5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

For years, Jean-Charles Piétacho has been growing increasingly worried about the state of the planet’s oceans and whether they can continue to sustain traditions that have lasted for generations.

Piétacho is chief of the Conseil des Innu de Ekuanitshit, which lies on the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, just above Anticosti Island, and is also known as Mingan.

The Innu say they have used and occupied the estuary and the gulf as well as its north shore since time immemorial. They say their relationship with Uinipek (the sea), the source of life, is fundamental for their maritime people who continue to exercise their ancestral rights, notably the gathering of marine resources for social, ceremonial purposes and for sustenance.

But Piétacho also believes the ocean represents much more than that for everyone.

“We all need the quality of water that was given by the Creator,” Piétacho told The Narwhal in an interview.

Chief Jean-Charles Piétacho of the Conseil des Innu de Ekuanitshit says new rules permitting exploration in Newfoundland’s offshore could have damaging impacts on his community on the north shore of the St. Lawrence. Photo: Francis Vachon / The Canadian Press

Chief Jean-Charles Piétacho of the Conseil des Innu de Ekuanitshit says new rules permitting exploration in Newfoundland’s offshore could have damaging impacts on his community on the north shore of the St. Lawrence. Photo: Francis Vachon / The Canadian PressHis community of 650 people is worried about the threat posed by oil and gas. The industry is lobbying for more exploration, while a new policy allows certain offshore exploration projects to be approved without adequate federal oversight, nor consultation with affected First Nations.

The Innu and their allies allege that a trove of more than 3,000 pages of recently released federal documents reveal how federal and provincial cabinet ministers rigged a regional study that was supposed to examine the safety of oil and gas exploration in an area off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. They say the documents show that the plan from the outset was to reduce federal oversight and allow more drilling projects to proceed, favouring industry interests over scientific evidence.

In effect, companies can now do seismic testing, install drilling platforms or drill wells into an area of the seafloor of the Atlantic Ocean without getting approval from the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. It’s a win for industry which, along with the province, had argued federal assessments were an obstacle to development in a sector that’s critical to Newfoundland and Labrador’s economy.

Piétacho’s community is more than 1,000 kilometres away from this area off the coast of Newfoundland, but a dwindling number of Atlantic salmon swim the route between the two every year.

Atlantic salmon, which the Innu call ushashameku, are listed as endangered around Anticosti Island and of special concern along the North Shore and further down the St. Lawrence River. Salmon enter the river and Bay of Fundy to lay eggs; their young, known as smolt, swim up the river and out of the bay, migrating through the Atlantic and North Atlantic. Fishing ushashameku is particularly important to the Innu and represents a way of life based on spirituality and respect.

Along with valuing the ocean’s cultural significance, Piétacho said, his nation operates a handful of commercial fishing boats, catching Atlantic salmon, crab, lobster and scallops and creating local jobs.

The health of these waters is critical to the people who rely on them.

It’s the reason the Innu of Ekuanitshit intervened in a 2021 court case brought forward by the environmental law charity Ecojustice, representing Sierra Club Canada Foundation, World Wildlife Fund of Canada and Ecology Action Centre. The complainants wanted a judicial review of what they call a “flawed” process that led to this weakened oversight.

In December, Justice Richard Bell denied the judicial review. Ecojustice and the three environmental organizations have appealed this decision. And now, the nearly 3,000 pages of documents released through the court case give a behind-the-scenes look at what happened as the Trudeau government lifted the requirement for federal environmental assessments of oil and gas exploration in a portion of Newfoundland’s offshore — at a time when it told the public it was improving oversight.

Criticizing former prime minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government for watering down the longstanding Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, Justin Trudeau headed into the 2015 election with a campaign promise to improve federal oversight of major projects and restore public trust in federal regulatory reviews.

As prime minister, Trudeau and his Liberal government made good on this promise with the Impact Assessment Act, which came into force in 2019. The Act was meant to strengthen environmental assessments, with a particular emphasis on regional assessments. Studies of existing and anticipated projects are meant to go beyond “project-focused impact assessments to understand the regional context and provide more comprehensive analyses to help inform … future impact assessment decisions,” said Nancy Macdonald, spokesperson for the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, in an email to The Narwhal.

