Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

Andrew Dialla was six or seven when his grandmother passed away. He grew to know her through stories of her deep love for the land — how she would spend hours out on walks, collecting “pretty things” in her pail.

“The main thing I always heard about her was her collecting stuff on the ground all the time,” Dialla recalls.

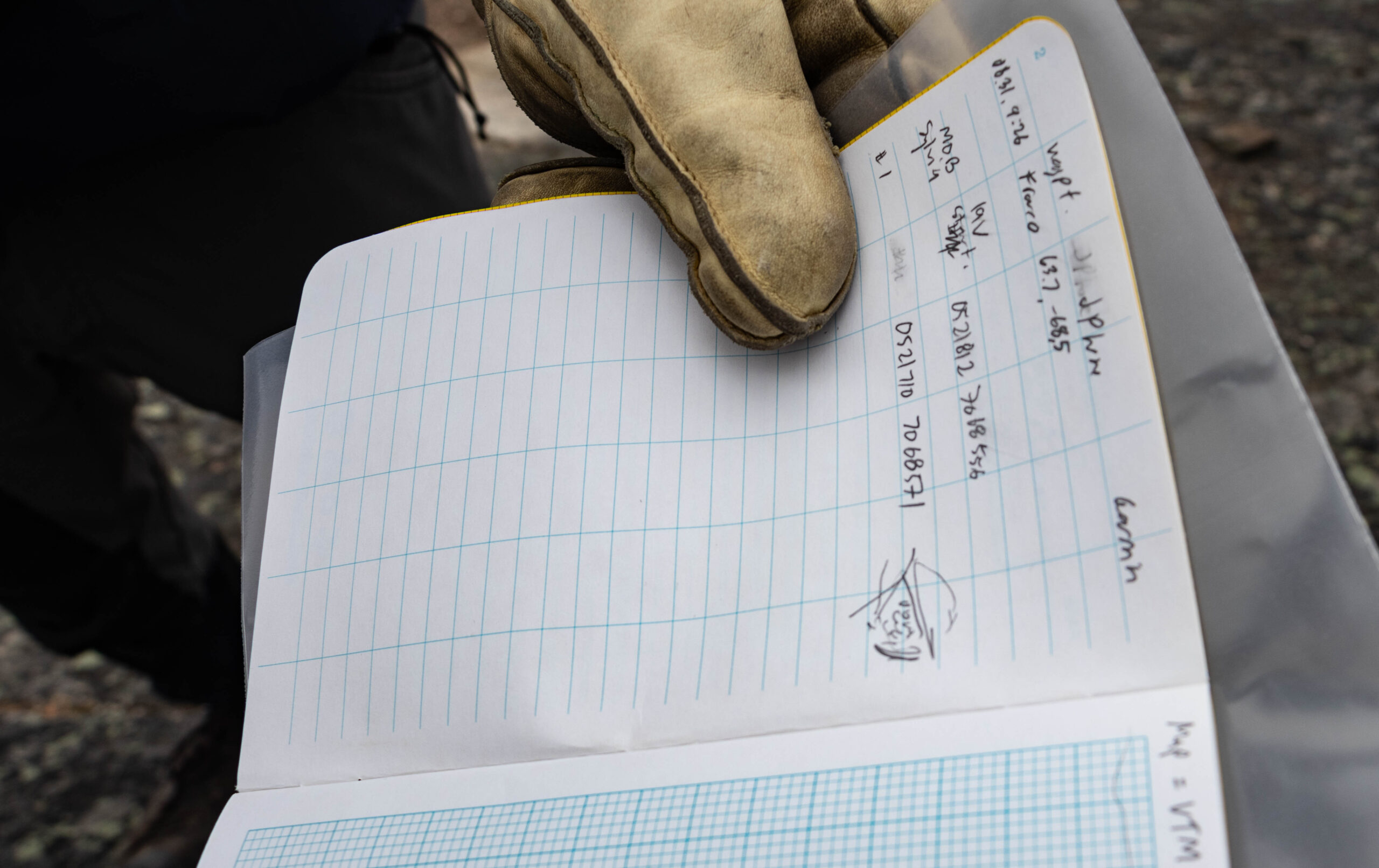

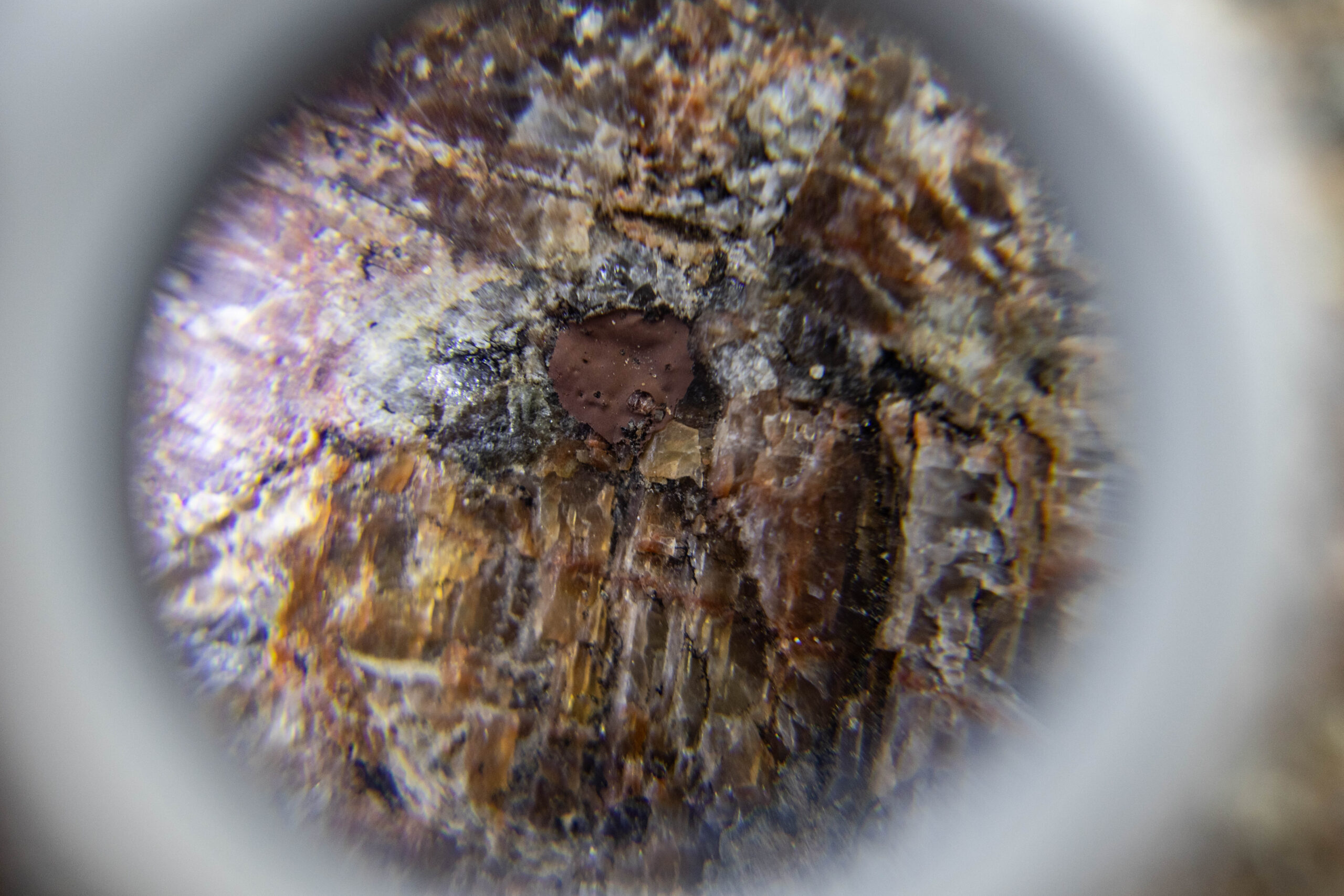

Dressed in a beige camouflage jacket and carrying a magnifying glass, Dialla is squatting down to look at the rocks around him. He’s taking part in an introductory prospecting course led by the Nunavut government’s geology department. Along with 10 other people, Dialla has spent a week at the local Franco Centre and Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park, at the edge of Iqaluit on southern Baffin Island, learning about a lot more than just rocks.

As an industry, mining is already the largest private-sector employer of Indigenous Peoples, both in Nunavut and across Canada. Many Inuit receive some compensation from the industry through the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which defines Inuit-owned parcels of land — on which the three mines currently operating in the territory are located.

