5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

At the turn of the century, David Devereaux could judge the pace of his night shift by how much smoke was billowing in the sky above Lake Ontario.

Back then, Devereaux was a control room officer for Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator — a Crown agency that manages the province’s energy needs. Every evening, Devereaux would make the drive from Toronto to Mississauga, passing what was then North America’s oldest and most expensive coal plant. Known as the Lakeview Generating Station, it had four monstrous columns that blew black clouds across Lake Ontario. Every evening, Devereaux would check how many of those smoke stacks were puffing. If it was all of them, he knew he was in for a busy night.

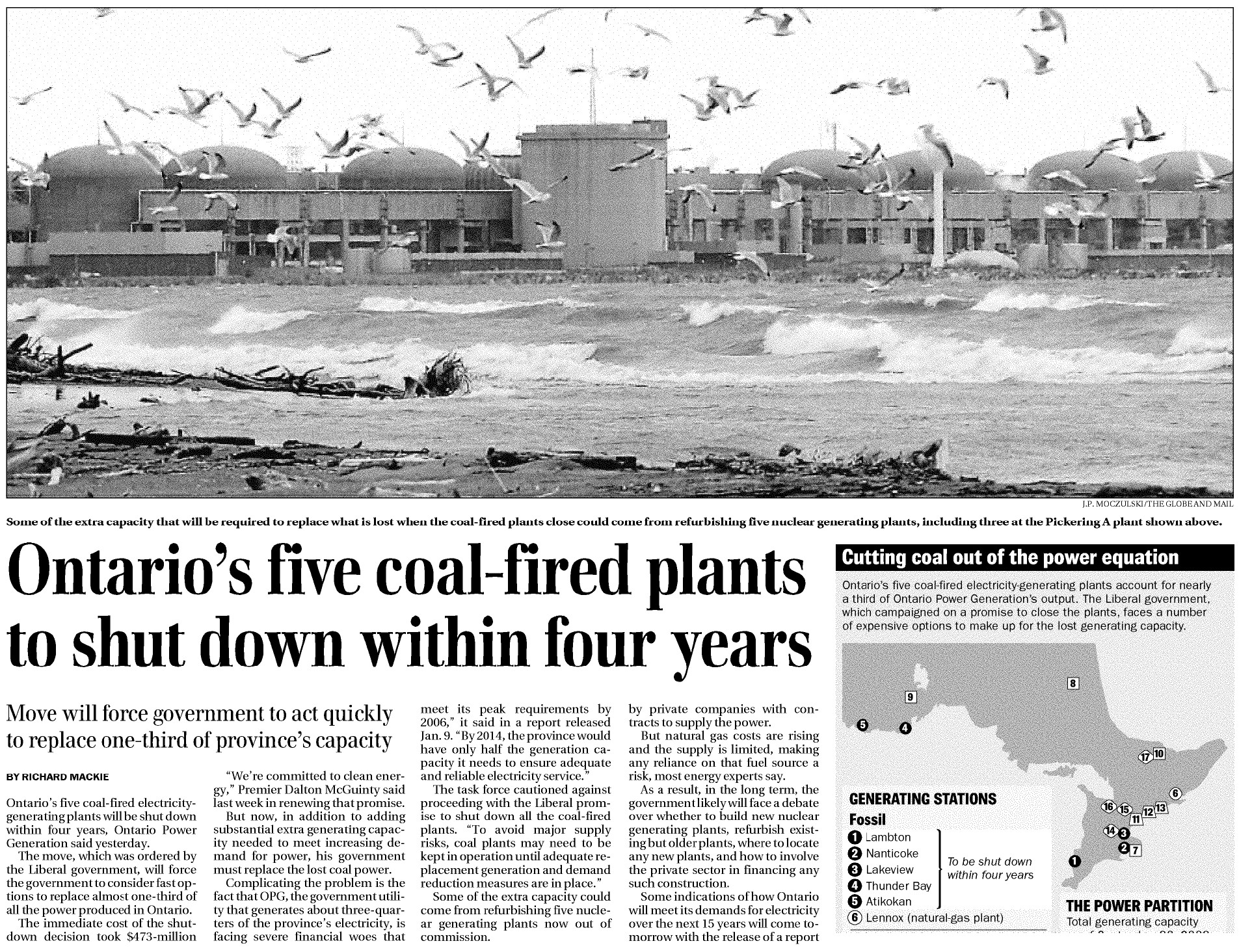

That was the case every summer. Even back then, hot days demanded air conditioning which, in turn, demanded a lot of energy. That meant the Mississauga plant, along with four others across the province — three in the south (Lakeview, Nanticoke on Lake Erie and another near Sarnia) and two in the north (one in Thunder Bay and another just west of it in Atikokan) — ran to their fullest. In southern Ontario, the smoke from these plants darkened the skies in an ominous, endless grey hue of smog — a toxic pollutant made up of mercury and sulphur dioxide, which made breathing difficult, even deadly.

The smoke from these coal plants represented a third of the province’s energy supply, but it was also a major environmental concern and growing public health emergency. By 2001 there was a chorus of calls urging Ontario to remove the source of the smoke.

“But there was no easy off button,” Devereaux, now the system operator’s director of resource planning, told me.

As an energy reporter, I hear that a lot. Some iteration of “You can’t flip a switch” is stated matter-of-factly by politicians, industry officials and experts in interviews and broader conversations. It’s both a reasoned argument and a warning signal: the energy industry is cautious about change, perhaps because changing where or how we get our electricity could mean disrupting the ability to keep our lights on.

But 2024 marks 10 years since Ontario did the seemingly impossible and flipped the coal switch off — the first jurisdiction in North America to do so. It was a defining moment in provincial history, hailed as the single largest greenhouse gas reduction initiative across the continent to date. It removed 17 per cent of Ontario’s emissions — the equivalent of taking seven million cars off the road.

Devereaux is right: it wasn’t easy. It took 17 years, three provincial governments and a massive community and industry effort. But it was a true energy transition — worth considering today as we weigh the need to stop burning fossil fuels to limit the release of greenhouse gases that warm the planet, resulting in extreme and costly weather events.

