Danielle Smith says separation is about alienation. It’s really about oil

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

For a moment in the glow of a golden summer morning, it feels like White Lake might stretch on forever.

A breeze ripples across the narrows towards the southern end of the lake. Pine and poplar sway at the shoreline, gesturing to inlets and islands as far as the eye can see. On one side sits a provincial park. On the other is Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg, an Anishinaabe community that shares its name with the Anishinaabemowin word for the waters — Netmizaaggamig, the heart of its territory and culture.

But if you look at this place just upstream from Lake Superior on a map of mining claims, it’s hard not to see it differently. A patchwork of squares where prospectors have reserved rights to minerals under the surface blanket the boreal forest and sections of the lake — even most of the sacred narrows, an important travel route for both walleye and Netmizaaggamig people, where there are historic burial sites. Every single claim holds the chance a mining company could, at any time, seek permits to start drilling.

On this expansive landscape that has been their home since time immemorial, Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg and the waters they rely on are quietly surrounded.

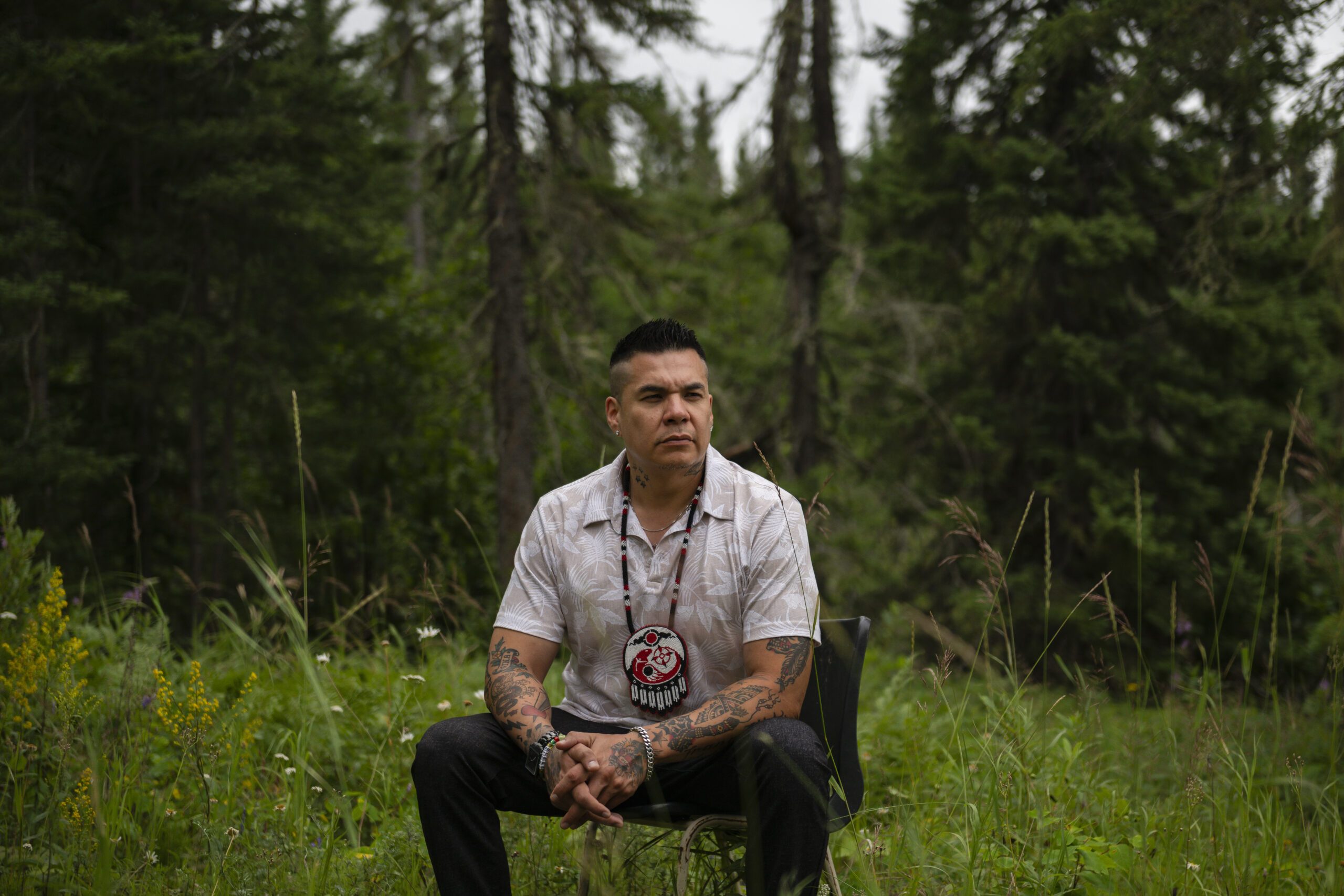

“If mining companies get their way to stake claims on our territory, especially around White Lake, you can pretty much kiss the lake goodbye,” Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg Chief Louis Kwissiwa says.

Northern Ontario’s economy has revolved around resource extraction for more than 150 years, with mining often at the centre, be it nickel in Sudbury or gold in Wawa. But many of the existing mines in the region are older and closer to closure, and for a time in the 2010s, low commodity prices made it difficult for new mines to open. Now, there’s a renewed mining boom underway in northern Ontario, and Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg — formerly known as Pic Mobert First Nation — is among the communities on the frontlines. Much of the boom has been fuelled by Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives, who have been pushing since 2018 to get in on a global rush for the raw materials, also known as critical minerals, needed to build lower-emissions technology like electric vehicles.

Northern Ontario is “largely empty and begging for exploration drill holes,” Minister of Mines George Pirie told NatNewsLedger earlier this year. The statement called back to a time before governments at least paid lip service to the idea of reconciliation, echoing the false idea that land in Canada belonged to no one before European settlement, which was used to justify the seizure of Indigenous land.

