The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Hilu Tagoona was six years old when her mother brought her on a caribou hunt along Baker Lake, just south of their community of the same name. They walked up a hill together and spotted a caribou resting on the ground. Her mother instructed Tagoona to crouch down and they crept around the animal to get upwind. They could tell the caribou noticed their presence, but it didn’t move. Just curious. Tagoona’s mother quietly told her to cover her ears. Then she shot the caribou with her rifle.

Tagoona started to cry, and her mother told her she shouldn’t mourn this as a loss, but rather see it as a gift. We need the caribou to survive, she said, and we’ve had a respectful relationship for thousands of years.

“It’s always stayed with me that we must respect them and make sure that we care for them, so that we can continue to have this gift of being able to sustain ourselves and have food sovereignty,” Tagoona says.

Since Baker Lake is Nunavut’s only inland community, the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq caribou herds that pass through the area are especially important to residents — there are no marine mammals to rely on.

Just as Tagoona learned this at a young age, she learned of the mineral potential near her community and the desire to mine it. Her mother has been outspoken about the need to protect caribou habitat and Tagoona followed her lead. She’s a MiningWatch Canada board member, and a member of the non-profit Nunavummiut Makitagunarningit, which has advocated against uranium mining near Baker Lake.

“I think a lot of Nunavut has been safe from many things due to the remoteness, the extreme temperatures and that has created a safe haven for a wonderful ecosystem including caribou, which is very much a northern species and very much a symbol of Canada,” she says. “We feel a big responsibility to protect those areas.”

Today, the Amaruq gold mine operates 125 kilometres north of Baker Lake, part of Agnico Eagle’s Meadowbank Complex. Three more mines — extracting gold and iron ore — are in operation in other parts of the territory. According to a November 2020 overview, there are nearly 2,500 mineral claims in Nunavut, about 500 leases and 130 prospecting permits, targeting copper, diamonds, gold and iron ore.

