A massive Rockies real-estate project wins another court battle. Opponents will keep fighting it

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

A year after being named Ontario’s first standalone minister of mines in 50 years, George Pirie is consolidating authority over his ministry. In March, Pirie, the former mayor of Timmins, Ont., introduced Bill 71, the Building More Mines Act, which hands Pirie decision-making powers over exploration and mine closures, once relegated to staff.

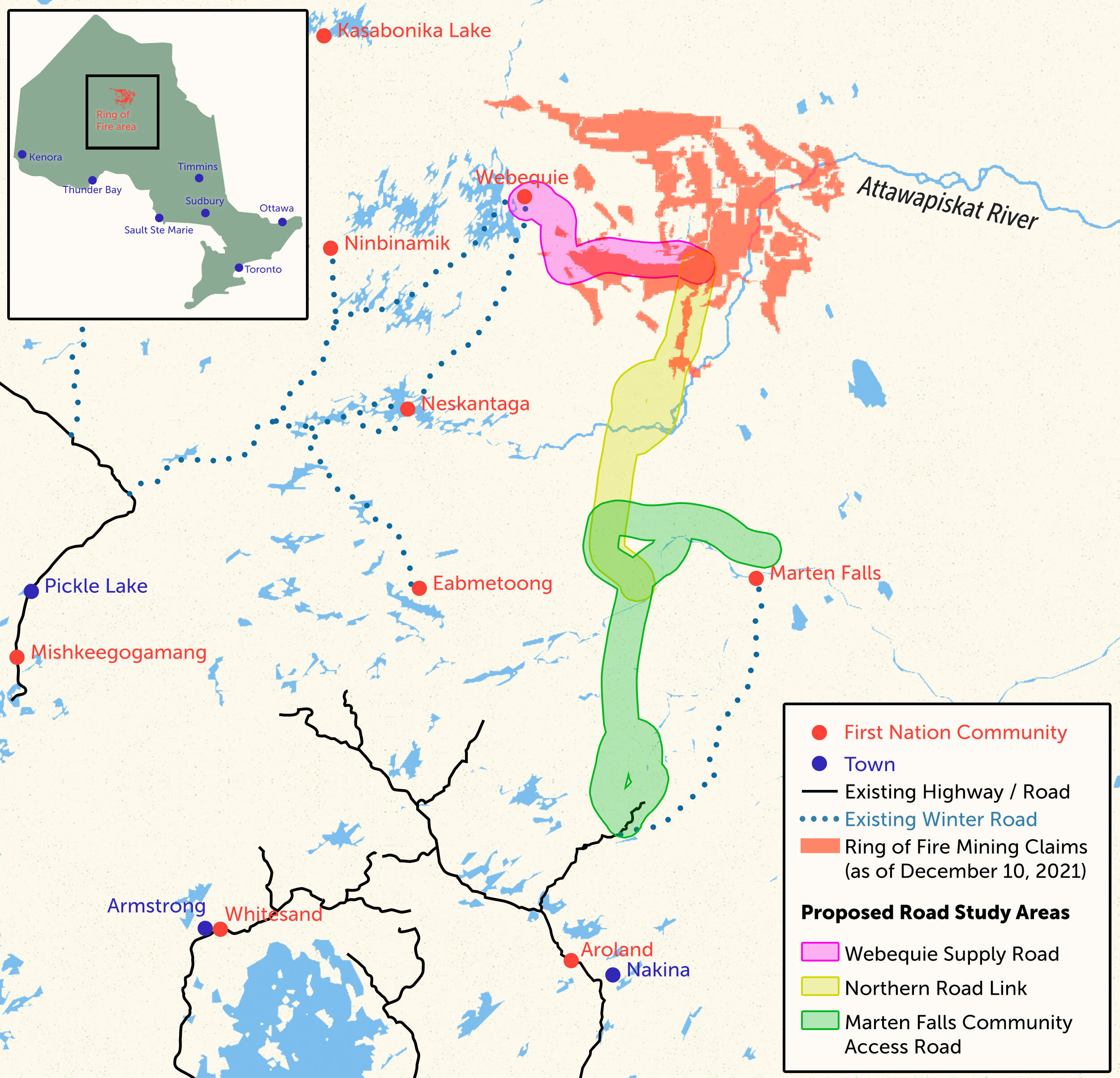

A 35-year mining industry executive and former president and CEO of Placer Dome Canada, Pirie has been tasked by the Doug Ford government to encourage mining in the province; notably in the northern Ring of Fire region, amid growing demand for critical minerals such as nickel, cobalt and lithium, seen as crucial for the battery building needed to transition away from fossil fuels towards electrification.

The act, which received royal assent in May, is currently undergoing public regulatory consultations as to how to put the legislation into effect. But Bill 71 faces criticisms from First Nations, non-governmental organizations and legal experts who say the minister has given himself too much authority over mine exploration and closures that should remain in the hands of technical staff.