The province’s public focus so far has centred on the Far North Ring of Fire, a remote region of environmentally sensitive and carbon-rich peatlands. Politicians and miners have tried and failed to access unproven mineral deposits there for more than a decade. But farther south, there’s plenty left in the ground that’s easier to get to, and the Ford government — especially Pirie, a former mining executive who represents the riding of Timmins, just east of Netmizaaggamig — has thrown its support behind accelerating mining here as well.

Companies have responded to the Ford government’s overtures by staking even more claims, like those around Netmizaaggamig. And it seems every few months, headlines in northern Ontario are abuzz with a new proposal or ribbon-cutting ceremony.

For some northern communities, the prospect of a mining resurgence is a lifeline as other big employers, like pulp mills, have shuttered. New projects could breathe fresh life into struggling resource towns — and advocates say some companies are doing it more responsibly than in generations past.

In Marathon, about half an hour down the highway from White Lake, another Anishinaabe nation, Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, is on board with a new palladium and copper project on their territory. It took years of negotiation between the nation and Toronto-based company Generation Mining to get there: “We fought long and hard … to get an agreement that was worthwhile to us,” Biigtigong Chief Duncan Michano says.

But not every company has prioritized First Nations’ consent — and the Ontario government doesn’t require them to. Often, it puts the onus of the government’s constitutional duty to consult First Nations on private, for-profit corporations. That means the promises and perils of a new generation of mining can play out differently in communities just a few minutes apart.

Indigenous Rights in northern Ontario have been braided together with mining for more than 150 years. Resource extraction is a major reason many nations in the region have a treaty at all.

In the 1840s, as would-be miners streamed onto the American side of Lake Superior in search of copper, the British colonial government on the north side started wondering if there might be some beneath their feet too. The land belonged to Anishinabek, or Anishinaabe people. Crown governments had no authority to give it away. But officials issued the first mineral exploration permit in 1845 anyway, and the following year, leased land on Lake Superior’s Mica Bay to a mining company.

