts the land while locals get little benefit.

Spokespeople for two firms without exploration agreements that responded to requests for comment said they endeavour to develop positive relationships with First Nations people on whose treaty or traditional territories they explore.

Nicholson Jr. and other flow-through share providers emphasize that despite the negative environmental reputation often associated with the mining exploration sector, the industry is green — and a vital part of a clean energy future.

“The greenest community that I’ve ever met is the exploration mining sector,” Ron Bernbaum, CEO of charity flow-through firm PearTree Canada, told Future of Good/The Narwhal. “It’s astounding how concerned they are about the environment.”

But others stress that concerns remain.

Some have raised concerns that exploration can have negative impacts on wildlife.

For example, to search for uranium underground, companies sometimes cut vast metre-wide stretches through the forest to lay sensor cables. The practice provides companies with good data but creates a “wolf highway,” making it harder for caribou to evade their predators. (The companies that responded to requests for comment said their exploration did not harm caribou.)

Then there are concerns about water. Companies commonly drill far beneath the ground to explore for resources.

MiningWatch’s national director, Jamie Kneen, said the activity can contaminate the water if drilling fluid is mismanaged, or if a drill hole connects contaminated and clean groundwater. (Companies that responded to requests for comment said that their exploration didn’t contaminate water or that they never explore near lakes or rivers.)

Kneen said those participating in charity flow-through share transactions should be cognizant that exploration lays the foundation for the development of mines — an activity with a significantly larger environmental impact.

While a company that develops a mine must now commonly raise sufficient funds to cover environmental remediation at the end of the mine’s lifecycle, Leslie Anne St. Amour, interim executive director of Indigenous-led charity RAVEN, said this is not always sufficient in practice.

“Those plans don’t necessarily account for accidents or disaster. Because if they were required to account for that, no one would be able to put up the money for it,” she said.

The Narwhal accepts charitable donations, including in the form of securities, through CanadaHelps. At no point does CanadaHelps disclose the details of the securities being donated. The Narwhal has not knowingly accepted donations of flow-through shares from any mining exploration companies. The Narwhal has not received donations from Wealth Creation Preservation & Donation Foundation or Conam Charitable Foundation.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...