Just off the rugged coastline of Georgian Bay lies a private island where Ontario has made a big exception to the hunting rules followed just about everywhere else in the province.

Most places in Ontario have an open season on deer that lasts about two weeks. Up until recently, it lasted 11 weeks on Griffith Island, just north of Owen Sound, where the luxurious Griffith Island Club serves an exclusive clientele of North American elites. And earlier this year, the Doug Ford government quietly extended the deer hunting season again for Griffith Island and neighbouring Hay Island, which is also privately owned — hunters in both places can now hunt deer with rifles there for 13 weeks, the longest season in the province.

Griffith Island Club doesn’t list its current membership fees on its website, but in 1975 it charged $20,000 to join plus annual dues, according to a Maclean’s article published that year. Members and guests over the past half-century include MPPs and MPs from various parties, along with professional sports executives and plenty of Bay Street types. When the province proposed the idea for an extended season on Ontario’s environmental registry last November, it said the change would allow the Griffith Island Club to “better manage the islands [sic] deer populations and increase opportunity for clients and club members.”

The office of Natural Resources and Forestry Minister Graydon Smith didn’t respond to multiple emails and calls from The Narwhal asking why it has such an interest in expanding the hunting privileges enjoyed by members of the private club. The office of Premier Doug Ford also didn’t answer when asked whether he or any MPPs in the Progressive Conservative caucus have ever been there.

The Narwhal also asked Griffith Island Club management questions about its price of admission, membership list and how exactly it ended up as the beneficiary of the policy change. In an email, club chairman Marc Dumont didn’t answer most of the questions, including whether the club had asked the government for the extension — Ontario’s lobbying registry shows no record of contact between the Ford government and the club.

“Hunting regulations are set by the Province of Ontario, and the club has no influence over the establishment of seasons, or any other legislation relevant to our operations or how these are publicly communicated by the minister,” Dumont wrote.

“The club, like any other business and employer in Ontario, fully complies with all provincial and federal legislation to legally operate. The club does not release any information that is considered personal or confidential in relation to our members and their activities.” Dumont also didn’t answer questions about why the club’s site advertises wild turkey hunting even though Ontario’s publicly-posted regulations don’t allow the bird to be harvested there.

While the dates for Ontario’s hunting seasons in most areas are posted in an online provincial guide, that site contains no such information for Griffith Island and Hay Island, saying only that each has a “unique season” and that the public can call for more information (two other areas in Ontario have the same disclaimer, but those exceptions seem unrelated to the islands). This opacity has drawn criticism, especially about whether it’s fair for the 70 or so members of the club to enjoy a longer hunting season than everywhere else.

Lawrence Kowal is from the Kawartha Lakes region, northeast of Toronto, and has hunted for years near Haliburton, Ont. He heard about the changes to the hunting season on Griffith Island when a friend forwarded him the environmental registry posting, in which the idea was lumped in with a series of other adjustments to Ontario hunting regulations.

“Why would you have to add two more weeks to a hunt season?” he recalls thinking. “That seems excessive.”

The more he looked into it, he said, the more he saw red flags.

“It was an absolute absence of information,” he said. “There should be more transparency.”

The Ontario Federation of Hunters and Anglers, which represents over 100,000 members in the province, formally opposed the extended season when the government proposed it. The federation’s manager of policy, Mark Ryckman, said in an interview that some members were concerned, and that the organization generally doesn’t support landowners getting preferential access to hunting opportunities.

“Ultimately these are public wildlife resources or natural resources, managed on behalf of all Ontarians by the provincial government, so we don’t want to see hunting or fishing for that matter… become a pastime that only the wealthy can afford,” Ryckman said.

Griffith Island has been a playground for the rich and powerful for decades

Griffith Island is about 2,300 acres, though reports of its exact size vary. The federal government maintains a historic lighthouse on one side. The rest is owned exclusively by the Griffith Island Club.

The modern-day club can sleep 22 guests at a time. They’re fed gourmet meals by a private chef and treated with access to a games room and sauna. Photos on the club’s website show cushy bedrooms and a woodsy guest lounge, adorned with glossy leather chairs, a pool table and a stag’s head mounted on the wall.

An airstrip on the island allows some to fly in on chartered aircraft (no jets, though — those use the nearby airport in Wiarton, Ont.). Many cross over on the club’s ferry, Islander II. Guests can also fish, swim in the turquoise water or shoot clay targets on about a dozen courses.

“The Griffith Island Club has a limited number of membership opportunities available to suitable candidates,” its website says. “All candidates are subject to a review process by the Club Board, with circulation to all members.”

On Facebook and Instagram, visitors have listed the island as their location when posting photos of their time there. The pictures show ladies in billowing white dresses at the steps of a private plane, a hunter green napkin embroidered with the club’s logo and people with guns and neon orange vests posing by the deer and heaps of birds they’ve bagged. One photo taken in front of a gun rack shows a teenage boy in a fur coat wielding a wad of cash the size of his head in one hand and an even larger bottle of brown liquid in the other.

Personalities like NHL executive Brian Burke and Chip and Pepper clothing line cofounder Chip Foster have made appearances at the club, as have former Progressive Conservative MPP Michael Harris and the former Conservative MP for the area, Larry Miller.

The club’s website boasts of the island’s history stretching back to “the landing there of Samuel de Champlain,” but the Saugeen Ojibway Nation traces its history there much further back. The nation didn’t respond to a request for an interview, but has said the Bruce Peninsula, which Griffith Island sits next to, and the surrounding area of Georgian Bay was stolen from them by the Crown in the 1800s. In an 1899 newspaper ad, the Department of Indian Affairs announced that it would accept bids for Griffith Island and its timber.

The island passed through various hands in the 20th century, including late Toronto Maple Leafs owner Jack Bickell, also a member of the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame, and a group of his businessman buddies. It later became the property of Frigidaire, then owned by General Motors. The company used it for the “schooling and recreation of GM executives from all over the continent,” The Globe and Mail wrote in 1957.

It was about that time when Griffith Island started appearing to be subject to different set of rules.

At the time, no deer hunting was allowed in the rest of Grey County, which Griffith Island is a part of, but it happened year round on the island, the paper reported. The Liberal MPP who represented the Bruce Peninsula at the time, Ross Whicher, raised the issue in the legislature, arguing that it was an injustice for deer hunting to be allowed so freely on the island when his constituents on the mainland would be fined for doing the same thing, even if they were trying to feed their family.

The company hung onto the island for about 13 years before selling it: “GM’s interest in it declined after one of its senior executives was killed in a hunting accident several years ago,” said a 1975 article in The Globe and Mail.

By then, Griffith Island was owned by the group of wealthy businessmen who started the nonprofit Griffith Island Club. Its ties to Queen’s Park go back to its founding: the club’s first president was former Ontario premier John Robarts, a Progressive Conservative. Other early members included Frederik Eaton, president of Eaton’s of Canada, and a corporate director of the company that owned the Labatt brewery.

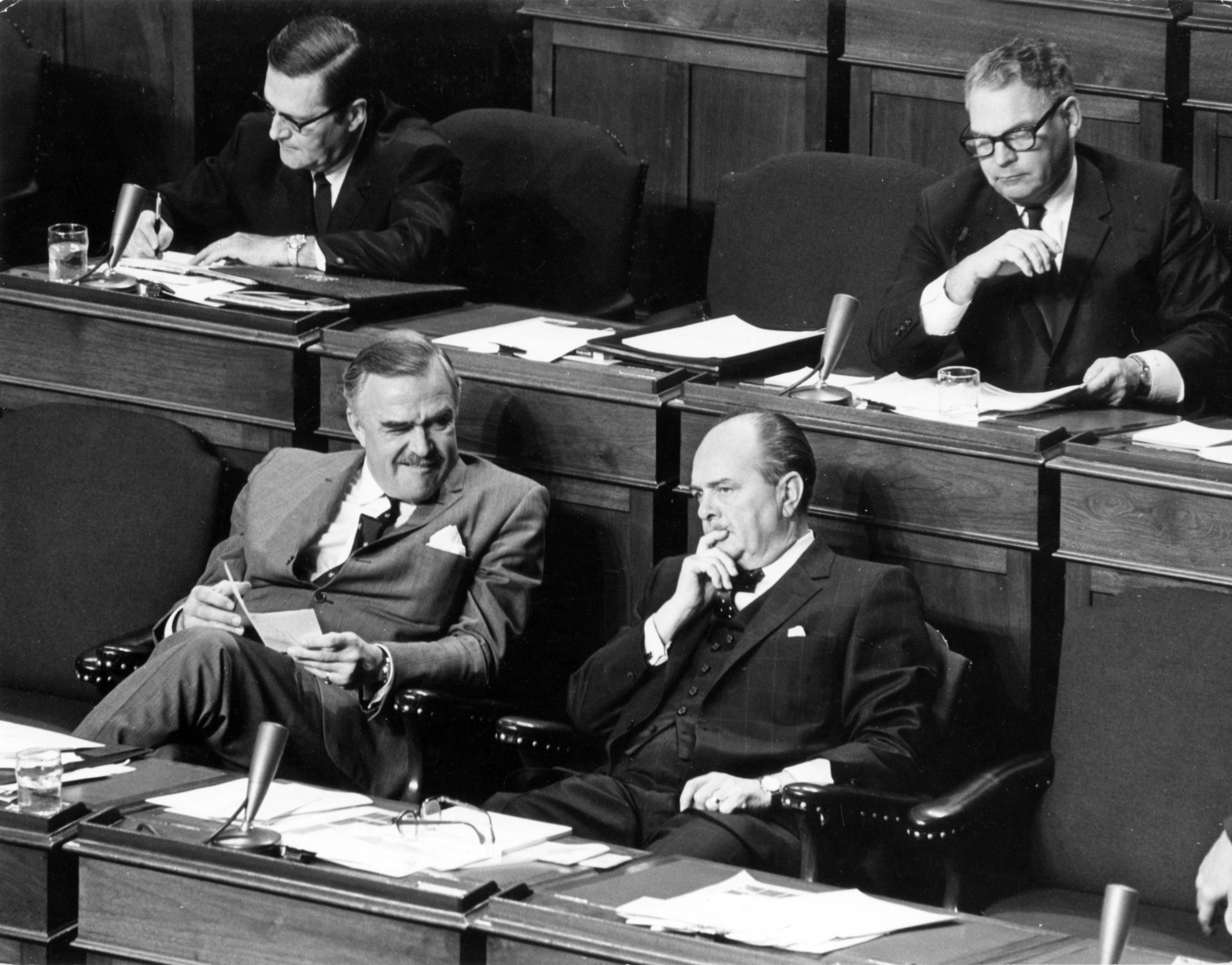

In 1975, a Windsor Star reporter who visited the island found that hunters there were allowed to shoot pheasants for seven months, though the season elsewhere in the province was just two weeks long. Deer seasons lasted a few days on the mainland, but two months on Griffith Island. The same year, the club’s manager paid a $100 fine for hunting without a license. Members of Ontario’s cabinet hunted there at the time — a former club manager gave the Windsor Star blunt assessments of their abilities in 1976, saying natural resources minister Leo Bernier was a “good hunter,” but transportation minister James Snow “doesn’t know a cockbird from a hen pheasant and can’t hit a barn door.”

After the Windsor Star began publishing stories about the club, an MPP questioned then-Ontario premier Bill Davis about it at the legislature, referencing reports of armed guards on the island, and the club serving alcohol without a liquor licence.

“I have been there for dinner on one occasion,” Davis said, redirecting questions about it to another minister. “I have never hunted at Griffith Island. In fact I have never hunted anywhere.”

According to media reports, Griffith Island’s lax rules and mystique persisted: by 1983, the Toronto Star — which investigated reports that club staff were making just $45 per day for 16 hours of work — said that former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had been spotted there. The younger Trudeau has never visited Griffith Island, with or without his father, the Prime Minister’s Office said in an email.

“Don’t we have any rights?” the club president at the time, William Doherty, said to a Star reporter. “You’re going to write about us whether we want you to or not, is that quite cricket?”

The desire for privacy was a theme then, too: amid a 1978 controversy over a planned and subsequently cancelled foxhunt at Griffith Island, the secretary for the club said he didn’t “think it’s anyone’s business… It’s a private club, we pay our taxes, we’re within the law.”

In 2004, The Globe and Mail reported on a trip to the island taken in fall 2002 by then-Hydro One chair Glen Wright, who expensed a trip to Griffith Island to the utility provider in the years before it was privatized. Wright’s bill to the Crown corporation was over $5,000 for a group trip: his guests included a Progressive Conservative cabinet minister, Tory political advisors and two Hydro One union leaders. The paper reported it cost $750 per night, and that Wright’s expenses included $297 for shotgun shells and $178 for 17 pheasant pies. Wright reimbursed Hydro One after he learned The Globe planned to report on the expenses.

By 2003 — the earliest year for which Ontario’s hunting regulations are online — the deer hunting season on Griffith Island had become an expansive 11 weeks. It stayed that way until being lengthened this year.

There isn’t much out there about what happens at the Griffith Island Club today. The club has no public membership list, and the list of directors on its corporate registration appears outdated — for example, it includes current Porter Airlines CEO and president Robert J. Deluce, who told The Narwhal that he hasn’t been involved with the club for at least a dozen years and can’t remember much about the membership process. “Basically I lost interest because I was far too busy at Porter,” he said in an email.

Others listed on the registration include a variety of Bay Street executives, big names in the road construction industry, a former CFL player, and Niagara Region Coun. Vince Kerrio — who is seeking re-election this fall and didn’t respond to an email sent through his campaign website. Other listed members who have mentioned visits to the island publicly include corporate leaders of trucking and mining companies.

Along with social media, other snippets of information can be found in job postings. The club is staffed year-round, though members can only visit from April until December. A recent posting for a receptionist describes managing the club’s membership list as a task that requires “absolute discretion and confidentiality.” Another for a head gamekeeper says candidates should be able to raise over 25,000 gamebirds, duties which include breeding and incubating eggs. Other workers who manage game on the island make $43,000 per year, according to a third posting, and pay $100 bimonthly to live onsite.

Other Ontario deer hunters object to what seems like special treatment for Griffith Island

Across most of the province, hunters have voluntarily reported how many deer they harvest every year, with numbers online going back to 2008. Hunters on Griffith Island did not report any until the practice was made mandatory in 2019. The same is true on nearby Hay Island, which is also private and enjoys an equally long season: there, only one or two deer have been bagged each year for which there are records.

On Griffith, hunters have reported bagging roughly 70 deer per year, about the same as the number of licenced hunters active on the island, according to provincial data. Kowal, who hunts in Haliburton, said that’s a lot — a young deer would weigh at least 100 pounds, and big bucks can be four times that.

“What they do with it is up to them,” Kowal said. “But that’s an awful lot of people getting a very large serving of venison.”

Usually, the Ontario government decides the length, timing and other specifics of local deer hunting seasons by considering how many of the animals live in an area and consulting with stakeholders, including experts in wildlife management. Rifle hunting is most tightly controlled — hunters using less powerful weapons, like crossbows, can hunt for longer, in part because they tend to bag fewer deer.

Ryckman, of the hunters and anglers federation, said there could be a biological reason why Griffith Island needs a longer deer hunting season. The balance between predators and prey can easily be thrown off on islands, resulting in either too many deer — which could necessitate a longer hunting season — or too few.

But if that’s why the Ontario government has given Griffith Island an extended season for so many years, the province hasn’t said so: along with the current Progressive Conservative government, the Ontario Liberal Party didn’t answer questions from The Narwhal about why it allowed an 11-week hunting season on Griffith Island during the most recent 15 years it was in power. The party also didn’t answer when asked whether any of the party’s current MPPs or staff had ever visited the island or been a member of the Griffith Island Club. The Ontario NDP and Green Party, likewise, did not agree to an interview about Griffith Island.

And if biological concerns are a problem, it may be odd that the longer deer season does apply to Griffith Island and neighbouring Hay Island — which sold to a new owner last year for $14 million, after being advertised as an “idyllic retreat” with an “extended hunting season” — but not White Cloud Island, which is just a stone’s throw away. On the province’s online proposal to add two weeks to the season on Griffith and Hay, one comment is a complaint that the extended season doesn’t apply on White Cloud, where landowners are “not huge corporations but private people who own land on a private island.” The comment, which was anonymized, said the move amounts to “nothing but someone catering to big money and ignoring others who have spent their own money. It is a biased and blatant example of favouritism.”

Ryckman said that while the federation is “opposed to the exclusive access and the very long season provided to the owners of Griffith Island… we don’t really have any population health or sustainability concerns about the deer population on the island.” For that reason, his organization is unlikely to push the issue much further: “The primary focus of the OFAH is the conservation of the resource,” he added.

Kowal said it’s unfair that Griffith Island gets preferential treatment. He gets exactly 13 days to hunt deer, rain or shine — he usually spends them in the bush with friends, and if the weather’s bad, they don’t have the luxury of going again. They limit what they hunt and eat what they harvest, always thinking about conserving the deer so they’ll be around next year.

‘It’s something that you have to be mindful of and protect,” he said. “It’s not mine to take without some form of rules.”

To him, that’s not the spirit of what’s happening on Griffith Island.

“Everyone should have to play under the same rules. They don’t. They’ve been given privilege, and done a very good job of keeping it out of the public view.”