If national and international climate goals are to be met, Ontario’s next energy transition is away from natural gas, a methane-heavy, toxic fossil fuel that makes up 27 per cent of the province’s energy capacity. The challenges today are more complex but there are similar undertones to the issues Ontario was grappling with mere decades ago.

“I’ve always said that in Ontario, we’re lucky. We’ve been commissioned by history, to lead not to follow or to be dragged kicking and screaming into the future, but to leap.”

Dalton McGuinty, former premier of Ontario

Back then, the use of coal increased as the province shut down portions of its nuclear facilities for repairs. Today, Ontario is considering increasing natural gas — along with every other energy source it is able to — as a major portion of its nuclear fleet is again shut down for refurbishment or permanently.

Back then, there were concerns phasing out coal would lead to periodic power outages as energy demand exceeded supply. Today, natural gas is being pitched as an easy solution to mitigate possible power outages that may result from energy demand rapidly outpacing supply as we look to electrify everything from industry to cars.

Back then, doctors were ringing the alarm bells to mitigate a public health crisis that was, at its core, an environmental crisis. Today, doctors are once again ringing the alarm bells about the climate emergency, and how the public health effects of more frequent heat waves and wildfires will only get worse if we don’t transition seriously and soon.

“I think we’re going to have an even cleaner, greener grid,” Stephen Lecce, current Conservative energy minister, told The Narwhal last month. “I think we just have to be pragmatic and realistic.”

In 2014, Ontario proved it was possible to do that. Ten years is a long time but it’s also not that long ago. If we successfully phased out a fossil fuel once, can we do it again?

As crises go, this one was visceral. It had a clear cause and effect that could be experienced by human senses. The sky looked wrong; the air tasted toxic; the atmosphere smelled heavy. As complicated as energy issues usually are, getting off coal felt obvious and urgent.

Year by year, the impact of the fumes from coal stacks was more dire, with the number of smog days increasing from just a handful in the late 1990s to 53 in 2005. As a result, New York was chiding Ontario for the spread of smog south of the border.

In 1998, the Ontario Medical Association did something uncharacteristic and weighed in on an environmental issue. The province’s doctors became champions of clean air, characterizing smog as a “serious health risk to the people of Ontario.” In a report two years later, the association said smog was costing the provincial health care system $1 billion per year. Ontario’s doctors calculated 1,900 premature deaths were caused by air pollution each year, with countless others suffering from respiratory illnesses. In 2000, the report found pollution would lead to “9,800 hospital admissions, 13,000 emergency room visits and 47 million sick days for employees.”

