‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Some residents of North Bay, Ont., are expressing doubts about Mayor Peter Chirico’s defense of a new plastics factory set to open in the city.

Jason Harris, an Ojibwe filmmaker who has lived in the Nipissing region his whole life, said he’s still worried about polytetrafluoroethylene, also known as PTFE. Part of a group of chemicals known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PTFE is set to be used at a factory run by Industrial Plastics Canada, as The Narwhal reported on July 6.

“The reaction from our community has been overwhelming and unanimous: we do not want PFAS in North Bay and area. Conversely, the municipal government has defended Industrial Plastics Canada’s actions and intentions,” Harris said to The Narwhal in an email.

Both Industrial Plastics Canada and the mayor have said the plant will have no impacts on the environment or public health. Chirico’s July 11 statement said, in part, that the factory “will not manufacture raw plastics on site, and its operations will not have impact on local watercourses. The facility will not discharge to land, or water.”

Previously, the company told The Narwhal that polytetrafluoroethylene does not present the same risks as other PFAS and are “considered safe, non-bioaccumulative and non-toxic.” After the story was published, the North Bay Nugget published an opinion piece by company president Andrea Arlati saying that “no water from the manufacturing process is discharged into any lakes, streams or other bodies of water” and “no material waste is produced.”

Some people in the region say they aren’t convinced.

Nearly 1,400 members have joined a Facebook group Harris started called “Stop Industrial Plastics Canada” in order, he said, “to educate and engage the local community and beyond.”

And community organizer Michael Taylor helped set up a town hall at the local Ontario Public Service Employees Union building scheduled for July 20. City officials have been invited.

Chirico’s statement also said that he and his office “understand that recent news and social media posts have raised concerns and misconceptions about Industrial Plastics Canada and its operations in North Bay.” Chirico did not specify which news or social media posts he was referring to. Nor did he identify any specific elements of any statement that he considered to contain misconceptions.

Saying the city wanted to “clarify some of the information circulating,” the statement said that the company’s “Air standards will be required to comply with Ontario environmental legislation and regulations like all manufacturers in the city of North Bay and within the province of Ontario.”

“We will continue to work with [Industrial Plastics Canada] as the company completes construction and begins operations,” Chirico’s statement concluded.

Chirico did not respond to questions from The Narwhal asking how the city had previously worked with the company or provide details on how it would work with the company moving forward.

Marco Nocera, quality and customer care manager for Industrial Plastics Canada’s parent company, Guarniflon, previously told The Narwhal “We stay up-to-date on all developments through our corporate departments and initiatives that lead industry research and liaise with government to establish or update safety and environmental standards.”

Harris said his online group has discussed concerns for their health and the health of Lake Nipissing and other local waterways, which are already contaminated with PFAS from decades of National Defence firefighting training that began in the 1970s.

“I’m not sure that this company or even our city can fully guarantee that there’s going to be safe handling of these materials,” Taylor said. “You can build a facility that is completely hermeneutic, completely separate and it’s got all these precautions. But that chemical compound, those pellets still have to be transported across from wherever they’re coming to here.”

When The Narwhal toured the Industrial Plastics Canada factory in June, Arlati opened a box marked “from India” which he told this reporter contained PTFE, in what appeared to be chunky powder form. The Narwhal did not handle these materials.

PFAS is an umbrella term for thousands of chemicals which, if not disposed of properly, can contaminate air, water and soil for about 1,000 years, often harming human and wildlife health. PTFE is part of a subgroup of PFAS known as fluoropolymers, which are not included among the PFAS that Canada currently regulates. Although the federal government is currently studying the chemicals and deciding how to approach PFAS as a class, the lack of existing regulations means that the Industrial Plastics factory is not required to have an environmental assessment before opening.

Industrial Plastics and others in the industry say fluoropolymers aren’t as dangerous as other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Previously, the company shared a YouTube video posted by an India-based chemical company, Gujarat Fluorochemicals, making that argument, as well as a March 2018 review of scientific information on fluoropolymers that states they are “polymers of low concern” and should be considered separately from other PFAS by regulators.

But local and global researchers and advocates disagree. As The Narwhal previously reported, Fe de Leon, a researcher with the Canadian Environmental Law Association, cautions against viewing fluoropolymers as PFAS-free. The European Union is discussing banning all PFAS as a class, including fluoropolymers like PTFE.

Curtis Avery is environment manager at Nipissing First Nation, whose job is to monitor his nation’s lands and waters. He told The Narwhal he has concerns about the plant because he worries about the effect of existing and potential future pollution on his community, many of whom live off of the land.

“In the future, I do plan on doing some sort of contaminant studies and it would be interesting to see if these forever chemicals are in meats that we’re getting from our staple food items in our forests,” Avery said in an interview.

The city did not respond to a number of The Narwhal’s questions about the factory and company, including how North Bay has worked with Industrial Plastics Canada previously, which misconceptions the mayor was referring to, how the city reviewed the company’s building permit applications and how North Bay will ensure its waste will not become a problem for local landfills.

