Water is precious — and precarious — on First Nations reserves like this one

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

Richard Smith calls Peachland home. He has since 1947, the year he arrived in British Columbia’s Okanagan region as a four-year-old boy with his parents from Alberta’s oil fields.

As a young man working at a local sawmill to save money for his university tuition, Smith was impressed by the quality of the water that flowed out of the forested valleys behind the community and emptied into Okanagan Lake.

“The water was spotlessly clean,” Smith says wistfully. “Oh, yeah, it was perfect.”

But during the past decade, the retired teacher says, his town’s water has turned perfectly awful. It is often murky and unsafe to drink for months on end.

Now, in a big expense for a small town, more than $24 million is to be spent on a new water-treatment plant to treat the water from Peachland Creek, the town’s primary water supply. The hefty price tag is already $5 million more than originally budgeted and will likely climb higher when a connection is made to carry water to the plant from the town’s backup water supply, Trepanier Creek.

Upon completion, the plant’s filters will, hopefully, screen out the fine sediments that have triggered numerous warnings from public health officials. The water will then be disinfected with chlorine and ultraviolet light to kill pathogens, such as Cryptosporidium, that have caused waterborne-disease outbreaks in the Okanagan and elsewhere.

A 2017 landslide downslope of a logging road, which temporarily blocked Peachland Creek, was an emphatic reminder to the town’s mayor and her fellow councillors that they must act. The slide caused the water’s turbidity, or cloudiness level, to jump far above the threshold that typically triggers boil-water orders.

Sadly, all of this was avoidable, Smith and others say. The forests behind Peachland have been extensively logged, the land mined, cattle-grazed and crisscrossed with roads. Clear-cut logging, in particular, has accelerated in recent years, with potentially serious downstream consequences.

Public-health officials agree that the best way to get water that is the stuff of Smith’s memories is to use a “multi-barrier” approach.

Think of each barrier as a link in a chain.

The first barrier is the land itself — specifically, community watersheds or the lands draining toward a town’s water source. If those lands are kept relatively pristine, the water flowing from melting snow packs and rainfall is naturally filtered and less likely to be contaminated.

The other two barriers are water-treatment plants and the pipes that distribute that water. Take care of barrier one and barriers two and three are easier to maintain.

Peachland’s main water supply comes from Peachland creek. Its muddy waters are seen here flowing into Okanagan Lake. Photo: Will Koop / The Narwhal

The City of New York famously places a premium on barrier one. Its more than nine million residents draw their drinking water from a watershed with three protected lakes and 19 reservoirs. By protecting the lands around those waters, the city continues to operate the largest unfiltered drinking-water system in the United States.

But in numerous community watersheds in B.C., the situation is vastly different. Logging and mining put communities like Peachland and resource industries on a collision course. Multiple use of watersheds is resulting in multiple abuse of water resources, with the communities in harm’s way left to foot the bill.

Will Koop is a Vancouver resident who became active in environmental issues in the 1980s, when the forests surrounding the city’s primary drinking-water reservoirs were being logged.

The stated reason for logging was to clear away “decadent” trees that some foresters claimed posed fire risks.

Fire risks in a temperate rainforest? Koop was baffled. He began surreptitiously hiking through the watersheds. The more he saw, the more he believed the trees consistently targeted for logging were the oldest, biggest, and solidest. Dollars drove the logging — not a desire to protect water quality.

The light that Koop and others shone on that logging eventually forced the Greater Vancouver Water District to halt the practice in 1999 — something that the district could do because it had a 999-year lease to the Crown lands surrounding its water reservoirs, a level of control that is the envy of municipal governments across B.C.

Today, an area the size of 150 Stanley Parks is protected, and local governments link the “ecological health ” of their watersheds to clean drinking water.

After the Vancouver campaign, Koop began to wonder why so much logging was occurring in other community watersheds.

“Community watersheds comprise only 1.5 per cent of the land base,” Koop says. “Yet there is such a frenzy for getting into these places.What’s this all about?”

