Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Ontario Power Generation, the province’s largest power generator, seriously started thinking about electric vehicles only five years ago.

Back then, Heather Ferguson recalls, charging stations across the province were few and poorly maintained. As the automotive and power industry started considering electrification more and more, OPG had an opportunity to “refresh” the charging infrastructure and think about the problem “in a whole new way.”

“It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to understand we had a role to play,” says Ferguson, OPG’s senior vice-president of business development, strategy and corporate affairs. “We produce electricity and the connection to electric vehicles is pretty straightforward.”

Fast forward many conversations with stakeholders and years of planning, OPG and Hydro One, the province’s largest distribution utility, announced a new joint venture: Ivy Charging Network. The company is funded in part by both companies, as well as $8 million from Natural Resources Canada, with the goal of launching 160 chargers at 73 locations, each an average of less than 100 kilometres apart, by the end of the year. As of mid-December, 28 of those stations were fully operational but Ivy hoped to have the full system up and running by spring 2022. It will make Ivy the largest fast-charger network connecting Ontario from Kenora in the northwest to Cornwall in the southeast.

The company was created to solve “range anxiety,” or the fear of buying an electric vehicle in Ontario due to a lack of charging stations. Soon, for $9, electric vehicle users will be able to charge for half an hour to drive 150 kilometres — or about the distance from Toronto to Orillia.

“The idea is we’ll be able to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles,” says Matt Vines, co-president of Ivy Charging Network. “We’re going to build the network and then continue to proactively grow it.”

“It’s a chicken and egg thing,” says Ferguson. “If you don’t have charging infrastructure, people aren’t going to buy EVs; if you don’t have EVs, people aren’t going to build charging infrastructure. So I think OPG and Hydro One decided to take a bit of a bold leadership role here and lay out the critical infrastructure for this electrification thing to happen.”

Ivy Charging Network is the latest initiative in a string of electrification projects that are being set up across Ontario. For the most part, they are being spearheaded by public utilities and municipalities — Hydro One is a 60 per cent private, 40 per cent public utility, while OPG is a Crown corporation. Many of the electrification projects have received financial backing from the federal government, which has contributed funding to 52 proposals in Ontario as part of its Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program. Such initiatives are now shaping political discourse ahead of a provincial election this spring, forcing Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government to enter a conversation it has largely stayed out of.

Just this month, Ivy announced a series of agreements with ONroute, which had promised chargers five years ago but never followed through, to deploy chargers on Ontario’s 400-series highways by next summer. The agreements also include retailer Canadian Tire and, surprisingly for many in the electric vehicle industry, Ontario’s Ministry of Transportation. While the ministry offered no financial assistance, it owns the sites leased out to ONroute so its participation was needed for this agreement to move forward. Vines says it was “a priority” for the Ministry, that it was part of the negotiations and “extremely supportive.” (Minister of Transportation Caroline Mulroney declined to answer The Narwhal’s questions.)

This kind of positive support is a stark shift for the Ford government.

Since coming into power in 2018, the government scrapped an existing buyer incentive program, which provided up to $14,000 on the purchase of an electric vehicle. (For comparison, buyer incentives exist in eight provinces and territories.) Ford also removed a $2.5 million incentive program that helped homeowners install their own charging equipment. The government also deleted electric vehicle charging station requirements in Ontario’s building code and ripped out a couple dozen public electric vehicle charging stations that had already been installed.

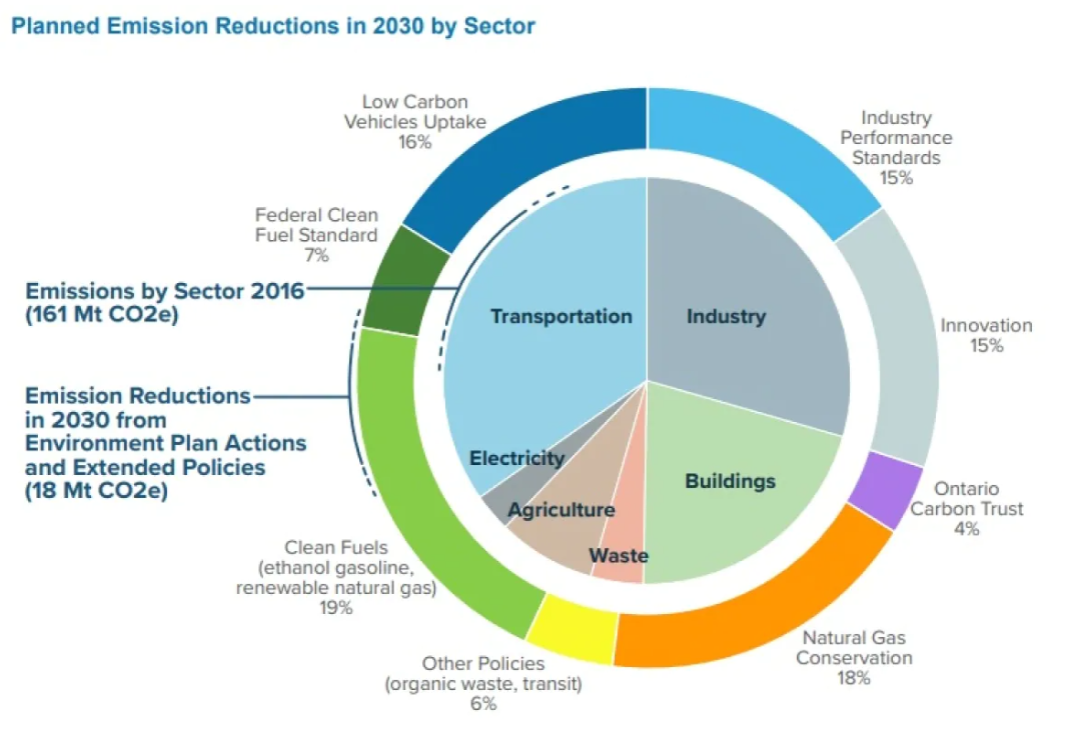

“It only benefitted millionaires who could afford Teslas,” Premier Doug Ford said at the time. The government presented this move as a cost-cutting measure regardless of the fact that his government’s Made in Ontario Environment Plan, released in 2018, projected “low carbon vehicle uptake” would account for 16 per cent (or a sixth) of the province’s emissions reductions. Right now, transportation causes over a third of the province’s emissions.

Still, Ford didn’t change his tune. “I’m not going to give rebates to guys that are buying $100,000 cars — millionaires,” he told CBC last month.

The vacuum of electric vehicle policies and provincial investment dollars has had rippling impacts across Ontario. To start, the Canadian arm of Tesla took the government to court, claiming it was treated unfairly in the cancellation of the electric vehicle incentive program, and was arbitrarily exempted from a program that allowed customers of other cheaper electric vehicle brands to continue receiving rebates during a transition period. Tesla won the court challenge.

In the absence of dedicated policies, sales of electric vehicles in Ontario dropped by over 50 per cent in 2019.

According to data from Statistics Canada, electric vehicles represented 1.8 per cent of new light duty vehicle sales in Ontario in 2020, which was below the global average of 2.7 per cent and well behind the Canadian national average of 3.5 per cent. In the third quarter of 2021, according to data from IHS Markit, electric vehicles represented 3.1 per cent of new vehicle registrations in Ontario, compared to 13 per cent in B.C., which has a $3,000 incentive, and 9.9 per cent in Quebec, which has an $8,000 incentive. Last year, there were more electric vehicles registered in Vancouver than in all of Ontario.

But then a series of industry shifts happened that forced the Ford government to take the future of electric vehicles in Ontario more seriously.

Sometime in the summer of 2020, Ford called Magna founder Frank Stronach, an automotive tycoon who has twice donated to the Progressive Conservatives in 2021 and met with Ford once before in 2019. The premier was seeking advice on how to create jobs in the auto industry. Two years earlier, on the campaign trail, Ford vowed to bring back 300,000 manufacturing jobs he said the province had lost under Liberal governments. According to a report by The Auroran, Stronach came up with a solution: Focus on electric vehicles at home.

As both Ferguson of OPG and Vines of Ivy note, Ontario is in an ideal position to reap the benefits of electric vehicles. The province has a largely clean electricity system so the best way for it to further reduce its greenhouse gas emissions is to focus on the highest-emitting sector: transportation. OPG and Hydro One, along with many other utilities across the province, are leading the way, Ferguson says.

“You take all the heavy lifting you’ve done to build out an extraordinary clean system and you power the transportation sector,” she says.

Automakers are also taking note. Ontario is the only jurisdiction in North America where five major automakers build vehicles: Stellantis, General Motors, Ford Motor Company, Honda and Toyota. In 2020, three of those companies — General Motors, Ford and Stellantis — announced billion-dollar electric vehicle manufacturing investments. Stellantis’ Windsor assembly plant will transform to build more electric models, with plug-in and electric vehicle battery manufacturing starting in 2024. General Motors will invest nearly $1 billion to bring the production of the BrightDrop EV600 electric vehicle to its manufacturing plant in Oshawa. The government of Ontario and the federal government each committed $295 million toward the renovation of Ford’s Oakville assembly plant, which will exclusively build electric vehicles.

“We all were waiting with baited breath to see if this was going to cause Premier Ford to change his tune on electric vehicles,” says Joanna Kyriazis, a senior policy adviser at Clean Energy Canada.

It took a while, but it happened.