One of those affected was Elizabeth Witmer’s son, a preschooler at the time. The former Conservative health and environment minister was the first MP to propose a regulation for phasing out coal at Queen’s Park. She remembers taking her son to the hospital for frequent asthma attacks — an affliction he still deals with today. “I didn’t see the link to smog immediately,” she told me. “But on every trip, there were more and more people in the emergency room.”

“My generation had accepted smog days as a reality,” Brad Duguid, the former Liberal energy minister who saw Ontario through the final stage of the phase-out, said in an interview. “I think many believed it was just going to be a permanent part of our life. But that didn’t have to be the case. Somebody just needed to say it.”

Ontario’s doctors finally did. When they spoke out publicly and privately, the provincial government was “completely pissed,” according to John Wellner, who was then director of health policy for the Ontario Medical Association. It was the first time he heard the phrase “you’re out of your lane.” At least one politician, he recalled, allegedly yelled at representatives of the medical association in a meeting with a how-dare-you tone.

“It was beyond my imagination to grasp that we could be powerful enough to fix [the smog problem],” Wellner said. “It felt too big a task but we decided to try.”

The idea of connecting the smog health crisis to energy policy was, apparently, first suggested by Bruce Lourie. Now the president of the Ivey Foundation, at the time Lourie was a consultant to the non-profit Laidlaw Foundation, thinking about smog and its impact on children’s health — and how to help.

“People don’t listen to environmentalists,” Lourie told The Narwhal. “But everyone listens to doctors.”

“Nobody had come up with the notion that you could go after the source of the problem anywhere in the world. But once we realized air quality was a health issue, we knew what had to be done.”

“And it was clearly achievable.”

Despite Lourie’s certainty, almost everyone else I spoke to about this story said that at the time they thought it was “impossible.”

“It was a David-and-Goliath battle,” Jack Gibbons told me. He co-founded the Ontario Clean Air Alliance, which started as a coalition of seven separate organizations in the late 1990s and grew to 90 organizations working together to manifest a coal-free future. He helped shape the idea of a coal phase-out with Lourie, and handed out pamphlets at Toronto subway stations to raise public knowledge of the health risks of smog.

The community movement went up against an energy industry that wasn’t enthusiastic about the shift. But they had something that is increasingly rare today: a strong political willingness — across all parties — to achieve the same impossible goal.

That consensus didn’t happen automatically. First, Witmer had to convince a divided Conservative cabinet.

People often credit former Liberal premier Dalton McGuinty for the phase out: in 2003, his government was the first to win an election with a promise to end coal, as well as the first to implement a long-term energy plan and energy efficiency measures.

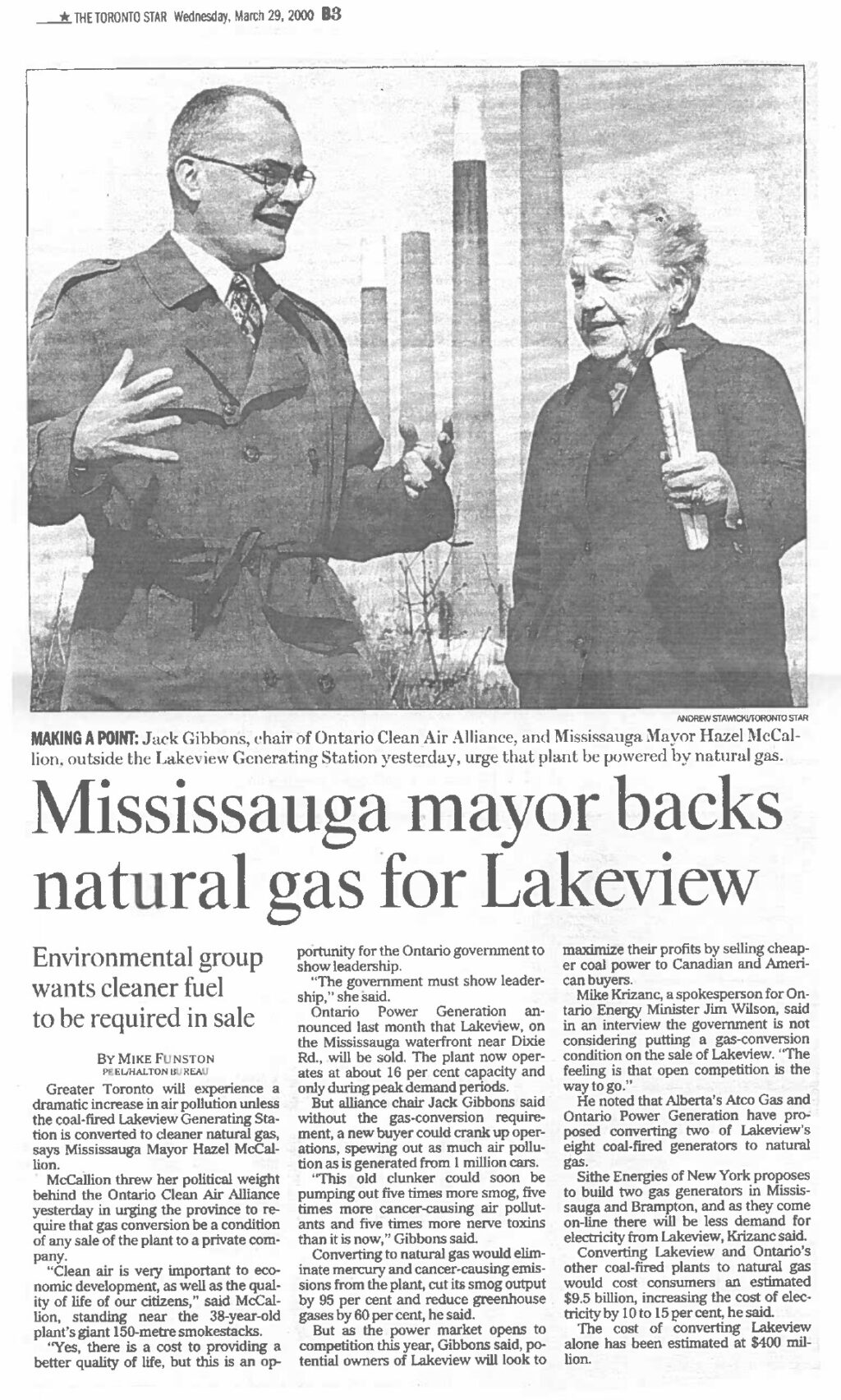

But his government was carrying a baton first picked up by two women. In March 2000, former Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion stood in front of the four smokestacks of the Lakeview coal plant with Gibbons and called for it to be converted into a natural gas facility that would release fewer and less toxic pollutants.

“Clean air is very important to economic development, as well as the quality of life of our citizens,” she told reporters before putting the responsibility to provide it squarely at the feet of the provincial government. “This is an opportunity for the Ontario government to show leadership.”

The call was heeded by Witmer, a cabinet minister in the former Conservative government led by Premier Ernie Eves. As health minister, Witmer paid close attention to the Ontario Medical Association’s report on smog. In 2001, when she became environment minister, Witmer instructed her team to prepare a plan to eliminate coal-fired power plants. The result was a regulation that pledged to phase out coal by 2015, starting with shutting down Lakeview in 2005.

“It was a very realistic plan,” Witmer told me. “Really, it was spot on. And that’s how it all started.”

Not everyone in the cabinet agreed with Witmer’s proposed regulation. There were concerns about the economic impacts of shuttering a major source of energy, from job loss to disrupting business, especially in northwestern Ontario where two coal plants were a lifeline for multiple communities. It took a while to persuade those opposed, but the regulation passed. And in the 2003 election, all three parties made a pledge to carry it through — a relief to Witmer, since her party lost and McGuinty came to power.

“We had to do this because we were all inhaling it,” McGuinty said in an interview with The Narwhal. “Every time I went into an elementary school and asked ‘who’s got a puffer inhaler?’ too many kids put up their hands.” McGuinty, too, was struck by the experiences his three sons would have in nature: “It stressed me out that we’d take our regular canoe trips through a provincial park under the darkness of a smog day.”

“I didn’t know exactly how we were going to get it done, but the longer I thought about it the more it occurred to me that coal was a 19th-century thing, it’s dirty and it’s dangerous,” he said. “I just thought, let’s be bold and ambitious.”

Getting it done, however, meant clashing with what McGuinty described as “the electricity establishment, which was almost a government unto itself.” That included the Independent Electricity System Operator, which managed energy supply and demand, Ontario Power Generation, the Crown corporation that owned all five coal plants, and what is now known as Hydro One, which distributed electricity.

This establishment “was old, it was powerful and, by and large, had done a good job of keeping the lights on for over a century,” McGuinty said. “They were very suspicious and leery of any efforts to intervene in a way that no government has ever done in Canadian history.”

At the time, coal was the cheapest and most reliable source of electricity in the province. The industry argued phasing it out would mean more expensive power for everyone, which could turn businesses away. That tradeoff is familiar today: a short-term disruption for long-term gains. But in Ontario, the energy industry is largely owned by the province and run by government decree. Even if there are qualms, what the government says has to be done.

“I’ve always said that in Ontario, we’re lucky,” McGuinty said. “We’ve been commissioned by history, to lead not to follow or to be dragged kicking and screaming into the future, but to leap.”

When the government tried to do so, “the industry said, ‘McGuinty, you’re crazy, you can’t do this’,” the former premier said. “We certainly felt resentment, a sense that we were interlopers who were interfering in matters we knew very little about. But we intervened, nonetheless.”

“Policy clarity is always helpful,” Devereaux said when I asked about the industry’s response to the coal phase-out. Execution, he said, is more complicated. Ontario Power Generation took steps to work with unions for an orderly shutdown that trained nearly 1,000 coal workers for jobs at new natural gas or nuclear facilities and helped municipalities grapple with a changed economic and energy landscape.

In the course of trying to understand how to phase out coal, the energy industry’s concerns “may come across as opposition,” Devereaux told me. “I don’t think it’s intended that way. It’s more like, ‘how do we do this?’ ”

It took a lot longer than everyone wanted to get to the finish line. But in 2005, Lakeview Generating Plant was the first to shut down and literally fall. The four smokestacks that dominated the Mississauga skyline were toppled to the ground one after another. In April 2014, the Nanticoke Generating Station on Lake Erie — once the world’s largest coal-fired power plant and the biggest polluter in the province and across Canada — burned its final supply of coal. It was demolished four years later as an audience of employees cheered, and is now being considered as the site of a new power plant, possibly nuclear.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say there are thousands of more Ontarians living healthier lives because of the coal phase-out,” Duguid said. “Bold things, important things are often very challenging to do. When you’re doing something nobody has done before you’re going to run into things you don’t expect. That doesn’t mean you don’t do them. And that you don’t try them again.”

The impact was immediate. The first year without coal-powered plants — 2015 — was the first year since 1970 without any smog warnings in southern Ontario. The sky was blue. Breathing was easier.

A decade on, Ontario’s coal phase-out feels mythical, magical and even enviable. But everyone involved is quick to tell me that it wasn’t an easy endeavour, just the first time it had ever been tried and successfully accomplished — and its lessons aren’t easily transferable, nor its solutions perfect.

“If it looks like an easy thing to do, that’s, I think, a testament to how [the energy industry and the province] was able to deliver that,” Kim Lauritsen, senior vice-president of enterprise strategy and energy markets at Ontario Power Generation, told me. “Calling it easy somewhat diminishes what a heavy lift it actually was.”

“Ultimately, not all transitions are the same,” she added. “And there is no one silver bullet solution.”

Each one involved a lot of planning, a lot of communication and a lot of experimentation.

The irony is that to move away from coal, Ontario increased nuclear power, but also opened the door to more natural gas — a recommendation that came from doctors, local politicians and energy officials. The Independent Electricity System Operator reports that in the time it took to phase out coal, the province nearly tripled its ability to generate power from natural gas, which produces about half the carbon dioxide per unit of energy that burning coal emits. One of the coal plants was converted to a gas facility, and brand-new gas plants were built across southwestern Ontario.

“That was the only real alternative we could turn to,” McGuinty said, because a renewable industry didn’t exist yet. By the time the last coal plant was shuttered, wind, solar and biomass accounted for seven per cent of Ontario’s electricity production.

And while nuclear saw the greatest increase in coal’s wake, natural gas was the reason Ontario could phase out coal without disruption, Devereaux said. It “was like-for-like and unlimited fuel, but with lower emissions,” he said. “You could turn it on when you wanted to, turn it off when you wanted to.”

But over the past decade, we’ve learned much more about the devastating climate impact of the methane-heavy gas. Methane is emitted as a byproduct of natural gas production, and can also leak from equipment both during extraction and transportation through pipelines. When released in the atmosphere, this unburnt methane has been found to be 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide; it is responsible for about 30 per cent of the rise in global temperature.

In spite of this, today, the Doug Ford government is looking at increasing Ontario’s reliance on gas generators, suggesting the path away from this fossil fuel isn’t clear or definite. While Environment Canada reported this summer’s heat waves broke records across Canada, Ontario communities don’t experience the immediate impacts of emissions from natural gas as they did the smog produced by burning coal. The natural gas industry has also become incredibly powerful, thanks to its ability to provide affordable, reliable electricity as the province’s hunger for it grows.

The chorus arguing against gas is slowly growing louder, one city at a time. Gibbons, who once stood beside the Mississauga mayor calling for a move in the fossil fuel’s favour, now crusades against its continued use. Gibbons said the same argument used against coal 10 years ago is applicable to natural gas today: “Phasing out gas is one of the easiest, most cost-effective ways to reduce our greenhouse gases now.” He adds that any increase in natural gas to manage short-term energy supply crunches will mean losing 50 per cent of the pollution-reduction benefits Ontario achieved by phasing out coal.

The Independent Electricity System Operator now projects the province can move away from natural gas by 2030 — in six years — if the will is there.

The Ford government does not currently have a policy to phase out natural gas. In fact, it has taken a technology-agnostic approach to boosting energy supply that has made climate and sustainability advocates question the government’s interest in moving away from fossil fuels.

That’s not to say Ontario can’t achieve an environmental and energy success like the coal phase-out again. The politicians and advocates that delivered it have clear advice for those grappling with energy transitions today. Be practical. Do it carefully. Make realistic, honest promises. Make measured plans. Trust the expertise. Don’t let people’s power go out. Consider the costs of energy but also the costs of the climate emergency. Work collaboratively. Take the long view.

“If we start making commitments to ban gas that are not realistic, it could all come crashing down on us,” Duguid said. “You could set the electrification movement back decades.”

The consequences of messing up could challenge our ability to keep the lights on. And, as Duguid knows, even a transition that succeeds in the long term can spell the end of a government first. The period over which the coal phase-out occurred was associated with major increases in electricity prices, particularly for residential consumers, which played a significant part in McGuinty’s resignation from government.

But, as the coal phase-out proved, the right solution could be the make-or-break moment for a jurisdiction’s ability to provide both a clean environment and reliable, affordable electricity.

The lesson of Ontario’s energy history is that there needs to be a strong will from both the public and the people in power to facilitate a transformative shift. There needs to be an understanding that change takes time, so none can be wasted.

The transition ahead could be even more impactful than ending coal because it requires a new level of thinking that embraces rapidly evolving technologies and global collaboration.

“It’s so interesting to be here, thinking about all this,” Devereaux, from the Independent Electricity System Operator, said.

“More interesting than 10 years ago?” I asked.

“I think so,” he said. “I really do. The biggest challenge is making sure whatever plan we come up with is realistic.”

In other words, you can’t flip a switch.

Editor’s note: The Narwhal’s Ontario Bureau has previously received funding from the Ivey Foundation. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, no foundation or outside organization has editorial input into our stories. All of The Narwhal’s funding is disclosed annually.

Corrected Dec. 9, 2024, at 8:45 p.m. ET: This story has been updated to correct a line stating the Nanticoke Generating Station was in Thunder Bay, Ont. The former coal plant was actually in Nanticoke, Ont., on Lake Erie.

Updated Dec. 10, 2024, at 12:48 p.m. ET: This story has been updated to clarify that unburnt methane is released during the production and transportation of natural gas, and it is that methane that is more harmful than carbon dioxide emissions.

Podcast: Download

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...