Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

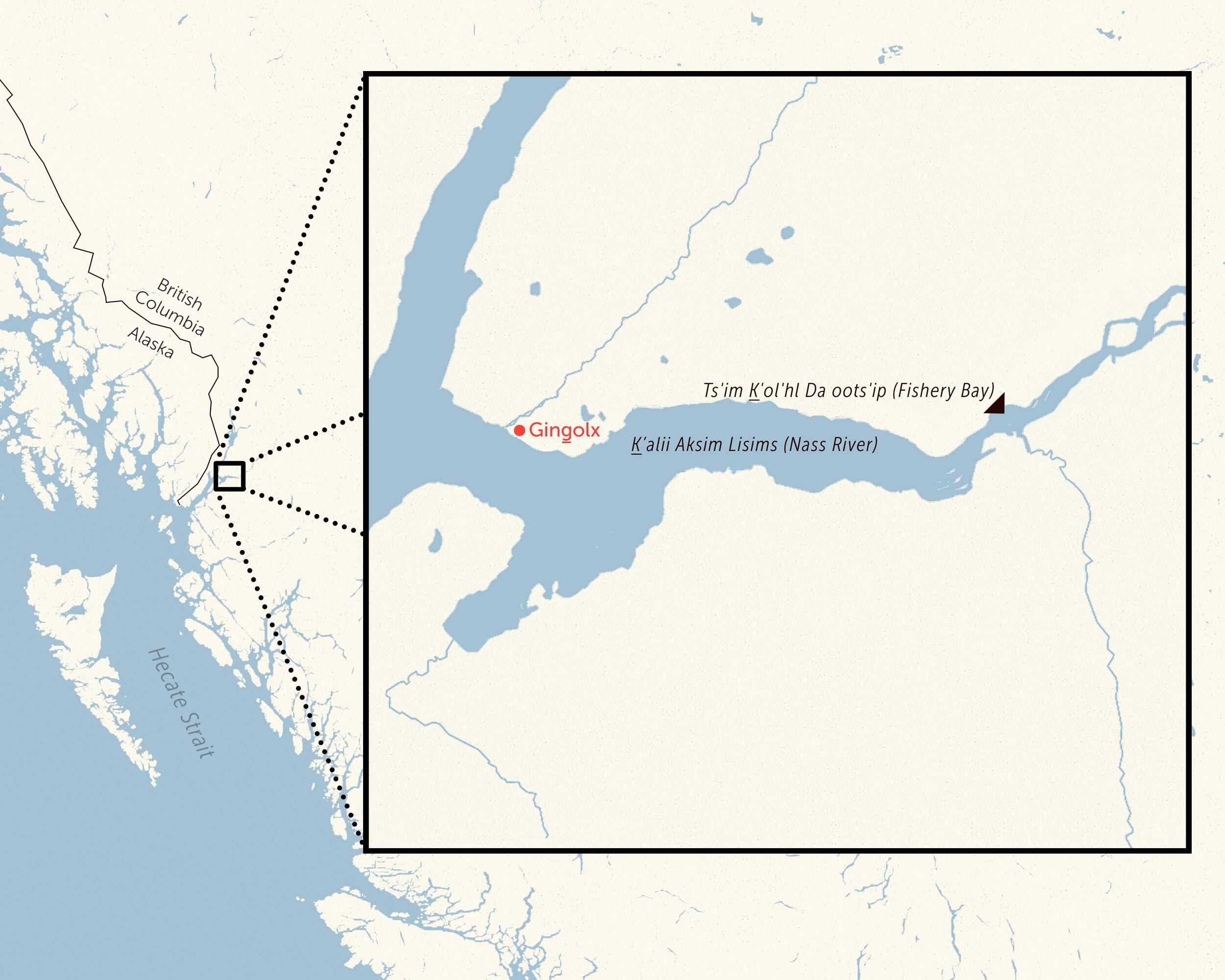

A group of kids from the northwest village of Ging̱olx scatter around a Nisg̱a’a fish camp overlooking Ts’im K’ol’hl Da oots’ip (Fishery Bay), whacking sticks against stumps, munching on fruit bars and climbing anything that looks like it can be climbed. Some of the older kids lean against trees, talking quietly with each other.

It’s cold and damp and the camp is suffused with the smell of fish, forest and sea breeze blowing upriver from Kʼalii Xkʼalaan (Portland Inlet).

The kids are here to learn about — and from — saak, a little oily fish that returns in the early spring to Kʼalii Aksim Lisims, the Nass River. Saak goes by a lot of names: eulachon/oolichan, ooligan, hooligan, candlefish, saviour fish. The Nisg̱a’a have other names for it, too, depending on how it’s processed: digit is smoked, digidim lax-sk’an loots’ is sun-dried and t’ilx is the grease made from rendering the fish.

“Ńit, aam wilaa wilina?” Mansell Griffin asks the group as they’re corralled by Andrea Reid and her graduate students, Kasey Stirling and Kate Mussett. Reid is a Nisg̱a’a Nation citizen and scholar with the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Indigenous Fisheries. She brought these 12 kids here as part of a three-day oolichan science camp run in partnership with the Ging̱olx Village Government.

She softly prompts the kids, asking them what Griffin said. They translate in a quiet chorus: “‘Hi, how are you?’”

Griffin works for the Nisg̱a’a Nation as director of lands and resources, but today he’s here as a member of the fish camp to give the group a tour. He explains a bit about the process of catching and processing saak and notes the Nisg̱a’a names for nets and tools, like ganee’e, the rack used to dry the fish, which he says sounds just like the noise a seagull makes when it eats saak. He gets some giggles as he mimics holding a fish above his mouth and calling, “ganee’e, ganee’e, ganee’e, ganee’e.”

He asks if anybody knows why the oolichan run the river in March.

“To save us?” one kid answers.

“Yeah, but they were tricked,” Griffin says. “They didn’t know they were coming to save us ’til they got here.”

The trickster, he explains, was Txeemsim, grandson of K’am Ligii Hahlhaahl, the Chief of the Heavens.

“Txeemsim saw that everybody was hungry. All of our salmon was done. We were running out of our winter stores. We didn’t have freezers and refrigerators back then — we dried all of our food. And people were running out, people were starving. It was a really cold winter, it was hard to hunt and we were running out of dried fish.”

“So Txeemsim decided he was going to do something about it. He went to their village and he made his canoe go under the water. When he got there, it was just like this. He got under the water and suddenly he was in a place where he could put his canoe on the beach. And there was the village of the oolichan people. And he tricked them.”

“He said, ‘You guys are late! All the other oolichan villages already left for the Nass, you guys are late!’ He had smeared herring eggs on the inside of his boat and he said: ‘Look, I’ve been catching them already, look at all the eggs inside my canoe.’ ”

“So the whole village all jumped into the water and made themselves turn into oolichans and started swimming up the river. When they got here, they saw everyone was starving. They were so happy to feed us.”

“The ones that didn’t get caught, their bodies were washing back down the river and they saw the spring salmon starting to come up the river and the oolichans laughed and said: ‘You guys are too late, we already saved all the Nisg̱a’a!’ And the spring salmon said: ‘Who are you going to save? My head is bigger than 10 of you.’ And they have that argument every year still.”

Oolichan is a prized commodity that plays a vital role in the lives of the Nisg̱a’a and other Indigenous communities along the Pacific coast. As Griffin points out, the fish arrive at a time of year when other staples are exhausted and wildlife is scarce. The oolichan are also followed by other important food sources like sea lions, which are harvested by Nisg̱a’a hunters. The return of oolichan to K’alii Aksim Lisims also lines up with Hobiyee, the Nisg̱a’a new year.

The northwest can be a harsh place in late winter and early spring, with violent storms battering the coast, ice still covering the rivers and lakes and snowpack in the mountains impeding travel. When the oolichan come, it’s an opportunity to replenish supplies. Because the little fish is packed with vitamins and fatty acids, it helps stave off the impacts of months of dark, cold and wet conditions.

A vast trade network known colloquially as grease trails connects coastal First Nations with the interior. They’re called grease trails because communities on the coast capitalize on the high oil content of the fish, rendering part of their annual catch into oolichan grease and trade or gift it to nations in the interior.

Some grease trails that were etched onto the landscape over thousands of years are now highways, built over the paths first charted by First Nations travelling to and from the coast to trade.

Like so many species, the little oily fish is suffering from the likes of climate change, habitat degradation and other impacts. The Fraser River and central coast populations, for example, are listed as endangered on Canada’s species at risk registry.

“There is convincing evidence of a sharp downward trend in most eulachon runs during the last 30 to 40 years,” the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada notes in its general assessment of the species. “Eulachon spawning runs in several rivers are virtually extirpated; most others are severely depleted.”

The Nass River population remains relatively stable (it’s listed as a species of “special concern”) but because so little is known about the species as a whole, it’s uncertain whether that stability will hold over time.

“If population trends in rivers are considered over a longer term (e.g., a century or more) it is clear that most eulachon spawning runs in traditional areas are now only remnants (less than 10 per cent) of their past abundances,” the federal committee notes.

This collapse is consistent with global trends in biodiversity loss and an urgent signal to ensure future generations have a connection with the species and the ecosystems which support its survival.

The number of kids in the group is constantly in flux over the course of the three days. At times their level of engagement ebbs like the tides many have grown up with. It’s hard to read the kids at times and the ways they show their interest doesn’t fit with a settler construct of what a science camp should look like.

“I’ve wanted to move away from high structure because I think it’s artificial here,” Reid says. “Why not just create a support system and show up and continue to show up twice every year so they can count on us?”

Reid has run two camps every year since 2016 — one in spring and another in the summer — with a variety of focuses, including salmon, water, Nisg̱a’a adawaak (oral histories) and more. This year is the first oolichan camp.

“We’ve done everything from using underwater drones, to searching for petroglyphs, to testing water quality to running radio telemetry-based scavenger hunts in the community,” she says.

In 2021, she partnered with the Ărramăt Project, an international Indigenous team “working together for research and action in support of the health and well-being of the environment and people,” to secure funding. That funding, she says, will help her to expand the camps to include youth from other Nisg̱a’a communities and to enable exchanges with other Indigenous communities to learn more about salmon in different contexts.

The structure of the camps is loose, flexible and spontaneous. As she points out, this better reflects the kids’ personal lives. It’s less about classroom-style science and more about being present.

Her way of leaning into sharing space in this way is also extended to me. On most assignments, photographer Marty Clemens and I are present in an observational way. Clemens is the proverbial “fly on the wall” behind his camera and while I ask questions, listen and engage, I’m there to document not participate.

Here, we are very much part of everything that’s happening. We play games with the kids, we eat snacks with them. I find myself talking about hunting and fishing with Antwone, one of the teenagers in the group, and I quickly become the point-person to fix Rocko’s slingshot. Clemens plays pool on a mini table and talks basketball with Caleb, who proudly sports a Toronto Raptors jersey, hoodie and hat. We keep an eye out for moments that might need a little adult intervention and generally interact with everyone in an intimate and personal way.

This isn’t about sitting down at a desk and learning from a book — and that’s intentional.

“We’re positioning it towards learning from the fish and those who are interacting with the fish,” Reid says.

Stirling, who is Nlaka’pamux, Mi’kmaq and Acadienne and grew up on T’exelcemc Nation territory, notes these kids already inhabit a world of science — it’s just not necessarily labelled as such. Their families hunt and fish and, in paying attention to seasonal changes and landscape-level details, they’re acutely aware of the fundamental connections within ecosystems, she explains.

“You can’t not think about how everything is affected by any other factor,” she says. “How could you ever not think about that when you are living on the land so close? I think a lot of kids are disconnected from it in cities … but that’s not something you can get away from living here.”

Reid agrees and says showing kids how much they already know — and emphasizing that the way in which they understand the world around them is healthy — empowers youth to become more curious and explore science in a deeper way.

“A big part of it was just recognizing that we could do it in a way that can be youth driven and curiosity driven and departing from structure and allowing us to just spend time with these kids and just be in the community as they are.”

Stirling says connecting with kids in communities like Ging̱olx needs to be responsive and fluid for it to resonate and have any chance of making an impact.

“The best for one kid isn’t the best for another kid,” she says. “Everything is context based, which makes the work harder, but it’s the way it’s got to be.”

Reid adds the camps provide access to parts of the territory that youth don’t often get to experience, noting that some of these kids have never been to Ts’im K’ol’hl Da oots’ip despite it only being about a 15-minute drive from the village.

“There are many people in this community that don’t get to see these things firsthand,” she says. “And yes, they’re kids and they get there and they’re like, ‘we want snacks’ and ‘we’re ready to go’ and all of these things, but I think it does impact them and I think it sticks with them in a way that is meaningful.”

Inside the wilp jam (cooking house) Byron Stevens laboriously stirs the steaming contents of a large rectangular vat. He’s making t’ilx — oolichan grease. At the bottom of the soupy mixture are the fish, pre-fermented for a week or so before being transferred into the vat, where they are boiled and simmered in water. How long the saak are left to rot depends on the volume of the catch and the type of grease they want to make. The longer the fish are left, the darker the grease, which ranges from white to golden honey to dark amber. Everyone has a preference.

Stevens has been stirring since 5 a.m. — it can take more than 12 hours to process each batch of t’ilx.

Griffin leads the group inside. Some kids dramatically pull their shirts up to cover their noses and make giggly comments about the smell. A couple of others admit they like it and seem surprised at their own reaction. It’s fishy and strong, but not sour or overwhelming. Griffin says after a couple of days you don’t notice it anymore, though it tends to cling to clothing and skin.

The process might be labour intensive but it’s relatively straightforward: cook the fermented fish in water, keeping things moving until the fish break down. After a period of simmering, the oil starts to separate and rise to the top of the mixture. When partially cooled, the grease can then be extracted from the top of the vat and the remaining water and fish parts drained into a creek running down beside the camp into the river.

With his son watching, Byron Stevens stirs a vat while rendering oolichan grease at a camp on Ts’im K’ol’hl Da oots’ip. It can take more than 12 hours to process one batch.

When this batch of fat is finally rendered, Stevens says he’ll try to sneak in a couple of hours of sleep before the tides change and he’s back out on the boat casting and hauling in nets. They fish with the tides, even if it’s in the middle of the night. His son, Byron Jr., opts to stay with his dad when the group leaves.

After regrouping at the village longhouse, we all walk over to an Elder’s house for a talk about why oolichan is so important.

Sim’oogit Sigadim nak’ Lavinia Clayton is short and her bobbed gray hair frames a friendly smile as she gently greets everyone on her porch.

“We’re very, very fortunate that we’re able to get all our food right here, right here and up the Nass,” she says as a raven softly calls from the waterfront. “Oolichan is very, very special food for our people. The grease is so good for our health. It’s a lifesaver: you get poisoned and you drink it and it saves your life.”

As she speaks, the kids settle into a busy kind of quiet. Most are fidgeting and restless, but it’s obvious they’re listening. Caleb shares his chocolaty snack with me.

She talks about her childhood, processing salted oolichan for drying, her fingers cracked and sore from tying threads through their heads. Her mom would wrap her fingers so she could keep working.

“They always tell us, ‘If you’re lazy, you get hungry.’ ”

“I really thank the good Creator for all these things that comes our way, especially our seafood out here. We get a lot of crabs, halibut, prawns, species of salmon.”

Her eyes twinkle as she passes on a key piece of advice to the group.

“Don’t be ajiks. In other words, don’t be fussy with what you eat.”

She brings out a steaming pot. Holding it with a tea towel, she hands out oolichans in tinfoil. They’re smoky and warm and delicious. Some kids don’t like to eat the head and tail but they all try it.

The raven calls again and Stirling nudges a couple of kids.

“Did you hear? He was trying to trick us,” she says smiling.

Later, after the kids head to their homes for the night and Reid, Stirling and Mussett tidy up and prepare for the next day, Clemens and I wander the village looking for something to eat. It’s off-season and sleepy.

Herbert Benson is busy brining plastic-totes-full of oolichan in his front yard. He wrangles the fish from one tote to the next with a homemade tool that looks a bit like an oversized lacrosse stick. Behind him, drawn onto the window of the house is an orca and the words, “Wilp’s Daxaan.”

“That’s where we are,” he explains, gesturing to the village.

A radio on the porch blasts the news as he moves fish from one tote to another, rinsing them several times with fresh water in preparation for the next stage of processing. He’s preparing the fish for an Elder and says they’ll be hung in a smokehouse to dry because it’s been such a cold and wet spring.

“You see the red eye, with the black pupil?” he says, pointing to the fish. “When they turn white in the brine, that’s when they’re ready to come out.”

He says the runs this year were smaller than previous years and that he’s concerned about climate change. The runs are coming earlier, he explains. How does he know? The seagulls. When they congregate on the river and flock to the estuary, the runs are starting, he says.

If the runs come too early, Nisg̱a’a fishers can’t safely get out onto the river to harvest because of ice jams and late-winter weather.

“This year, too much storm. Too much stormy weather.”

Benson is preparing the oolichan for Bonnie Stanley, owner and proprietor of U See Food U Eat It. It’s the only place in the village to get a meal and his across-the-street neighbour.

The restaurant is closed when we arrive but we’re told by another community member to knock on the door of the house beside it.

Stanley greets us and kindly agrees to open up the restaurant. She prepares salmon sandwiches and halibut chowder and within a few minutes, she opens up about the death of her son. He died of a fentanyl overdose in Surrey almost a year ago, she says. For that year of mourning, she’s been wearing black every day and is only now starting to talk about him again.

She says she’s been preparing for a celebration of life gathering and plans to take a seafood feast down to the Lower Mainland. Normally she’d process her own oolichan, but busy with preparations, which includes finishing her button vest, she asked Benson to catch and process saak for the feast.

While her grief is written on her face and carried in the way she speaks of her son, she’s clearly proud to honour his memory with food harvested and processed on Nisg̱a’a territory.

She laughs as she tells us how her fingers ache from working on her button vest. I can’t help but connect it in my mind to a young Lavinia stringing up oolichan to be dried in the spring sun.

On our last day, the kids learn about water quality, testing samples for the likes of salinity, dissolved oxygen, conductivity and pH levels. In the longhouse, they’re given a crash course and later we head to a nearby creek behind the village to test their newfound skills in the field.

As we walk, 11-year-old Edward tells Clemens the story of Raven bringing the light. Maddy tells me about her dog and how she just moved into the village so her dog doesn’t get to play with its old friends anymore. A couple of rez dogs join us for a while before peeling off to sniff at something more interesting. At the creek, Rocko learns to skip stones for the first time.

“Where I come from is on the other side of the country and a whole different ocean,” Mussett tells everyone, standing on the shore of the creek. She’s wearing bright yellow gumboots and has a clear rapport with most of the kids. “But every time I come to water like this or the inlet or I feel the rain, I know that water is following me wherever I go — it’s the same water in different forms. And it’s our responsibility to protect it.”

A couple of the kids start howling like wolves.

It starts to rain and Reid huddles with the group under the cover of the trees along the shoreline. As the kids measure a water sample for dissolved oxygen levels, she tells them how some fish can survive with almost no oxygen and talks about how gills work.

“They’re taking oxygen from the water as it moves over their gills,” she explains. “Gills are like roots — so there’s one piece of gill and then it spreads and spreads and spreads into little capillaries.”

I ask who would want gills if they could have them and only a couple of kids immediately say yes.

“What if you could have gills and lungs?” Reid asks with a grin. “That’s the future.”

To the youth, families and community members of Ging̱olx, and all who welcomed us into the community and shared their stories with us, t’ooyaksiỳ n̓isim̓ (thank you).