Anishinaabe leaders confronted the government about its seizure of unceded land, calling for the miners to leave, or for a treaty that would allow their communities to share in the profits of resource extraction in their territories. Crown representatives didn’t actually agree to one until 1849, when three Anishinaabe chiefs, fed up with threats and inaction, led a group that seized the mine at Mica Bay, forcing the company to shut it down and the government to come to the table. The result was the Robinson Treaties of 1850 on lakes Huron and Superior, named for the Crown negotiator William Robinson.

Nowadays, the upper Great Lakes are dotted with the remnants of old mines and the makings of new ones, on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border.

Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg and its neighbours, Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, are among the half-dozen First Nations in the region that didn’t sign the Robinson-Superior Treaty in 1850, and are still negotiating title claims with the province and Canada. Governments have seized their territories anyway. The federal government built prisoner of war camps around White Lake during the Second World War, and the Ontario government established White Lake Provincial Park across the water from Netmizaaggamig’s reserve in 1963. (The province does not permit mineral staking in the park.) And mines have already been operating in the region for decades.

Band members bought back the first parcel of land that now forms one of two Netmizaaggamig reserves in 1922. The community has fought for every single bit they’ve added since. That process continues even now.

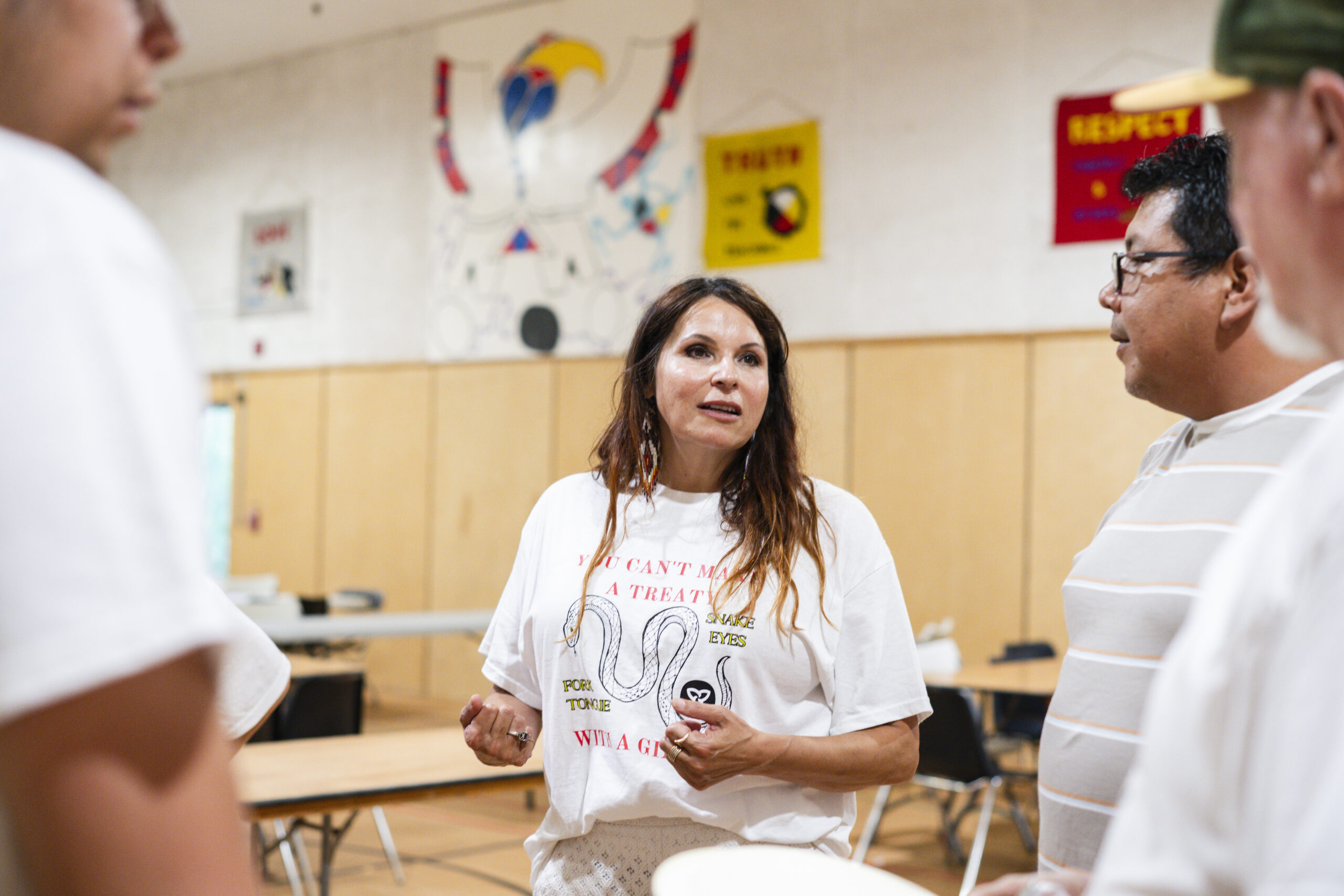

Netmizaaggamig also started formally pushing Crown governments in 1979 to recognize its title claim: to affirm that its members never signed the treaty and have jurisdiction over their territory. Theresa Bananish remembers overhearing adults talking about it when she was a child. More than four decades later, she’s the lead lawyer representing her community in the negotiations that continue to drag on.

“We’ve been here since the beginning,” Bananish says. “Our community has been here. Why is it that the First Nations have to prove their ownership over lands? It should be the Ontario government proving that. Where is your title coming from?”

The community started legal action against Canada and Ontario in 1984. Discussions moved out of court in 2016, with negotiations continuing to this day. While they’ve played out, Ontario has overhauled a major portion of its mining system, despite the vast implications for the land at the centre of the title claim.

Up until 2018, prospectors who wanted to claim the rights to look for minerals in a certain area had to hike in and drive a stake into the ground. That year, Ontario unveiled the Mining Lands Administration System, or MLAS. All of a sudden, anyone could pay a small fee to register a claim online. The system was designed under the previous Liberal government but rolled out by the Progressive Conservatives.

Ontario doesn’t require prospectors to consult First Nations about claims on their land, and in the past few years, there has been a tidal wave.

For Netmizaaggamig, that intensified after the Ontario government highlighted deposits within the nation’s territory in its 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy. Netmizaaggamig territory alone — which encompasses a vast area stretching north from Lake Superior to White Lake and beyond — had 9,679 active mineral claims as of Dec. 13, 2024. Of those, 5,318 were staked after the new system went online.

Ontario placed a “notice of caution” in the online claim system in December 2020, a buyer beware-style bulletin warning prospectors that a large area of northern Ontario may be subject to First Nations’ title claims. But prospectors are still allowed to register claims almost anywhere in Netmizaaggamig territory, right up to the boundaries of its reserves.

Netmizaaggamig and Biigtigong issued a public warning of their own in April 2024, mapping out areas of special cultural value where the nations won’t allow any type of mining activity. Ontario’s unwillingness to block claims in those areas in the first place “has resulted in mining companies spending time, money and effort on projects that will not have First Nations support and that will not advance,” the communities said in a joint statement. Though pushback from First Nations isn’t always enough to stop the Ontario government from approving mining-related permits, some nations have also used the courts to fight against them.

“The communities support mining in their territories where it is appropriately located, where environmental impacts have been minimized and mitigated, and where there are direct benefits to the communities,” the statement from Netmizaaggamig and Biigtigong said.

Across the province, other communities are drowning in claims too. So many that the Chiefs of Ontario, a group representing all 133 First Nations in the province, called on the Ford government last January to pause all mining claims for a year. Pirie did not grant the request.