Koop’s archival research revealed that as far back as 1888, provincial authorities had powers to designate certain areas of public or Crown land as “reserves” that would be “set apart” for special uses such as protecting water.

In old provincial Forest Service files, Koop found maps from the early 1930s identifying the two watersheds supplying Peachland with its water — the Peachland Creek and Trepanier watersheds — as protected reserves. The words “No Timber Sales” were prominently stamped on both maps.

By the early 1970s, almost 300 watershed reserves were formally designated in B.C. and the Ministry of Environment was in charge of the reserves or community watersheds. Logging was supposedly ruled out on all such lands, with only minor exceptions allowed in cases where watersheds had not officially been designated as community water supplies.

But Koop found that despite such protections, logging did occur in many watersheds, including steadily increasing logging upstream of Peachland. The Ministry of Forests had effectively taken over control of community watershed lands. They were there to be logged, and in many cases they were.

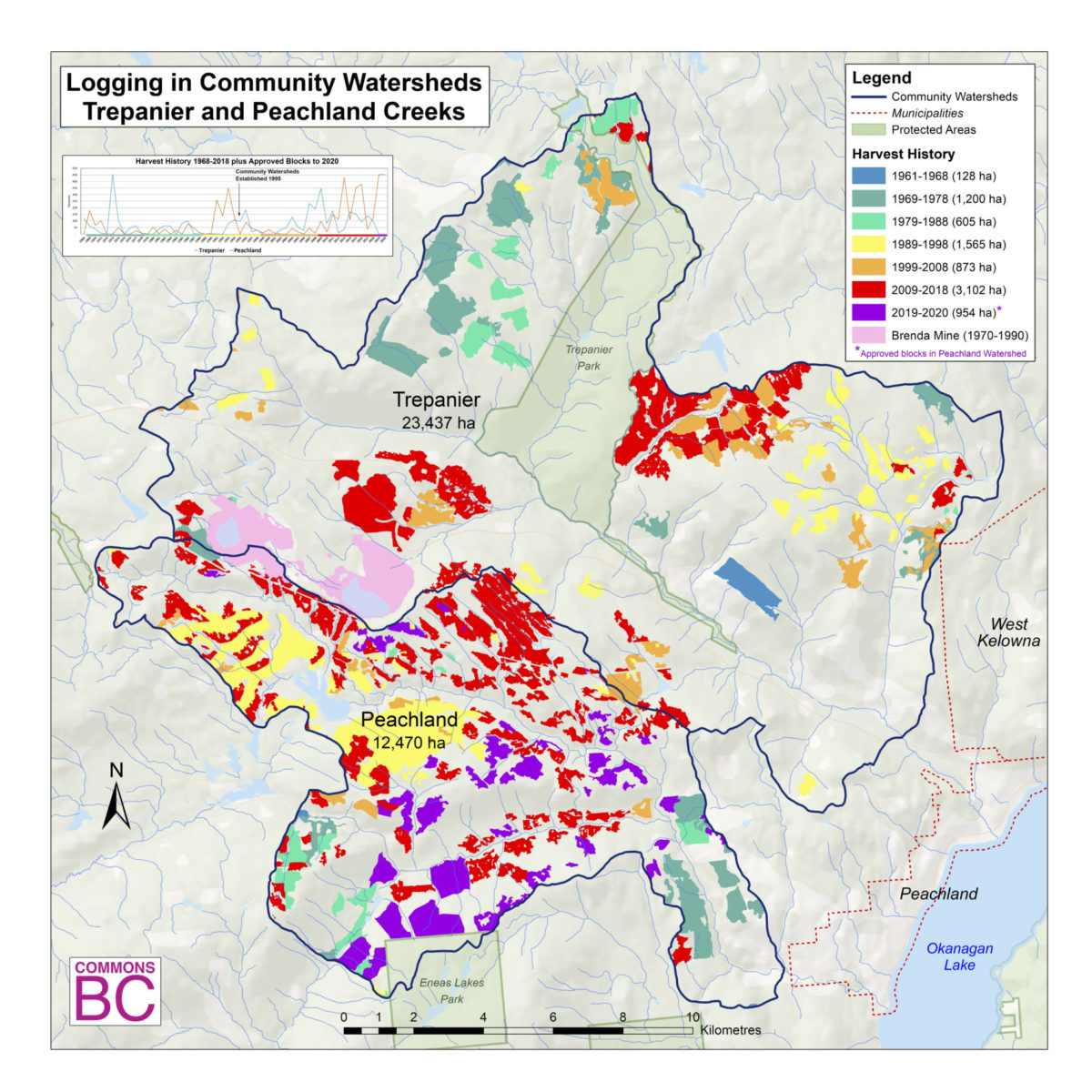

Cumulative logging activities in Peachland’s watersheds have degraded the quality of drinking water. Map: Dave Leversee

Taryn Skalbania moved to Peachland in 1991 from the West Coast, where she was used to high-quality water and communities that took watershed protection seriously.

When Skalbania first arrived, she found Peachland’s water fine, if somewhat unremarkable.

But by the early 2000s, there were days when the water was noticeably murky. By 2012, the water coming out of her taps stayed that way for weeks on end. Then the time span shifted again — this time to months.

That grim reality, among others, prompted Skalbania to become co-chair of the Peachland Watershed Protection Alliance, a co-spokeswoman for the BC Coalition for Forestry Reform and a steadfast critic of land-use decisions in her community’s watersheds.

Taryn Skalbania stands in front of the Deep Creek Water Treatment Plant on McDougald Road in Peachland. Photo: Travis Oleniak / The Narwhal

In all of the years of boil-water advisories, 2017 stands out. That year, flooding occurred in many communities bordering Okanagan Lake. High runoff in Peachland’s watersheds also triggered devastating landslides that sullied the town’s water for months on end.

“Dirty water, historically, for freshet for two weeks is one thing,” Skalbania told The Narwhal. “But mudslides that disable the entire town’s water is another.”

