Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

This photo essay is part of The Narwhal’s BIPOC Photojournalism Fellowship, operated in partnership with Room Up Front and made possible by The Reader’s Digest Foundation and the generosity of The Narwhal’s readers.

Canada brandishes its agricultural sector as an economic “powerhouse” that’s responsible for producing some of the world’s highest quality foods.

In 2019, the federal government unveiled the first-ever Food Policy of Canada, which is meant, in part, to ensure everyone across the country has access to “a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious and culturally diverse food.”

Yet the food that is harvested in Canada often does not end up on the plates of racialized and marginalized communities. Individuals from the Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) community represent the most food-insecure people in Canada.

According to research from PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research, an initiative of the University of Toronto in partnership with other universities, national food insecurity — the inability to access food due to financial constraints — is predominantly experienced by Black and Indigenous communities.

A 2020 PROOF analysis of Stats Canada data from 2017 and 2018 found that 28.2 per cent of Indigenous households and 28.9 per cent of Black households identify as being food-insecure, representing the highest rates in the country.

Black-centred urban farms in Toronto — one of the world’s most diverse cities, and Canada’s largest metropolitan city — recognize this issue and see first-hand how it impacts their own community.

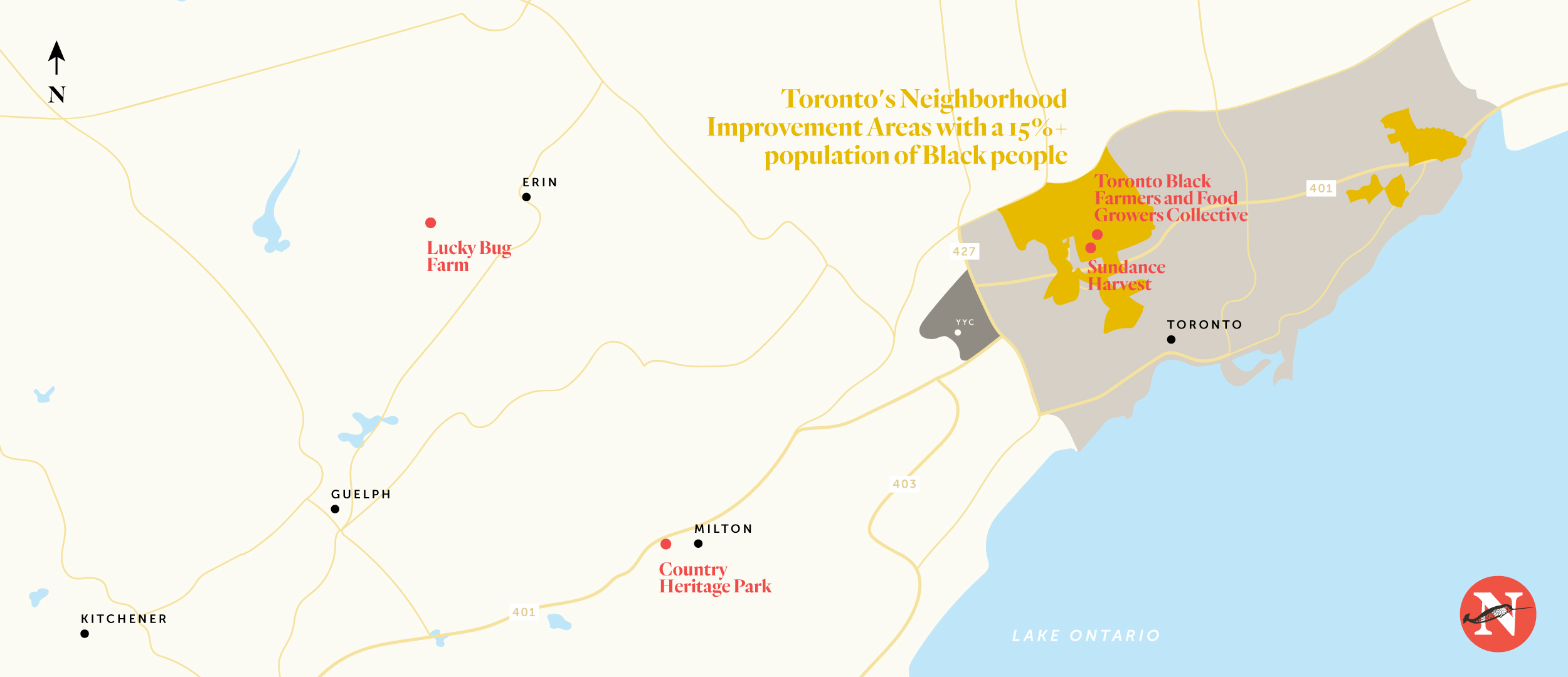

Toronto’s primarily Black neighbourhoods — such as Downsview-Roding CFB, Weston and Glenfield Jane Heights — are some of the poorest in the city. In 2014, the city identified these neighbourhoods — along with 28 others — as Neighbourhood Improvement Areas. Today, these neighbourhoods have been hit the hardest with COVID-19 cases.

But even as an urgent need to improve these areas is top-of-mind for Toronto decision-makers, Black urban farmers say they still face significant uphill battles when it comes to bringing healthy, local produce to Black urban communities.

“Your food is your medicine and your lifestyle is your therapy,” Jacqueline Dwyer, co-founder of the Toronto Black Farmers and Food Growers’ Collective, tells The Narwhal. “I don’t see our food doing that. [Black people] are eating the worst kind of food now.”

Dwyer says there’s been a concerted effort from Black farmers in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) to bring more produce to the communities that need it most.

“We’re not here to sell to sexy white markets. We’re here to serve our community, to feed those who don’t have the money to buy food and access food banks regularly.”

The city recognizes this issue too, and initiated the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy 2020 to provide funding to the neighbourhood improvement areas and establish action plans to improve their wellbeing. Providing “free land, soil, mulch, etc. for community gardens and urban farming,” was listed as a prioritized action to promote food security for the improvement ares.