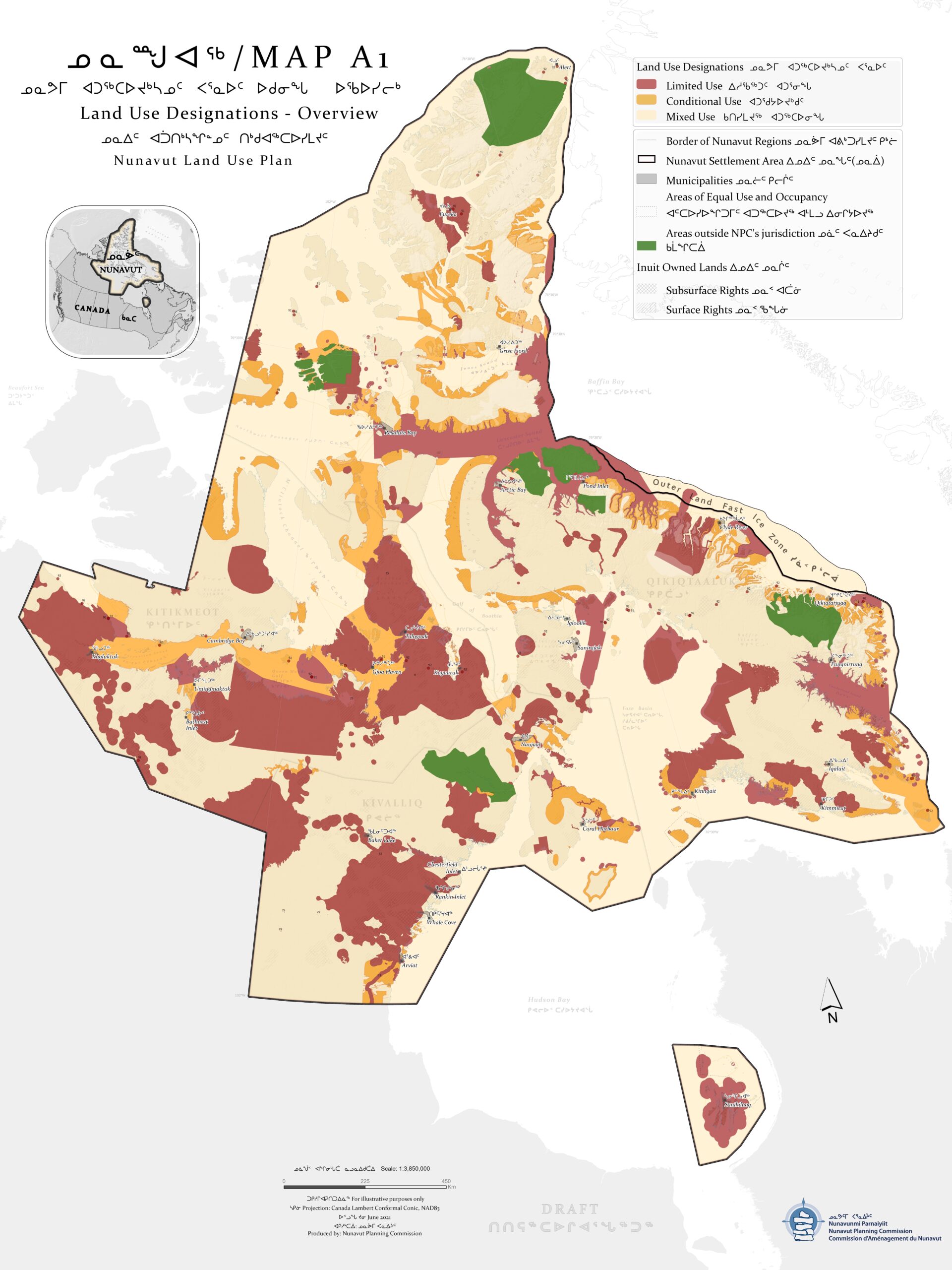

Tagoona’s focus now is the Nunavut land use plan, which will create a framework for the future of the territory, determining which types of development can happen and where, and outlining where environmental protection is a priority above all. Across Canada, land use plans tend to be developed on a regional basis, rather than province or territory-wide — making Nunavut’s all the more sprawling.

The document has been years in the making, with the latest — and potentially final — draft released last summer. It’s a massive undertaking, and not only because Nunavut comprises one-fifth of Canada’s land mass.

The region is where many competing issues overlap — where Inuit value culture, tradition and the health of the landscape and its wildlife. Where unemployment is high and the ground holds mineral and oil and gas deposits. Where barren-ground caribou populations are declining dramatically and climate change is being felt most acutely, causing sea ice to disappear and affecting humans and wildlife alike. Where fewer than 40,000 Nunavummiut live in 25 communities, only accessible by air or sea.

“The geographic coverage and the range of issues addressed is without precedent, not just within Canada but internationally,” the Nunavut Planning Commission wrote in a 2021 backgrounder on the land use plan. Canada is also one of the few countries that still has large, relatively intact landscapes.

“I would say there’s a large responsibility not just to Nunavut, to Canada, but to the whole planet to get this right and to support these Indigenous-led efforts,” says Paul Crowley, a lawyer and consultant in Iqaluit who’s involved with Friends of Land Use Planning, a group that supports Indigenous-led land use planning in Canada. “If this comes to pass, it will be, I’m told, the largest regional land use plan in the world.”

Back in 1993, the Canadian and Northwest Territories governments and what was then called the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut — representing Inuit of the Canadian eastern Arctic — signed the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Now simply referred to as the Nunavut Agreement, it’s the largest land claim in the country, covering 2.1 million square kilometres that fell within the borders of the Northwest Territories at the time. It gave Inuit a role in co-managing the environment, harvesting rights, a portion of government revenues from resource development and federal money transfers in order to establish a territorial government.

In 1999, Nunavut was officially created, separate from the Northwest Territories. By 2025, Nunavut’s devolution is expected to take place, with the federal government handing responsibility over land, water and resources to the territory.

The Nunavut Agreement established institutions to oversee resource development and any impacts on the land and water, including the Nunavut Planning Commission, which operates independently of government but receives federal funding. Under the agreement, a land use plan for the territory is a legal requirement.

Paul Quassa was sitting next to then-prime minister Brian Mulroney back in ’93 when they both signed the Nunavut Agreement. Quassa was chief Inuit negotiator and president of Tungavik Federation of Nunavut, which now goes by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. and operates independently of the territorial government; he went on to chair the Nunavut Planning Commission from 2006 to 2013. Now he is a senior advisor for Baffinland Iron Mines Corp., which operates the Mary River mine on north Baffin Island. The ultimate goal of the land use plan, he says, is to protect the environment and wildlife, while allowing for economic development.

“The Nunavut Planning Commission’s role is to ensure that they listen to all,” Quassa says. “It’s also very clear in the Nunavut land claims agreement that special consideration has to be [given to] Inuit, Inuit culture, and I think that’s a very important provision in there.”