The act has been challenged in court by industry-friendly politicians who say it infringes on provincial jurisdiction. Environmentalists have said that, while it made some much needed improvements, gaps remain. But, in general, the act is seen as an environmental step forward.

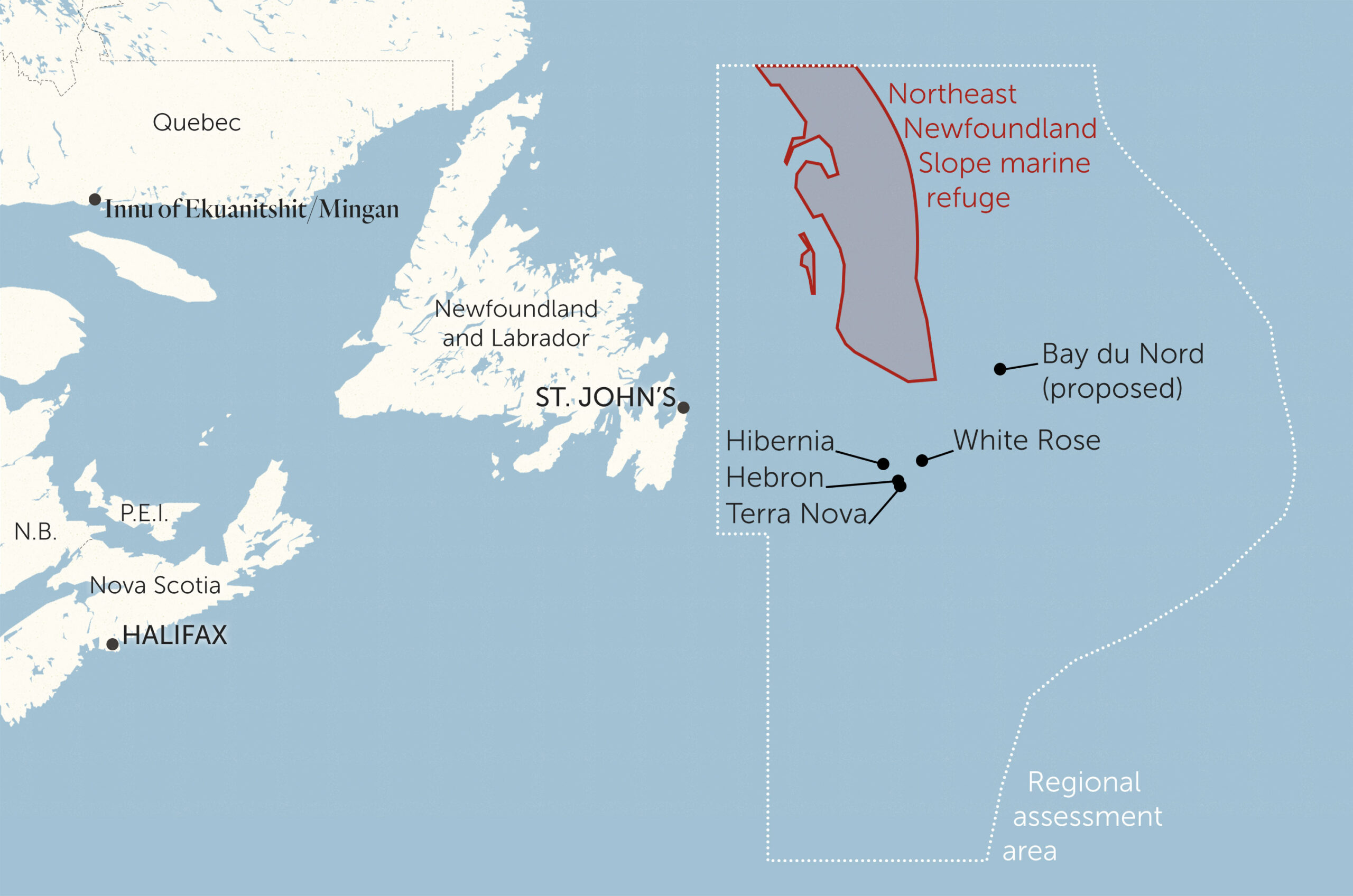

In April 2019, as part of a plan to promote offshore drilling, federal and provincial cabinet ministers announced the creation of the Regional Assessment Committee, saying they had appointed five people to study the regional implications of drilling for new oil deposits east of Newfoundland. At 735,000 square kilometres, the study area is larger than Alberta, stretching from the northern tip of the island of Newfoundland to beyond the southern tip of Nova Scotia — though well off its eastern coastline. There are already four oil-producing projects within the area, with a fifth proposed. Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault is due to make a decision on the controversial Bay du Nord deep-sea drilling project by April 13.

The Regional Assessment Committee was led by co-chairs Garth Bangay, an environmental consultant and previous program manager under Environment Canada, and Wes Foote, an engineer and former deputy minister of Petroleum Development under the Newfoundland government, as well as a board member of the Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board. At the time the committee was established, the government said it would be tasked with writing a report providing advice on how to make the licensing process more efficient for new exploratory drilling projects in the area while also protecting the environment.

This look at Newfoundland and Labrador’s offshore exploration is the first regional assessment conducted under both the Impact Assessment Act and the previous assessment act. “It is precedent setting,” said Sigrid Kuehnemund, vice-president wildlife and industry with WWF-Canada, adding that’s part of the reason it was so critical it be done properly. Based in St. John’s, Kuehnemund said, “It sets the bar for the conduct of all future regional assessments.”

She was among those in the environmental movement who had hopes that the committee would engage the public, address cumulative impacts of development and identify areas that needed protection within the regional assessment area.

But the documents, released through the court battle, show numerous instances in which some federal officials appear to have influenced the Regional Assessment Committee’s review and recommendations to ensure they favoured the industry’s desire to get faster approvals with less oversight.

One example is a letter signed in December 2019 by Seamus O’Regan, who at the time was the federal minister of natural resources. He sent the letter in response to a request from the committee for more time to complete its work.

In the letter — which he also sent to the federal environment minister, the Newfoundland and Labrador premier and the provincial natural resources minister — O’Regan wrote that in order to ensure Newfoundland and Labrador would support the passing of the Impact Assessment Act, the Trudeau government had made a public promise to “exempt” exploratory drilling from federal review.

The province has its own publicized goal of seeing 100 new wells drilled in Newfoundland’s offshore by 2030 and saw regulatory uncertainty and federal climate change legislation as two major barriers.

O’Regan is Member of Parliament for Newfoundland’s riding of St. John’s South—Mount Pearl, as well as the current minister of labour. In that December 2019 letter, he agreed that the government needed to grant an extension to the Regional Assessment Committee’s deadline — provided it didn’t jeopardize industry plans to spend more than $7 billion on oil and gas exploration in deep water.

With an extension granted, O’Regan said the Regional Assessment Committee would be able to complete consultations, including with Indigenous groups, and prepare its final report. “However, the extension must not put at risk the commitment to have a ministerial regulation in place by the end of April 2020 to exempt exploratory drilling activities under the Impact Assessment Act,” the letter reads.

O’Regan’s office declined a request for comment from The Narwhal due to the appeal currently before the court. The provincial Department of Industry, Energy and Technology denied a request for an interview for the same reason.

The office of federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault referred questions to the Impact Assessment Agency, as did his department, Environment and Climate Change Canada.

After the federal government agreed to extend the review, the committee submitted its draft report in January 2020, seeking feedback from stakeholders.

The Newfoundland and Labrador Oil and Gas Industries Association was among those providing comments in an April 2020 submission regarding the industry’s exemption from federal assessment when doing explorations. It said it believes “that for the offshore oil and gas industry to continue to be successful it must be globally competitive, and this must include regulatory processes. Environmental reviews can be undertaken in a fashion that protects the environment but allows economic activity to occur in [a] timely manner.”

