Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Public servants warned an Ontario cabinet minister last year about a “high-risk” loophole in mine safety rules that required “urgent attention” to avoid environmental disaster, an internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows.

One year later, it appears the politician who received the warning, Ontario Minister of Mines George Pirie, did not act on the bureaucrats’ advice.

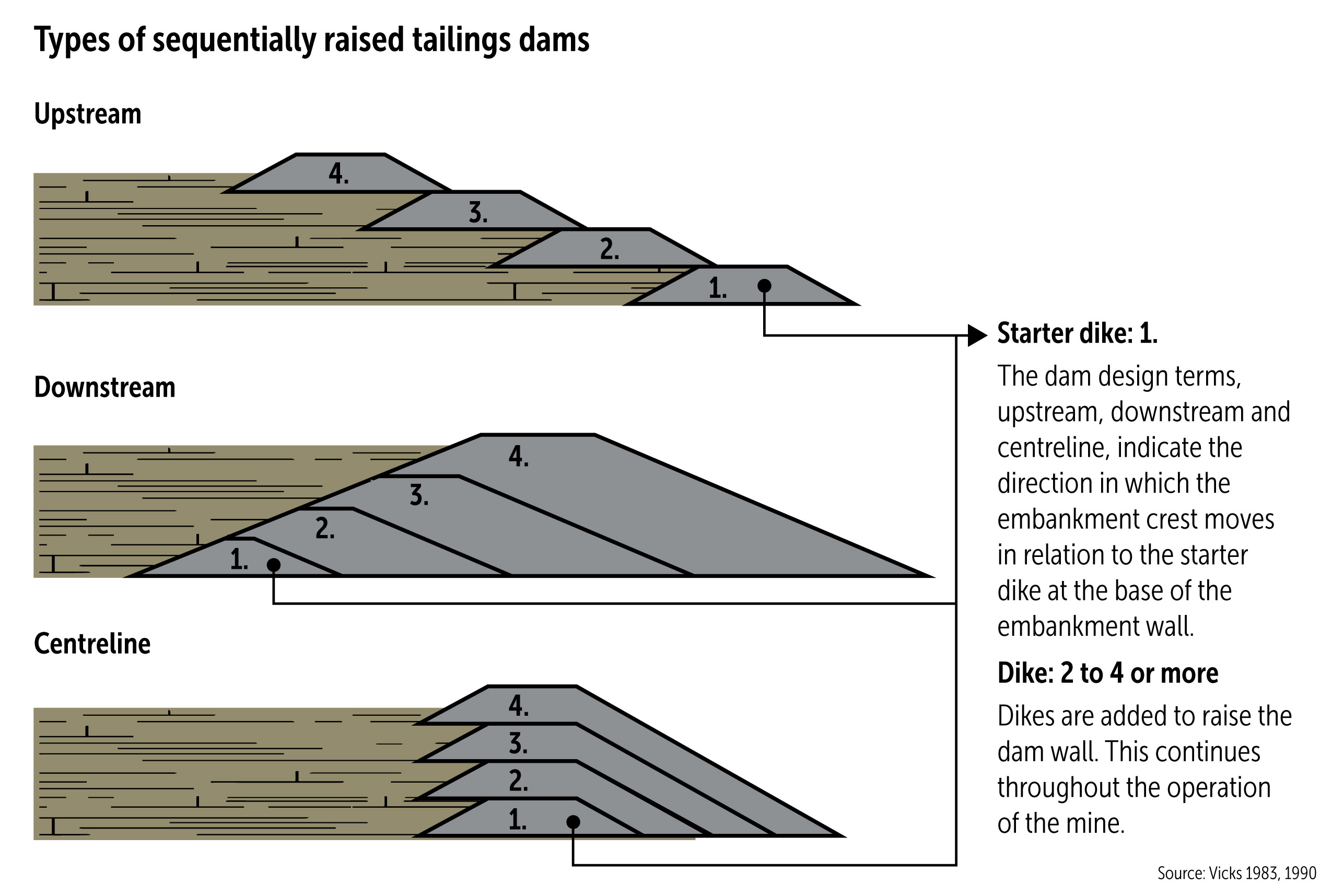

Mine waste, called tailings, is often stored in human-made facilities that those in the industry call ponds. When the dams that hold tailings fail, the consequences can be catastrophic: waterways that were nearly destroyed after the 2014 Mount Polley tailings disaster in British Columbia will need decades more to recover, and the 2019 collapse of a dam in Brazil killed 270 people. Because of the high risk associated with tailings dams, many jurisdictions around the world have rules targeted at keeping them safe.