“I think it gives a heck of a lot of power to the minister — and much unfettered discretion,” says Elizabeth Steyn, assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s law school teaching a course on critical minerals, regulatory frameworks and geopolitics.

The ministry did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions about Pirie’s technical expertise or whether the minister would receive technical briefings and recommendations from staff prior to making decisions on exploration and closure plans.

There’s also the issue of the province’s duty to consult First Nations, with some Indigenous communities also displeased the act broadens requirements on everything from closure plans to financial assurances to cover the expenses of the closure. Bill 71 cuts off their access to information, they say, making First Nations wary of allowing mining in their territories despite potential economic benefits.

The legislation “just adds to the fear, it adds to the distrust that’s already there,” says Lawrence Martin, director of lands and resources at Mushkegowuk Council, which represents eight Cree communities along the James Bay coast. “It’s disrespecting everything that the people want to believe in the government to do, to help out with. But every step of the way, this gives them another reason to point out: ‘There we go again, we’re about to get screwed again.’ ”

Among the most significant changes Bill 71 makes to the Mining Act is a provision that takes power away from two non-political staff and passes it on to Pirie. The bill would “permit the minister to exercise any power and perform any duty of a director of exploration ” — who oversees mineral exploration and permitting. The act also moves to “remove the position of director of mine rehabilitation” — which is to oversee the closure of mines and recovery of minerals from tailings and waste — and transfer this position’s decision-making authority to the minister.

The two director positions are responsible for the beginning and end of the mining life-cycle respectively, and so have conflicting interests, Steyn says.

Steyn, a former director of the mining law, finance and sustainability program at Western University in London, Ont., explains Pirie has centralized the responsibilities of these two positions into one person — himself, as minister.

“The director of exploration wants to see the development happen. The director of [mine rehabilitation] has to deal with the consequences and the fallout. But [the minister is] taking all of the powers and consolidating them onto himself.”

Eliminating the position of director of mine rehabilitation is particularly troubling in the context of remediating and re-mining waste, says Steyn. Mining companies can apply for a permit to recover minerals from tailings, and under the old act, the director of mine rehabilitation granted these permits on the condition the land would be improved with “respect to one or both of public health and safety” following its recovery.

Under the new act, conditions for health, safety and environment must simply be “comparable to or better than it was before the recovery, as determined by the minister.” Steyn notes that not only does the act drop requirements to improve the land’s condition, but it leaves the question of whether the tailings are in a similar state prior to its re-mining up to the minister.

“That’s a heck of a qualification,” she says. “It’s very subjective — it’s in the minister’s opinion.”

The broad standards also concerned Martin. “There’s a Cree word, mamash, which means ‘half-ass’ or ‘haphazardly,’ ” he says. “We can’t bring the land back to the way we found it. That’s understood. But the people don’t want to have it put back in place half-ass, either.”

David Good, a professional geologist and visiting scientist-in-residence at Western University, says “the process of permitting a mine project is lengthy and complex.” Good, who was a former vice-president of exploration for several Ontario mining companies, says the decisions to approve projects are “by definition political, and the minister should have the skill and experience necessary to make such determination.”

The closest global legislative parallel Steyn could think of is in western Australia: there, the Aboriginal Heritage Act of 1972 enabled mining companies to apply to destroy Aboriginal heritage sites, requests which were reviewed by a committee before being decided on by politicians. “That minister basically rubber-stamped every request that came from a mine that affected sacred sites,” Steyn says, including the destruction of heritage sites at Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto in 2020, which caused international outcry.

“Now, fast forward to Ontario, and it’s giving the exact same kind of powers to the minister,” Steyn says. “The potential for abuse is so rife. It’s just unseemly for me in a balanced, democratic sense.”

“We are really dependent on the minister of mines being a very prudent, very wise person — somebody who’s absolutely not biased towards any party.” Steyn says, pointing out [Pirie’s] history as a mining executive. “We don’t have to wonder what camp he is in,” she says. “I’m not saying Minister Pirie will abuse it. But the potential is there.”

Minister Pirie did not respond to questions from The Narwhal.

Under previous legislation, government staff with technical expertise reviewed closure plans to “flag concerns” if mining regulation requirements weren’t met. The new amendments will end that practice, which was put in place upon recommendations from the auditor general in 2015. Instead, “qualified persons” outside the government will be allowed to perform a review — while policy is being drafted to define just who is a “qualified person,” the ministry is currently proposing it be someone “authorized to practice in Ontario in the areas of engineering, geoscience, agrology or landscape architecture,” limited to “the scope of [their] professional practice.”

This, Steyn says, means a mining company’s staff or hired consultants could be the ones reviewing closure plans. “Basically, you’re letting the mine sign off on their own closure plan. There’s no external review,” Steyn says.

Good says, however, industry engineers, geologists and other “qualified persons” will be both trained and experienced, and “all of them take this responsibility very seriously. Nobody will risk their reputation or livelihood on shoddy or incomplete work.”