Yet, despite these ongoing initiatives, Black farmers in the city say not enough is being done to connect food-growers with useable land. Accessing and retaining arable land — that is both affordable and offers proper infrastructure — continues to be a struggle for these marginalized farmers.

The following photos document the experience of three Black-led farms, Sundance Harvest, the Toronto Black Farmers and Food Growers’ Collective and Lucky Bug Farm, which are committed to resolving food insecurity within their communities but are struggling to access and retain the necessary land. Two of the farms are based in the GTA and one is based in Wellington County. Each of them, while different, have unique experiences with land accessibility and retention.

Sundance Harvest is a for-profit farm, founded and run by 24-year-old Cheyenne Sundance. The farm is located at Downsview Park, an urban federally and provincially run greenspace about a twelve-minute drive from the intersection of Jane and Finch that once served as a Canadian Forces Base.

Sundance became interested in farming after she left the suburb where she grew up and began travelling. At 18-years-old, Sundance says her visit to a farm in Viñales, Cuba, piqued her interest. She admired the way the farm served its community.

After her travels, Sundance made her way back to the GTA, intent on finding a job within the agriculture industry. But she says she couldn’t find a farm that paid their workers fairly. Nor could she find a farm that would advocate for food justice.

“That’s organic farming [in Canada]: white men saying ‘you can live in a tent, work 40 hours a week and we’ll give you lentil soup and rye bread,’” she says.

“I didn’t want that life.”

And so, Sundance started her own farm with the eponymous name, using her life savings and a $5,000 grant from a non-profit group.

“I wanted to start a farm because I wanted to see a farm like this,” she says.

By “this,” Sundance means a farm that is Black-led and focuses on food justice by serving marginalized folks with their produce and mentorship programs, all while paying workers a liveable wage.

As a young, Black woman who came from a lower-income family, Sundance knew creating a farm wouldn’t be easy, especially when it came to finding land. But she was willing to improvise.

In 2019, when she noticed an empty greenhouse at Downsview Park, Sundance approached the people on site but couldn’t find an answer on who to talk to about renting space to start her own farm. With a little internet sleuthing, Sundance found out that Canada Lands Company, a federal Crown corporation that manages land and develops former Government of Canada properties, was leasing the space and immediately emailed them to inquire about rent.

“I don’t like waiting, and I’m not patient. So I just did it,” she says. “Everyone says farming requires patience. It should but — at the same time — if you want to make fast decisions and grow fast, impatience is nice.”

