Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

On July 25, 2018 — 22 days after the Doug Ford government cancelled Ontario’s cap-and-trade program — Sharolyn Mathieu Vettese was invited to an hour-long webinar by the Ministry of Environment.

Two months before, Vettese, the president of SMV Energy Solutions in Cambridge, Ont., had paid $18,612.08 to take part in the cap-and-trade program as a “general market participant.” Having spent the money on 1,000 emissions allowances – each one equal to one metric tonne of greenhouse gas emissions – she planned to act like a broker to facilitate the carbon market, selling her allowances to heavy polluters who were required to buy them in lieu of reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.

Vettese had plans to invest the money she would have earned from trading these allowances into projects offering energy conservation solutions to her community. She also anticipated getting paid as a consultant for heavy emitters, explaining how the program worked and helping them purchase allowances. When then-Environment Minister Rod Phillips announced details of the program’s end in July 2018 as the new government’s first order of business, Vettese assumed the wind-down would be done slowly, and include consultation with participants. To her shock, Vettese’s cap-and-trade accounts had already been frozen. She could no longer access the money or trade her emissions credits.

“They were simply seized,” she said. “I didn’t think they’d immediately turn their back to billions of dollars.” After all, in May 2018, the Ministry of the Environment reported that, cumulatively, the Ontario cap-and-trade program had put over $2.87 billion in provincial coffers.

But just weeks after that report came out, Ford’s Progressive Conservatives won the election. At that webinar soon after the cancellation announcement, Vettese and other attendees were told that the program was being halted effective immediately. The session was briefer than the hour allocated. Vettese said officials echoed much of what the government had already said about the end of the program and addressed few questions or concerns participants raised in the conversation.

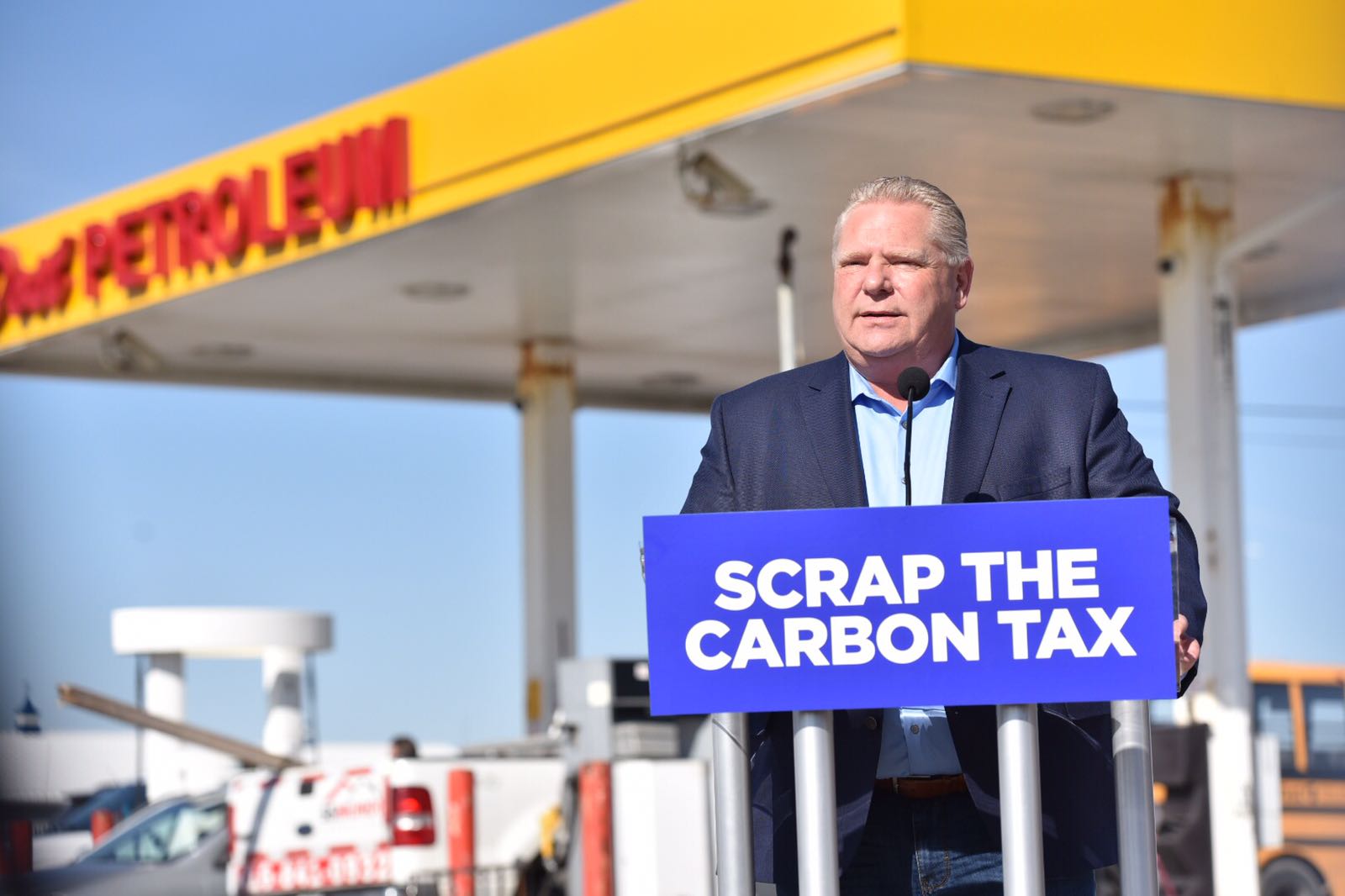

Now, there are two legal actions that have been filed against the government’s cancellation of the cap-and-trade program. Vettese is leading a class action lawsuit of businesses trying to recoup lost investments and contractual obligations, which could become the second time stakeholders have challenged the constitutionality of the Ford government’s decision to cancel the program. In a separate suit, the global giant Koch Industries is seeking US$30 million to recoup its own lost investments. Losing either suit could make one of Ford’s most high profile 2018 election campaign promises — that cancelling the program, which his party mischaracterized as a “carbon tax,” would save Ontarians money — an expensive falsehood.

The cap-and-trade program was in its infancy when the Ford government came into power in June 2018. It was designed to create a carbon market — the second largest in the world, formally called the Western Climate Initiative — between Ontario, Quebec and California, allowing participants across all three jurisdictions to buy and sell credits to pollute. Nobel-prize winning economists William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, as well as many scientists, tout programs that put a price on or regulate pollution as the most cost-effective and efficient way to quickly reduce greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to global heating. Some critics, particularly of European carbon pricing programs, say such systems often don’t have high enough caps or strong enough disincentives to actually decrease the level of emissions produced by industry.

Ontario signed the agreement with Quebec and California in September 2017, and it came into effect the next January. Any industrial facility emitting 25,000 tonnes or more of greenhouse gasses annually, as well as electricity importers and fuel suppliers, was required to participate in the program. Each company had a limit on the amount of carbon dioxide it could emit: those that exceeded the cap would be required to purchase emissions allowances from others that emitted below the limit.

The end of the program was abrupt but complicated, and left many parties unhappy. Though it had frozen participants’ accounts in the summer, the government didn’t hold its much-delayed public consultation over the Cap and Trade Cancellation Act until October 2018, a month before officially passing it. The legislation recommended repaying some participants, but it didn’t call for compensation for general market participants like SMV Energy Solutions or Koch Supply & Trading, a subsidiary of U.S.-based Koch Industries, owned by the billionaire Koch family.

At the public consultation, Koch Industries made a submission noting that five of its companies had participated in the Western Climate Initiative, with emissions purchases in both Ontario and California. Its submission stated that the cancellation would “create winners and losers through the proposed compensation scheme” and urged the government to reconsider.

The company wrote that in the aftermath of the cancellation, its emissions purchases would “be stranded in Ontario” and deemed worthless. The company did not state how much money it had spent in Ontario but suggested amendments to the legislation that would allow “all mandatory and voluntary participants” to be eligible for compensation. The Cap and Trade Cancellation Act passed in November 2018 without these proposed amendments. The $5.09 million in compensation that was eventually paid out went mainly to emitters, though it is unclear which companies received them; among the program’s 250 emitter participants were Suncor, Imperial Oil, Enbridge, Union Gas and Ontario Power Generation.

Those concerned about climate change weren’t thrilled with the Cap and Trade Cancellation Act either. In October 2019, in response to a suit brought by two environmental organizations, the Ontario Divisional Court found in a majority decision that the Ford government broke the law when it cancelled cap-and-trade without properly consulting the public, as required by the Environmental Bill of Rights.

But the judges noted that because the repeal was a done deal and the challenge itself had resulted in public consultation, “there is no practical purpose” to seeking damages or legal penance. That left businesses that had lost money, whether small, local companies like SMV Energy Solutions or an international giant like Koch Industries, with few options. Both have now chosen to try the courts themselves.

Vettese is suing the Ontario Ministry of Environment and Phillips — who now leads long-term care and recently announced his departure from politics — in a class action lawsuit. She and a yet undisclosed number of participants allege the government was wrong to deny compensation to participants that had made long-term financial and structural commitments to the cap-and-trade program. If her suit is successful, this will be the second time the cancellation is deemed unconstitutional, following the 2019 decision about the Environmental Bill of Rights.

Filed at the Ontario Superior Court in February 2021, Vettese’s suit calls both the ministry and Phillips himself “high-handed, reckless, and deliberate,” and accuses the government of showing “ a callous disregard for Class Members’ commitment, investment and reliance on the long-term nature of the Cap and Trade Program, a government-induced, and, in part, mandated program.”

In April 2021, Koch Industries filed a legacy claim against Canada under the North American Free Trade Agreement; though the United States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement superseded the older agreement in 2020, the allowances were purchased while NAFTA was still in place. Similar to the class action, the Koch claim argues the company was wrongly denied compensation, alleging it has suffered losses exceeding US$30 million.

Koch’s claim relies on the investor-state dispute settlement clause of NAFTA , or Chapter 11. This tool was designed to assess whether a company’s right to a stable business environment had been violated by a government action. Over the years, it was largely used by companies challenging government environmental policy.

Since 1994, such lawsuits have required Canada to pay damages and settlements totalling more than $263 million, according to a report by the Canadian Centre of Policy Alternatives, which makes it notable that the investor-state dispute settlement tool was removed from the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. “In removing it, we have strengthened our government’s right to regulate in the public interest to protect public health and the environment,” Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said. The Koch Industries claim will be one of the last of its kind.

The Narwhal asked Ontario’s Minister of Environment to comment on cap-and-trade-related lawsuits, and was told by spokesperson Andrew Kennedy that “while it would be inappropriate to comment on the ongoing arbitration and class action, Ontario takes its international trade commitments seriously and we are working with Global Affairs Canada to defend this case with Koch Industries.”

A spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada responded in kind, saying “the Government of Canada will always respect our international agreements, and continue to stand up for the best interests of Canadians. As this is an ongoing legal matter, we are unable to provide more information at this time.”

Industry insiders and observers told The Narwhal that the very abrupt shutting down of a billion-dollar business program has made companies reconsider or pause green investment decisions in Ontario. Adding to the uncertainty is that carbon pricing isn’t optional – provinces can only decide how to implement it.

In the absence of cap-and-trade, Ontario has seen two carbon pricing programs in the span of three years. First, the province became subject to the federal government’s price on pollution. This led to the Ontario government, along with Alberta and Saskatchewan, launching and losing a constitutional challenge of the federally-imposed carbon price at the Supreme Court in March 2021.

Forced to figure out some sort of carbon-pricing plan, Ontario then introduced Emissions Performance Standards in July 2021, which comes into effect this month. The program curiously includes some elements of a cap-and-trade system: all high-emitting industrial facilities in Ontario are required to reduce emissions through a strict criteria, or purchase compliance units, which are emissions credits, instead. With a provincial election looming, the prospect of a new government introducing an entirely new system could give potential investors additional pause.

Both the Koch Industries suit and the class action led by SMV Energy Solutions will take some time to go through the judicial system, but the eventual decisions could more clearly define the implications for industry and responsibilities of government as environment policy evolves.

Vettese remains hopeful her suit will provide some accountability. “It was shocking that the government was so delinquent in how they disrespected the law and our contracts,” she said. “It was shocking for the government to arbitrarily act on a whim.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...