Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

On a typical day in the sprawling Municipal District of Greenview No. 16, drilling rigs hum in the forest, pickup trucks slosh through muddy access roads and hydraulic fracturing shakes deep underground shale formations.

In the meantime, the municipal district spends tens of millions of dollars it receives in tax payments from oil and gas companies on projects across the region, making the district’s reliance on a single sector as strong as ever.

Infrastructure just outside Fox Creek, Alta. “The only reason we exist is to service the oil and gas industry,” the mayor of Fox Creek, Jim Hailes, told The Narwhal. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

In communities so deeply entrenched in oil and gas economies, the industry is not only a source of revenue, but of identity.

In 2018, the district — a large area of northwestern Alberta notable for its large swaths of trees and Crown land — received 58 payments in taxes and fees, totalling more than $77 million ($58.3 million USD) from oil and gas companies, according to data published under the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA), which came into force in Canada in 2015.

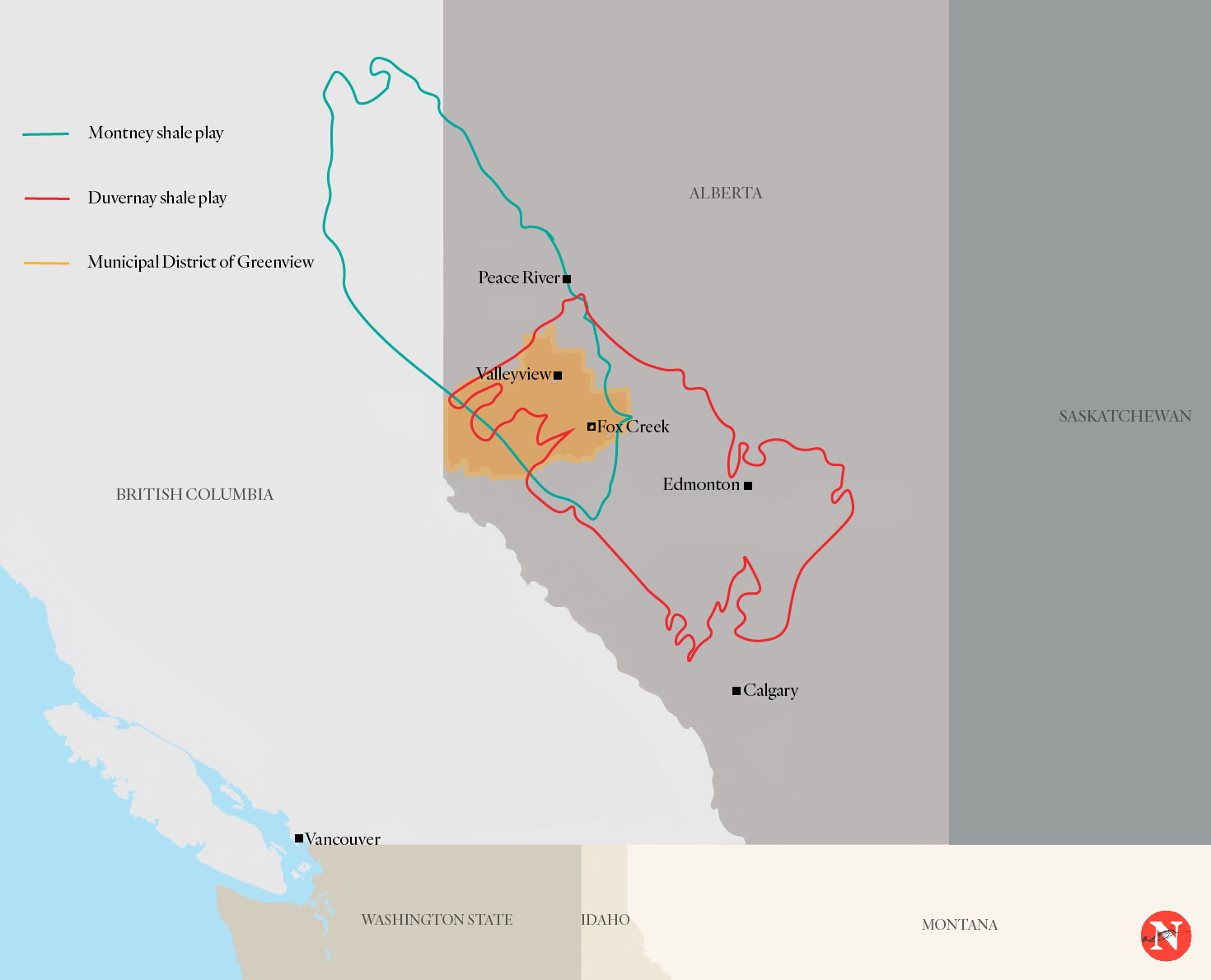

The Municipal District of Greenview is located within both the Montney and Duvernay shale plays, formations rich in natural gas. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Under the act, companies in the extractive sector must report payments made to all governments in Canada and across the world — a measure meant to “increase transparency and deter corruption.”

According to the 2018 data, the Municipal District of Greenview received more money in payments from oil and gas companies than any other county or municipal district in the province.

Just 5,583 people call the Municipal District of Greenview home (this includes only rural residents of the district, not people in the towns, which are governed separately), meaning per-capita payments from oil and gas companies equalled roughly $14,000 in 2018. This per-capita amount is approximately twice that of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, home to the oilsands — although Wood Buffalo (a different type of municipality that includes the city of Fort McMurray) received higher tax payments overall.

With figures like that, it’s not particularly surprising that support for the industry here isn’t waning, even as there are increasing calls around the world to decrease reliance on fossil fuels.

