Alberta oil and gas companies could avoid cleanup costs by installing solar panels: government report

An Alberta government-commissioned report suggests oil and gas site companies may be able to install...

This is not how Rhonda Kirby thought she’d be spending her retirement.

The former elementary school teacher was always conservation-minded, sure. And she was always outdoorsy — she and her husband, Tom, love snowshoeing, hiking and riding all-terrain vehicles on a swath of wetlands and forest by their home in The North Shore, Ont., about halfway between Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury. Then she found out a quarry was proposed to go in on that land, and that it’s also home to a rare but thriving population of threatened Blanding’s turtles. That just didn’t seem right.

Suddenly, she was diving into turtle conservation, trying her best to understand the laws governing quarries and playing host to scientists who used her home as a staging area for wetland research. For over six years now, Kirby has worked to oppose a type of project that almost always receives a green light in Ontario.

“It has been a constant chase,” Kirby said, standing at a wetland’s edge in early September, blue jays calling from the treetops above. “If the best we can hope for is that we pissed them off, then I guess that’s what we have [done]. But that won’t be enough.”

Kirby and her allies in the grassroots group Advocates For The North Shore Water and Environmental Resources — a coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous quarry opponents, who she calls a “bunch of northern hicks” that their opponents greatly underestimated — argue the project isn’t necessary. The region is already dotted with pits and quarries that produce aggregate, the rocks and sand used in concrete, they point out.

Darien Aggregates, the company proposing the quarry, and its majority owner, Rankin Construction, contend this site is unique. If approved by the Ontario government, it would produce trap rock, a harder-to-find substance good for highway construction as vehicles are less likely to skid on it than other paving materials. Rankin Construction CEO Tom Rankin declined to answer specific questions from The Narwhal, but said in an email the company has worked to be sustainable and improve the environment.

Rankin Construction has also said the project will create up to 25 jobs in the community, which had a population of less than 500 people as of the 2016 census.

“There’s a sense of complacency, I think, in northern Ontario, because there’s so much of this,” Kirby said, gesturing to the foliage that was just beginning to turn red and water glittering in the sunshine.

“They don’t realize that’s what happened in southern Ontario. They started hacking away at it a little bit at a time.”

Tom, her husband, nodded as she spoke. “One bite at a time,” he added. “But eventually, you’re gonna run out.”

Versions of this dispute are playing out all over Ontario, in the many communities where new quarries are proposed.

The aggregate they produce feeds the growing province’s appetite for concrete to build homes and roads. One kilometre of six-lane highway requires about 2,590 truckloads of aggregate, according to the Ontario Stone, Sand and Gravel Association, a group representing industry. And although some developments spark controversy, others are aimed at improving safety, particularly on remote northern roads.

“How will we welcome and accommodate four million more people in our province in 20 years if we cut off the bottom of the supply chain that builds that infrastructure?” Norm Cheesman, the association’s executive director, wrote in 2022.

Opponents argue Ontario doesn’t need any more quarries, and the environmental impact of extracting aggregate is too great a cost. Aside from disrupting habitats, aggregate extraction also provides the raw materials for highways and urban sprawl that contribute to climate change. The Reform Gravel Mining Coalition, an alliance of environmental groups that includes the one Kirby leads, has argued for a moratorium on new quarries and pits, saying the province has licensed companies to extract 13 times more than the amount of aggregate it actually uses every year.

In some cases, like the one playing out in The North Shore, quarry applications also impact places important to Indigenous communities.

The Ontario government is currently reviewing the North Shore project, with ministries looking at Darien Aggregate’s application to extract aggregate and mulling whether a permit to damage endangered species habitat might be needed. Meanwhile, the province has overhauled environmental policy again and again over the past four years, constantly shifting the playing field for people like Kirby.

The Darien Aggregates quarry, if built, would be just north of Lauzon Lake, a haven of cottages, docks and dense trees. Kirby’s home is tucked alongside the lake, at the end of a road leading from the Trans-Canada Highway. Where that road ends, a rugged trail begins, winding up to the proposed quarry site on what the government has designated as Crown land.

Eventually, the thick brush and rocky outcrops of the Canadian Shield along the path give way to a vast series of connected wetlands, with grasses waving and water rippling in the breeze. Though no tiny reptile heads were visible in early September, when nights were beginning to get cold, this particular wetland is a hotspot for slowpokes with shells.

A few types of turtles hang out here, like at-risk snapping turtles and painted turtles. But endangered Blanding’s turtles have captured a lot of the spotlight, because there are an awful lot of them. Conservation biologist Gabriella Zagorski studied the turtles in 2017 and 2018 as she worked on her master’s thesis at Laurentian University. She found among the highest known density of Blanding’s turtles ever reported — though northern Ontario is speckled with similar wetlands that haven’t been studied, and even denser populations could be out there.

The larger point of the research, Zagorski said, was to look at how species at risk legislation is actually working in practice. “When we discover one of the densest sites for Blanding’s turtles in Ontario that we know of and nothing is done, how is that legislation working to help us in these situations?”

Zagorski’s team captured 56 Blanding’s turtles in and around the proposed quarry site, using Kirby’s house as their basecamp. Turtle catching is easy work in the spring, when animals are still waking up from a winter spent hibernating underwater, but in the summertime, it’s an exercise in patience. Zagorski would don hip waders and slip into the wetlands, her chin just dipping underwater as she inched painstakingly towards each specimen. The method earned her the nickname “turtle whisperer.”

The team attached radio transmitters to each turtle they caught, to see how each one moved around the wetlands. Some chunks of the quarry footprint are categorized as “critical habitat” for the turtles, meaning it’s crucial for the survival or recovery of the species. Other areas are less critical but still important, like travel corridors: turtles retrace the same paths year after year as they move from wetlands to nesting sites to the spots where they spend the winter, and get disoriented if those corridors are disrupted.

A consultant for Darien Aggregates has proposed creating “ecopassages” that could help the turtles pass under quarry roads that would disrupt these travel corridors. That would help, but “reptiles may become stressed when trying to find the entrance to ecopassages, exposing themselves to higher risk of injury or predation,” Zagorski’s study noted.

Blanding’s turtles are marked by their yellow throats and chins and their slightly upturned mouths, which often look like a grin. They can live to the wizened old age of 75. The turtles can cross large distances, sometimes travelling hundreds of metres or even a few kilometres away from the wetlands they live in.

In Ontario, Blanding’s turtles mostly live in the Great Lakes basin. One of the biggest threats to their survival is the destruction of their habitat, which the provincial government knows, having said so in its policy statement about protecting the species in 2020.

To Anishinaabe people, or Anishinaabeg, turtles are calendars: markings on their shells correspond to the number of lunar months in a year and the number of days in a lunar month.

“Those turtles are very sacred,” said Nookimis Marly Day, who comes from Serpent River First Nation, a stone’s throw from the proposed quarry site, and now lives in Baawating, or Sault Ste. Marie. Day is working with Advocates For The North Shore Water and Environmental Resources to fight the quarry proposal. “The more I heard about these turtles, I had a real concern because animals are equal to humans.”

Other species at risk live around the proposed quarry site, too — like myotis bats, and whip-poor-wills, an elusive bird named after the call it sings on summer nights. Moose also feed at the wetlands. They’re not endangered in Ontario, but the species is on the decline.

Quarries and the ways they can change a community are nothing new on the north shore of Lake Huron. For a long time, companies have extracted crushed stone and gravel from the rock of the Canadian Shield. People driving by can see a few aggregate operations just off the Trans-Canada Highway, but a provincial mapping tool shows there are dozens more between Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury.

There’s a long history of resource extraction here, too, one that feeds into why some communities along the north shore are worried.

Beginning in the mid 1800s, Canada claimed authority over the north shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron — Anishinaabeg territory — and began issuing licences to extract it, without a treaty.