In Ontario, however, successive governments have not fixed a gap in the province’s tailings dam rules despite being aware of it since 2017, according to the internal briefing document prepared for Pirie in June 2022 and released through freedom of information legislation. Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government has been in power since 2018, preceded by the Liberals under Kathleen Wynne.

The province does have a law covering what are known as online tailings dams — those that are connected to existing lakes, creeks and rivers — which the Ontario Mining Association says make up a small number of the tailings dams in the province. But senior bureaucrats raised concerns that Ontario doesn’t have adequate oversight of the rest, which are called offline tailings dams, the briefing note says.

“Several tailings dam failures have stressed the need for appropriate oversight of tailings facilities,” said the document, part of an orientation binder given to Pirie shortly after he was sworn in as minister.

“In response to these failures, other jurisdictions have reviewed their approach to regulating tailings dams. There is little to no legislative authority to prevent similar situations from occurring in Ontario.”

The gap is outlined in a section of the binder dedicated to “critical decisions” to be made within Pirie’s first 30 days as minister. It noted concerns from senior bureaucrats, who told Pirie the hole in offline tailings dam rules was a “high-risk gap in the regulatory framework that requires urgent attention.”

A spokesperson for Pirie’s office, Dylan Moore, confirmed receiving questions from The Narwhal about the briefing document on July 11 and said the government was working to answer those questions on July 13. However, the minister’s office failed to follow through over the following week, providing no response to subsequent emails sent by The Narwhal on July 14, July 18 and July 20.

Before becoming a politician, Pirie spent 35 years in a variety of senior roles at mining companies, including stints as president and CEO of Placer Dome Canada, Breakwater Resources and San Gold.

The office of Northern Development Minister Greg Rickford, who oversaw mining from 2018 to 2022, did not respond to a request for comment. Nor did past Liberal ministers: Michael Gavelle, who held the position in 2017 and 2018, didn’t respond to a message sent on LinkedIn, while former MPP Bill Mauro, who had a brief tenure as interim mining minister in 2017, did not answer an email. Former premier Wynne said in an email that she did not recall discussions about the issue.

Steven Emerman, a U.S.-based geophysicist and mining expert, said the document obtained by The Narwhal raises serious questions about how the Ontario government has been evaluating the safety of offline tailings dams up until now.

“I think anyone would say this is an urgent issue,” he said.

The briefing document obtained by The Narwhal did not explain what exactly the gap in the rules entails.

The Ontario government publishes very little information about how its tailings management regime works in practice, and how they might be enforced, so it’s unclear what the process looks like or how effective it is. Pirie’s office did not answer questions from The Narwhal about how the government currently approves tailings dams and ensures they are safe.

Ontario does have some oversight of offline tailings dams: the Ministry of Mines inspects them for safety, and requires companies to submit detailed information about how tailings are stored as part of an eventual mine closure plan, which is required before a project can be approved. Companies are required to rehabilitate land after mining and put up various forms of financial assurance meant to cover the costs of that cleanup.

Ontario’s mining law also mandates that tailings be “maintained in a stable and safe condition,” but doesn’t include specifics. Other jurisdictions have detailed design standards for how tailings dams should be built and maintained, but Ontario only appears to have such precise requirements for online dams.

Chris Hodgson, president of the Ontario Mining Association, which represents mining companies in the province, said he was unaware of the regulatory gap described in the briefing note.

“If that’s the case, that’s news to our members,” he added.

Hodgson, a former Progressive Conservative MPP who was minister of mines from 1995 to 1999, also defended the existing Ontario regime, saying he believes the province’s safety standards are among the best in the world.

“[The Ontario government wants] to make sure that our companies are adhering to the best practices, and that that’s enforceable, and there’s good oversight on that,” Hodgson said. “That protects our shareholders as well as the public.”