The severity of events that year convinced many that clear-cut logging was at least partly responsible for what had unfolded.

“They contribute to how the water comes off of the mountain. They contribute to flooding. They contribute to the degradation of our water,” Chris Eneas, a Penticton Indian Band elder, said of the clear-cuts, which he saw firsthand during a field trip to the watershed in late March during World Water Day.

Many of the clear-cuts were at high elevations, where heavy snowpacks accumulated due to the lack of trees — precisely the same conditions that residents in the southern British Columbia community of Grand Forks believe contributed to the severe floods that beset their community last year.

In Peachland’s case, all the added water helped to trigger mudslides in 2017 that damaged the drinking-water intakes in the two watersheds supplying the community. Repairing the intakes cost more than $260,000, a drop in the bucket compared to the hefty $24-million-plus water-treatment project now underway.

But Skalbania notes that even the best water-treatment facilities cannot cope with water that is too dirty. Underscoring that point, every single water system in the Okanagan had at least one boil-water advisory in 2017, she notes.

If communities hope to keep such events to a minimum, there’s one sure way to do it, Skalbania says.

“Better source protection. It’s a no-brainer. Just ask Vancouver, Victoria, Portland, Seattle, New York.”

All the cities Skalbania mentions have protected water sources.

Brian Horejsi is another transplant to the Okanagan region. After living and working for years in the Calgary area, he now calls Penticton home.

An expert in large-mammal behaviour, Horejsi was contracted by the Valhalla Wilderness Society to study grizzly bears in the Granby wilderness near Grand Forks. What he found was a watershed so pockmarked by roads and clear-cuts that it had become unsuitable habitat for an iconic wildlife species that defines wilderness in the province.

What baffles Horejsi is that those same activities occur regularly in community watersheds, even though such lands represent a tiny fraction of B.C.’s land base.

“I don’t think there’s any question they should be protected.” Horejsi says. “One-and-a-half percent is inconsequential when you look at the big picture. And the big picture is that those lands are of huge importance for the vast majority of people living in the province.”

“I don’t think there’s any question they should be protected.”