The road to a land use plan for Nunavut has seen its share of bumps. Regional land use plans were already well underway in 2005, when the federal government said they’d no longer be considered. Once work on the territory-wide plan began in 2007, public hearings and meetings across Nunavut followed, which then came to another halt when former prime minister Stephen Harper’s federal government refused to fund the final round of hearings. In 2014, the commission sued the Harper government for interfering with its process but dropped the lawsuit the following year in hopes of coming to an agreement.

The federal government has provided an average of $5.5 million per year for the planning process, including the cost of holding community hearings, plus an additional $10.9 million between 2016 and 2021 under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government. There’s been hundreds of filed written comments and four draft plans in all.

Once the three signatories — the federal and Nunavut governments and Nunavut Tunngavik — approve the plan, it becomes legally binding. It’s a living document, though, not intended to be set in stone. It will be reviewed regularly by the commission.

This latest draft sets out three main land designations: limited use, conditional use and mixed use. Limited use makes up 22 per cent of land; there are year-round prohibitions “on one or more types of land use.” Conditional use areas make up nine per cent, and have requirements, like seasonal prohibitions on certain activities. Mixed use comprises 65 per cent, with no prohibited uses or conformity requirements. Aside from specific projects that would be grandfathered into limited-use areas, mining and other industrial development is only permitted in conditional use and mixed use areas.

The plan designates caribou calving and post-calving grounds, key access corridors and some freshwater crossings as limited use.

Caribou in Nunavut are in trouble. Most of the territory’s herds have seen steep declines in recent years. The Bathurst and Baffin herds, for instance, have each decreased by 98 per cent over the last 30 years. In some communities, Inuit are shouldering hunting restrictions.

At previous community consultations, an overwhelming majority of attendees said they wanted these areas off-limits to industrial activity year-round to minimize disruption to caribou.

“If you travel to communities, which I’ve done extensively, you hear that this plan is reflective of what people want to see,” says Brandon Laforest, senior specialist of Arctic species and ecosystems at World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Canada. “So I land in a place that this is a good plan.”

Not everyone thinks so. Some parties have taken issue with the amount of land designated as limited use — up from 15 per cent in the 2016 draft, due to a push from communities.

“The increase in prohibitions is an unacceptable risk to Nunavut’s economic opportunities,” wrote the Nunavut government in its October submission to the planning commission.

Agnico Eagle, who extracted nearly 530,000 ounces of gold from its two Nunavut mines in 2020 and acquired a third mine in 2021, suggested that the assumption that protecting caribou habitat “will support continued levels of abundance and aid in the recovery of declined herds” was “erroneous.”

“There is a view (which we believe is unsupported) in the 2021 [land use plan] that development is detrimental to migratory caribou abundance to the exclusion of other factors,” the mining company wrote in its submission to the planning commission. “This view is derived from southern Canadian experiences and evidence associated with non-migratory Boreal caribou.”

Instead of broad geographic-based prohibitions, the mine’s submission posited that mitigation measures that “travel with the caribou” and kick in once they’re present would be enough, such as closing the road to the mine when caribou approach it or suspending outdoor operations like drilling, blasting and use of helicopters when more than 50 caribou are within five kilometres of the mine site. Agnico Eagle declined an interview request for this story.

Laforest disagrees.

“I would flip that and say if you don’t protect the calving grounds, then you’re almost guaranteeing they’re not going to come back,” he says. “It is an industry tactic to undermine the importance of habitat protection.”

Laforest points to the fragmentation of boreal caribou habitat — and the decimated populations — in the provinces. “Every approach to caribou conservation is anchored in habitat protection for critical areas,” he says. “From a barren-ground caribou perspective, this is a chance to get it right and a chance to avoid the problems we’ve seen in the south.”

He adds that mobile protections are unproven and unfeasible, given the amount of monitoring that would be required. The measures could be tested along migration routes, he says, but they just aren’t appropriate in critical calving areas.

Ross Thompson, executive director of the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board, adds that no one’s saying industrial activity is solely responsible for herd decline — the problem is cumulative effects.

“The herds are being assailed from everywhere, all points of the compass,” he says, listing industrial disturbance, harvesting, predation and climate change as a few examples. “If the habitat is not healthy and vigorous and extensive, then that will impact the ability for a population to rebound.”

Another subject of disagreement has been what to do with existing mineral rights in critical caribou habitat. The latest draft plan grandfathers in certain rights in limited-use areas, though if these projects seek to expand or modify operations, they must be reviewed by the commission to ensure that the changes are in keeping with the plan.