Industrial Plastics Canada is part of a conglomerate headquartered in Italy called Guarniflon, owned by Mazza Holding, whose website proudly states it has processed 10,000 tons of raw material polytetrafluoroethylene throughout its global operations. It has a presence across Europe as well as in India and China, calling itself one of the “largest worldwide manufacturers of PTFE products.”

Ontario’s environment and economic development ministries did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions about inspections, air quality monitoring and the lack of a notice about the Industrial Plastics Canada factory on the province’s environmental registry. The government is required to post information about certain business permits under the Environmental Bill of Rights.

On July 19, CBC reported that the environment ministry had visited the Industrial Plastics Canada site on July 11 and determined it was not yet operational. “We made the company aware of their requirements under the Environmental Protection Act,” the environment ministry said to CBC. “It is possible that the company will require an environmental compliance approval for air emissions before entering production.”

CBC also quoted an Industrial Plastics Canada production manager who said the plant would use ovens during a heating process to convert the powder into a solid piece. The CBC also reported the manager said the company would need a provincial permit from the ministry prior to using the ovens and that staff would “wear masks as a precaution when loading the PTFE powder into the moulds.”

The provincial ministry did not respond to requests for comment from The Narwhal on June 13, June 30, July 17 and July 19. A lawyer representing Industrial Plastics Canada did not respond to a July 19 request from The Narwhal, asking whether they could confirm the ministry’s visit on July 11 and the CBC’s reporting.

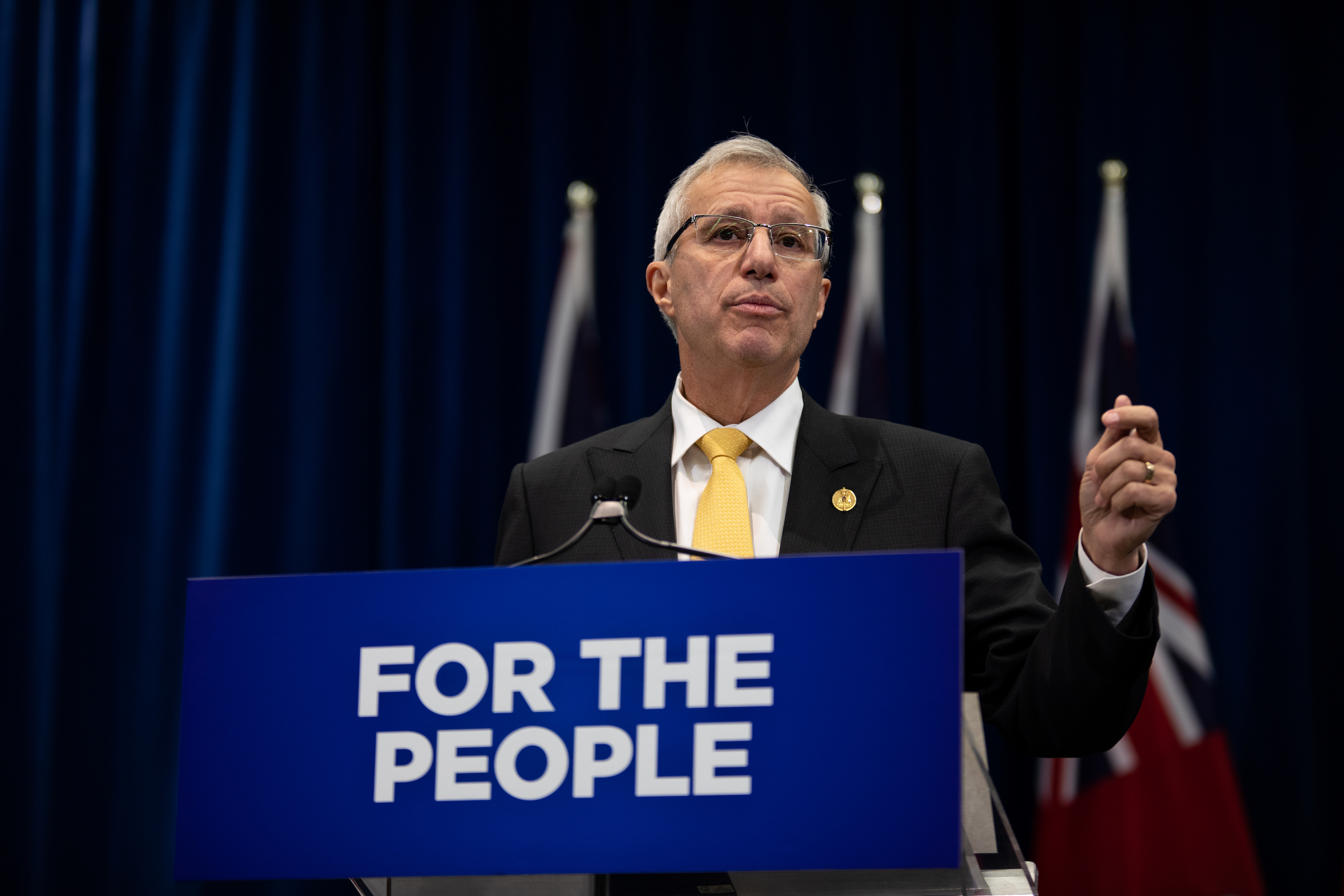

Local MPP Victor Fedeli, Minister of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade, previously promoted the new factory during a visit in January, when he tweeted a photo of himself at the site with general manager Steve Fowler.

With Steve Fowler, GM of IPC in North Bay (div. of Guarniflon).

The company manufactures semi-finished PTFE parts for auto, aerospace, food & beverage, bridge construction and virtually every valve or tap produced.

North Bay will soon see 30 employees making billets and film. pic.twitter.com/0mBuUyA3cW

— Victor Fedeli (@VictorFedeli) January 19, 2023

“The company manufactures semi-finished PTFE parts for auto, aerospace, food and beverage, bridge construction and virtually every valve or tap produced. North Bay will soon see 30 employees making billets and film,” Fedeli wrote.

Fowler personally thanked the minister and North Bay Economic Development after the January visit, writing on his LinkedIn page “they have been extremely helpful, professional, and the guidance has been bar none. There are so many great reasons to start up a business in North Bay. For us, there was no other choice.”

Fedeli’s office did not respond to emails from The Narwhal asking how the government will ensure Industrial Plastics Canada poses no risks to the local environment or human health. The minister also did not respond to a question asking how he decided to support the project.

The minister’s comments were similar to what Fowler told local media last summer when he said “we are going to be making a product here called PTFE.” Industrial Plastics Canada identifies itself on its company logo with the slogan “The Canadian PTFE Manufacturer.”

Previously, Industrial Plastics Canada has told The Narwhal that it will only be using polytetrafluoroethylene here, not making it. “PTFE comes in the sugar form. And we just shape it in a solid form,” Arlati said. “It’s like if you go to Walmart, and you buy flour to make bread. You don’t make the flour. You make the bread.” In the North Bay Nugget, Arlati again emphasized that Industrial Plastics Canada doesn’t “manufacture” PFAS.

Industrial Plastics Canada did not answer questions about Fedeli’s statement, the slogan or the sign and said, through Ontario lawyer Nelson Amaral, that any further communication from The Narwhal would be “deemed harassment.” Questions sent to the company through Amaral were unanswered.

In an email, Amaral said that the company’s safety record is “spotless.” He also said “PTFE and PFA are not one [and] the same.” Amaral also sent a chart that he said shows PTFE is “separate but related” to “PFA.” It was unclear whether he was referring to the umbrella category of PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalykl substances, or the specific substance listed on the chart as “PFA,” with the full name “perfluoroalkoxyl polymer.”

The Narwhal has not reported that the chemical known as PFA is present in the Industrial Plastics Canada factory. As the chart sent by Amaral shows and The Narwhal has reported, the chemical being used at the factory, PTFE, is included among the broad class of chemicals known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalykl substances. Amaral did not provide a response to questions sent by email, asking for clarification.

Amaral also included the same YouTube video previously sent to The Narwhal: while it states fluoropolymers are safe, the video does note the need to dispose of them via extremely high heat, “secure landfills” or regulated waste collection, saying that the industry is working on suitable labelling for “proper collection and disposal” of “certain household applications like non-stick frying pans.”

Previously, customer care manager Nocera told The Narwhal that much of the danger posed by fluoropolymers was due to “degradation,” or how products break down over an “entire life cycle”and that this was an issue for government. “Disposal of such items is outside of our control and falls under the jurisdiction of the governments of Canada, specifically the Ministry of Environment,” he wrote in an email.

Taylor, who is organizing the town hall, said his hope for the meeting is to gather knowledgeable people who can shed light on the situation. “I would like to see some environmentalists, I would like to see a whole group of people get together and discuss this because this is not just a North Bay thing,” Taylor said. “They are bringing this product from somewhere … and if there’s an accident or something happens in North Bay and if they’re not careful about how they handle these materials, where they’re located is between three primary lakes that are all part of a watershed.”

Even if PFAS are regulated as a class in Canada, ensuring the chemicals stop entering water, soil and air will require all levels of government onboard. While Health Canada is figuring out how to approach the ever-evolving science and set safe drinking water limits accordingly, it currently only regulates a fraction of existing PFAS, three compounds of what De Leon’s office estimates is a group of 12,000 chemicals. Statistics Canada reports almost everyone in Canada already has PFAS in their bodies, including in remote regions such as the Arctic and subarctic.

As part of its current process, Health Canada published a “draft objective” level of 30 nanograms per litre in February. Once the federal department finalizes and publishes its guidance, provinces will have to decide their own guidance and regulations. Then, municipalities will be left to do the actual monitoring, with the federal government responsible for water quality on First Nations.

Past National Defence contamination has likely affected hundreds of sites across Canada. According to the city, North Bay’s drinking water contained 60 nanograms of PFAS per litre last spring, which is when a study about how to tackle existing PFAS contamination was supposed to come out. Now, some residents are meeting to discuss the imminent introduction of a whole new set of chemicals at a factory in the community — while they wait for a solution for the old ones.

— With files from Denise Balkissoon

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...