In 2014, B.C.’s independent Forest Practices Board released an investigation of forest practices in community watersheds. The board found that between 2006 and 2014, logging occurred in 131 community watersheds. But some community watersheds were hit far harder than others. Fully half of everything logged in those 131 cases occurred in just 10 watersheds. One of those unlucky 10 did not surprise Skalbania. It was the Trepanier.

The board found that the accelerated logging was a result of the provincial government encouraging companies to aggressively clear away forests that had been attacked by mountain pine beetles.

Skalbania called that finding particularly troubling. In the name of responding to one alleged disaster, the government and industry created another.

“They always have what they call these disasters. ‘Hey, you’ve got a disaster in your back yard and we’ve got to come and clean it up,’ ” Skalbania says. “But they’ve ruined my water.”

Tanya Skalbania at the site of a landslide that polluted Peachland’s drinking water source from Peachland Creek. Photo: Travis Oleniak / The Narwhal

The Forest Practices Board found disturbing evidence that logging companies did not adequately consider what impact their cumulative actions would have on water resources. The board noted that the companies often relied on accredited professionals to address water concerns — yet of 31 professional assessments studied by the board, not one “fully evaluated” the “cumulative hydrological effects” of logging operations in community watersheds.

One year later, B.C.’s auditor general released an audit of the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations’ efforts to manage cumulative impacts. The audit concluded that the government did not give the ministry “clear direction or the powers necessary to manage cumulative effects when deciding on natural resource use”. The audit also found that the government did not give the ministry “explicit” direction on how “to manage cumulative effects when authorizing the use of natural resources”.

Like many First Nations, the Westbank First Nation watched for decades as the B.C. government turned over vast areas of forest to logging companies while failing to do the same for Indigenous peoples.

“A lot of our members had to go up north to find work,” says Dave Gill, a forester and general manager of Ntityix Resources, a Westbank First Nation-owned company.

After much effort, the Nation received a pilot licence in the mid 2000s that eventually became its own long-term community licence in 2009. That licence, combined with an anticipated woodland licence, means the nation has rights to log a combined 80,000 cubic metres of timber per year — enough to keep roughly 30 members employed.

But the lands the government granted Westbank First Nation forestry rights to lay within a number of community watersheds including the Bear Creek, Trepanier, Peachland, Rose Valley and Power’s Creek areas.

That decision meant that in addition to being logged by the First Nation-owned company, Peachland’s watersheds also faced impacts from logging and roads built by the two largest logging and milling companies in the region — Tolko and Gormon Bros. — as well as BC Timber Sales, essentially an arm of the provincial government that auctions tracts of forest to companies that then do the logging.

In its investigation, the Forest Practices Board flagged concerns with logging roads, in particular.

When water courses down roadsides and ditches, it transports large amounts of sediment. That muddied or “turbid” water increases the risk “that pathogens from wild and domestic animals (e.g. livestock) and human sources will attach to the fine sediment particles,” the board concluded.

“When water from the watershed reaches the intake, it must be treated so it is safe for human consumption. If the water is highly turbid, the treatment of water through ultraviolet light, chlorination, and/or filtration is less effective.”

Over the years, Skalbania has learned to appreciate better than most what that means. Water treatment does not guarantee water protection. If you fail to protect your watersheds, you increase the risk that water cannot be properly treated.

In March 2017, a slope below a logging road used by Gormon Bros. failed. It blocked the main creek supplying Peachland with its water. A new channel had to be dug for the stream so that the water could once again flow to the water plant. The slide and rechanneling of the creek meant months of bad water and boil-water orders.

In November of that year, local residents had had enough. They filed a complaint with the Forest Practices Board alleging that decades of logging and road-building had damaged their watershed.

Skalbania and others believe that the cumulative effect of all that logging degraded their water and that the simplest, most effective way to improve the situation is to halt the logging all together.

“If taking the tiny 400 square kilometres of our two Peachland watersheds from the entire provincial Allowable Annual Cut in order to protect the health of our ecosystems and in order to secure our water quality, quantity and timing of flow is not doable,” Skalbania says, “then the entire forestry management system in the province is flawed, fragile, a house of cards.”