Both the federal government — which holds most of the territory’s subsurface rights and thus receives mine royalties — and the NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines have recommended the plan recognize all existing mineral rights. Yet many people remain concerned about any industrial activity in areas designated limited use.

“Our argument is why not protect those areas altogether, because even if exploration is occurring during those times [when caribou aren’t present], exploration is only in hopes to find development opportunities,” says Hilu Tagoona in Baker Lake. To her, and others, economic development and habitat protection can co-exist — but caribou are the top priority.

“There’s two million square kilometres of land,” says Paul Okalik, a former Nunavut premier who also helped negotiate the Nunavut Agreement and is now Arctic specialist at WWF-Canada. “There’s plenty of land for everybody. Just those areas where we feel the caribou should be protected are what we’re focusing on.”

This is why having a finalized plan should benefit everyone. For industry, it will provide clarity around which areas are open for development and which are not — a road map to avoid conflict with communities. It is, after all, a land use plan, not solely a conservation plan.

A signed plan could also be an opportunity for Nunavut to contribute even more to Canada’s international commitment to protect 30 per cent of its land and water by 2030 — on the territory’s terms. Already, Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq, two marine protected areas, make up more than half of the 14 per cent of Canada’s oceans that have some form of protection. In 2020, then-Nunavut premier Joe Savikataaq said his government wouldn’t support any more federally protected areas in the territory until a devolution agreement is reached. He accused Canada of using the territory to meet federal conservation goals while undermining Nunavut’s ability to make decisions about its own lands and resources.

Based on the criteria that outlines what areas qualify under Canada’s conservation target, it seems that some of Nunavut’s limited-use areas — which total 440,000 square kilometres (altogether a little less than the area of Baffin Island) — would count towards the federal target.

At the end of 2020, Canada had protected 12.5 per cent of its land and freshwater — about 1.1 million square kilometres (or nearly the equivalent of the entire province of Ontario). The country still has a long way to go to meet its conservation targets and the potential addition of Nunavut’s limited-use areas would nudge that number up to about 17 per cent. But it’s not clear that the entirety of these areas would qualify. For one thing, the land use plan will be amendable, which suggests that its protections would be as well, and a key part of the conservation criteria is longevity.

Residents of Taloyoak have a vision. They want to create an Inuit Protected and Conserved Area around their community on the edge of the Boothia Peninsula. Called Aviqtuuq, the area is home to caribou, muskox, bowhead whales, seals, narwhals and migratory birds.

In addition to protecting the wildlife that use the area, the Spence Bay Hunters and Trappers Association wants to explore sustainable, Inuit-led activities like small-scale fisheries, outfitting camps and tourism. Over the years, the association has made it clear to the planning commission that Aviqtuuq should be off-limits to industrial development — the latest draft designates it limited use.

“We’re happy with the new plan,” says Jimmy Oleekatalik, the association’s manager. “The Elders in the past always wanted [that area] protected.”

But in February 2021, Laforest, who’s been working with the association to advocate for Aviqtuuq’s protection, learned the federal government had issued two new mineral claims there that month. He says people in Taloyoak were upset, but since the plan is still in draft form, the land is technically open. WWF-Canada has called for Ottawa to stop issuing claims in areas set for protection, Laforest says, but to no avail.

As it stands, it seems these two claims won’t be grandfathered into the land use plan — they’re not listed in the draft’s appendix of exempted projects. But Laforest is concerned about a statement in the draft that the commission may amend the appendix from time to time, “as it is expected that proponents will refine the areas in which they expect to undertake mining activities and abandon rights to other areas … ”

In an email, Jonathan Savoy, the commission’s director of policy and planning, wrote that commissioners — eight community members appointed by the federal and territorial governments, Nunavut Tunngavik and the three regional Inuit associations — would decide whether to revise the appendix to include additional mineral rights after the next round of community hearings, scheduled for March 2022.

Next year will be the 15th in the planning process. There’s a sense of urgency among people on the ground in Nunavut, a feeling that, until the plan is approved, it’s open season for mining companies and the future of the caribou is even more tenuous. Okalik, for one, is frustrated there’s no plan yet in place.

“I would have thought that we would’ve had this plan 25 years ago,” he says. “This is a treaty that should be honoured by all parties and it should be implemented already.”

He doesn’t want to speculate about whether that will happen in 2022.

“We’ve waited 30 years — I don’t want to put forward expectations because I don’t know how much time we’ll wait. So I’ll just wait for the day and have a celebration when it takes place.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...