Anishinaabe leaders had asked for years for a treaty, even travelling to Montreal in 1849 to address the governor general. “Can you lay claim to our land?” chiefs asked the governor general. “If so, by what right? Have you conquered it from us? You have not; for when you first came among us your children were few and weak, and the war cry of the Ojibway struck terror to the heart of the pale face. But you came not as an enemy, you visited us in the character of a friend.”

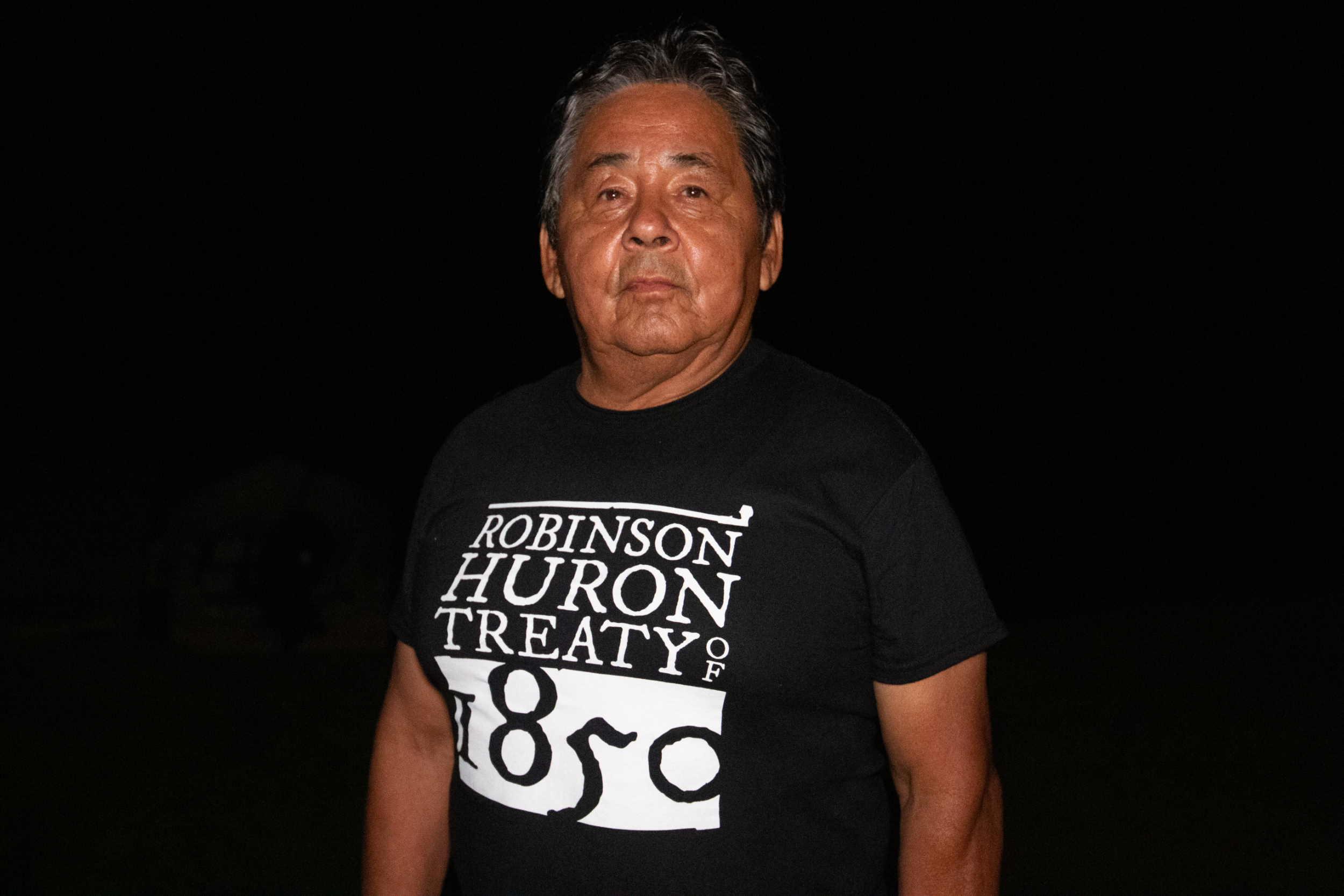

Later that year, Anishinaabeg seized and shut down a mine near Lake Superior, forcing the government to come to the table. In the end, two treaties were signed — one covering the north shore of Lake Huron, the 1850 Robinson-Huron Treaty.

The Anishinaabeg who signed the treaty didn’t surrender their land. They agreed to share it, in exchange for an annual payment that was supposed to increase alongside resource extraction revenues. But the government broke that promise, refusing to raise it beyond $4 per person since 1874. Ontario courts have sided with 21 First Nations who have filed a lawsuit over the annuity, saying it needs to be re-negotiated. The Ontario government is currently appealing those decisions to Canada’s Supreme Court even as it negotiates with the First Nations.

In the 172 years since the treaty, settlers continued to build a local economy around resource extraction. Mining, the timber trade and aggregate were the bedrock of many communities that now line the northern edge of Lake Huron.

In the 1950s, during the Cold War, uranium mining began in Elliot Lake, upstream of Serpent River First Nation. Downstream, a plant for sulphuric acid, a corrosive chemical used in uranium production, operated for about a year.

Radiation from uranium tailings leached into the watershed, eventually contaminating Serpent River First Nation’s drinking water, and the fish and beaver they’d catch. Fumes from the sulphuric acid plant damaged trees, roofs, community gardens and laundry left out to dry. Rocks nearby still bore orange stains decades later.

“The environmental cost [of the plant] has been greater than the minor benefits received at the time,” Serpent River First Nation Chief Brent Bissaillion told Anishinabek News in 2021. (Bissaillion wasn’t available for an interview for this story.)

Serpent River remains beautiful to the eye, lined with granite and white pines. Its water is also still radioactive. Health studies have shown several chronic diseases are more common in the community, as are pregnancies ending in fetal death.

“It is very toxic land,” Myra Southwind, who is from Serpent River First Nation, said at an Advocates For The North Shore Water and Environmental Resources event in September. “And that’s the thing with all the mining. Why would we want to open up more?”

The water from the wetlands that would be affected by the quarry eventually drains into Lake Lauzon, which in turn drains into Lake Huron. Wetlands filter the water that flows downstream, keeping the rest of the system clean. Quarry opponents worry residue from explosives used to blast rock could end up in the watershed, among other problems.

The main hangup so far, however, has been the turtles. For a while, it got ugly: a consultant for Darien Aggregates accused Zagorksi and her supervisor at Laurentian University of falsifying their research. The consultant later retracted the allegation and apologized, and Laurentian found the complaint was without merit. Rankin didn’t answer a question about the incident.

“If we didn’t have the Blanding’s [turtle] research, yeah, there would be shovels in the ground already,” Kirby said. “That’s the only thing that has stalled this, and some determination on the parts of a few people.”

The case of this particular quarry is a microcosm of many current environmental debates in Ontario: along with the specific issue at hand, there’s a larger concern about the rapid-fire pace at which the Doug Ford government has rewritten environmental policies over the last four years.

In 2019, the government watered down laws protecting species at risk. Among the changes was the creation of a new regime that allows industry to harm the habitats of six species at risk as long as they pay into a provincial fund, which the government plans to use for projects it says will benefit those species in the long run. That list includes Blanding’s turtles in the Ontario Shield region and the whip-poor-wills around the wetland.

Critics call the system “pay to slay,” a critique the government has argued is misleading, noting companies still have to abide by any conditions attached to their permits. The fund hasn’t been used yet, but the Darien Aggregates quarry could be among the first projects to test it out.

Gary Wheeler, a spokesperson for Ontario’s Environment Ministry, said in an email the government is still reviewing the project to decide whether it will require an endangered species permit and therefore whether a payment to the fund is an option.

And that’s just one way the ground has shifted underneath Kirby’s feet. When she began advocating against the quarry, she was talking to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Until oversight of species at risk was shuffled over to the Ministry of the Environment early in the Ford government’s tenure.

Then, the departments responsible for mining and natural resources merged and separated again. Every time Advocates For The North Shore Water and Environmental Resources found the right person to talk to or started to build a relationship in the government, everything got scrambled and they’d have to start over, Kirby said.

