‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

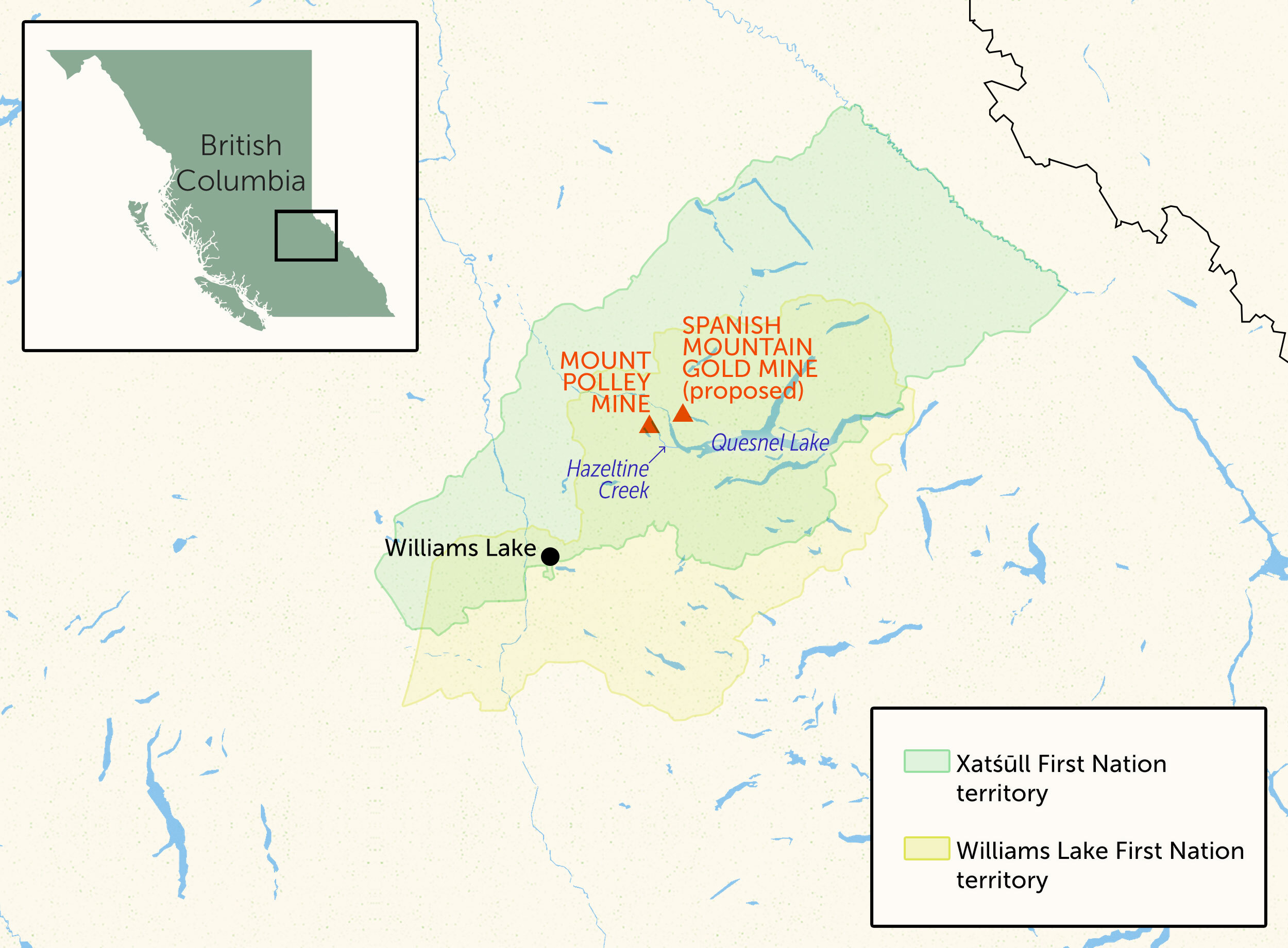

It was eight years ago today when a section of the Mount Polley mine’s tailings pond collapsed, releasing an estimated 25 million cubic metres of contaminated mining waste into B.C.’s Fraser River watershed. Since then, mine owner Imperial Metals won $108 million in a settlement with two engineering firms involved in the tailings pond construction and is, once again, looking to fire up operations following the worst mining disaster in the province’s history.

The spill had a devastating impact on nearby communities as the liquid waste made its way into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek and Quesnel Lake.

“Elder after Elder got up and they were just crying thinking of the effect this was going to have on the salmon and … all the other animals that relied on Quesnel Lake for their sustenance, including us,” said Bev Sellars, who was Chief of Xatśūll Nation at the time of the spill.

An investigation into the breach found poor design that didn’t take into account the glacial silt underneath the tailings facility was to blame for the failure. After the spill, a massive cleanup began and some remediation work still continues today. The mine re-opened in 2016 but closed again in 2019 when copper prices fell.

Now, Scotiabank predicts record high copper prices by 2025 as global efforts to tackle climate change lead to electrification, battery use and infrastructure that demands the metal. B.C. is the country’s biggest producer of copper, accounting for over 53 per cent of all Canadian production, and Imperial Metals is taking its next shot.

The Narwhal wanted to know what has happened since the disaster and what happens when the site of the country’s worst tailings dam failure wants to return to full production. Turns out, it’s business as usual.

According to an annual report, Imperial Metals — the company that was operating the site at the time of the disaster — settled a lawsuit in 2018 against two engineering firms for about $108 million.

“I think they profited from that spill instead of being held accountable,” Sellars said in a phone interview.

Imperial Metals never faced any fines or charges for the dam breach. Years later, two engineers were ordered to pay $132,500 and $94,000 in fines and costs for their role in the dam failure and a third’s professional designation was temporarily suspended.

As for the surrounding environment, the site did undergo remediation and restoration work continues today along Hazeltine Creek. Imperial Metals says it paid $70 million for the cleanup. The company claims no government funding or taxpayer’s money was spent on the cleanup or repair work. But independent economist Robyn Allan found taxpayers paid for almost $40 million of the cleanup in tax refunds and costs incurred by government departments.

After the toxic wastewater was released in 2014, Hazeltine Creek was almost destroyed and looked like a “moonscape,” said Phil Owens, research chair with the Quesnel River Research Centre and professor at the University of Northern British Columbia.

While a lot of work has been done to try and bring the stream back, “it’s nothing like the treed landscape it once was” and will take decades to return to what it was before, he said.

Quesnel Lake — the deepest lake in the province and possibly the deepest fjord lake in the world — still has much of the contaminated sludge resting at its floor. Owens and his colleague Ellen Petticrew, research chair with the Quesnel River Research Centre and professor of geography at the University of Northern British Columbia, were invited to listen to Imperial Metals’ presentations about how they were going to deal with the tailings. A few options were discussed but it was ultimately decided that it would be best to leave the tailings resting at the bottom of the lake, rather than try and remove them.

Petticrew’s research is showing that the contaminants aren’t just sitting at the bottom of the lake, but are mixing up water columns and finding their ways down connected waterways. She’s found concentrations of metal in organisms like phytoplankton and zooplankton — which are food for local fish.

Petticrew estimates it could take decades or even a century for the bottom of the lake to return to some normality without any intervention. Researchers at the University of British Columbia published a study that found tens of thousands of tonnes of small particles remain in the water column and lake bottom today.

Headlines written by the Mount Polley environmental team for the Williams Lake Tribune claim that, “remediation is now complete at Mount Polley.” But Sellars disagrees. “It’s still a disaster there and all of that sludge is still sitting at the bottom of the lake,” she said. “It’ll probably take years and years and years before it runs clear. But then there’s so much mining out there. I don’t know if it’ll ever run clear.”

Despite Mount Polley’s official status being listed as “closed care & maintenance” by the provincial government, there’s a lot going on at the mine site right now, including drilling and blasting.

Petticrew took a tour of the site last week while the mine starts gearing up for full production. She saw the water treatment plant in operation and a pit that’s holding some of the tailings — the byproduct of crushing, grinding and processing mineral ore that’s made up of leftover rock and water, and flooded nearby lakes and rivers in the 2014 disaster. Today, the mine continues to discharge treated wastewater into nearby Quesnel Lake.

Approximately 4.5 million tonnes has already been mined between November 2021 and March 2022, “in preparation for the restart of operations” according to the recent community updates.

Imperial Metals is also purchasing, repairing and upgrading equipment and systems at the site and hiring staff. Once they are in full operation, it estimates the mine will have around 350 direct jobs and 700 indirect jobs.

It’s not uncommon for mines to close and re-open. Commodity prices and advances in technology mean that companies may want to pause then restart operations. When that happens, companies usually have to go through an authorization process.

The Mount Polley mine first opened in 1997 and went into care and maintenance from 2001 to 2005 because of economic reasons.

After the 2014 tailings dam breach, the mine had to apply to the province for permit amendments to restart. “The reason for these amendments was that substantial changes to tailings facility design and management were required and those changes required authorization by the province before they could be implemented,” Sean Leslie, communications director for the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation, wrote in an email.

For the current restart plan, Imperial Metals notified government regulators last year of their intentions to restart mining and milling, the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy and the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation told The Narwhal.

