Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

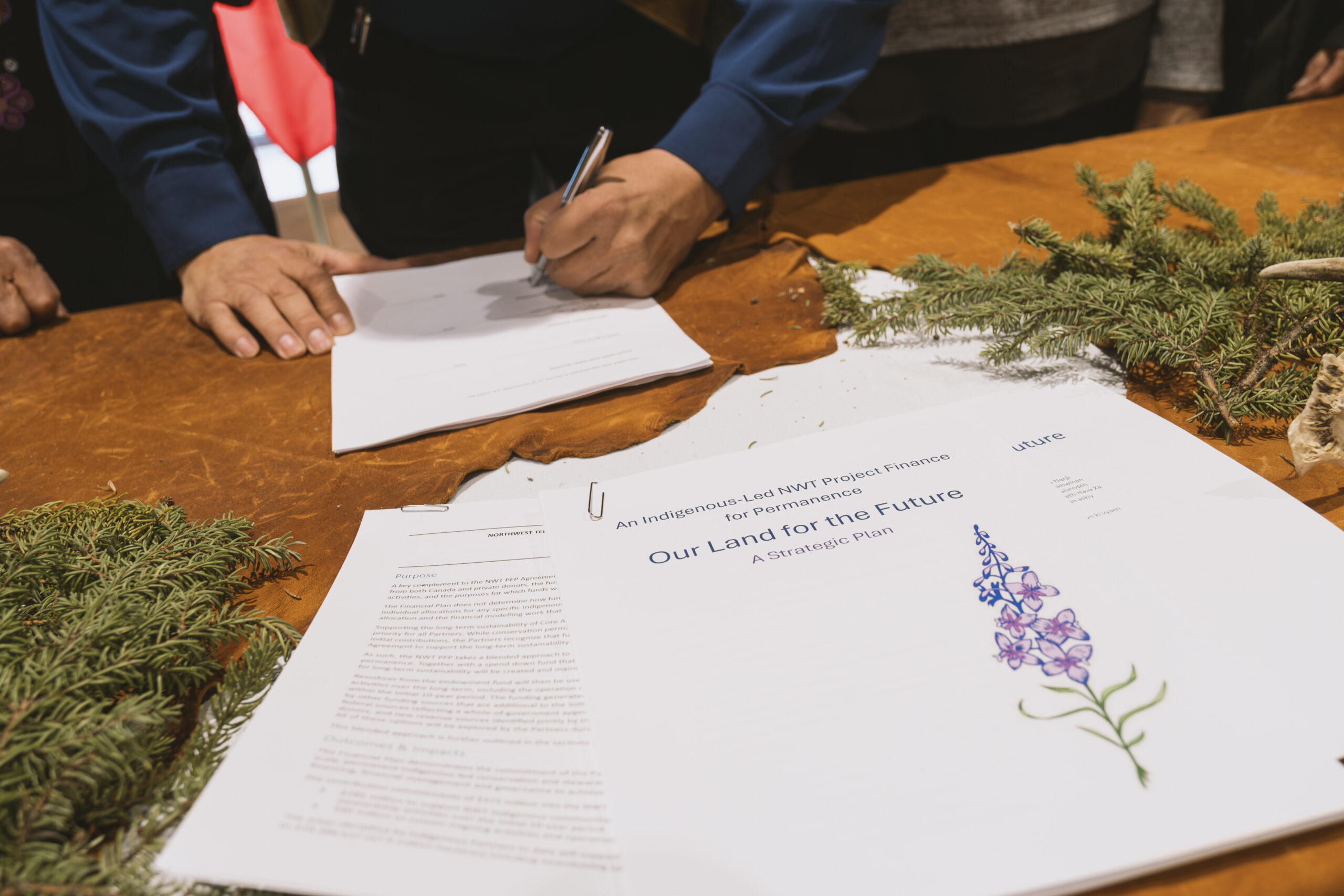

On a wintry morning in Behchokǫ̀, a community roughly 100 kilometres northwest of Yellowknife on the shore of Great Slave Lake, leaders of more than 20 Indigenous governments and organizations from across the Northwest Territories gathered for a day of speeches, jigging and drum dancing. They were joined by representatives of Crown governments, philanthropists and community members, including toddlers, teenagers and Elders. The crowd had assembled to celebrate the signing of one of the largest Indigenous-led land conservation agreements in the world.

“Today is a big day,” Danny Gaudet, Ɂek’wahtı̨dǝ́ (elected leader) of the Délı̨nę Got’ınę Government, said at the Nov. 14 celebration.

The event, which took place at the Behchokǫ̀ Cultural Centre, opened with a fire-feeding ceremony on the edge of a frozen lake. Later, attendees moved indoors, where they listened to leaders’ reflections on the occasion, shared a lunch and, finally, pushed aside the tables and chairs to dance under a large drum-shaped light fixture.

“We’ve been removed from the land for 100 years,” Gaudet told the assembled crowd of more than 200. “This signing allows us to go back. It will help us go back to our traditions and our culture.”

The agreement, known as NWT: Our Land for the Future, provides $375 million to support Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship activities, including the establishment of new protected and conserved areas, Guardian programs, ecotourism, traditional economic activities and climate research, among others.

The deal combines $300 million from the federal government with $75 million from private donors, using a funding model inspired by practices employed by bankers and Wall Street executives — as far from conservation efforts as they may seem.

Altogether, 22 Indigenous governments and organizations signed the agreement — representing the majority of Indigenous nations in the territory — along with the federal government, the Government of Northwest Territories and private donors.

This level of collaboration is rare. Several attendees commented on how they had seldom, if ever, seen so many N.W.T. leaders in the same room.

The expanse of protected and conserved areas that could come out of the agreement is huge. By funding the management of existing protected areas and the establishment of new ones, the deal has the potential to cover roughly 380,000 square kilometres. This includes approximately 200,000 square kilometres of new protected and conserved areas, which is roughly the size of Great Britain.

“That’s how much is at stake here, and that is why I think this is such a historical moment,” Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Gary Anandasangaree said.

The new conserved areas would contribute more than two per cent to the federal government’s commitment to protecting 30 per cent of Canada’s land and inland water by 2030. It would bring the total protected area in the territory to more than 412,000 square kilometres, or more than 30 per cent of the territory.

The agreement, however, is about a lot more than protected areas, according to Dahti Tsetso, deputy director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, an organization that supports Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship. Tsetso played a key role in convening the agreement’s partners and facilitating negotiations.

“It’s not just about the hectares, it’s really about the people,” Tsetso said.

The funds mean Indigenous governments will be resourced for their stewardship and conservation work, she said, which might involve establishing or growing Guardian programs and implementing cultural or land-based programming.

These activities have a big impact, according to Tsetso. Young people will have examples of leadership to look up to, she said, which could catalyze interest in further education and promote community healing.

The agreement, she told The Narwhal, “has so much transformative potential.”

As the funds are dispersed over the next decade, the initiative is also expected to support hundreds of jobs each year. It will provide opportunities for economic diversification by bolstering a conservation economy and building up Indigenous governments’ capacity to engage with industry and regulators, thereby supporting a balance between conservation and development.

“It’s the beginning of a new journey for our nation,” Tłı̨chǫ Grand Chief Jackson Lafferty said at the gathering.

Addressing the room in Behchokǫ̀, Dehcho First Nations Grand Chief Herb Norwegian said, “We are going to create something totally beautiful, something totally unique.”

To reach this landmark agreement, signatories used an innovative approach to conservation finance known as project finance for permanence, or PFP.

The agreement, also known as the NWT PFP, is one of four initiatives using the project finance for permanence model announced by the federal government in December 2022. A project in the Great Bear Sea, in British Columbia was finalized last summer, while initiatives in Nunavut and northern Ontario are still being negotiated.

The model is intended to address funding issues that often hamper conservation work.

Funding arrangements differ from one conserved area to another, but in many cases, they run on minimal public dollars and short-term grants. Effectively managing these areas over the long term in the face of inadequate and uncertain funding is a constant struggle. As one conservation leader put it in a 2012 article, “Our goal this year is to hold off disaster, and to raise the money for the next year so that we can live to fight another day.”

More than a decade later, Indigenous-led conservation still faces similar challenges.

Ts’udé Nilįné Tuyeta, an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) established in the Northwest Territories in 2019, covers a swath of boreal forest near Fort Good Hope. The protected area receives just over $200,000 per year from the N.W.T. government, according to a 2023 MakeWay report. But its annual operating budget is closer to $3 million.

“We’re just kind of going on the fly with whatever funding we have now,” Daniel Masuzumi Sr. said. Masuzumi is the executive director of the K’ahsho Got’ine Foundation, the management arm for Ts’udé Nilįné Tuyeta. He said he spends roughly 75 per cent of his time trying to cobble together funds.

Jessica Jumbo, who worked as Sambaa K’e First Nation’s environment and lands coordinator from 2011 to 2023, echoed Masuzumi’s comments. (Jumbo is now the director of lands and resources for Dehcho First Nations.)

“Even when you’re doing that, there’s not enough funding to keep any of your community members on a permanent, year-round basis,” she explained, which makes attracting and retaining staff difficult.

“The turnover is really high,” she added.

In 2011, a group of former investment bankers, management consultants and conservationists developed the project finance for permanence model, with the intention of providing a more sustainable approach to long-term, large-scale conservation. They drew on Wall Street practices for organizing and funding expensive, complex projects, such as dams and power plants.

In the model, partners coalesce around a shared conservation goal, laying out all the plans, funding and policy changes needed to sustain that goal’s long-term success. These initiatives typically leverage both private and public funds, with investors committing their funds upfront when the deal is closed to finance all the essential components of a project simultaneously. In this way, project finance for permanence aims to ideally provide full, perpetual funding to conservation initiatives.

This approach to project finance is common in private industry, but it is relatively new to the world of conservation. The basis for the model came from lessons learned from the Great Bear Rainforest agreements in coastal B.C. in 2006 and 2007, as well as major conservation projects in Costa Rica and Brazil. Project finance for permanence initiatives have since been explored in a handful of countries, including Bhutan, Colombia and Mongolia.

In the Northwest Territories, the possibility of applying this model of conservation financing first arose in 2021. At the time, the territory was already a leader in Indigenous-led conservation, with three federally recognized IPCAs established within its borders. These initiatives, along with Guardian programs, had demonstrated the benefits of the work, and leaders were looking for additional support. Around the same time, a group of international philanthropists formed a collaboration aimed at tackling large-scale conservation using the project finance for permanence model. Meanwhile, Canada was looking for ways to meet its 30-by-30 goal.

In 2022, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced $800 million for four initiatives, one of which was the Northwest Territories’.

Tsetso had recently come into her position with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative when she was tasked with assembling partners for the project finance for permanence initiative. At first, she wasn’t familiar with the model. Neither were many of the Indigenous partners she was charged with convening.

“At the very beginning, a lot of people had never heard of such a thing,” Tsetso recalled. The early discussions focused on ensuring everyone understood what the initiative was about.

Tsetso said another big part of the process was driven by Indigenous governments’ expectations for true collaboration.

“Literally every element of the agreement, all the advocacy efforts around it, even the public communication for this initiative, has been co-drafted,” she said. “We spent countless hours together on Zoom with everyone’s legal technical advisors, reviewing every single word, every single provision.”

“The investment of time and energy and capacity by all partners was staggering,” she said.

Given the number of partners at the table, she added, the final agreement was reached in record time.

A draft of the final agreement was tabled at the N.W.T. Legislative Assembly on Nov. 1. It lays out the initiative’s objectives, core activities, financial plan, strategic plan and oversight mechanisms.

The funds will be held by a trust. A bill to create that trust was swiftly passed in the legislature prior to the signing of the agreement at the celebration on Nov. 14.

Of the $375 million, $285 million will be directed to a conservation and stewardship fund, which will be spent down over a 10-year period. The remaining $90 million will go into an endowment fund, which will cover ongoing operational costs and, eventually, the management of established protected and conserved areas.

Exactly how the funds will be distributed has yet to be determined, but several bodies will be formed to provide oversight. All 28 signatories will appoint a representative to a partnership table to provide overall guidance on the initiative’s implementation. In addition, Indigenous governments will appoint five directors and donors will appoint two directors to form committees to oversee the fund.

Private donors include the Metcalf Foundation, The Sitka Foundation, The Waltons Trust, Ducks Unlimited, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Wyss Foundation, Bezos Earth Fund (founded by Jeff Bezos, founder and former CEO of Amazon) and ZOMALAB (co-founded by Ben Walton, grandson of Walmart founder Sam Walton).

Given the big players involved, the project finance for permanence model has sparked concerns about the interests of private donors. A project finance for permanence initiative in Chile that eventually fell through was criticized for allegedly giving wealthy donors influence over the country’s environmental decision-making.

In the N.W.T., however, participating Indigenous governments appear to be comfortable with private donors’ involvement.

“These were tough negotiations,” Steve Ellis, who represented the Łútsël K’é Dene First Nation in negotiations, told The Narwhal. “Ultimately, private donors, I think, understood that this is a place where Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination is the top priority.”

Tom Dillon, senior vice-president at the Pew Charitable Trusts, was involved in bringing together the private donors. He said the initiative’s governance is set up to give the Indigenous communities authority over decisions.

While all seven directors appointed by Indigenous partners and donors will govern the fund’s financial management, only the five directors appointed by Indigenous partners will decide how funds are distributed among Indigenous governments and organizations.

“There’s a level of trust between the community leaders and the philanthropies that goes both ways,” Dillon said.

The bulk of the funds will be spent over the next 10 years, so the agreement falls short of providing a truly permanent solution to funding challenges, Ellis said. Nonetheless, he thinks it will provide a significant leg up in terms of establishing robust stewardship and conservation programs.

With a federal election on the horizon, the project finance for permanence model will also provide stability over the coming years, regardless of potential changes to federal leadership. The Conservative Party of Canada, which is currently leading polls, did not respond to a request for comment regarding their support for Indigenous-led conservation initiatives by publication time.

Project finance for permanence “agreements have been designed to be politically agnostic of who’s in power,” Eddy Adra, chief executive officer of Coast Funds, explained. Coast Funds manages the funds from the Great Bear Rainforest agreement and the Great Bear Sea Project Finance for Permanence. Since the first Great Bear Rainforest agreement was signed in 2006, Adra said changes in federal and provincial leadership have not altered governments’ financial commitments.

In the Northwest Territories, the initiative stands to make a substantial difference over the coming decade, according to Jumbo.

Although Jumbo was not able to attend the celebration in person, she said she teared up while watching a livestream of the event.

“This means a lot for our people,” she said. The funding will help communities work toward their Elders’ vision of what protecting and working with the land should look like — something communities have been holding onto for so long, she said.

While the signatories celebrated the end of a years-long negotiating process last week, much of the work still lies ahead. As the Northwest Territories initiative moves into its implementation phase, Tsetso said oversight bodies, policies and operational budgets will have to be put in place. If all goes well, she said, the funds should start flowing next spring. Over the coming decade, partners will also be tracking the impacts of the conservation work to demonstrate its value and, hopefully, attract future investments to the initiative.

At the celebration, Gaudet described signatories as having reached a starting line rather than a finish line.

“We have tons of work to do,” he said, “and the journey has just begun.”

Editor’s note: The Narwhal has received funding through Metcalf Foundation and Sitka Foundation, which are also listed as donors to NWT: Our Land for the Future. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, no foundation or outside organization has editorial input into our stories. All of The Narwhal’s funding is disclosed annually.

Updated on Nov. 21, 2024 at 2:10 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to correct a caption which mistakenly identified Itoah Scott-Enns as her sister, Dahti Tsetso.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...