Similar claim staking systems have led to a wave of legal challenges across Canada. Yukon’s appeal court affirmed Indigenous Nations must be consulted on mining claims more than a decade ago. In British Columbia, a mining claim system a lot like Ontario’s is now being overhauled after a 2023 court ruling that the process violated Indigenous Rights. The Quebec government is appealing a parallel decision its Superior Court made in October 2024. Two separate lawsuits — one filed by Asubpeeschoseewagong Anishinabek, or Grassy Narrows First Nation, and another by six far northern nations — are now seeking similar judgements in Ontario.

But as those processes play out, the claims remain.

Just half an hour away from Netmizaaggamig, both the town of Marathon and Biigtigong Nishnaabeg are sorting through ways to avoid repeating the mistakes that came with the last generation of mines.

Biigtigong is a hub of activity, humming with new construction as it prepares for the Generation Mining Marathon Palladium-Copper project. The nation, a stone’s throw from town, has 1,200 members, of which about 500 live on-reserve. For many years, it has been partnering with industry and negotiating benefits agreements that have fuelled its growth.

The terms of the nation’s final benefits agreement with Generation Mining are confidential, but Biigtigong hired its own experts to ensure the project met strict environmental standards. The deal also includes revenue for the First Nation and jobs for its members.

A lot of those members work at the nearby Barrick Hemlo mine just down the road, but will need other jobs when it eventually closes, Chief Michano says. “They’re good-paying jobs. You drive around the community, you’ll see RVs in almost every driveway, sometimes two cars, [all-terrain vehicles] … Where are our people going to work in the future? We need to think about those kinds of things.”

Marathon Palladium-Copper passed a joint review from the provincial and federal governments in 2022, and has nearly all of the permits it needs to begin construction. Generation Mining has said it hopes to get started in 2025. In the meantime, a new mine comes with heaps of preparations for the communities around it. A burst of new economic activity tends to draw new residents — about 1,000 people will be hired to build the mine over the course of two years. Once it’s operational, around 400 people will have jobs at the facility, which is expected to produce ore for more than a decade. (Generation Mining initially agreed to an interview with The Narwhal about the project, but was not available by publication time.)

Many workers will live in a camp between Marathon and Biigtigong. The First Nation also expects members who have moved away might return home to work at the mine — and it’s trying to get ready for them. Biigtigong’s housing is at full capacity and the nation needs a new water treatment plant to build more, so work on both is underway.

“We had to be mindful of what the impacts this project was going to have on not only today, but the long term, for generations to come,” Biigtigong CEO Debi Bouchie says.

Concerns about how the influx of new residents could affect Biigtigong’s safety also came up during the joint review process: across Canada, evidence has linked camps of transient, largely male resource sector workers to higher rates of violence against Indigenous women. Acknowledging the potential for risk, Biigtigong wants to have a strong social safety net ready. For example, a nine-bed shelter for women and children is in the works.

The plan is to have safe places if and when people need it, Bouchie says.

“I’m not saying they’re all bad, I’m not saying that at all, but you do get a fraction of people that maybe they’re here to make money and that’s it,” Bouchie says, recalling what Marathon was like when she was a teenager during a previous mining boom. “Back in the ’80s … there was racism, there were a lot of those things that were happening. That is absolutely unacceptable to us in today’s day and age.”

Rick Dumas, the mayor of Marathon, has also spent a good chunk of time thinking about how to learn from the mistakes of the ’80s. The town’s government at the time invested a ton of money on infrastructure for the sudden burst of new residents: a town hall, buildings for police and fire services, a ski hill, a library. Much of it was financed with debt Marathon was suddenly unable to pay back a decade later. “I’m not about blaming anyone, just the way it happened,” Dumas says of the former council. “It’s just the boom game.”

“This time, we’re going to be much more planned and more detailed around what we’re going to do,” Dumas says. So far, that has meant housing. The town has opened two residential buildings with a total of 80 units in the last two years, and a site that used to house workers at the long-shuttered pulp and paper mill will soon host a neighbourhood of affordable tiny homes.

“I see the community changing for more stabilization,” the mayor says.

Stability is what Netmizaaggamig wants too — and the right to decide what role mining might play in its future.

“It’s not just about the mining or Aboriginal title claims,” Kwissiwa says. “It’s about the health and well-being of the environment, the health and well-being of the land, the animals, the fish, all of that. … That’s what we’re fighting for.”

Not all mineral claims become mines. But all mines do start out as mineral claims. Usually, small firms called junior mining companies try to find new deposits and figure out if they’re worth digging into. If they hit something good enough, they’ll often sell the asset or partner with a bigger company that has the resources to develop it.

The likelihood of a claim making it to that point is low, so in hopes of eventually hitting a deposit like the copper and palladium near Marathon, prospectors and junior firms often stake a bunch of them. The claim gives them the rights to any minerals that may be underground. It also allows the prospector to construct buildings and apply for early exploration permits that, among other things, let them clear land and drill for samples. The Ontario government nearly always grants early exploration permits, even when they lack the consent of the First Nations whose territories the claims sit on.

On Netmizaaggamig’s territory, southwest of its reserves, the nation is still pushing back against an early exploration permit a company called MetalCorp applied for in 2020. The Ontario government has kept the application on hold ever since “to allow for additional time to adequately consider any concerns.” Netmizaaggamig told the government in 2020 that it would never consent to mining activity in that area. The nation has recorded a total of 325 cultural sites near the company’s mineral claims in that zone. People from Netmizaaggamig use the land to harvest medicinal and ceremonial plants. There are also birth sites, one ceremonial site and places where people camp or have cabins.

Despite this, the Ontario government flagged the spot as a priority location for mineral exploration in its 2022 plan for securing critical minerals. Another mining company, GT Resources, bought MetalCorp and its claims in that zone the following year. And it continues to seek that early exploration permit.

Adding to the tension, Netmizaaggamig and GT Resources are also in the midst of a back and forth over money. When GT Resources — formerly known as Palladium One — bought MetalCorp, it also took responsibility for a memorandum of understanding MetalCorp signed with the nation. Netmizaaggamig says the agreement, inked in 2009, required the company to pay a certain amount per year as long as it held claims on their territory, with the amount increasing if it engaged in exploration work. MetalCorp paid some of that money but not all. Netmizaaggamig says it is still owed more than a decade’s worth — amounting to $216,000 — and terminated the agreement over the lack of payment.

GT Resources has continued to seek permits to do early exploration work on other sites, like one north of White Lake that it received provincial approval for in spring 2024. Netmizaaggamig is continuing to oppose that permit and others, saying it’s not willing to support any applications from GT Resources for early exploration work until the two sides can negotiate a new agreement. And one of the nation’s preconditions is for the company to surrender the former MetalCorp mineral claims, given the cultural importance of the land they sit on.

“We cannot sanction a project where we stand to lose yet again due to Ontario’s racist policies and practices levelled against my nation,” Kwissiwa wrote to the mining minister’s office in a November 2024 letter, copied to GT Resources.

GT Resources did not respond to questions from The Narwhal. Hours after The Narwhal sent the company questions, it notified Netmizaaggamig it would be seeking six more early exploration permits in the nation’s territory, the nation said.

In a December 2024 response to Kwissiwa’s letter, shared with The Narwhal by Netmizaaggamig, GT Resources CEO Derrick Weyrauch said the company has met all of its obligations to the First Nation. Weyrach also said the company has been “unable to obtain the required permits because of [Netmizaaggamig’s] opposition,” and suspended payments to the nation due to a “force majeure” clause in their agreement. Such clauses usually release one party from a contract in the case of a huge and unexpected event, like a natural disaster, that affects its ability to continue work. GT Resources sees Netmizaaggamig’s opposition as that prohibiting factor, the letter said. The Narwhal has not seen the wording of the original agreement.