Steyn points out though, in a volatile industry dependent on significant capital financing such as mining, “people get under extreme pressure from bad operators. If your boss says to you, ‘Sign on the dotted line or we are going bankrupt because we can’t keep raising financing,’ some people will cave under pressure.”

Industry malfeasance is an exception, not a norm, Steyn says. “I’m not saying this will happen in every operation,” she says, adding “we only need one Mount Polley, one Brumadinho mine disaster.”

Such disasters, Good says, are “the hammer over the head” of every qualified person. “The mining industry is populated by many professionals with impressive records and the technical expertise to prepare closure plans,” he says. That said, he believes these plan assessments should be made public through environmental review processes. “Nothing would or should be hidden,” he says.

First Nations have highlighted several issues in the Building More Mines Act, saying the legislation fails the government’s duty to consult affected Indigenous communities. For example, the legislation enables what the ministry calls a “conditional filing order,” which would allow the mining minister, at a company’s request, to approve an incomplete closure plan “that does not contain all regulatory requirements,” with stipulations to complete unfinished elements of the plan at a later, specified date.

Mushkegowuk Council released a public response to the act in April: it states that the use of a conditional filing order “would force First Nations into consultation on mining proposals with no clear assurance the impacts of the project would be adequately remediated. Such a scenario makes free, prior and informed consent an impossibility.”

The act also loosens the requirements for companies to notify the ministry if plans for a mine change. Under old legislation, companies had to file a “notice of material change” to the director of mine rehabilitation if a project was altered or expanded, switched ownership or if “any other material change has occurred” that could affect the closure plan. If the director of mine rehabilitation position is eliminated, the mining minister will oversee a truncated change notification process.

Under the Building More Mines Act, companies will only have to file a notice of material change if changes “could reasonably be expected to have a material effect” on the closure plan. ”

In April, Jordan Benoit, policy manager of the territorial planning unit for Grand Council Treaty #3, which represents 28 Anishinaabe communities in northwestern Ontario, wrote the Mining Ministry with a number of criticisms of the bill, including this elimination of most change notices: “This proposed amendment may let important [notices of material change] ‘slip through the cracks’ and not receive proper consultation. First Nation communities need to assess a [notice of material change] themselves … .”

This move also empowers Pirie, Steyn says, as the act now allows the minister to determine what constitutes a material change, “because everything is done by the minister.” Material changes of any kind should be evaluated “in the objective sense of the word, not the watered-down, ‘discretion of the minister’ version that we have here,” Steyn says. “There should be ongoing consultation between a mine and its stakeholders. This is international best practice.”

“It behooves any responsible and prudent mining operator to follow international best practice rather than just to scrape by the provisions of the lowest denominator law,” Steyn adds.

Jordan Hatton, director of economic development at Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek, says his nation on Lake Nipigon, north of Thunder Bay, “is a very pro-development community.” After pushing Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek off its land to build dams and provincial parks, Canada only granted the nation reserve land in 2010.

“We’re trying to rebuild from scratch,” Hatton says, adding the community has industry partnerships and agreements with companies such as Rock Tech Lithium and Imagine Lithium.

Even so, Hatton says, the Ontario government’s loosening of mine requirements on everything from closure plans to financial assurances is “not going to build support among the Indigenous population in the membership of our First Nation or other First Nations.” He believes Bill 71 is “probably going to harm” the development of future mining projects more than help it.

Martin, of Mushkegowuk Council, says the legislation is “not a good way to sell this mining [to the region],” he says. “If people were able to feel any kind of comfort to accepting a mine, if they could see the proper, responsible way of setting up these processes, it would not be so bad.” He says communities at the southern end of James Bay are already coping with the aftermath of abandoned mines in their region; to the north, the most infamous case is Attawapiskat First Nation, which continues to deal with fallout from the Victor diamond mine run by De Beers, which failed to monitor mercury levels that seeped into the local water system.

Hatton, Martin and the public statement by Benoit of Grand Council Treaty #3 all say Indigenous communities do not have the resources to adequately process the exploration agreements and consultation documents sent their way by companies, and to avoid further delays, Canadian governments should provide them more resources to hire staff.

While the act’s changes might seem to save time and money for companies in the short term, Steyn says, potential legal challenges from Indigenous communities and non-governmental organizations could cause more delays in the long run.

“I can assure you that a contested project takes a heck of a lot longer and can drain a fortune,” she says, adding she attempts to “walk a balanced line” considering the needs of Indigenous communities, non-governmental organizations and industry. “I’m all in favour of getting critical minerals, but we can’t be irresponsible in how we do this.”

Steyn believes the legislation is a missed opportunity for the government to establish stronger First Nation and other stakeholder engagement.

“I don’t think it will get anywhere,” she says. “There’s simply too much that they are trying to do that’s not within their power.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...