The Narwhal contacted the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development to ask if B.C.’s chief forester has powers to lower logging rates also known as the “Allowable Annual Cut” in areas of the province to protect community water supplies.

In an emailed response, the ministry’s communications director Vivian Thomas said: “The chief forester cannot make land use or forest management practice changes where other decision makers have the statutory authority to do so.”

One of the most important “statutory authorities” is the Minister of Forests himself. Forests Minister Doug Donaldson can provide “explicit” direction to the chief forester and others on how to manage cumulative impacts.

Such explicit direction could have a big impact on how much more forest is logged in Peachland’s watersheds in the coming years, including logging that is under the provincial government’s direct control through BC Timber Sales.

In the next five years, Donaldson’s ministry says, 240 hectares of forest is slated to be logged in the Peachland watershed through BC Timber Sales timber auctions. That is six times more logging than has ever happened in the watershed under the auspices of such auctions.

In the meantime, the logging companies that historically did the lion’s share of logging in the watersheds have all approached Skalbania and others saying they want to log more as well. But with a twist. Rather than clear-cutting away all the trees, they now propose to selectively log some forests. The logging will allegedly protect the community from wildfires.

Clearcut activity in the Peachland area. Photo: Travis Oleniak / The Narwhal

Smith says selective logging is precisely what should have happened all along. As a young man working in the sawmill, Smith knew that the big fir logs running through the mill where he worked all originated from selectively logged forests. Ironically, there was nothing altruistic about the industry’s choice then or now.

Selective logging has been practised in the continent’s interior fir forests for a century. Such forests tend to be filled with fir trees of differing ages and heights. Selectively logging some of the bigger trees while leaving others behind to grow bigger is just a smart thing to do.

If the industry had stuck with that plan and not embarked on accelerated clear-cutting of the region’s pine forests as well, things may have been okay, Smith says.

Effectively, what the industry now says is that it will clear-cut fewer pine forests but rapidly increase the selective logging of fir trees. It’s a proposal that leaves Skalbania feeling cold.

“Tolko, Gormon and the Westbank First Nations have all come to us to say: ‘Hey, let’s sit down at the table. Let’s talk. We want to selectively log your watershed.’ Well, we’ve been asking for selective logging for years. Some of us have been asking for it for the last 30 years. And they weren’t interested. They told us many times to our face that it’s just not affordable.”

The year before the big slides that underscored the fragility of their community watersheds, Peachland’s mayor, Cindy Fortin, and her fellow councillors voted in favour of sending a resolution to the upcoming Union of BC Municipalities conference, the annual gathering of municipal-government leaders from across the province.

The resolution noted that “water is a public trust” and that protecting and controlling water resources “requires adequate tools to enable local authorities to enact measures for protection of watersheds”.

The resolution, which passed, called on the provincial Ministry of Environment to “expedite” giving local governments more powers to control events in their watersheds, including powers to issue logging approvals.

But if local residents thought that resolution signalled the council’s support for a halt to logging in the watersheds, they were mistaken.

On the recent World Water Day tour of the watersheds, Fortin told a local television station that a “moratorium” on logging was far too “lofty” a goal. “Collaboration” between logging companies was what was needed, she said.

In the meantime, the resolution passed by the Union of BC Municipalities is in limbo. According to a brief submitted to Peachland’s council in August 2017, the Ministry of Environment will not be acting on Peachland’s resolution any time soon.

“The ministry states its work will ‘take several years to accommodate the broad and balanced engagement with those who may be affected,’ ” the brief stated.

To Skalbania’s ears, that sounds an awful lot like a recipe for more talking and more logging.

“We cannot afford to wait two or three more years,” she says. “What will be left?”

This article was produced in partnership with the Small Change Fund.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

On the election trail, Canada's federal leaders are pushing military and industry in the North....

President Trump’s threats towards Canada carry great risks to Americans as well, and to the...