Government data shows that electric vehicle manufacturing is already an economic win — in 2019, it contributed $13.9 billion to Ontario’s GDP. And there’s a burgeoning market: global sales of electric vehicles in 2030 are expected to be 15 times what they were in 2020.

Last month, the Ford government released Phase Two of its Driving Prosperity plan, which puts an emphasis on manufacturing electric vehicles in Ontario. In it, 2030 looms large. Ford pledged to meet four key targets by 2030: “reposition vehicle and parts production for the car of the future, establish and support a battery supply chain ecosystem, innovate in every stage of development, invest in Ontario’s auto workers.”

The plan states the government’s goal is to see 400,000 electric vehicles manufactured in the province in the same time frame and also establish a new electric vehicle and hybrid assembly plant. It cites industry projections that by 2030, one out of every three vehicles sold globally will be electric and that the market volume will be 31.1 million vehicles. It’s estimated that there will be half a million electric vehicles in Ontario by then, which currently has a population of more than 14.5 million, versus 635,000 electric vehicles projected for B.C. at that time, with a third of the population. Hydro One expects electricity demand to grow around 15 per cent annually between 2022 and 2040 to meet this surge.

The battery aspect is an economic opportunity, albeit a complicated one. In 2019 alone, Ontario produced more than $10 billion worth of minerals, accounting for almost 25 per cent of Canada’s total mineral production. At the top of the list of naturally occurring minerals in Ontario are graphite, lithium, nickel and cobalt — all crucial raw materials in the production of batteries for electric vehicles, and many of which are found on First Nations land. Ontario’s Driving Prosperity plan is heavily reliant on taking advantage of critical minerals found in the Ring of Fire, with Ford and several ministers promising to work in concert with First Nations communities in the region to build an electric vehicle mining hub that will benefit all.

Earlier this year, three First Nations communities in northwestern Ontario — Neskantaga, Attawapiskat and Fort Albany — declared a moratorium on Ring of Fire development until further study has been done to ensure environmental risks are mitigated and First Nations are fairly consulted. Their concern is that communities will be “seriously and permanently desecrated by massive-scale mining in the Ring of Fire.” And as mining giants battle over rights for the region, there are questions about whether accessing the minerals is truly economically viable.

Ian Klesmer, director of strategy at The Atmospheric Fund, is encouraged by the government’s new enthusiasm for electric vehicles. “I think that’s a recognition among the province that [electric vehicles] are really important, both as an economic opportunity and also as an environmental opportunity,” he says. “I think right now the key is to focus on how we can put the right policies in place to scale that ambition.” Part of that, Klesmer says, will be to hear the government offer clear timelines and more details about how Ontario will “make EVs a central part of our future.”

Ontario Environment Minister David Piccini tells The Narwhal the government is “creating a climate where we’re seeing massive EV investment and an actual coherent strategy for this province that is increasing supply and driving down costs.” He calls this plan “a made-in-Ontario solution that’s creating wealth, that’s creating jobs and that’s driving electrification.”

Piccini says his government’s strategy is in line with other countries who are also pushing electric vehicles. “When I was at [the UN climate change summit] I spoke with the head of the Transportation Committee in the U.K., and everybody’s grappling with it together,” he says. “But as we have those sorts of debates and discussions one thing we can immediately do is create a competitive climate for manufacturing.”

But some critics are hesitant about this approach, arguing electric vehicles are only beneficial if they come with a whole myriad of policies that encourage driving less and taking public transit more. Several reports also note that electric vehicles won’t go mainstream until 2030, so it is imperative to reduce demand for fossil-fuel powered vehicles in the interim.

Wilf Steimle, president of the Electric Vehicle Society, says there are four pillars that the government needs to address: supply, charging, demand and education. Right now, the government is only focusing on the first two, he says. “There has been very little spent on any government to do broad comprehensive education to make sure everyone understands this technology and why it will save you money and is better for the environment.”

“The dialogue doesn’t stop at manufacturing,” Steimle says.

“I do think that Ford and his government are doing some good things on the manufacturing side. But still, he’s missing half the equation: helping Ontarians actually drive electric vehicles,” Kyriazis says. “Just because you build electric vehicles, doesn’t mean everyone will buy them.”

Right now, 90 per cent of all electric vehicles built in Canada are exported to the United States, while B.C. and Quebec get the bulk of the Canadian supply. The current wait time for an electric vehicle in Ontario is nine to 12 months. Solving the supply-side problem is, as Kyriazis says, half the equation.

That’s why she wants to see the Ford government make a U-turn on a purchase incentive and propose something like a tax credit. She’d like to see provincial investment in charging infrastructure and an electric vehicle mandate in the building code — two things the government scrapped.

“Before the election, I didn’t believe in giving millionaires rebates on over $100,000 Tesla cars. Nothing against Tesla, they’re gorgeous cars. But, you know, I just didn’t believe it. Let’s see how the market dictates.”