![A page of a document that reads: Minister's Orientation Binder — June 2022. Contact: Mary Perry, A/Directior, Mines and Minerals Division. Approved by: Afsana Quereshi, A/Assistant Deputy Minister, Mines and Minerals Division. Week Three: Tailings Dam Regime and Discussion with the Ontario Mining Association. Issue: Seeking Minister's approval to consult with the Ontario Mining Association (OMA) on Ontario's proposed approach to the regulation of mine tailings dams. Current status and critical date: In 2017, the then Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry updated its Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act Administrative Guide to provide clarity, stating that "offline dams" do not require Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act approval, resulting in a lack of regulatory oversight over the construction and modification of offline tailings dams in the province. Several recent tailings dam failures have stressed the need for appropriate oversight of tailings facilities. In response to these failures, other jurisdictions have reviewed their approach to regulating tailings dams. There is little to no legislative authority to prevent similar situations from happening in Ontario. The ministry has developed an approach for the regulation of tailings dams and outlined proposed policy components. A decision is required within 30 days to begin engagement with the OMA to collect early feedback on the ministry's proposed approach, so that changes can be implemented as soon as possible to mitigate against potential risk posed by tailings dams' breaches or failures. Options: [redacted] Recommendation: [redacted]](https://thenarwhal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/ONT-MinisterofMines-orientationbinder-tailings.png)

Ontario does not publish data about offline tailings dams specifically, so it’s not clear how many are in the province. But the Ontario government oversees 400 privately owned tailings dams, both online and offline, according to a 2022 report from the province’s auditor general. That’s more than double the number in B.C.

In northern Ontario, tailings dams are scattered across the landscape and often close to communities. Sudbury, for example, has multiple tailings dams near where people live, according to a map published by the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum.

Jamie Kneen of the non-profit MiningWatch Canada said the problem outlined in the briefing document is “concerning.”

“The fact that there hasn’t been a major problem is more good luck than good management,” he said.

“The risks are there, and they increase over time as more tailings dams get built, but also the existing ones get older. If they’re not being properly built and maintained, the chances of something falling apart goes up.”

Tailings are a noxious mix of water, leftover metals, chemicals used to process material extracted from mines and ground rock. Different types of tailings come with different types of risks. But in general, it’s not good for people or the environment when they spill.

Although Ontario hasn’t had a high-profile spill like the Mount Polley disaster, accidents do happen. The 1990 Matachewan tailings spill dumped 150,000,000 litres of heavy metal-packed sludge into the Montreal River north of Sudbury. The plume travelled about 150 kilometres downstream towards Lake Timiskaming and contaminated drinking water in the area with lead.

Another northwestern Ontario mine reported a tailings leak in 2006, although the company said it was able to contain the waste before it reached the surrounding environment. More recently, in 2019, the Ontario government fined mining company Goldcorp $34,650 for spilling a tailings slurry that included cyanide into the South Porcupine River east of Timmins. Seepage from one Sudbury-area tailings pond has been found in nearby Meatbird Lake, which was a recreational area until the mining company bought it in 2021.

It’s important that governments regulate tailings dams because mining companies can often be more motivated to cut costs and maximize profits than to improve safety, said David Chambers, a U.S.-based geophysicist and mine expert who is the founder and president of the Center of Science in Public Participation.

“I’m sorry, that’s just the nature of the beast,” Chambers said. “There are too many incentives and opportunities for things to go wrong.”

In Canada, different levels of government share responsibility for tailings safety. The federal government oversees uranium tailings, for example, and might review other types of tailings dams if mining projects are subjected to a federal impact assessment. Some federal laws might also be triggered if a tailings dam fails. But most of the responsibility falls to provinces, which are responsible for writing rules to govern general dam and tailings safety.

The June 2022 briefing document obtained by The Narwhal said staff at Ontario’s Ministry of Mines had already written a proposed policy to address the gap in tailings rules, but Pirie’s approval was needed to move it forward. The document didn’t spell out what the proposed policy would be, only that the ministry was planning to regulate all tailings dams — offline and online — under a new, comprehensive set of rules.

The first step, the briefing document said, was to get early feedback from the Ontario Mining Association, “so that changes can be implemented as soon as possible to mitigate against potential risk posed by tailings dams’ breaches or failures.”

It’s not clear what’s happened in the year since then. Ontario’s Environmental Registry, where the government is required to post notice of changes to environmental rules, does not show any recent updates to tailings dam policy. Ontario Mining Association’s Hodgson told The Narwhal the Ministry of Mines never reached out about any proposed changes to tailings dam rules.

The Ontario government did overhaul the province’s mining law this year. But the changes didn’t alter tailings dam guidelines: some were aimed instead at moving applications to open new mines through the system quicker, a key strategy for the Progressive Conservatives, who are looking to boost extraction of certain minerals. Other changes to the law made it easier for companies to go back and recover and sell minerals from old tailings.

