Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

In southern and central B.C., caribou are struggling. Some herds have been wiped off the map, their habitat steadily eroded by logging and mining, criss-crossed by roads, or otherwise intruded upon by people.

Other herds are just hanging on, their numbers dwindling, as Indigenous communities and scientists race to prevent any further losses.

In northern B.C., caribou populations are comparatively in better shape, but a new assessment from Wildlife Conservation Society Canada shows at least two herds are also declining as industry, wildfire and other pressures slowly eat away at their habitat.

But in the north, there are still large stretches of land unencumbered by industry. That means there’s still time to prevent caribou populations from reaching the crisis levels of their neighbours to the south.

“There aren’t many places left where you can say that we still have a really good chance to do good stuff, to take proactive action,” Justina Ray, a co-author of the assessment, and president and senior scientist at the conservation society, told The Narwhal.

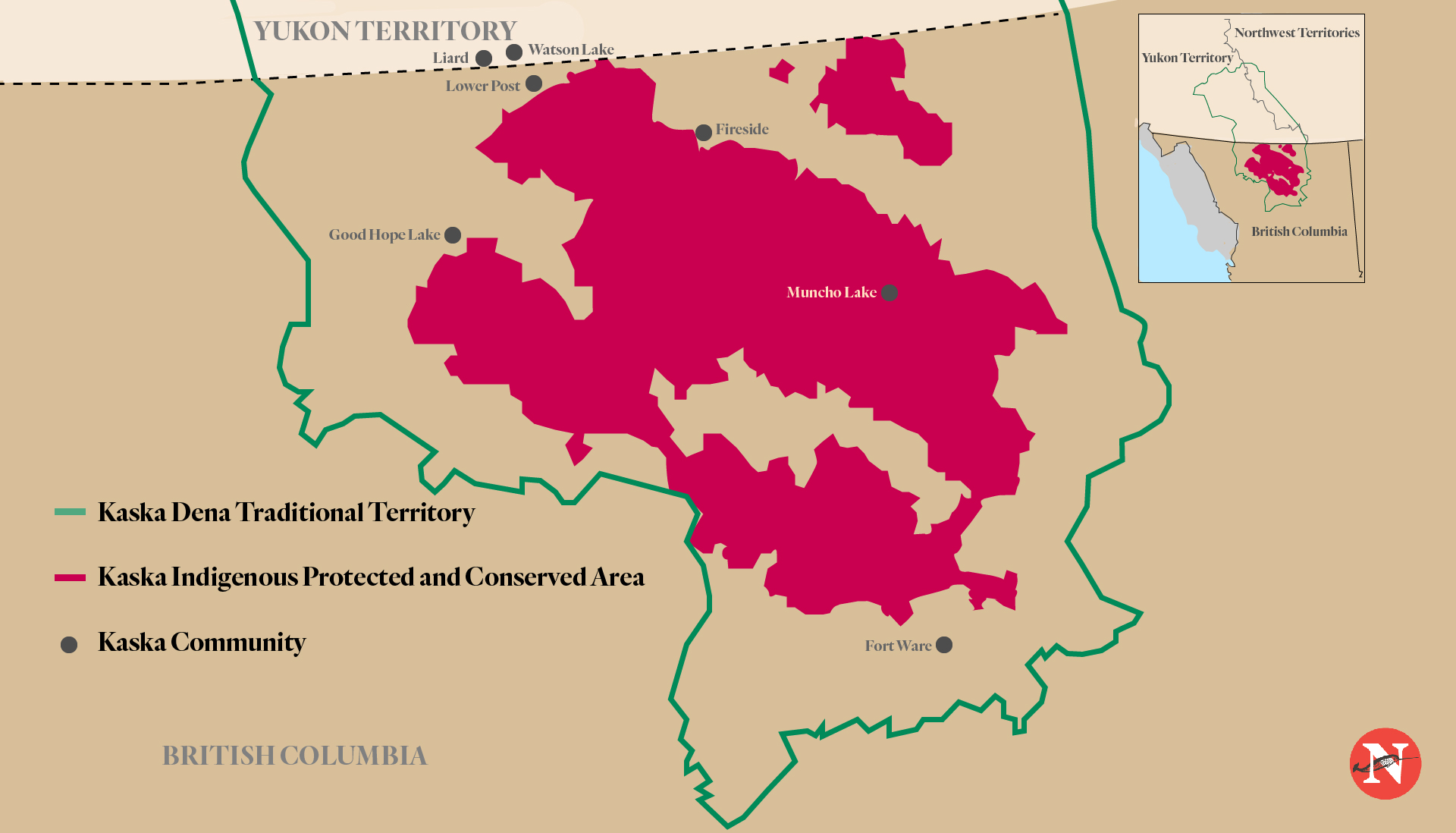

For caribou, northern B.C. is one of those places — and the Kaska Dena have proposed a large Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area, or IPCA, that would help protect vital northern mountain caribou habitat.

“Our Elders have been saying for decades that our caribou are declining,” Gillian Staveley, the director of culture and land stewardship at the Dena Kayeh Institute said in an interview.

Just this week an Elder told her that “at one time, there were so many caribou here, that when they were near them, it felt like thunder, like the whole ground would shake,” she said.

Today, northern mountain caribou are “not thriving in the north, it’s just when you look at it in comparison to herds that are basically on life support, they’re in triage mode down in southern B.C.,” said Staveley, whose given Kaska name is Mésdzį̄h.

Caribou are highly sensitive to habitat disturbance. In some cases, they are pushed out by resource projects or wildfires that destroy habitat. Even more temporary disturbances, such as snowmobiles or resource exploration, can cause these iconic ungulates stress, forcing them to flee, said Chris Johnson, a professor of landscape conservation and management at the University of Northern British Columbia, who has spent years studying northern mountain caribou.

Other impacts are less direct. The plants that tend to grow back first after wildfires or resource extraction are more inviting to moose and deer than caribou. As these species move into caribou territory, they’re followed by predators, like bears and wolves, Johnson said. While deer and moose populations may be able to withstand an increase in predation, the same can’t be said for caribou.

At the same time, roads or snowmobile tracks in the winter can make it easier for predators to reach caribou in otherwise remote areas in the alpine, Johnson explained.

According to the new assessment, protecting caribou from future declines will require getting better at monitoring their populations and the impacts of human activity — and ultimately prioritizing conservation of the habitat they rely on.

Northern mountain caribou are found in north-central and north-western B.C. and rely on large stretches of intact habitat. They spend time at lower elevations during the early part of the winter, feeding on lichens that grow on the ground, before moving into windswept alpine regions. There, they forage through shallow snow for lichen and other plants, said Johnson.

Southern mountain caribou, meanwhile, tend to spend their winters in alpine regions with much deeper snow, where they feed on lichen that grow on trees, he said.

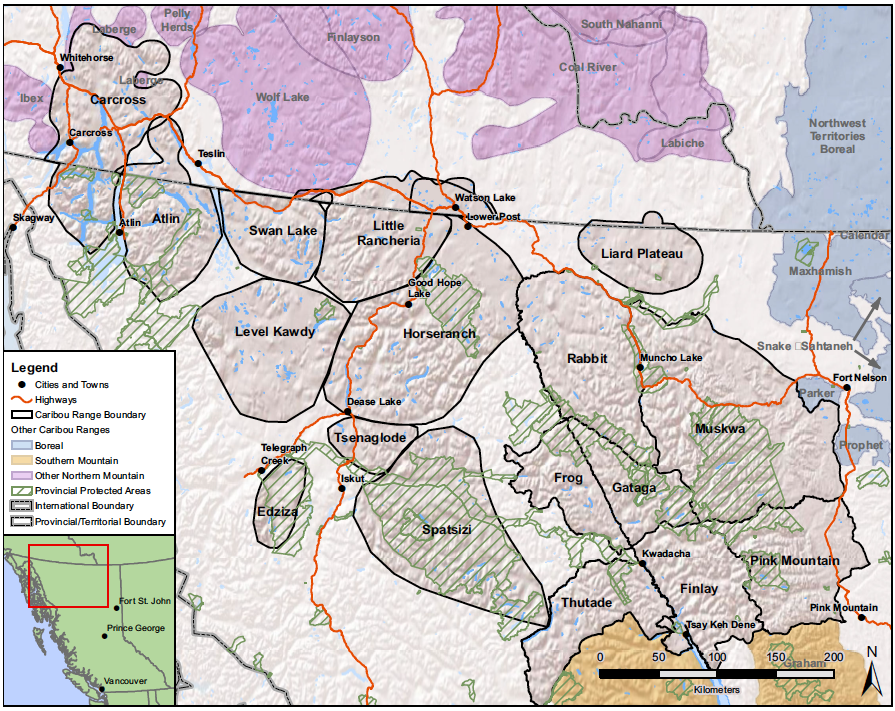

While caribou habitat in northern B.C. is relatively undisturbed compared to the ranges of southern herds, the new assessment of 17 northern mountain caribou populations shows there’s reason to be concerned.

All 17 populations have special concern status under the federal Species at Risk Act, which means they are considered at risk of becoming threatened or endangered.

The assessment focuses on habitat disturbance and population trends in northern B.C. It’s a summarization of available technical information, garnered through interviews with biologists, government data on populations and ranges and relevant scientific studies.

The authors wrote that “a much broader understanding of caribou in northern British Columbia would be gained by the addition of Indigenous knowledge,” and note that all First Nations with territory overlapping the caribou ranges in question need to be consulted on any conservation plans including “on how Indigenous-led conservation efforts could improve future conditions for northern mountain caribou in northern B.C.”

Across all ranges, about 15 per cent of northern caribou habitat has been disturbed, the assessment found.

A 2020 analysis by the environmental organization Wilderness Committee found that habitat disturbance levels ranged from 10 to 76 per cent for 17 southern mountain caribou local population units. Ten population units had ranges that were more than 30 per cent disturbed.

The Wildlife Conservation Society Canada report researchers only had enough information to determine long-term population trends for four of the 17 northern herds. They found populations are increasing in both the Atlin and Carcross ranges, which extend into the Yukon. Over the last three decades, licensed hunting has been eliminated and First Nations have voluntarily stopped caribou hunting in the Yukon and efforts to keep wildfire in check seems to have contributed to the increased numbers, the report said.

The three easternmost ranges (Pink Mountain, Muskwa and Liard Plateau) had the highest level of habitat disturbance, with 21 to 35 per cent of their habitat affected. Information was lacking for the Muskwa herd, but both the Liard Plateau and Pink Mountain herds are decreasing. The Liard Plateau habitat was among the worst impacted by fire. And, both the Liard Plateau and Pink Mountain herds’ ranges overlap with the western sedimentary basin in northeast B.C., where oil and gas extraction activities are concentrated, the report noted.

Across all ranges, human impact was commonly seen in the form of roads, trails and industrial activity, such as seismic lines, which are long, narrow strips of cleared land used during oil and gas exploration. Companies send shockwaves down these lines to identify potential gas reservoirs.

Between mineral and coal leases, forestry, expected growth in natural gas production and climate change upping the risk of wildfires and insect outbreaks, pressure on caribou habitat in northern B.C. is poised to increase, according to the report.

“You can imagine, because it’s unfolded so many other times in northern Canada and elsewhere, that piece by piece, project by project, cumulative disturbance can nibble away at these ranges,” co-author Ray, said.

Though it’s not easy to predict exactly where new resource extraction may happen, “what is clear is that there isn’t an overall strategy for managing that cumulative disturbance over this larger area,” she said.

For Johnson, one of the key take-aways is that “some of these ranges are relatively intact. Let’s work to keep them that way.”

“We know what happens when we allow lots of disturbance in these ranges — caribou populations decline and they literally disappear in front of our eyes,” he said.

The Kaska Dena have proposed a large Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in northern B.C.

Called Dene K’éh Kusān, which means “always will be there,” it would protect 40,000 square kilometres of core Kaska Dena territory.

The proposal would help protect a significant portion of seven northern mountain caribou ranges, and in some cases the whole range, from resource extraction or other major disturbances.

For Kaska Dena, protecting Dene K’éh Kusān is “about resurgence,” Staveley said. “It’s about really digging deep into who we are, and making sure that the land is safeguarded so that who we are in our culture is safeguarded in the process, because if we don’t do that now, future generations really run the risk of being disconnected from their land and who they are as people.”

Caribou is a key traditional food for Kaska Dena, who use all aspects of the animal, from the hide and the meat to the organs, Staveley said.

The large size of Dene K’éh Kusān will allow caribou to move easily between their winter and summer habitat as well as their rutting and calving areas, she explained.

“We really believe that IPCAs can help us because Indigenous knowledge is central to the types of decisions that can be made on the land and can be made for our caribou,” Staveley said.

“That traditional knowledge and that wisdom that comes from our communities is necessary,” she said.

Stavely said the Kaska Dena want to see the Dene K’éh Kusān IPCA established under existing B.C. legislation as a conservancy, a measure she said could make it easier for the B.C. government to come to the table.

“It’s through that that we really think that we’re going to be able to bring together the different knowledges that can help steward and manage this land using Crown law and using Kaska law,” she said.

In November 2019, the province passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which requires it to bring all provincial laws in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

To Staveley, IPCAs like Dene K’éh Kusān “are the most practical application” of that new legislation.

“Indigenous-led stewardship and conservation is reconciliation,” she said. It’s also good for the economy and communities.

“It’s part of that healing journey that we’re all on together.”

Establishing the Dene K’éh Kusān Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area would be an important step for caribou, Johnson said.

Protecting northern populations from the stressors seen in the south will require careful management of land use outside protected areas as well, he said.

“We’ve seen caribou populations decline in protected areas in southern and central B.C. and Alberta and that’s because the landscape outside of there is fairly hostile for caribou,” he said.

Changing the way land use and wildlife decisions are made more broadly is something the Kaska Dena have been pushing for as well, said Norm MacLean, a senior wildlife biologist with the environmental consulting firm LGL Limited and a technical advisor to the Dena Kayeh Institute.

The province struggles to adequately monitor caribou and other wildlife given the pace of resource development. Meanwhile, “we have this wealth of knowledge sitting with Kaska and other nations,” MacLean said.

A start would be making decisions together in a way that respects “Kaska knowledge and laws and stewardship principles,” he said.

Though northern mountain caribou have special concern status under the federal Species at Risk Act, Ray says that standing conveys little additional protection.

While a management plan was created over a decade ago, there are no signs of an update and none of the measures included are binding, she said.

One purpose of the act is to ensure that species of special concern don’t become threatened, but Canada has a poor track record of preventing that progression, Ray said.

The new assessment report offers several recommendations to help reduce the chance that northern mountain caribou will tip into the threatened category.

Alongside the need for political commitments to prioritize caribou conservation, the report calls for better monitoring of caribou populations and tracking of human impacts to caribou habitat.

At the same time, the authors recommend these 17 populations and ranges be managed as a unit, the idea being that “the land management and habitat disturbances on one caribou range are considered in terms of their implications to the whole system, rather than just to the individual caribou population and range.”

“We know from experience in southern BC and other areas that recovering caribou populations once they are declining is very difficult and expensive,” they wrote. “In northern B.C., we still have the ability to take simpler and much more effective steps to conserve caribou if we act now.”

Updated on July 21, 2022, at 8:35 a.m. PT: This story has been updated to clarify that the researchers of the report are not all Wildlife Conservation Society Canada staff members.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...