Though Weyrauch said in the letter that GT Resources is open to negotiating a new agreement with the nation, he said the company can’t agree to Netmizaaggamig’s preconditions and isn’t willing to forfeit its mineral claims.

“The forfeiture of claims has economic and business implications for our company and its investors,” Weyrauch wrote. “It is an extreme measure that seems unnecessary in relation to exploration activities. GT would need to be properly compensated for the loss of any claims and will not voluntarily release those claims.”

Weyrauch said the company offered to work with Netmizaaggamig to identify sensitive areas “so we can plan our work with appropriate care,” and that early exploration work has a “limited and temporary impact on land.” Weyrauch also said the nation’s definition of culturally sensitive areas is so “broad” it would “severely impact GT’s mineral claims.”

Despite the ongoing dispute, the Ontario government has supported GT Resources’ exploration work in the past few years with three payments of $200,000 to its subsidiary Tyko Resources, delivered through a program aimed at helping junior mining companies.

Ontario’s Ministry of Mines did not answer questions from The Narwhal about the permit or the funding it has given to GT Resources.

“The bottom line is, they think it’s theirs,” Kwissiwa said of some mining companies in an interview with The Narwhal. “We were here, we’re still here, we will always be here and they’re not understanding it.”

In the past, when mining claims have overlapped with land Netmizaaggamig sought to add to its reserves, it has had to pay out of pocket to buy those claims out. As Ontario allows mining claims in areas Netmizaaggamig has outlined as part of its title claim, the nation is concerned it may have to buy out even more.

Pirie’s office and the office of current Indigenous Affairs Minister Greg Rickford didn’t answer The Narwhal’s questions about whether the province would be willing to buy out mining claims to resolve Indigenous title claims, and their government hasn’t made any public statements about it. In 2018, Premier Doug Ford ordered his Indigenous affairs minister to “work to resolve land claim issues where possible, but always put the taxpayer first,” according to a mandate letter obtained by Global News.

Netmizaaggamig is open to mining in its territory — it has partnered with industry before and is willing to again, if companies properly consult the nation and propose projects outside of the culturally important spaces it’s protecting, as per its April 2024 announcement. But the process has to happen with the nation’s consent. And while Netmizaaggamig fights for control of its land, it’s also grappling with multiple crises at once, with colonialism at the core: violence, addiction, suicides. A lack of resources to tackle these emergencies is among the reasons other First Nations in Ontario have also called for new mining claims to either be stopped or paused.

Months after The Narwhal visited Netmizaaggamig, a spate of violence drove Kwissiwa to Queen’s Park to ask the Ontario government for help with policing, and with access to mental health and addictions treatment. There were multiple gangs operating on reserve, two stabbing attacks, a home invasion and the beating of a young man who was held at gunpoint. In one incident, police didn’t come for four hours. The nation has paid for private security and mental health support to keep the community safe, accumulating $5 million in debt.

“I stand here today representing a community in crisis, a community that has endured more pain, loss and neglect than any community should ever have to face,” Kwissiwa told reporters at the legislature.

“It is the accumulation of years of systemic neglect, a chronic underfunding of essential services and a lack of action from those with the authority and resources to help.”

Speaking to reporters at Queen’s Park, Netmizaaggamig CEO Joe Moses contrasted provincial funding to boost mining to calls for help with community safety that go nowhere. “People will always want to meet with us when they want to exploit the natural resources,” he said.

Netmizaggamig is in a “painful place” these days, Bananish says. She has been practicing law in Sault Ste. Marie, and for years had only been in Netmizaaggamig for short visits. When she came home for a longer stay last summer, she was shocked to see how much it had changed. There’s no easy way to fix what’s happening now, Bananish says, but it has to start with the community taking control of its own lands and future.

“It’s going to be hard, but the way out is us leading ourselves,” she says. “You just can’t rely on the government.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...