Yet few Nunavummiut prospect and explore themselves, and there are no Inuit-owned private exploration companies in Nunavut at this time.

Now in its 25th year, the Nunavut Prospectors Program aims to engage more Inuit in the business of mining. With the courses held in at least three communities, the hope is to train, certify and fund Nunavummiut to go out to explore, prospect and stake claims on their land safely, effectively and as ethically as possible.

On the cool day in August, in Sylvia Grinnell park at the shore of Frobisher Bay, Dialla is brushing up on some well-practiced skills in prospecting.

Just last summer, he went out with his nephew around their hometown of Pangnirtung to double check areas he had visited in the past for gold or diamonds.

“I spent a few days climbing mountains and basically suffering because the land where I was is like walking on a mattress,” Dialla says.

“You really have to be passionate if you want to do this, because it’s hard work. It’s not just walking around and touring around. You can bend over a lot and you grab a lot of things. And you’re out on the land so you have to be careful,” he says. “It’s always better to call a partner. When I’m looking through the magnifier, my partner can be looking around for polar bears.”

A licenced prospector since the ’90s, Dialla took the course to refresh his memory — and it also revived those of his grandmother. A lot has changed in the years since.

In general, the mining industry has seen massive growth across the North and is considered to be the largest private sector contributor to each territory’s economy, according to a 2024 report by the Mining Association of Canada.

In 2022, mining contributed 41 per cent to Nunavut’s gross domestic product. And yet, according to Maryam Abdullahi, a geologist and currently the senior petroleum advisor for the territorial geology department, Nunavut is considered by industry and government to be one of the most underexplored places in Canada, for mining purposes. She is teaching the prospecting course in Iqaluit this year and says, shorter field seasons, the lack of road access and sheer expense influence both the interest in mining in the territory and the market’s appetite for it.

“Here, even in summer, you’re at the mercy of the weather. You have two months to work and you have to fly everything in, which is why in terms of competitiveness and the amount of companies that will come in, it is difficult,” Abdullahi says.

“Any company that comes in will be a company that has a lot of money, will be a company that has a lot of investors that have very high confidence in Nunavut, and will be a company that probably has a strategic reason to be here.”

“In terms of how much potential Nunavut has, I can’t quantify that because to be able to quantify potential you need to have a lot of exploration done,” Abdullahi says.

The fact that Nunavut is heavily under-explored affects how much we understand about it, she says. Whoever can gather that information also has the power to use it. And that presents an opportunity for Inuit to have more control.

It may be yet-unquantified, but “we have a lot of potential,” she says.

Nunavut is already known for gold exploration and a vibrant base-metal inventory that includes lead, zinc, copper, silver, critical minerals and rare earth elements, Abdullahi says. Some of these are necessary components in key technologies for the shift to clean energy, including batteries.

“Nunavut has 22 of the 31 critical minerals that have been listed by the Government of Canada and the United States as the minerals there are significant in order for the energy transition and decarbonization to happen,” Abdullahi says.

The introductory prospecting course aims to equip participants with a base knowledge of the geology of Nunavut, as well as the necessary steps to take once an exploration site has been discovered or established.

Over the course of the week-long program, this means recognizing igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks and knowing how to differentiate them based on how they look, smell and feel.

As well, participants learn how to use field equipment such as a compass, a GPS and local maps to identify and confirm locations. The program also includes instruction on the groundwork and paperwork required to stake a claim through an online portal.

In the past five years alone, 103 Nunavummiut — both Inuit and non-Inuit — across 15 communities have received their prospecting certificate.

Since 2019, 16 people have also applied for $8,000 grants from the Government of Nunavut to secure prospecting claims.

The program helps Inuit help industry by engaging in exploration in their backyard, Abdullahi says.

And yet, long-term exploration is expensive and time consuming, which means it is easier carried out by a company than it is by an individual.

“All it takes is one guy to find something good and get a mining company interested in it,” Dialla says. He keeps that in mind when he explores in his home community, where many Inuit continue to live off the land but don’t necessarily make a living from it.

“The reason why I’m trying my efforts in the Pangnirtung area is because it’s my hometown and, talking to a bunch of people there, I really found that Pangnirtung needs something else other than fishing,” he says.

“If there could be a mine opened up nearby, or kind of nearby, that would create a lot of jobs.”

It is also a way to apply age-old skills and knowledge of the land in newer ways.