Last year, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres made headlines when he said the world is facing “a direct existential threat.”

“We need to rapidly shift away from our dependence on fossil fuels,” Guterres said, to prevent “runaway climate change.”

That sort of urgency isn’t felt by local officials in Greenview, where a fracking boom has brought much wealth to the region.

The Narwhal visited two of the largest communities in the region this summer to learn more about how the municipal district spends its oil and gas revenues, and what local officials envision for the future.

Dale Smith, the reeve of the municipal district, said the importance of oil and gas is “huge” in the area. “If we didn’t have oil and gas, and with the small farming base that we have …” he begins, trailing off as he thought about the implications.

Reeve Dale Smith in Valleyview, Alta., on July 24, 2018. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Vern Lymburner, the mayor of Valleyview — one of the larger towns in the district — finishes his thought for him. “These communities wouldn’t be here,” he said.

“Basically the reason these towns are here is because of oil and gas,” Lymburner told The Narwhal.

Mayor Vern Lymburner in Valleyview, Alta. Lymburner says the energy industry is the primary economic driver in the region, alongside some agriculture. “Basically the reason these towns are here is because of oil and gas,” he told The Narwhal. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Jim Hailes, a retired schoolteacher and the mayor of Fox Creek, echoed that sentiment when The Narwhal visited him later at his town office. “The only reason we exist is to service the oil and gas industry,” he said. “[The town] was artificially created 50 years ago.”

Mayor Jim Hailes in Fox Creek, Alta. “I’ve lived in Fox Creek for about 45 years,” Hailes told The Narwhal. “It’s a roller coaster.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The area surrounding Valleyview has a small amount of farming and forestry activity, but for both towns, oil and gas has long been the lifeblood of the economy.

“There are lots of different issues with regard to heavy reliance on a single sector,” John Parkins, a professor and department chair of resource economics and environmental sociology at the University of Alberta, told The Narwhal.

“One of the things we look at when a community is heavily reliant on a single sector is the potential for boom and bust economic conditions to really affect the fortunes and the sustainability of that community.”

Smaller communities, he said, often “lack the capacity” to absorb the shock of a big bust.

The Narwhal met with locals officials in the towns of Valleyview and Fox Creek — both geographically within the Municipal District of Greenview, though governed by town councils — to learn more about where exactly the millions in oil and gas revenues goes and how much the communities within the municipal district have come to rely on revenue from oil and gas companies.

The district collects revenue from oil and gas companies through taxes such as property taxes and taxes on machinery and equipment. According to Smith, the reeve, this revenue makes up “somewhere between, say, 95 and 97 per cent” of the district’s total revenue.

According to the district’s

financial statements, total expenses for 2018 were $89,868,181, meaning that the millions received from oil and gas companies are indeed a huge share of the money spent in the region — the $77 million the municipal district received in taxes and fees from oil and gas companies would make up more than 85 per cent of the district’s total expenses.

It’s clear oil and gas companies are paying far, far more money into local coffers than residents or other businesses.

Infrastructure from the oil and gas industry just outside Fox Creek, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The district uses that money for its own operational costs — like the maintenance of oil-and-gas service roads — and also shares it with surrounding towns through arrangements such as cost-sharing agreements.

“That money has allowed us to do projects we never would have had the ability to do,” Lymburner, the mayor of Valleyview, told The Narwhal.

In communities deeply entwined with the oil and gas industry, these payments are received with gratitude — and a deep appreciation not only of the enormous additions to local coffers, but to what is perceived as a generous and supportive industry.

“The [district] has been very, very, very, very, very generous,” Hailes, the mayor of Fox Creek, another small community south of Valleyview, told The Narwhal of the way oil and gas money is distributed.

“In a roundabout way,” Hailes said, “[oil companies] contribute to everything.”

Oil, Lymburner said, “has made us what we are.” Smith agrees. “Oil is ingrained in our society,” he said.

They don’t see that changing dramatically anytime soon.

Greenview is the third-largest municipal district in the province, covering an area of 32,989 square kilometres — larger than Belgium.

Outside of the towns — which have a combined population of approximately 3,800 people, according to 2016 census data — there are roughly 5,500 people living in the area. “This means there are over 6 square kilometres of land for every resident!” the district’s Facebook page boasts. Much of that land is used for industry — forestry or oil and gas.

A boom of activity, especially since the advent of directional drilling, in the Duvernay and Montney shale formations — large swaths of both of which are within the Municipal District of Greenview — has meant huge returns for the sparsely populated district.

The Duvernay formation has been a big deal in Alberta in recent years, not unlike the Bakken formation in North Dakota. The Duvernay lies under 130,000 square kilometres of the province — 20 per cent of Alberta’s total area. It’s been there for some 380 million years, formed during the Upper Devonian period when much of western Canada was under an inland sea.

Shale oil and shale gas are trapped deep within formations of shale — a form of sedimentary rock composed of compressed silt, clay and minerals. Trapped within the shale are deposits of oil and gas, often thousands of feet deep, that require what’s known as unconventional drilling — such as hydraulic fracturing — to access. Hydraulic fracturing involves sending water mixed with chemicals down into shale formations at high pressures to create cracks and allow trapped oil or gas to flow freely. Shale resources have become increasingly common in the global energy supply.

The National Energy Board estimates the Duvernay shale formation can produce a total of 542 million cubic metres of marketable crude oil, 2.17 trillion cubic metres of marketable gas and 995 million cubic metres of marketable natural gas liquids.

It is, as Alberta’s Energy Regulator put it in a 2016 report, “emerging as Alberta’s foremost unconventional shale resource.”

Jeff Rubin, former chief economist with CIBC World Markets, told The Narwhal that this potential means the region is better poised for future economic growth than Alberta’s oilsands.

“There’s a lot stronger world demand for that resource than there is for Alberta bitumen,” he said, pointing to increasing world demand for shale gas.

“Decarbonization, if that occurs — and by that we mean stabilization and ultimate reduction of carbon emissions — involves the large-scale substitution of shale gas for coal,” Rubin told The Narwhal. Rubin noted that he believes the production and profitability of liquefied natural gas in the area would be heavily dependent on pipeline access, such as the Coastal GasLink pipeline in B.C.

But even an increasing popularity of shale gas worldwide doesn’t buffer the region from downturns, Rubin cautions.

“Any dependence of that nature on a resource base — oil, copper, nickel, whatever — comes with it the cyclical nature of the business cycle,” he said.

“Boom and bust: that’s true of any commodity market.”

A campground where workers live year round in Fox Creek, Alta. Economist Jeff Rubin says that while the region is better poised for future growth than the oilsands, it still needs to be prepared for ups and downs. “Boom and bust: that’s true of any commodity market,” he said. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Accessing the riches beneath the surface isn’t without consequences.

Hydraulic fracturing uses large amounts of fresh water — water that is injected deep into the ground in the place of the oil or gas that is being drilled, where most of it will remain forever.

Then there are the earthquakes. A study published in the journal Science last year noted “a sharp increase in the frequency of earthquakes near Fox Creek, Alta., began in December 2013 in response to hydraulic fracturing.”

Concerns have also been raised in recent years about the implications of methane — a potent greenhouse gas commonly leaked or intentionally flared in natural gas production. A study published earlier this year in the journal Biogeosciences posited that methane from shale gas — often accessed through hydraulic fracturing — may have bigger implications for the climate than previously thought.

“Shale-gas production in North America over the past decade may have contributed more than half of all of the increased emissions from fossil fuels globally and approximately one-third of the total increased emissions from all sources globally over the past decade,” the authors of the study wrote.

But this hasn’t slowed down drilling in the area.

Part of the importance of the Duvernay lies in its richness in natural gas liquids, including condensate — a liquid that can be combined with bitumen from the oilsands to ease transport through pipelines.

“Shale is by no means an environmentally benign process,” Rubin said. But local officials see an industry striving to make improvements in its footprint and view any consequences as outweighed by the economic benefits for the region.

It’s clear that oil and gas money has built much of these towns.

Lymburner takes us on a tour of the Greenview regional multiplex — an obvious feather in his cap as mayor of Valleyview.

The Greenview Multiplex in Valleyview, Alta. The Municipal District of Greenview paid 83 per cent of the costs to build the facility, thanks in large part to tax payments paid by oil and gas companies. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A farmer donated the land where the massive building now sits, just on the periphery of the town. The district paid for 83 per cent of it, as well as 80 per cent of the operating costs — thanks in large part to revenue from oil and gas companies.

From the foyer, we can see the pool, the waterslide and the lazy river. There’s a full gym upstairs, as well as dance studios, party rooms and racquetball courts. The receptionist tells us between 250 and 300 people visit per day.

The Greenview Multiplex in Valleyview, Alta. The facility includes a pool, a lazy river, a full-service gym, dance studios and racquetball courts. “It’s hard to believe,” Mayor Lymburner said of the facility in a town of fewer than 2,000 people. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Lymburner looks around, obviously proud. “A town of 2,000 people has this,” he says.

“It’s hard to believe.”

We also hear about new Stars Air Ambulance landing pads, a new medical clinic, new playgrounds, money for the seniors’ centre, money for the school — the list goes on.

In Fox Creek, the local peace officer was waiting for a shipment of kids’ bicycle helmets to arrive — he’d be handing them out for free to kids riding without one. They were paid for by Shell.

“The oil and gas people are so generous it’s ridiculous,” Hailes said when we visited him in Fox Creek. “The school doesn’t know what to do with it all.”

Mayor Jim Hailes in the new multiplex in Fox Creek, Alta. “The [district] has been very, very, very, very, very generous,” Hailes told The Narwhal of the way oil and gas money is distributed. The Municipal District, which receives large tax payments from oil and gas companies, was a large contributor to the building of his town’s multiplex. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

According to a 2018 report from the Parkland Institute, the Big Five together brought in $46.6 billion in aggregate profits in 2017 — roughly equivalent to the total income of the Alberta government that same year.

When Hailes takes us on a tour of his town’s new multiplex — our second such tour in one day in the district — he’s proud of the arrangements created with oil and gas companies.

In exchange for having their names emblazoned on parts of the multiplex — the bleachers, the pool, the centre of the basketball court — the companies will pay maintenance costs for part of the facility. Otherwise, such big upkeep expenses could spell trouble for such a small town.

The Fox Creek Greenview Multiplex in Fox Creek, Alta. In exchange for having their names emblazoned on parts of the multiplex energy companies will pay maintenance costs for part of the facility. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Parkins, the sociologist, points out that it’s important for communities to think long term when they decide where to spend their money.

“Is it actually a good thing that the local oil and gas industry pumps tons of money into the recreation centre and pays for the local school or the local sports teams to buy jerseys and whatnot?” he wonders.

“Or would it be more effective for the municipality to use those funds to promote economic diversification through initiatives like entrepreneurship training — small business development, incubating small businesses, providing training for people who want to foster new growth within the region?”

The Fox Creek Greenview Multiplex in Fox Creek, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Parkins points to Pincher Creek as an example of a town that saw the “writing on the wall.”

Twenty years ago, the region was heavily reliant on a local gas plant they knew wouldn’t last forever, he said. The community made a big push for wind power, which is now a huge industry in the area. In 1993, one of the first commercial wind farms was built on Cowley Ridge in the Pincher Creek region.

“Communities in Alberta are looking at the future and trying to anticipate what the future of the resource is going to be,” Parkins said.

Parkins points to towns like Fernie or Lacombe that have re-invented themselves in recent years, having transitioned to more diverse economies less reliant on a single resource sector — creating new jobs for residents in the process.

“It might take a lot longer for places like Fox Creek to make that kind of transition,” he said, citing the difficulties of being further away from major population centres or tourist destinations.

Oilfield rentals in Fox Creek, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Smith, Lymburner and Hailes all feel the importance of the success of the oil and gas industry viscerally — all three have adult children working in it.

I asked the local officials whether they’re concerned so much of the district’s revenue relies on oil and gas revenue, with a relatively small tax base. “I think we’re probably always concerned, Lymburner said. “You don’t want to be a one-horse town.”

Mayor Vern Lymburner in Valleyview, Alta. Lymburner told The Narwhal the region is using money from oil and gas companies to try “to create economic development.” He says facilities like the multiplex help keep people in the town. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Smith agrees, and said that’s part of the boon of receiving revenue from oil and gas — to try to create some stability outside of the industry. “We’re trying to create economic development,” he said.

Town planning documents, noting that the oil and gas industry “may be affected by global economic forces and environmental concerns,” also contain diversification goals and point to a future in which the Valleyview area may “diversify towards renewables, drawing on closely related existing expertise.” The documents also highlight the importance of other industries in the area: agriculture, forestry and sand and gravel extraction.

“It’s a major focus for us, so that it’s not strictly oil and gas, or so we can funnel some of this money into creating other opportunities,” Smith said.

Hailes, the mayor in Fox Creek, put it another way.

“I’ve lived in Fox Creek for about 45 years,” he said. “It’s a roller coaster.”

When times are tough, the mentality, he said, is “please God give me another oil boom and I promise not to piss it away again.” He chuckles. That’s not the best way to go about it, he implies with a grin.

Parkins points out the difficulties of diversifying.

“One of the concerns about single-industry towns is that they tend to be over-adapted to a single industry, so the entire workforce and the entire human resources that exist there, are oriented or adapted to a single industry,” Parkins told The Narwhal.

“As a result, it’s quite challenging for the human capital — the people who live and work in those communities — to transition to other sectors because of the kinds of skill sets that are adapted to, in this case, oil and gas, that are not necessarily transferable to another sector.”

A pick-up truck parked outside a restaurant in Fox Creek, Alta. In communities deeply entrenched in oil and gas economies, the industry is not only a source of revenue, but of identity. “Oil is ingrained in our society,” the reeve of the district told The Narwhal. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Local officials acknowledge the difficulties, too.

“It’s a huge industry for Alberta. It’s never going to last forever, there’s only so much of it there. So yeah, at some point in time, you gotta have a plan,” Smith said.

Part of the plan is to make the towns more attractive to potential residents, to build a stable community in case the future isn’t always so flush with cash.

“This enhances your ability to bring people to your community,” Lymburner said. “It helps you get doctors, it helps you to retain people.”

People working out on a rainy day in the Greenview Multiplex in Valleyview, Alta. “This enhances your ability to bring people to your community,” Lymburner said. “It helps you get doctors, it helps you to retain people.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The revenue doesn’t come without drawbacks, though the enthusiastic support of the industry makes them more than palatable to the officials we spoke with.

In recent months, communities across the province have started to voice complaints about failing to receive money they’re owed from oil and gas companies.

The district’s financial statements acknowledge the risk of not being able to collect taxes. “Greenview is exposed to the credit risk associated with fluctuations in the oil and gas industry,” the statement reads. “A significant portion of the property taxes outstanding … are receivable from companies in the oil and gas industry.”

In July, for example, the Greenview council heard that Seven Generations Energy Ltd., a natural gas producer, had requested that the district reverse finance charges of $120,178.27 owed. Another Calgary-headquartered company, AlphaBow, owed $131,739.07 in outstanding taxes.

“It’s not a perfect world,” Smith said. “Smaller gas companies are struggling to pay their bills.”

But overall, Smith said, the district has not had huge issues with companies struggling to pay.

Oil and gas infrastructure just outside Fox Creek, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Where the concerns lie are more far-off, and more abstract: what will the community look like in 10 or 20 years? Can it sustain a major bust?

“These are really intractable challenges,” Parkins said. “When we look at more remote communities where their options are more limited, it’s not easy to see a path towards economic diversification.”

“But it’s possible to move the needle a bit, and to anticipate and be reflective about the future and anticipate that fracking is not going to be here forever.”

There are signs of promising economic diversification on the horizon. In August, Alberta’s first commercial scale geothermal facility was announced for a location just south of Grande Prairie. The Greenview Geothermal Power Project will produce enough electricity to power 6,800 homes. Drilling and construction partner PCL Construction says the project will create 1,000 jobs.

“We know how to drill in this province, and we know how to build effective, large-scale power facilities. We have world-leading expertise in those areas, because oil has played such a huge part in our economy for so long, and we need that same expertise to create geothermal wells,” Sean Collins, president of project leader Terrapin Geothermics, said. “Projects like this are diversifying from our strengths, and Canada’s strength lies in our energy sector.”

The town of Valleyview has another new building to show off to visitors: its town office. Compared to its predecessor — a small, one-storey, nondescript brick building with weathered red awnings and crumbling concrete steps — the new building is extremely modern, and much bigger.

The Town of Valleyview’s new “net-zero” office. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

It’s a big deal in Valleyview, and not only for its design caché. The town decided to build a net-zero building — the first commercial building of its specifications in the world.

The new building features passive-building designs and produces its own electricity. It has 78 solar panels installed on its roof, and just opened last year.

I asked Lymburner why the town decided to go ahead with a net-zero building.

His answer was simple.

“It’s the future.”

In the municipal district of Greenview, that kind of future feels both far off and, at times, just around the corner.

This article is part of a collaboration between The Narwhal, the Corporate Mapping Project, Publish What You Pay Canada and the Natural Resource Governance Institute. The Corporate Mapping Project is jointly led by the University of Victoria, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and Parkland Institute. This research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Update Monday, September 23: This article was updated to reflect that Jeff Rubin is no longer a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...