Take a 2019 vote by the Township of The North Shore in favour of rezoning land for the quarry. It’s an issue the advocates brought before a provincial tribunal — which was merged with others in 2021. The Ford government had also tweaked the rules governing aggregate extraction in 2019 and 2020, and some of those changes made it a moot point. The challenge was dismissed last year.

“We try this, and the door slams in our face,” Kirby said. “We try something else and they change it. It has been unbelievable.”

Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry didn’t directly answer when asked if the process has played out fairly. “As part of the application process, members of the public and other agencies have the opportunity to share their concerns with the applicant during the consultation period,” the ministry said in an email.

Late last year, another pivotal change landed: the government locked in a major switch of wetland policy, rewriting the manual that’s used to determine whether wetlands are eligible for the “provincially significant” status meant to protect them from development. That manual used to factor in species at risk that live in wetlands, like turtles, and account for the value that interconnected wetland complexes create. Now, neither factor is considered.

That makes it a lot harder for wetlands to qualify for protection. Before that, Advocates For The North Shore Water and Environmental Resources had argued the wetlands at the proposed quarry site qualified. But the changes essentially took an eraser to that idea, Kirby said.

“[It’s just] a real punch in the gut for us,” she said.

There’s still time until the quarry plan is finalized. As the natural resources ministry reviews Darien Aggregates’ application, the company is working to address concerns that came up in public consultation in spring 2016. It currently has until Feb. 27, 2023 to wrap that up.

In an email, the ministry didn’t directly answer whether it would account for the cumulative impact of aggregate operations in the area when it makes its decision.

“Aggregate extraction is driven by market demand,” the ministry said. “Some companies have more than one site because the type of aggregate it can produce is different. The supply and demand of the market determines when, how much and what type of aggregate a company can supply from individual sites. These reports are prepared by qualified professionals with experience and expertise to address potential impacts related to mineral aggregate operations.”

Kirby doesn’t have much hope her group’s concerns will actually be heard, on the aggregate application or the species at risk permit. Ontario has never denied a permit to harm species at risk, even before Ford’s tenure, the province’s auditor general reported in 2021.” And the province rarely says no to a new quarry.

“They never deny these permit applications, especially on Crown land,” Kirby said.

In early September, about 30 quarry opponents from all over the north shore sat in Kirby’s backyard for a meeting and harvest moon ceremony hosted by KiiGaDoWaak Nookimisuk, a group of Indigenous grandmothers. As afternoon turned to evening, hummingbirds zipped by and the sunset painted pastels across Lake Lauzon.

Before long, a full moon rose over the yard. Elders shared teachings with the group. Then, led by grandmothers Isabelle Meawasige and Nookimis Marly Day, they laid down a medicine bundle and gathered around a sacred fire at the edge of the water, listening as Southwind as others sang, drummed and prayed for the Blanding’s turtles, and all of the animals and waters that would be affected by the quarry.

“When I heard about the quarry going in and you know, the damage it could cause, I started thinking about those turtles,” Day said. “What’s missing through all of this is the spiritual aspect of it, and I know the power of our spirituality, what it can help do.”

Day used to have picnics next to Lake Lauzon before she moved to Baawating. Some members of her family swim there. With so much of their territory now developed and changed forever, she wonders what this area will be like in another 50 years.

Tracie Louttit, who also lives in Baawating and helped Day with the ceremony, said the group is in for the long haul.

“If no one technically gives their notice to say, ‘hey, we’re not good with this,’ then they’ll go through with it,” she said. “Well, we’ll keep doing that. We’ll keep coming here, we’ll keep doing it every 30 days if we have to.”

Updated Jan. 13, 2023, at 3:01 p.m. ET: This article was updated to include more details about the harvest moon ceremony.

Content for Apple News or Article only Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. This...

Continue reading

An Alberta government-commissioned report suggests oil and gas site companies may be able to install...

This story about a lawsuit involving First Nations in northern Ontario has deep roots — in...

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...