“[It’s about] looking at the land and not looking for animals on the land, and that takes a lot of getting used to,” Dialla says.

“I realized a few times looking through the binoculars that I’m not supposed to be looking for caribou here, but I’m looking for caribou,” he says. At the same time, he adds, most hunters have a story about being out on the land and seeing a particularly interesting rock.

For William Rowsell, a first-timer in the prospecting course in Iqaluit, it’s a full-circle moment following a childhood of collecting rocks.

Rowsell was raised in Kinngait, formerly called Cape Dorset and hailed as the “most artistic community in Canada” and the “capital of Inuit art.” Rowsell remembers going out on the land with his father to collect soapstone for others to carve.

These days, Rowsell’s son comes along to collect rocks in Iqaluit, where they now live. It is one of the reasons Rowsell took the course, “to regain the knowledge” and have more to teach his son.

“I honestly had forgotten about everything that I learned in geology in high school, and not only in high school but in life when my father was teaching me about rocks,” Rowsell says.

The course roused other memories from his childhood: of a giant patch of orange rock in Kinngait on which he and his friends would play.

“Some Elders had expressed to us that we shouldn’t be playing there, in case lightning ever strikes it again. At the time we thought about how we don’t have lightning or thunder [in Kinngait],” he says. Then he learned about gossans, a type of highly oxidized rock that’s often the weathered top of an iron or other mineral deposit. He realized, “this looks very familiar to what I used to play on with my friends.”

Scientifically speaking, metals do conduct lightning.

“Those Elders could have been spot on with their stories,” he says. “They knew it and they told stories in order to deter curious kids like we were away from spots they’re not supposed to be in.”

Should that orange rock be unclaimed, Rowsell says he is unsure if he would stake it because claiming that land may not align with Inuit values and his community’s interests. “I love geology but it’s not like that passion to a point where I’m going to focus my entire life to mine something, especially when it’s also not in line with my culture,” Rowsell says.

“I understand that it would be great for the economy in Kinngait, considering it would create jobs and it would create that spark. But I also believe it would take away from the fact that Kinngait is still known for its art. Instead, it would be known for a giant mine right in the middle of town.”

But putting mining operations in the hands of Inuit could help steer the project by those values. While such ownership doesn’t yet exist in Nunavut, over its border in the Northwest Territories, DEMCo Ltd. is a fully Dene-owned exploration and mining company. In the Yukon, Selkirk First Nation recently purchased the abandoned Minto mine, and may seek to reopen it.

The recently signed Nunavut Devolution Agreement will come into effect in 2027, and will transfer responsibility for lands and resources from the federal government to the territory. In that context, both Abdullahi and Nunavut’s Minister of Economic Development and Transportation, as well as Mines, David Akeeagok say more Inuit need to have the necessary education and training to get involved in mining and make decisions for the industry moving forward.

“If you know big mining companies, when they need those minerals, they’re going to start looking for them,” Akeeagok adds. In Nunavut, the proper training can allow Inuit to take the lead.

“As Inuit, we’ve always advocated that you need to balance the stewardship of the environment and the extraction,” he says. “But when you’re not able to make decisions about the extraction process, then that balance is off.”

For Dialla, from Pangnirtung, his grandmother’s legacy is a part of what brings him out to the prospecting course.

Back when his family was still moving between camps with the seasons, one story goes that his grandmother was walking around one day and found rocks “that looked like broken glass and some of them were round,” Dialla recalls. She picked them up and put them in her pail.

When Dialla’s grandmother tried to rinse them later, the transparent rocks nearly disappeared under the water. She told her husband or another family member about it. They took some of the rocks and scratched them against a mirror in the sod house.

The mirror broke right away, shocking everyone there.

“Grandma didn’t know anything about diamonds … she’d never heard of them,” Dialla says. “But listening to her description of the clear rocks that she collected, we always thought they had to have been diamonds.”

The family believes their spring camping spot, so many years ago, was nearby the current Chidliak diamond exploration site, owned by De Beers.

The family has looked for those rocks in the years since. Dialla says his sisters even tried returning to the spring camp and the qammaq, or sod house, northeast of Iqaluit, where his grandmother had left them when the family migrated again for the summer. But after so much time passing and so many changes to the land, they have had no luck finding it.

“Grandma’s diamonds were never found,” Dialla says. “They’re still there.”