Sundance’s quick request met with a favourable response. She heard back that, to start, she could rent half a greenhouse from Canada Lands Company. Around a year later, in September 2020, she expanded to one full greenhouse. By December that year, she expanded to two greenhouses and a one-third acre parcel of land.

Sundance says she was able to make profit within the first year of farming. She sells more than 100 pounds of tomatoes — one of her farm’s specialties — every week.

And her success has gone beyond just what she’s grown in the dirt. Over the last year Sundance has garnered media attention across Canada for her work in food insecurity, food justice and food sovereignty. Her Instagram has also increased by tenfold, with nearly 32,000 followers to date.

Media coverage of Sundance Harvest’s success resulted in a new realm of possibilities for Sundance. She says as her farm’s popularity grew, real estate developers began reaching out to offer their undeveloped land for farm space — for free.

“[They’re] reaching out to me to start farms where a condo would be. I would have the land for five years before they would start building. I was offered an acre with no rent because they wanted to use the Sundance branding. If I was someone who had no following, they wouldn’t do that.”

Sundance says she still faces barriers when working on site at Downsview Park, in spite of her success and being established for nearly two years.

“The amount of sexism and racism I experience here from the public is crazy,” she says.

Sundance and her staff — particularly the staff who are young women of colour — have experienced white men harassing them, following them to the greenhouses, or standing and staring at them for long periods of time.

“They’d keep asking: ‘Why aren’t you talking to me? Why aren’t you showing me this? What are you doing with the garlic?’” she recalls. “I pay a lease here. I’m not paid to teach you. I have to work to make money.”

Sundance eventually introduced walkie talkies for staff and instituted new rules about the company having at least two people on site to ensure employee safety.

“And if that doesn’t work, I always have a harvest knife on me in case,” she says.

Sometimes, Sundance says, the sexism takes a more obvious form.

“My friend Evan was doing the drip tape irrigation the other day. I was very clearly telling him what to do. This man comes up, steps in front of me and starts talking to Evan, offering his company’s packing and delivery services to the farm.”

Theft has also occurred at the site, with nearly 100 garlic pods being stolen in July. Sundance says she is currently trying to build more fences and tape, and move certain plants to the greenhouse as methods to prevent further theft.

Experiences like these are also why Sundance wants to mentor young marginalized folks through her 12-week program, Growing In The Margins. This includes people who identify as low-income, Black, Indigenous, a Person of Colour, LGBTQ2S or a person with a disability. The mentorship stream of this program aims to educate those who want to start their own full-time career in urban farming.

Lucky Bug Farm was established in 2020, thanks to the help from Sundance Harvest’s mentorship program. Founder and owner Aliyah Fraser originally had an urban planning career, working at a law firm and with various levels of government. She says the lack of focus on sustainability and marginalized communities that she witnessed during her career made her want to switch professions.

“[I realized that] at the end of the day, the people who have the power to make changes in our communities are not interested in making those changes. They’re interested in profits,” she says. “It’s hard for me to feel engaged in it.”

Yet she still wanted to put the knowledge and skills she had gained to good use.

“I remember thinking: what do I love? One of them is food and the other is the environment. Farming kind of sits at that intersection,” Fraser says.

“At the same time, I wanted to do something that involved working outside, doing things that were kind of different every day. And something about working with the land called me.”

She says that when she happened upon Sundance’s work around May 2020, “it felt like serendipity.”

“I was trying to find someone who was kind of doing what I was thinking in my head, trying to find a precedent … [of] Black-owned urban farms in Canada,” Fraser says.

Sundance and Fraser had a one-hour consultation that summer. It was during that time when Sundance encouraged Fraser to apply for Growing In The Margins. Fraser says the mentorship program solidified her decision to switch to farming as a full-time career.

“It was like unlocking a different level of my brain,” she says about the program. “The space that Cheyenne created was so informative. It’s a space full of hope and imagining possibilities for how things could be different.”

As a first-time farmer, Fraser says it’s the “lack of access to land that is [her] own” that is impacting her right now. “I think that speaks historically to the ways that Black people have been shutout [from] ownership in this country.”

Fraser, who’s been living in the Kitchener-Waterloo region since attending University of Waterloo, was ideally hoping to find arable land with the right infrastructure near her. Instead — with the help of Sundance — she was able to find land in Wellington County, near Erin, Ontario. She says the commute is about 45 minutes by car from her place.