Macdonald, with the Impact Assessment Agency, told The Narwhal, that recognizing the provincial government’s interest in the exemption, “the Government of Canada was happy to work with them through an agreement on a regional assessment with the regulatory exemption as a potential outcome.”

The potential for other outcomes than a blanket exemption is what Ecojustice lawyer Ian Miron said kept his clients at the table.

The court documents also include government notes from a meeting in May 2019 between the Regional Assessment Committee and fisheries groups and environmental organizations — including the parties to the 2021 lawsuit. The notes show that participants were concerned that the overarching regional assessment would be used to facilitate further drilling by replacing the need for detailed, project-specific assessments.

According to the notes, the Regional Assessment Committee responded in the meeting that the intention was to “increase efficiency” in the environmental assessment process and bring new information to the table to make the best decisions possible. “The purpose was not to facilitate exploratory drilling,” the committee stated.

Chief Piétacho warns that the reduced oversight may lead to tragedy for local marine life in the event of an accident.

He fears it could be worse than the blowout of an exploratory well in the Deepwater Horizon disaster on the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Deepwater’s failed well was drilled below 1,500 metres of water in the gulf. While some areas of Newfoundland’s eastern offshore wells are far shallower, others reach comparable deep-sea depths — the Bay du Nord project, for example, is eyeing depths between 1,000 and 1,200 metres. The Bay du Nord project has already completed some exploratory drilling and may soon begin production, if approved by the federal government.

In its review of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, a national commission reporting to the president of the United States noted that “deepwater drilling brings new risks, not yet completely addressed by the reviews of where it is safe to drill, what could go wrong, and how to respond if something does go awry.”

Several oil spills in Newfoundland’s offshore in recent years have had experts calling for increased regulatory oversight of the industry. In particular, the worst spill in the province’s history saw the release of 250,000 litres of crude oil from a flowline to Husky Energy’s SeaRose vessel — part of the White Rose project — as it restarted production during a storm.

Although the federal government has removed requirements for federal assessments of offshore exploration in the region, Fisheries and Oceans Canada still has the power to review aspects of new exploration projects that impact fish, fish habitat or species at risk, to ensure mitigations are in place.

And projects within the regional assessment area will still be submitted to a review by the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board, which is jointly managed by the Canadian and Newfoundland and Labrador governments, and which Regional Assessment Committee co-chair Foote sits on the board of. The offshore petroleum board’s role is to ensure that companies adhere to any conditions set out by the regional assessment.

Lesley Ridout, a board spokesperson, said that it publicizes all expressions of interest in new exploration licences in Newfoundland’s offshore. “When we do so, Indigenous groups, the public and stakeholders are welcome to submit comments for consideration on any portion of our land tenure process, as stated in each news release, announcing any call for nominations or call for bids,” Ridout said.

Two industry groups, the Newfoundland Oil and Gas Industries Association and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, emphasized the importance of the regulatory role played by the offshore petroleum board.

“All proposed offshore projects will continue to go through one of the most rigorous review processes in the world,” wrote Paul Barnes, director of Atlantic Canada and Arctic for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, in an emailed statement. “The regional assessment creates a more efficient process and will ensure the federal Impact Assessment is able to focus on the most important project reviews while relying on the world-class expertise of the offshore petroleum board.”

While the documents released as part of the Ecojustice case show how senior government officials like O’Regan advocated for reducing federal oversight of offshore oil exploration, they also reveal that some public servants expressed concerns about the quality of the Regional Assessment Committee’s work.

For example, officials at Health Canada with expertise on environmental assessments said the Regional Assessment Committee’s recommendations failed to address the potential dangers of chemical mixtures deployed by industry to disperse spills.

“Therefore, in the event of a spill in which dispersants are used, there would not be a comprehensive understanding of what potential contaminants may be present that could impact the food chain and potentially pose a risk to human health,” wrote a Health Canada environmental assessment specialist in a February 2020 email to a colleague at the Impact Assessment Agency.

The federal health department recommended that companies be required to proactively disclose the chemicals used in dispersants, which are otherwise proprietary, so that scientists can do sampling to review baseline conditions and any changes in the presence of these substances in the ecosystem. Without knowing which contaminants are involved, Health Canada noted their ability to respond to contaminants that have been added is significantly limited.

Despite Health Canada’s recommendations, the Regional Assessment Committee recommended only that baseline conditions and monitoring take place.

The email thread shows that a manager from the Impact Assessment Agency responded that he agreed with Health Canada and had also pointed out the oversight to the committee, “but this is where they landed and what they ended up going with.”

Macdonald, the agency spokesperson, said that Health Canada’s input helped inform the recommendations made by the Regional Assessment Committee. She noted that the potential effects of contaminants, both from planned oil and gas activities and in the case of a spill and cleanup, are considered in several places in the committee’s final report, including risks, mitigation measures and spill response planning.

However, the report does not mention requiring companies to disclose a list of potential contaminants used in dispersants.

In another instance, Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat concluded that some of the Regional Assessment Committee’s initial work was neither reliable, nor credible after scientists at the federal department reviewed sections of a draft report focused on sensitive areas and species in the marine ecosystem, including plankton, invertebrates, finfish, marine mammals and sea turtles.

The federal department also said after concluding its review in the fall of 2019 that it found “multiple mischaracterizations and/or omissions of available research from the referenced literature” and that “reported baseline information was incomplete and outdated” in most of the sections it was allowed to review.

In an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal, Fisheries and Oceans Canada said, “the committee made substantial additions and revisions to the initial draft” sections that it reviewed, and that its comments and revisions were included in the final report.

Fisheries and Oceans also said that the federal government had committed to regularly reviewing and updating the regional assessment as new science and data become available, which the department would contribute to.

However, Fisheries and Oceans has come under fire itself recently for how its scientific advice is being tampered with — including through the regional assessment process.

In late January, CBC reported on a leaked letter from the union representing Fisheries and Oceans scientists in Newfoundland and Labrador, which outlined its members’ concerns about breaches of the department’s scientific integrity policy due to the influence of industry lobbyists, department leaders and politicians. The letter stated that an investigation by the Office of the Ombuds into a complaint over the regional assessment process “did not follow due process and left members feeling that their complaints were not heard or believed.”

While the Regional Assessment Committee brushed aside some expert advice on its own, the court documents also show at least one instance when a public servant from Natural Resources Canada appears to have pressured the committee to change recommendations that might slow down or prevent oil and gas exploration.

In November 2019, before the committee’s draft recommendations were released to the public, the official emailed a list of concerns to the Impact Assessment Agency.

One of those concerns related to a recommendation that would require a federal review of any proposals in sensitive designated conservation areas, such as the Northeast Newfoundland Slope marine refuge, an area about the size of Nova Scotia that is closed off from commercial fishing due to its abundance of slow-growing cold-water corals and sponges, which provide habitat for numerous species. Protecting the area is a long-standing concern of several of the stakeholder groups, including the environmental organizations represented by Ecojustice.

The Natural Resources official noted that this proposal “could result in few exploratory projects being exempt” from federal oversight, running counter to the Trudeau government’s commitments to the province.

And indeed, the need for a review is not included in the Regional Assessment Committee’s final report, which reads that exploration drilling within marine refuges or certain fisheries “should be contingent on the operator demonstrating that any risks to intended biodiversity/conservation outcomes of that area will be avoided or mitigated.” This runs counter to the federal government’s inclusion of the Northeast Newfoundland Slope in a list of areas relevant towards meeting its goal of 25 per cent protection of Canada’s oceans by 2025 and 30 per cent protection by 2030. At about 55,000 square kilometres, it accounts for about one per cent of the government’s current level of just under 14 per cent protected marine area.

Ecojustice lawyer Miron said the original recommendation was never disclosed to stakeholders and his clients only learned it had been changed after the government disclosed its records through the court case.

Macdonald, from the Impact Assessment Agency, said, “The report and recommendations underwent several iterations,” based on analysis and engagement throughout the drafting process.

Justice Bell sided with the agency in his ruling, noting “There was nothing untoward in the committee consulting [Natural Resources Canada], a party to the agreement.”

Chief Piétacho also said that the federal government failed to meaningfully consult First Nations during the regional assessment process, particularly about the implications of removing substantial federal oversight on new oil and gas projects.

In its 2019 request for an extension, the Regional Assessment Committee said that, while it was making progress, it believed that “building trust with Indigenous groups” was “not a fast-paced process.”

When asked about those comments by the committee, Piétacho told The Narwhal that government officials lost the trust of First Nations years ago based on Canada’s historical and current treatment of Indigenous communities.

“I know from experience, the decisions are already made and after that they come tell us that they are coming to consult us on a project,” he said.

Previously, Piétacho had noted in a February 2020 letter to the Impact Assessment Agency, that members of the Regional Assessment Committee would often provide dates and topics of meetings “at the last minute, giving us little time to prepare to contribute in a significant manner or even just to simply participate.”

Macdonald, with the Impact Assessment Agency, said the agency prioritizes “building long-term partnerships with Indigenous communities and people. Sustaining these relationships over the long term is vital for the success of assessments.”

She added that the agency’s Indigenous Advisory Committee as well as several programs are geared towards building that relationship and fostering trust. That includes the Indigenous Capacity Support Program which works to increase capacity for Indigenous Peoples to meaningfully participate in assessments.

Citing over 100 workshops and technical meetings and $436,000 in participant funding for Indigenous groups and other stakeholders, Macdonald called the regional assessment process fair, open and inclusive.

She listed literature reviews on the potential effects of exploratory drilling and initial drafts of potential recommendations as examples of information provided to Indigenous people in advance. “Some of these documents were provided nearly two months before their draft versions were released for a 30-day public review period,” she wrote in an emailed response.

Piétacho wrote in his February 2020 letter that the committee’s draft report lacked clarity, was rushed and inadequate, and was based on a vision of promoting offshore oil and gas development instead of promoting the protection of the ocean.

“It is concerning that, as the committee notes, too often the scientific expertise of the federal government was not available to support the assessment,” he said, in the letter, dated Feb. 21, 2020.

Just over a week later, the regional assessment report on oil and gas exploration in Newfoundland’s offshore was submitted to then-environment minister Wilkinson.

In their submission letter to Wilkinson, the committee’s co-chairs emphasized how the tight timeline hindered their work. One challenge this presented, they wrote, was limiting “the opportunities for others to contribute. Another was gaining the support of all the parties who should have been available to facilitate our work resulting in significant, additional effort to access important expertise.”

Nonetheless, four days later, on March 4, 2020, the final report was released to the public. On that same day the Impact Assessment Agency put out a discussion paper on the regulation exempting exploration drilling in Newfoundland and Labrador’s offshore from project-specific assessment.

That April, Piétacho sent another letter to then-environment minister Jonathan Wilkinson, criticizing the proposed regulation. He wrote that it would eliminate the consultation stage with Indigenous people about whether to approve any future exploratory drilling.

The letter also noted that even before the committee’s draft study was released, the government had published a notice predicting that the report would be used to introduce an exemption on federal reviews for exploratory drilling permits.

“Not only is the process hasty and seems to indicate bias for production of hydrocarbons, it fails to really take into account the rights of Indigenous peoples,” Piétacho wrote.

As Piétacho expected, the exemption regulation was enacted on June 4, 2020.

Piétacho told the Narwhal that much is now at stake, for First Nations Rights, but also for everyone else.

“I’m concerned and I’ve taken on this file on behalf of the Innu Nation to defend our principles and dreams,” Piétacho told The Narwhal. “I’m not doing this for myself. I’m doing it for future generations.

With files from Mike De Souza.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...