The company that owns the Mary River open-pit iron mine on Baffin Island in Nunavut has been sending different messages — one to regulators and another to potential investors — regarding its expansion plans.

Baffinland currently has approval to ship six million tonnes of iron ore per year from from Milne Inlet, north of the mine. The company’s public plans for an expansion to its shipping capacity show it loading 12 million tonnes of iron ore into ships, via a 110-kilometre railway, in Milne Inlet every year by 2020 or 2021.

But behind closed doors, Baffinland has been distributing materials to potential investors claiming it will increase its capacity 50 per cent higher than that, to 18 million tonnes, as early as 2021.

“Their plan, at least as communicated to bond buyers, is to get authorization to ship 12 million [tonnes] out of Milne and immediately turn around and get approval to ship 18 million [tonnes] out of Milne — something they’ve never told the public,” says Chris Debicki, vice-president of policy development and counsel for Oceans North.

Iron ore is primarily used in steelmaking. Canada is one of the top-producing iron ore countries in the world, producing 49 million tonnes in total in 2017, according to Natural Resources Canada.

Public hearings for the Mary River mine expansion to 12 million tonnes are set to begin in Iqaluit next week.

The company has not mentioned the additional expansion in any of its regulatory submissions.

Media representatives for Baffinland did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Export ships to pass through narwhal habitat

The mine is located on the northern tip of Baffin Island, and is one of the northernmost mines in the world. It exports its iron ore through Milne Inlet to the north.

Ships leaving Milne Inlet pass through Eclipse Sound. Both bodies of water are important for narwhals, a species of special concern in Canada.

Before Mary River, there was no large-scale industrial shipping in the area.

“We actually don’t know, based on any of the research, that shipping even 4.2 million tonnes [its original permitted amount] is a safe threshold in terms of disturbance to marine mammals and a host of other environmental impacts,” Debicki explains. “If you look at the way this mine has ramped up quite quickly over the last five years, I don’t think the science has caught up.”

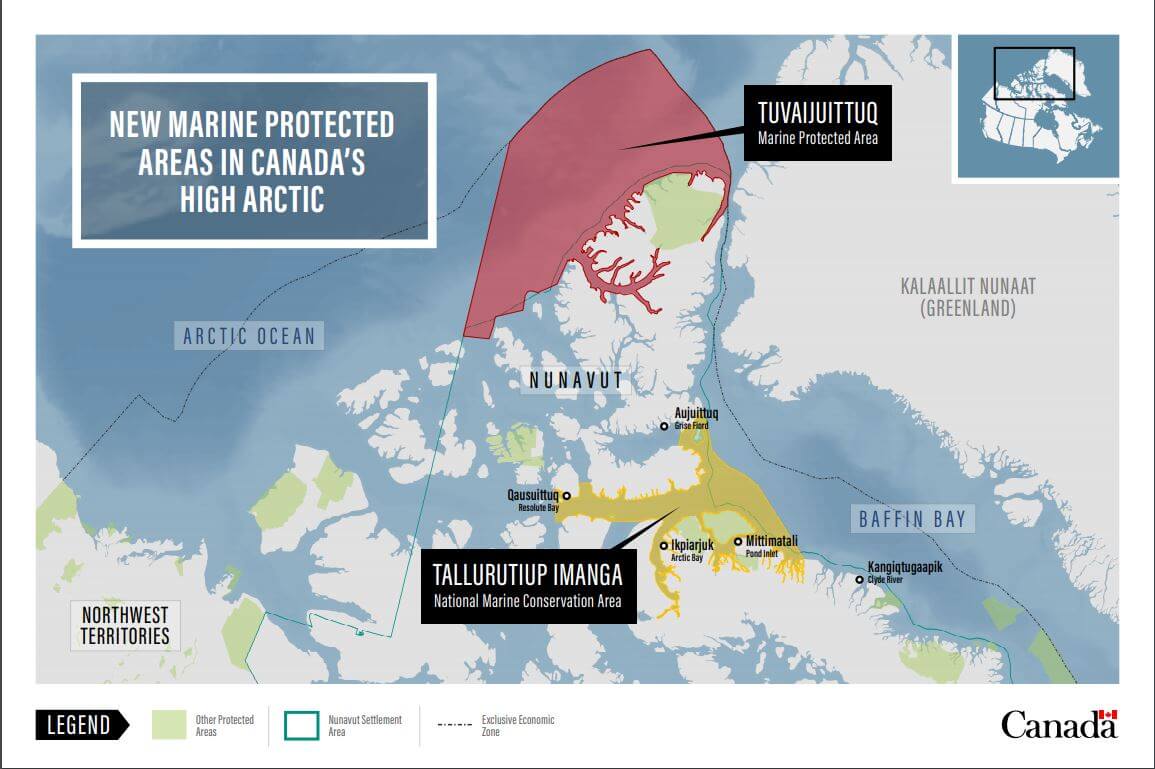

The entire region involved in the shipping from Milne Inlet is part of the Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area, a 108,000 square-kilometre stretch of Arctic Ocean recently designated in recognition of its importance to wildlife, including narwhals.

A map showing the Tallurutiup Imanga Marine Conservation Area. Map: Government of Canada

“That was a collective recognition, led by Inuit leadership, that this area is a spectacular ecosystem, highly productive and of huge cultural importance,” Debicki says. “The incremental increases in industrial shipping really flies in the face of the social and cultural importance, and natural importance of this area.”

The extra iron ore would mean more ships making transits through the sensitive habitat in Eclipse Sound, from around 150 ships per year to “well in excess of 200,” according to a sworn affidavit filed with the Nunavut Impact Review Board by Oceans North researcher Georgia MacDonald.

Those ships generate noise that Oceans North says has already affected narwhal behaviour and impacted traditional Inuit hunting. The Narwhal reached out to the Qikiqtani Inuit Association for comment, but the organization was not able to respond before publication; this story will be updated if and when the association responds.

Ship noise has been confirmed as a cause of stress in marine mammals, resulting in loss of feeding opportunities, social disruption, stranding and other behaviour changes.

The company says it has again requested approval to ship during the early winter months as well as during the summer. Given the sea ice that forms every fall, this would presumably involve using icebreakers, a notion the regulator rejected in 2015.

An investors’ circular shared with The Narwhal shows the larger expansion would be expected to increase profits substantially while shortening the mine’s life by 10 years; it is also expected to decrease the total amount of royalties the company would pay.

“The expected economic benefits from a massive ramp up in production don’t necessarily flow to rights holders, specifically Inuit,” Debicki says.

Documents show expansion work already begun

The port at Milne Inlet, which the company now intends to use to ship millions of tonnes of ore each year, was originally pitched to “only be used occasionally for the delivery of oversized equipment,” the company writes in the investment document.

The conflicting information “undermines a rational environmental impact analysis,” MacDonald of Oceans North wrote in the affidavit.

The investor materials appear to show that the company has already begun work on the expansion. Nunatsiaq News, Nunavut’s paper of record, reported this summer that equipment and buildings for the rail expansion have already been delivered to the site.

The mine has the consent of local Inuit communities, but CBC North reports that that relationship has been fraying lately, with the communities of Igloolik and Pond Inlet saying this summer that traditional knowledge is not being used appropriately. Local employment levels have also fallen far short of what the company promised.

Affidavit of Georgia MacDonald, Oceans North researcher re: Baffinland Mary River mine expansion 28, 2019 by The Narwhal on Scribd