But because the company intends to restart operations within its already “approved mine plan,” no additional approvals are needed under the Mines Act, according to the Ministry of Mines.

The mine has been discharging waste into Quesnel Lake since 2015 and is looking to extend its permit to do so until 2025. A decision on whether the company will be granted this extension will be made by the end of the year, according to the Ministry of Environment, though it doesn’t affect the mine’s ability to restart production.

With two pipes almost constantly releasing treated liquid mine waste into Quesnel Lake, the volume of treated water that’s now gone into Quesnel Lake is likely about the same volume that was unleashed during the spill, said Phil Owens, research chair with the Quesnel River Research Centre and professor at the University of Northern British Columbia.

A study published by Petticrew’s research team showed in 2016 alone, 6.71 million cubic metres were discharged from the pipes into the lake. The Narwhal went through the quarterly community updates for 2021 and totalled the discharge to be approximately 6.72 million cubic metres.

Petticrew and Owens first started working at the The Quesnel River Research Centre years before the spill. After the spill, Owens said they felt a “moral obligation to the community and to the scientific community at large to try and understand what this massive disaster would do on such a unique and pristine landscape.” They’ve been monitoring Quesnel Lake ever since.

Their research centre, on the south bank of the Quesnel River just two kilometres downstream from the outlet of Quesnel Lake, hosts an open house every year. They said most of the conversation there has been dominated by the spill and the discharge that continues to be released into the lake. “There has been a sense from the community and some of the scientists that there are better options,” Owens said.

“I am dead set against any mining at Quesnel Lake,” Sellars said of the restart plan, adding that the lake is one of the largest salmon-producing watersheds in the world.

The discharge into the lake on top of the disaster was a “slap in the face,” said Christine McLean of the Concerned Citizens of Quesnel Lake. While she understands that excess from the mine has to be discharged somewhere, she said she is hopeful there will be more stringent parameters. She’s part of an appeal of the discharge permit and says she wants to see the waste be at least drinking water quality by the time it hits the lake. The decision for that appeal is set to be heard in May 2023. The appeal will likely be heard after government regulators decide on whether or not to extend the company’s current discharge permit to 2025.

But the impact of the disaster reaches far beyond the immediate residents, Sellars said. The trickle down of the spill eventually flows to the Fraser River and then the ocean. “It’s all connected, and you can’t say who is affected the most. It’s all equal. And that’s one thing that people don’t understand; that it is all connected.”

The mine is in the territories of Williams Lake First Nation and Xatśūll Nation. This July, Williams Lake First Nation announced they have signed a renewed participation agreement with Imperial Metals to ensure the nation has a say in the project.

“There is some scrutiny that people attach to this and ask ‘how do you feel being involved with the company that was responsible for one of the largest mining disasters in this country?,’ ” said Kirk Dressler, director of legal and corporate services at Williams Lake First Nation, in a press release. “But the honest to goodness truth is that it’s a more gut-wrenching situation to be sitting on the outside watching what is going on than to be engaged at the table.”

According to the notes from the last community meeting in July, Xatśūll Nation and Imperial Metals have not yet reached a renewed agreement.

When the mine was last open, 27 of 341 full-time and 12 of 42 part-time jobs were held by First Nations people. But Sellars described the positions as “a few token jobs to make it look like we were involved.” And the people who are hired don’t necessarily live in the local community, McLean said. Many who come and work at the mine bus in and out from 150 Mile House, a community 80 kilometres south, McLean said. “We give you clean water, you give us back toxic waste, and you don’t improve our communities in any way at all.”

Petticrew, who has spent the last eight years researching the impact of the spill on the watershed, said some community members feel a mine can be a good thing if done on a certain scale and over a longer timeline. “Why not stretch it out over longer periods, and give more local people jobs?”

Meanwhile, exploration continues around Quesnel Lake. Spanish Mountain Gold is seeking permits and going through an environmental assessment to build an open pit gold mine east of Hazeltine Creek and just north of Quesnel Lake. The project’s website states that despite the Mount Polley disaster, “we believe that there are many significant differences in our proposed tailing design and water/discharge management so that [the] community’s concerns can be adequately addressed.”

But with the environmental precedent set by Mount Polley, and the province’s open-for-business attitude toward mining, McLean worries about the future of the lake. “If Mount Polley is allowed to pipe their discharge into the lake, how are they going to say no to Spanish Mountain Gold?”

Updated on Aug. 9, 2022, at 7:30 a.m PT: This story has been updated to clarify that tens of thousands of tonnes of small particles are stored on the lake bottom or suspended in the water column of Quesnel Lake today, which represent 90 per cent of the small particles that were initially suspended in the lake after the Mount Polley spill.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...