Fraser is renting a quarter of an acre of land at Zocalo Organics, a farm that runs an incubator that prioritizes land accessibility for BIPOC farmers.

“It’s like, pretty small in farming terms. But it’s also over 11,000 square feet,” Fraser says. “Starting with a quarter of an acre seems manageable.”

Still, Fraser says it shouldn’t be this difficult for people of colour to find land like this. She wants all levels of government to step up and “make some decisions about the type of agriculture they’d like to see.”

“In my opinion that should look diverse and inclusive, not only for Black people, but for Indigenous people and other people of colour,” she says.

The Toronto Black Farmers and Food Growers’ Collective was established in 2013, also at Downsview Park. At the time, it was one of the first Black-led park farms in Canada.

“We set up about a 2.5-acre farm,” Dwyer says. “[Eventually], people figured out what we were doing. People who would use the park on a regular basis would protect the farm when we weren’t there.”

The Collective had their last harvest at that 2.5-acre space in 2015.

“We were told by Downsview Park that we couldn’t go back over there in 2016. At the time, they started putting in the infrastructure to build that community of condominium townhouses over there,” Dwyer says.

Dwyer says she and her partner, Noel Livingston, didn’t object at the time, as they were still new to the farming community in Toronto. Eventually they partnered with Fresh City Farms, which was established in 2011, and were relocated to the land that they are at today.

Dwyer says Fresh City Farms recently signed a long-term lease with the Canada Lands Company, where they will receive an 11-acre plot at the south east area of Downsview Park for up to 20 years. According to their website, Fresh City Farms is currently looking for partnerships, as they say they will be using 1.5 acres of the land, while the rest will be shared by partners.

They estimate that the monthly operating costs per half-acre to be between $750 to $1,100, which Dwyer says is unaffordable for the Black community and other marginalized groups.

“…We don’t have money,” Dwyer says.

In May 2021 Fresh City Farms commented on the matter in an Instagram post after someone voiced a similar concern on not bringing the collective with them to their future location, as well as their steep operating costs. Fresh City’s reasoning for the $750 to $1,100 operating costs was not to profit off the land. They say that the costs — which include rent, property taxes, insurance, electricity, water, repairs, washroom cleaning and garbage removal — have continued to be a “great challenge” at their site, as the costs are not paid by their landlord, Canada Lands Company. As a result, the operating costs will be split by their prospective partners.

“[However] we will do everything within our power to ensure that cost is not a barrier to accessing the land, including finding donors, supporting partner grant applications and helping to coordinate a fundraiser,” they wrote.

“It’s very tragic to see,” Dwyer says. “The people who work [at Downsview] predominantly are not from these neighbourhoods. They live in a 905 region or they drive into Toronto. So all this money that has been given to empower a neighbourhood or a community of neighbourhoods is really not doing that.”

With a reduced amount of arable land that includes proper infrastructure and more people to feed, Dwyer and Livingston say it has been impossible to find ideal land for farming in Toronto.

“We are left out of getting adequate resources to have a good operating team of people to do this work,” Dwyer says. “We’re locked out of infrastructure money, so we can’t put down our greenhouse and create our own space for our food hub.”

As a result they have created a partnership at Country Heritage Park in Milton, where they have access to two acres of land. The private land is about an hour-long commute by car from Downsview Park.

“They were kind enough to give us this land,” Dwyer says in regards to the members of Country Heritage Park. “I see the people here actually live like a community. Here, they support each other. They’re still some good people left. When we come together, we can solve our issues.”

For Dwyer and Livingston, this partnership has been tension-free. Here, they are able to do most of their harvesting, as well as provide and lease plots to community members and organizations who want to harvest their own crops.

Dwyer also wants more to be done in the agricultural system in Canada, especially considering the history.

“[Colonizers] didn’t bring slaves here to pay them a fair wage. This agricultural system was built off the back of slaves and I am here unequivocally to tell them that I want reparation,” she says. “I want reparations for my daughter, myself, my mother, my grandmother, my great grandmother and my great-great grandmother. Genocide has been happening ever since you met us. And now we’re saying enough is enough.”

“We need to now sit in communities and develop our own plan where we can actually share resources,” she says. “We need more feeding programs. We need to see some of our parks — that have good land — be rezoned to put our urban farms and help feed our number of communities.”