The former Liberal government created the policy gap in 2017 as part of a move to support businesses called the “red tape challenge” according to an archived provincial document. To “simplify and streamline” the dam permitting process, the Liberals made it clear that offline tailings dams were not subject to Ontario’s main dam safety law — The Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act, overseen by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

The idea at the time, the document said, was to “develop a short term transition plan” to move oversight of offline tailings dams to the mining ministry.

Since then, the Ontario government has been overseeing offline tailings dams using an “interim approach” it did consult the mining association about, the briefing note obtained by The Narwhal says.

That interim approach appears to include a regulation with a section about tailings dam safety, which was updated in 2019. Instead of setting firm requirements, the regulation says people involved in designing, building and maintaining tailings dams should “give due regard” to 11 guidance documents published by the Canadian Dam Association, a group that includes dam owners, operators, regulators, consultants and academics.

The list of 11 Canadian Dam Association guidance documents does not include the association’s most recent advice on tailings dam risk analysis, published in 2021.

Experts and critics consulted by The Narwhal said the current rules likely aren’t strict enough.

Emerman said he’d be a “little hesitant to have full confidence” in a dam constructed under a safety regulation that says to give “due regard” to best practices.

“What exactly does due regard mean?” Emerman added. “Due regard seems to have no enforcement mechanism.”

“I think the Canadian Dam Association is a reputable authority, but if all you’re doing is paying due regard to it, that’s pretty meaningless,” Kneen said.

The Ontario Mining Association provided The Narwhal with a second provincial government document, a 2020 guide titled “Closure Plan Requirements and Best Practices for Tailings Dams and Other Containment Structures.” The guide — which the government has not posted publicly and did not respond to questions about — outlines the types of information companies should give the government to satisfy the “due regard” requirement, like design drawings and reports signed off by qualified engineers.

Hodgson said the Ontario Mining Association worked with the previous Liberal government to develop the current regime and “got it in a pretty good spot in terms of protection for the public and the environment.”

In at least one case, the Ontario government does appear to have used some kind of enforcement mechanism: the 2022 report from the Auditor General noted an instance when ministry inspectors discovered an issue at a tailings facility that “posed a significant risk of failure” and the government ordered the mine’s owner to fix it. It’s not clear how often the government might issue such orders.

The government aims to inspect mines every five to 10 years but often doesn’t complete the inspections on its to-do list, the Auditor General’s report found. As of 2022, the government had not inspected nearly half of Ontario’s operational mines since 2011.

Though the government’s 2020 guide does ask companies for good information, Kneen added, the fact that the document isn’t available to the public makes it difficult to know whether Ontario is actually holding companies accountable.

Ontario’s rules also leave out principles from the 2020 Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management, Kneen said. The standard was developed by a worldwide expert panel convened by the United Nations Environment Programme, among other groups, to prevent catastrophic tailings dam failures.

Emerman said that although the government’s 2020 guide asks companies to submit information and design drawings, it doesn’t say anything about how or the government assesses the content of them. The guide also calls for the approval of the engineer of record, or the engineer in charge, but that person could be a mining company employee, Emerman said. “I don’t find this very comforting,” he added.

Chambers said that if companies were to strictly follow Ontario’s tailings dam safety guidance, as laid out in the 2020 guide and the regulations, they’d “effectively be following best practices.” The problem, he said, is that the wording of the guidance appears to make it voluntary, which means there’s very little the government could do to prevent companies from bending the rules.

“Many regulatory agencies give mining companies the benefit of the doubt, until something goes wrong,” Chambers said.

“Said another way, it usually takes an accident or a bankruptcy to make regulators move from voluntary to mandatory compliance.”

Chambers also said that while the dam association’s guidelines are good, they’re intended as recommendations that complement provincial law, not a binding safety code. “They’re well thought out, but somebody needs to go a step further,” he added.

For example, Chambers said, B.C.’s rules contain guidelines for how steep a dam embankment can be, a level of detail that’s absent from the dam association’s guidelines and Ontario’s offline tailings dam rules. B.C. tightened up its laws after the Mount Polley spill, but critics say they still don’t go far enough. And nine years later, with contaminated sludge from the disaster still lining the floor of nearby Quesnel Lake, the Mount Polley Mine has re-opened.

The Canadian Dam Association, which did not respond to a request for comment from The Narwhal, says on its website that it does not regulate dam construction or engineering.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits