‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

When the sun rose on the final day of our 12-day hike in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and we still hadn’t seen the Porcupine Caribou herd, the reality that we might not see caribou at all was beginning to sink in for many of us, and the collective mood was sombre.

A team of photographers, artists and Indigenous leaders had been assembled by the International League of Conservation Photographers to document the herd’s epic migration — one of the longest and harshest of any land mammal.

For the bulk of the trip, as we hiked across tussocky tundra, baren shale mountainsides and frigid Arctic rivers in search of caribou, we took the opportunity to document the myriad other flora and fauna that make up this unique ecosystem, while reflecting on the unexpectedly cold temperatures that were foiling our plans.

An unusually cold spring and summer in the northern reaches of the Yukon and Northwest Territories meant the herd’s usual migration through the safety and comfort of Alaska’s coastal plain was disrupted and rendered unpredictable.

Slightly warmer temperatures are needed to spark the mass migration of this herd that begins their near-mystical journey — one of the longest and harshest of any land mammal — for the most prosaic of reasons: fleeing a seasonal plague of mosquitoes.

We were, rather perversely, praying for a swarm of distant pests.

By day 11 we reached the edge of the Hulahula river, where, in two days time, we were scheduled to be picked up by a bush pilot.

Spirits were low as we awaited the plane. Eleven days and neither hide nor hair of the caribou we had come to see.

Then, almost miraculously, as we finished breakfast on that last day, a group of paddlers sent word of the unimaginable: thousands of caribou sighted a mere 20 kilometres from our camp.

That brief satellite message would send us scrambling 19 hours straight over harsh terrain and through a dense fog — into which one member of our party would eventually disappear.

The Hulahula river flows north to the Beaufort Sea, from the Brooks range mountains in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

Each year, the Porcupine caribou herd embarks on one of the longest migrations on earth. From the northern reaches of the Yukon and Northwest Territories, they make their way to the relative safety of Alaska’s coastal plain where, by late May, they calve and nurse the next generation.

I was lucky to witness the herd’s migration in the Yukon in the summer of 2016. It was a revelation to see thousands of caribou stream by at close range over the course of a few days. What struck me most then was the realization that those six-week-old calves had already journeyed 200 kilometres or more in their short lives.

Since that time, the news has been both good and bad for the herd. The Porcupine is the only barren-ground caribou herd across the north that is not in steep decline.

However, while the caribou themselves know no border, the American political climate and details buried in a controversial tax bill have created a crisis for the herd and the Gwich’in people who span northern Canada and Alaska and have depended on them for tens of thousands of years.

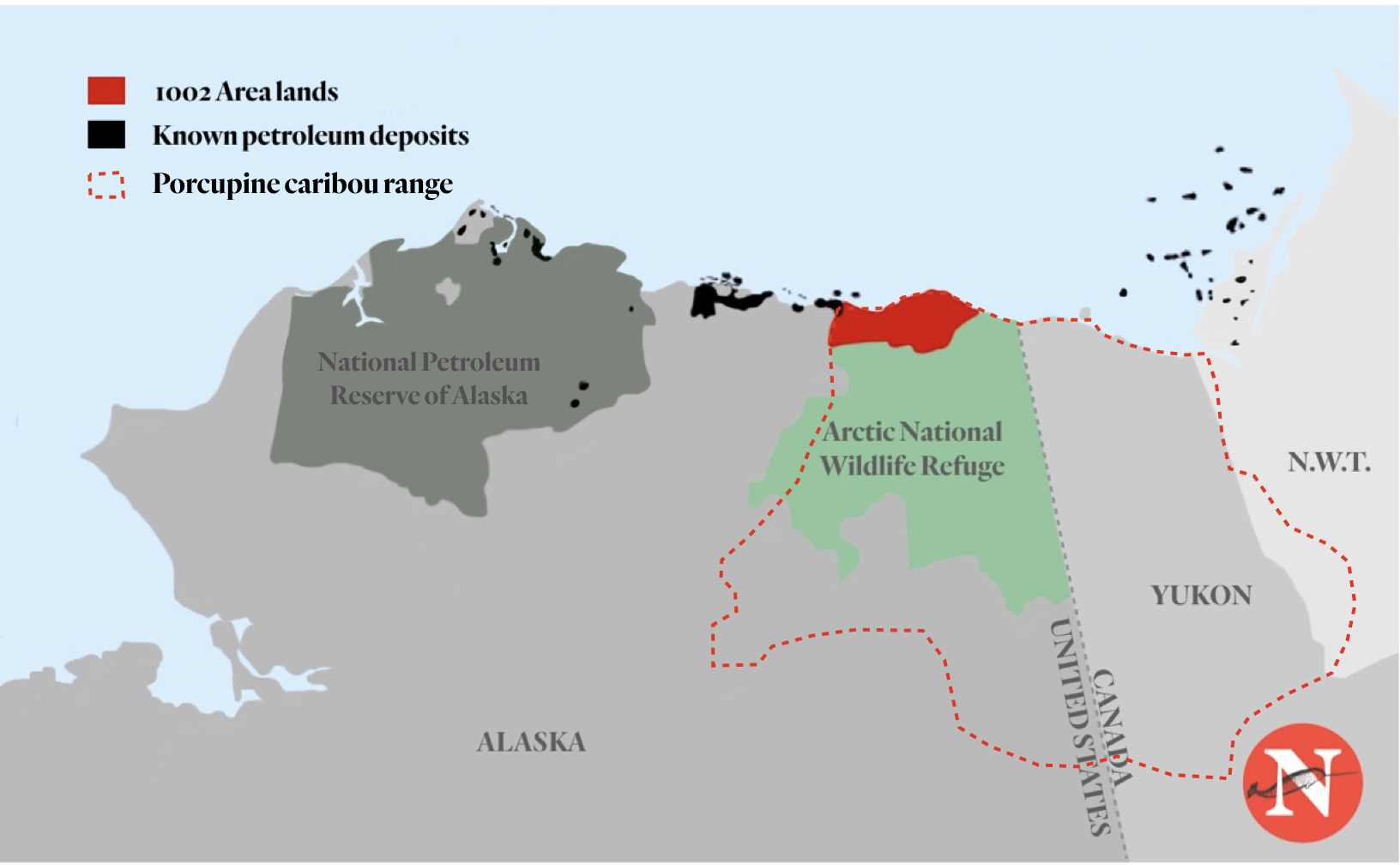

The ‘1002 lands’ of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge align almost perfectly with the caribou’s traditional calving grounds and Trump’s ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017’ has suddenly opened up this slice of untouched Arctic wilderness to oil and gas developers, after a decades-long battle with the Gwich’in First Nations and members of the scientific and conservation communities.

Map showing overlap of 1002 area lands and the Porcupine caribou herd range. Illustration: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

I recently made my way to Fairbanks, Alaska, to join a team of photographers and artists with the International League of Conservation Photographers, as well as Jeffrey Peter, member of the Vuntut Gwich’in First Nation from Old Crow, Yukon.

“There’s a lot at stake here,” Peter said, adding his experience of becoming a father for the first time had altered his perspective on the caribou, making him take stock of the legacy he hopes to pass on to future generations.

“I’ve always been concerned about the issue, but now I’m at a point in my life where I’m able to clearly describe why the caribou are so important to Gwich’in, and help others understand that.”

For the Gwich’in, the fight to protect and prolong the life of this wild herd is no less than existential.

Jeffrey Peter surveys the landscape for signs of caribou and other wildlife in the Brooks Range mountains. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

Bernadette Demientieff, the U.S. executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, works on behalf of the collective of First Nations to raise awareness of the refuge with decision-makers in Washington, D.C.

“Any more development in the refuge at all will wipe us out,” Demientieff told me. “This is our health and our way of life that this administration is stomping all over.”

So far, according to Demientieff, the pleas of the Gwich’in have gone unaddressed in the halls of power.

“The refuge is now open for the first time in history, so they have ignored our concerns,” she said.

“They don’t seem to understand what we’re saying. For the Indigenous people in this country, oppression and genocide continue to this day. It’s 2018 and we’re still fighting for our human rights.”

Just two days earlier, the bi-annual Gwich’in Gathering wrapped up in Tsiigehtchic, N.W.T., where a declaration was signed reaffirming the Gwich’in commitment to protect the calving grounds.

“The first Gwich’in gathering in over 150 years was held in 1988, and that was when our elders and chiefs got together, because of drilling in the coastal plain,” explained Demientieff, “so now every two years, we come together and reaffirm our commitment. Our identity is not up for negotiation.”

Bernadette Demientieff, executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee in Fairbanks, Alaska. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

When our bush plane finally dropped us off at the Collins airstrip in the heart of the Brooks range mountains and then flew away, leaving us alone with our 70-pound backpacks and a startling silence, an adrenaline rush packed with both excitement and apprehension kicked in.

We were on our way, hiking over tundra and forging rivers.

As our journey stretched on, we used a satellite phone to connect with a research biologist from the Government of Yukon. We hoped some external insight could help us pinpoint the location of the herd.

The incoming news was bad: the herd’s usual post-calving aggregation in the foothills still hadn’t begun.

We needed temperatures on the coastal plain to warm up, prompting mosquitoes to drive the herd into the foothills and then the mountains in search of higher ground.

We had planned for months — done everything we could to give ourselves the best opportunity to see the herd on our planned 12-day journey — but the caribou still weren’t on the move up into the Brooks range mountains where we hoped to intercept them.

And so, we hiked, day after day.

Expedition members traverse open tundra north of the Collins airstrip in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, on day one of the trip. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

It was obvious, even in their absence, that this is caribou country: every patch of mud bore the tell-tale tracks of earlier caribou movement, and our group followed in millennia-old caribou trails weaving through tussocks and carved into shale-covered mountainsides.

When we finally received news on our last day that there were caribou nearby, our group was elated. We quickly mobilized for a day trek, taking just the barest of essentials.

A significant portion of the herd had been spotted heading toward us, 20 kilometres from our camp.

On terrain as rugged as this, we could expect that to make for a challenging six-hour hike. As we had to return to our same camp site at the Grassers airstrip beside the Hulahula, we were lucky to be able to pack light, but realized our day could end up being closer to a 40-kilometre round-trip saga — about the distance of a marathon.

After an extended river crossing, the team stopped to wring out wet socks and re-apply tape to blistered feet. Our group broke out the binoculars and took turns peering northward down the Hulahula valley, desperately scanning for any sign of caribou.

I mounted my longest lens and noticed hundreds of tiny brown ‘rocks’ that appeared to slowly crawl across the valley slope several kilometres away.

A feeling of jubilation washed over our group as the ever-growing spectre of failure evaporated: we were finally within sight of thousands of caribou, dotting the slopes of the valley across from us.

The herd was still over an hour’s hike away and we were also conscious of the fact that we had at least another six hours to go before getting back to camp.

Sitting atop a pingo, a type of ice-cored mountain unique to the Arctic, we consumed some of the very last calories of food packed for the trip, and planned our final push to bring us close enough to document the herd.

When our northernmost vantage point was finally reached, our view opened up upon what we estimated to be nearly 10,000 caribou.

Bulls pushed up slope toward rockier precipices, cows grazed and rested periodically, while calves sprinted about awkwardly, experimenting with their frisky legs beneath them.

Porcupine caribou cover the valley of the Hulahula river in the Brooks range mountains of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

A Porcupine caribou crosses a braided section of the Hulahula River. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

Caribou move along the banks of the Hulahula River. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

We had spent about two hours in the presence of the caribou and began to calculate how many hours of sleep we’d get after our long journey back.

We reluctantly packed up and headed out just as a light but steady rain began. A claustrophobic fog slowly settled over the valley.

What was already sure to be a challenging hike home became a cruel reminder that wild places like the refuge owe nobody safe passage.

The fog and rain grew heavier and our tiring team of 10 gradually began to spread out. With camp tantalizingly close, and believing navigation to be straightforward, one of our members forged ahead alone.

Just after 10 p.m. a few of us paused to scrape the bottom of our peanut butter jars and rehydrate in lieu of an actual dinner. Back on the trail, we came upon a creek that had risen to the point of raging thanks to several hours of rain.

It was immediately apparent that this obstacle would prove too much for a solo crossing — our minds turned to our friend who had pushed ahead of the group.

Had he attempted to pass and been swept down the river, it could be fatal. Searching for an alternate route, he could become lost in the unrelenting fog.

Back at camp, our fears were confirmed: our solo hiker had not arrived.

Forming a search party, pairs patrolled the edge of the river and adjacent valleys, where he may have ventured had he become disoriented.

One hour later, nothing. The night crept on. With the darkness and wet and fear settling into our bones, we hit hour two. Not a trace.

It wasn’t until after four in the morning that we’d finally reunite.

The lost team member was located back near that flooded creek, cold, wet and still searching in vain for a safe place to cross.

Rattled by this close call, our entire crew crashed hard just before 5 a.m. — just a scant few hours before our scheduled extraction flight.

We ultimately succeeded in our mission to see the caribou, but were also served a serious reminder of the harsh and unforgiving environment the caribou have to endure, even in the middle of summer.

Peering out over the sprawling grandeur of the refuge from the bush plane the next morning, I felt an exhausted mix of joy at having witnessed the caribou herd on their distant terrain and relief at our team having escaped that terrain intact.

Arctic fox remains atop a small pingo in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge serve as a reminder of the high stakes at play. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

For more than a decade Jeffrey Peter worked in Vuntut National park, tucked into northwest corner of the Yukon and separated from the wildlife refuge by no more than an imaginary international border.

Prior to this trip, he had never actually crossed over into the refuge. Now, having done so, he struggled to comprehend how the caribou can be so well protected on one side of the border, while their existence — and the existence of the Gwich’in nation across the north — is threatened by developments on the other.

“There are thousands of Canadian Gwich’in directly affected by this, and the herd spends a large part of the year in Canada,” he said. “If there is development in the calving grounds, we would see less and less caribou in Canada. They’re such an important part of the ecosystem and they have a big role to play on the Canadian side as well.”

Our group witnessed firsthand how something as minor as a few degrees temperature change, and something as small as a mosquito, can dictate when and where the herd will move.

And while our entire group took every precaution to not disturb the herd, we noticed how sensitive the caribou were to the presence of two-legged creatures, lurking with cameras in the shrubs a couple hundred metres away.

Having seen that, it seemed a stretch that oil and gas development in calving grounds would not have a significant effect on the herd.

Indeed, we have known for decades that human-caused disturbance on the landscape — roads, pipelines, drilling rigs and more — can have long-lasting impacts on caribou, even many kilometres away. It can cause individuals to lose weight, a devastating impact on a species that works endlessly to build fat reserves to survive the cold.

In just a few years in the late 1970s and through the 1980s, a surge of oil and gas activity near Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, redistributed the Western Arctic caribou herd on the landscape as they avoided roads and developments — even going to places where the food is less plentiful to avoid the disturbance — resulting in fewer calves.

The findings of scientists are in lockstep with the traditional knowledge and first-hand experience of the Gwich’in.

For Peter, the idea of brute industrial activity in the calving grounds is unthinkable.

“For all of human history, and predating that, it’s been unspoiled,” he said.

“To have this happen in our lifetime, and look back on it decades from now asking ‘how could we have let that happen?’ It just seems so irresponsible and short-sighted.”

Expedition members cross an alpine river in the Brooks Range mountains of the refuge. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

For the photographers on this particular trip, not seeing the caribou would have been a tremendous disappointment, but for Gwich’in the stakes are much higher.

For tens of thousands of years, Peter said, it’s been a matter of life and death whether they saw caribou.

“They had to really understand the movement of the herd and rely on traditional knowledge to allow them to survive,” he said.

“As Gwich’in, if there’s no more caribou, we lose our cultural identity, our connection to the land, to our ancestors. A lot of things get lost if the caribou don’t come back.”

The connection between the landscape, the caribou and the Gwichi’in spans multiple borders, ecoregions and hundreds of generations, and yet that seemingly robust relationship could be easily disrupted by subtle shifts in climate or a sudden re-arrangement of the political landscape.

With the Trump administration’s approval, seismic testing deploying 90,000-pound trucks with metal plates to shake the earth, could begin in the calving grounds as early as this winter.

The resolve of those determined to prevent this from happening has never been greater.

“Our culture’s been here for thousands of years — we’re not going anywhere,” Peter said. “This is our homeland. We want to continue to be healthy, happy people. To do that, we need caribou.”

Demientieff draws strength from the solidarity she sees across the border, and has faith that the final chapter of the Porcupine caribou has not been written.

“Our relatives in Canada are standing with us. We’re not going to back down. We’re not going to step aside. We’re going to continue to stand strong, in unity and in prayers, just as our elders directed us to. This fight is not over — far from it.”