Premier Doug Ford

When asked recently if Ford would reconsider electric vehicle incentives, given that the government has in the last two months touted them as the cars of the future, the premier refused to commit.

“Before the election, I didn’t believe in giving millionaires rebates on over $100,000 Tesla cars,” he told reporters. “Nothing against Tesla, they’re gorgeous cars. But, you know, I just didn’t believe in it. Let’s see how the market dictates.”

He added that the government’s approach to electric vehicles is sufficient. “We’re putting billions and billions of dollars into the electric vehicle market in the companies. We’re partnering with the federal government.”

Energy Minister Todd Smith defended the seismic shift in his government’s electric vehicle policy, some of which includes reinstating what it initially cut. In a recent question period, Smith said the electric vehicle charging stations that were ripped up in 2018 were removed because “the equipment the Liberals installed was substandard. It wasn’t working.”

“Nobody was using it,” he said. “We’re going to put in world-class technology thanks to our partnership with Ivy Charging Network … that people are actually going to want to use.”

Opposition parties, however, disagree and are making electric vehicle offerings that could turn it into an election issue next year. The Ontario Liberals have proposed an $8,000 incentive on the purchase or lease of electric vehicles, if they take power, as well as a $1,500 rebate on the purchase of home electric vehicle charging equipment.

The NDP plan includes setting a province-wide zero-emission vehicles sales target of 15 per cent by 2025, rising to 45 per cent by 2030 and 100 per cent by 2035. Their plan promises “strong incentives” for zero-emission vehicles; no dollar amount is provided.

The Greens pledge to “increase access to electric vehicles (two-wheeled or more) and make them less expensive than fossil-fuel powered vehicles, through [incentives], rental systems, financing, and a zero emission vehicles mandate.”

Both the NDP and the Green Party also have extensive proposals to boost Ontario’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure at public buildings, private homes and multi-unit buildings, workplaces and on highways, and to reinsert electric vehicle charging infrastructure into the building code for new construction.

Ontario Greens leader Mike Schreiner considers the Ford government’s shift on electric vehicles a win, noting he has “pushed them hard publicly and privately.” He says these actions, however, “fall far short in terms of what’s needed for widespread adoption.”

“While not being actively hostile to electric vehicles is welcome, their strategy is wholly ineffective because rebates are the most effective way to drive down costs,” he says. “Their plan is reactionary and insufficient.”

At the moment, much of the gap in the electric vehicle space left by the provincial government has been filled in part by the federal government in the form of rebates and funds, as well as policies put forward by municipalities. This month, the City of Toronto released a climate plan that aims to reach net-zero emissions by 2040. The plan proposes that electric vehicles should account for 30 per cent of all registrations by 2030 and aims to deploy over 3,200 fast charging stations in high-priority public locations and create incentives for installing stations in existing buildings. The city also recently passed a bylaw requiring that all new parking stalls include electric vehicle chargers. Other municipalities across the province are following suit as the federal government also looks to impose a national mandate on electric vehicle sales by the end of 2022.

Looking ahead, a big challenge for the Ford government will be figuring out how to respond to the U.S. government’s proposal to implement an electric vehicle tax credit that will offer up to $12,500 to purchase American-made electric vehicles. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the U.S. electric vehicle tax credit is “going to undercut well-established systems and supply chains” across the continent, and indicated Canada could “align” its own electric vehicle incentives to promote buying Canadian. Automotive vehicles are Ontario’s top export item, and Canada’s second-largest; 93 per cent of all vehicles made in Canada, most in Ontario, are exported to the U.S.

Brendan Sweeney, managing director of the Trillium Network for Advanced Manufacturing, says the U.S. tax credit is an opportunity for the federal government to build “a pan-Canadian electric vehicle industry” that will allow provinces to collaborate and join in. “Automakers need government help to build an electric vehicle industry to scale,” Sweeney says. “In the next five to 10 years, if we want this to happen, we all have to be tangled in this.”

He says automakers looking to build electric vehicles will seek out “the most hospitable ecosystem” that will help them sell electric vehicles, which are not yet easily profitable.

“This is an all hands on deck situation,” Klezmer says. “We’ve got huge investments to make in a really small period of time in order to capture the economic opportunities and to meet our climate targets. So definitely the private sector needs to play a role, but we’re finding that in order to do that, a lot of those investments need to be unlocked through a favourable policy landscape.”

Kyriazis agrees. “If the election is causing the Ford government to be thinking about and talking about electric vehicles more, then that’s great,” she says. “But let’s actually propose meaningful actions and not pretend that helping manufacturers to make [electric vehicles] is also going to help Ontario residents to afford them and access them and benefit from them.”

Updated Dec. 16, 2021, at 7:28 p.m. ET: This article was updated to correct a photo caption that had incorrectly identified a Magna executive as company founder Frank Stronach.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits