5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Depending on who you ask, mining the Ring of Fire region of Ontario’s Far North could either help save the planet or propel it faster towards climate disaster.

It could shower riches that would boost Ontario’s economy for decades, or end up a boondoggle that never turns much of a profit. And it could offer a wealth of opportunities to First Nations nearby, or it could catastrophically harm their homelands and way of life.

At the centre of it all are the carbon-rich peatlands of the James Bay Lowlands, about 540 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay, Ont., and the unproven mineral deposits that lie underneath. Ontario Premier Doug Ford is seeking to turn the remote region into a mining hub, an idea that was a central plank of his re-election campaign in the 2022 Ontario election.

But there are very huge outstanding questions about the Ring of Fire that probably need to be resolved first. Will the value of the minerals there outweigh the costs of getting to them? Is it a good idea to source materials for clean technology by disrupting a natural carbon sink? What kind of future do First Nations in the region, who have lived there since time immemorial, want for their homelands?

Here’s what you need to know about the Ring of Fire — and the Ontario government’s ongoing push to kickstart mining there.

The Ring of Fire was named after a Johnny Cash song, and the crescent shape of the mineral deposits there, which cover about 5,000 square kilometres. Mining companies first found the deposits in 2007, sparking a blitz of mining claims and rapture over its potential, which has cooled in the years since but never entirely gone away.

At first, companies were excited about chromite, which is used to make stainless steel. But global markets changed over time, and now the focus is more on nickel, which is a crucial part of electric vehicle batteries, a market Ontario Premier Doug Ford is seeking to get in on. He famously pledged in 2018 to make the Ring of Fire happen even if he had to hop on a bulldozer himself — this has not happened to date.

“We have critical minerals that the entire world is after,” Ford told a cheering audience in June 2022, when he was sworn in for his second term. “We’re working with Indigenous partners to build the road to the Ring of Fire, to bring prosperity to northern communities and unlock the full potential of our economy.”

Ford is just the latest politician to jump on the Ring of Fire bandwagon. The idea of mining there has proved irresistible to successive premiers, who have all pushed to make it happen but ultimately failed. At times, the federal government has also been on board: in 2013, then-treasury board minister Tony Clement said it was “no ordinary mine development,” and that it was an opportunity Canada couldn’t afford to let pass by.

For one thing, getting there is far from easy. The region is very remote. It’s only accessible by ice roads in the winter, or by air. There are no permanent roads, which would be needed to make mining happen. The area is also lacking other important infrastructure like transmission lines.

Another key issue is Indigenous consent. Some First Nation governments in the area are in favour of development they say will help their communities, but many others have concerns — more on that later.

Building roads and transmission lines also brings up a whole other set of problems: doing so would disturb sprawling peatlands, part of the world’s second largest complex of wetlands. They store carbon and are tremendously important for wildlife. They’re also very boggy, which makes it difficult and expensive to build anything on top.

In 2019, the Ontario government estimated that road construction there could cost an average of $2.69 million per kilometre, with the entire project taking between $1.1 billion and $1.6 billion.

That price is getting more expensive: it’s now expected to cost over $2 billion, instead of the $1.1 billion to $1.6 billion Ontario proposed three years ago, The Narwhal reported in May 2022.

Which brings us to the question of whether the minerals in the Ring of Fire are worth what it would take to get there — something that isn’t clear right now. Both the federal and provincial governments are internally using estimates of the minerals’ value that are not only outdated, but were also debunked as “nonsense” by the Globe and Mail in 2019, The Narwhal reported in May. Experts question whether mining in the Ring of Fire makes any economic sense: “If it’s such a goddamn good project, why does it depend on massive amounts of government aid?” Patrick Ryan, a consultant with Mining for Facts in the United States, previously told The Narwhal.

Ford and proponents of mining in the Ring of Fire argue that the minerals there could power the push to lower global greenhouse gas emissions — specifically, the manufacturing of electric vehicles. Environmentalists and some First Nations argue the costs of disturbing the region’s peatlands outweigh any possible benefits.

For now, we don’t know what the exact impact of projects in the Ring of Fire could be, because the environmental assessment processes meant to answer that question are still underway. But we do know that disturbing the landscape of the James Bay Lowlands will likely have serious consequences.

That’s because the peatlands there are mind-bogglingly important. In Ontario’s Far North, peatlands store about 35 billion tonnes of carbon, equal to annual emissions from over 39 billion cars. It’s the second-largest intact peatland complex in the world. Mining and the construction of roads and transmission lines would cut through the peatlands, and destroying them releases that carbon to the atmosphere. One study, published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment in 2021, estimated that between 130 and 250 megatonnes of carbon could be released into the atmosphere if all of the peatland in the Ring of Fire covered by mining claims is disturbed.

“[Peatlands] regulate the climate,” said Justina Ray, president and senior scientist of Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, who was a co-author of the study. “It represents up to 10,000 years of accumulated peat, which has lots of carbon.”

The peatlands of the James Bay Lowlands are also home to endangered species like caribou and wolverines, and reams of migratory birds. Northern Indigenous communities have understood their importance since time immemorial: Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation elders call them the “breathing lands.”

At the same time, peatlands are sensitive to disturbances like development. They don’t really recover, either: they take thousands of years to form, growing up to one millimetre per year.

At one point, there were dozens of mining companies staking claims in the Ring of Fire. Now, there are just a handful of junior firms — small companies that are usually looking for new deposits, and haven’t actually started mining yet.

Noront Resources, which says it holds 85 per cent of mining rights in the Ring of Fire, has made the most headlines lately. For about a year, it was the subject of a high-profile bidding war between two Australian mining heavyweights, Wyloo Metals and BHP. Wyloo — which is backed by Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest, who has a history of contentious relationships with Indigenous communities in his home country — won out: Noront shareholders approved the $616.8-million sale in March.

Before that, KWG made headlines in 2016 for promoting the Ring of Fire in a video starring two bikini-clad women. The video, part of a series of KWG videos called “Mining Minute,” stars host Theresa Longo and another woman, identified only as Ashley, sharing five facts about the Ring of Fire. “First Nations is [sic] interested in sharing in the resources of Ontario’s Ring of Fire,” Ashley says, sitting on a swing.

The video has since been deleted. At the time, CEO Frank Smeenk defended it: “Attractive women attract eyes,” he said.

A third company, Juno, holds permits to do exploration drilling at two sites in the Ring of Fire. Earlier this year, an Ontario court found that the provincial government didn’t properly consult Attawapiskat First Nation in granting the permits to Juno, but still allowed the company to go forward.

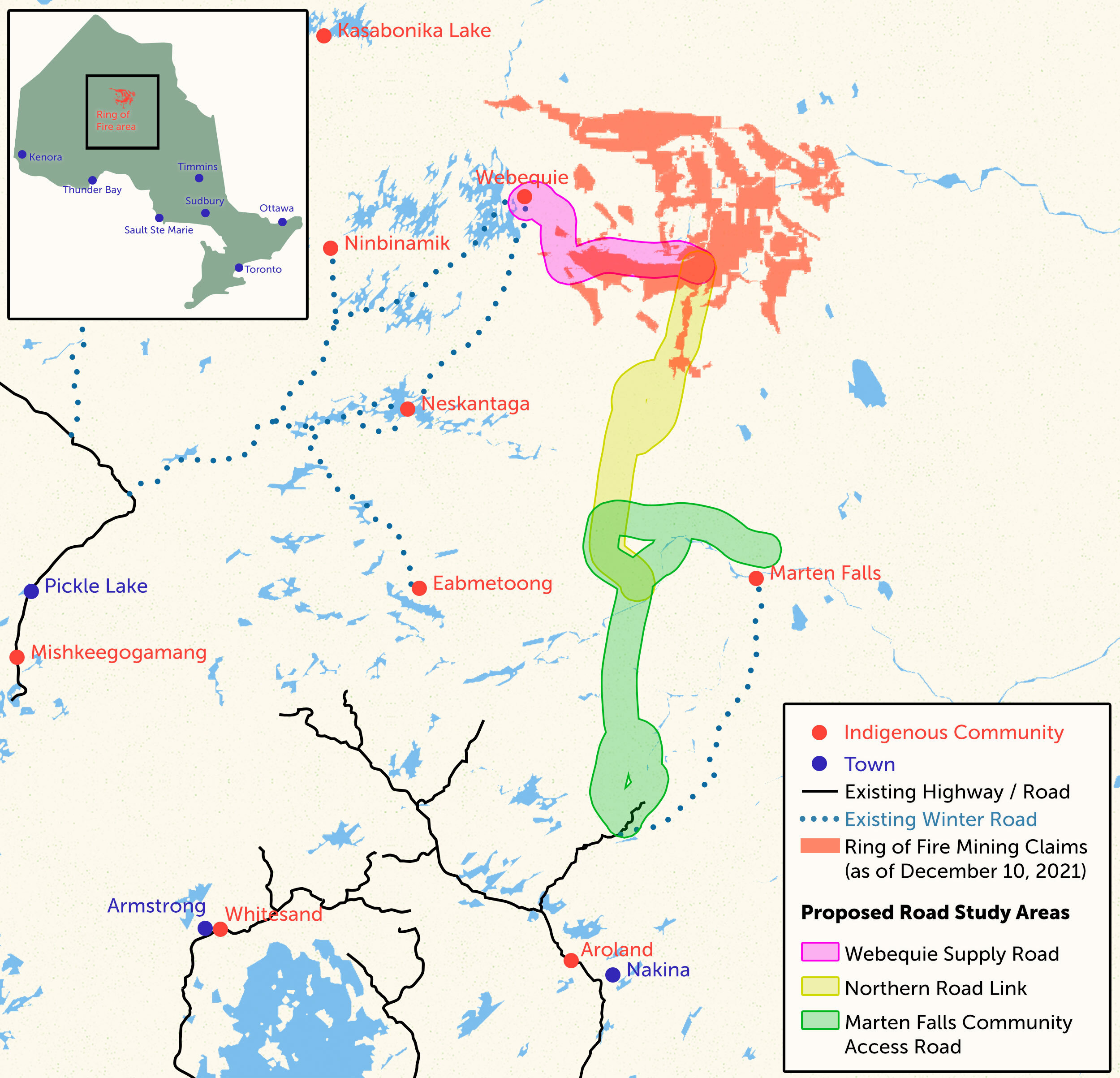

The Ford government is pursuing three road proposals.

The Marten Falls Community Access Road would create a permanent route from Marten Falls First Nation, which is leading the planning process, to the provincial highway network to the south. The Webequie Supply Road, led by Webequie First Nation, would run from the community’s airport to proposed mining developments in the Ring of Fire. The Northern Road Link would connect the two and is being led by both Webequie and Marten Falls First Nations.

Right now, these projects are making their way through the environmental assessment process — or processes. The Marten Falls Community Access Road and Webequie Supply Road are both subject to federal and provincial reviews. Ontario watered down its environmental assessment process in 2020, and the federal rules are generally viewed as more stringent, but some of their requirements overlap.

The Northern Link Road is slightly further behind: Webequie and Marten Falls submitted the “terms of reference” for a provincial assessment, outlining the scope and structure that will guide how the review happens, in April 2022. Ontario Environment Minister David Piccini must sign off on the terms of reference before the provincial review can formally begin. The Northern Link isn’t currently undergoing a federal review, but it may need one later.

On top of all that, the federal government also decided in 2020 to conduct a regional assessment in the Ring of Fire. It’s a new process, so no one really knows how long it might take or what’s going to happen. But the idea is that it will zoom out and look at the cumulative effect of future development, like mines and the infrastructure, on the people and environment in the Ring of Fire. A regional assessment doesn’t deliver a decision on future projects — it is meant to yield information that can be used to guide those decisions in the future, using both western science and Indigenous knowledge.

As those assessments crawl forward, the Ontario government is also still trying to sort out the thorny issue of how to pay for roads and other infrastructure in the Ring of Fire. Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives have carried over a $1 billion commitment previously made by the former Liberal government. But it doesn’t currently have a way to cover the other $1 billion it needs.

For years, the Ford government has been asking the federal government to chip in. But internal federal government documents show that discussions on that have stalled since 2019, The Narwhal reported in May.

It’s hard to tell how the federal government is feeling on that front. On the one hand, Ottawa is tightening its focus on securing supplies of “critical minerals,” which are needed for lower-carbon technology — some of which could theoretically be sourced from the Ring of Fire. But it has also previously told Ontario the Ring of Fire “must be advanced in consultation with all affected First Nations,” and that’s a major point of contention.

It’s complicated. The elected chiefs and band councils of various First Nations — more than a dozen are near the Ring of Fire — have differing opinions on development in their homelands and what it could mean. Within communities, individuals have their own thoughts about the region’s future.

The Ring of Fire falls within Treaty 9 territory. At the turn of the 20th century, Cree and Anishinaabe people there wanted to negotiate to protect their rights amid rapidly growing development in the Far North. Government representatives promised them the rights to hunt, fish and trap on their homelands in a series of meetings, aided by interpreters, in 1905 and 1906. But without the communities’ knowledge, written in a language they didn’t speak, the government representatives added a line to the document “excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.” Canadian courts have ruled that oral promises made as part of treaties are binding. But in practice, settler governments have not kept up their end of the agreement.

Many First Nations in Ontario’s Far North are coping with overlapping crises due to to the ongoing impacts of colonization: long-term boil water advisories, youth suicides, poverty and high food prices, alongside COVID-19. Some, like Marten Falls, are backing road proposals because they see them as a way to improve their communities’ quality of life. Roads can connect them to the south, to economic opportunities and to better services.

“There’s a lack of growth in the community and a lack of infrastructure,” Marten Falls Chief Bruce Achneepineskum previously told The Narwhal. “These are systemic issues that we’re talking about. Why can’t youth be supported in these kinds of essential things that our forefathers had envisioned when they signed the treaty?”

Other First Nations have grave concerns about how the various assessment processes in the Ring of Fire are playing out, given the irreversible impact it could have on their way of life.

In January, Neskantaga, Eabametoong, Fort Albany, Kashechewan and Attawapiskat First Nations sent a letter to federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault, saying the draft terms of reference for the regional assessment are too narrow and puts Indigenous people in “token roles.” They asked Guilbeault to start over with new terms of reference.

“Western ways have led us to a climate crisis, and too many Western ‘solutions’ to this crisis are being built on the further sacrifice of Indigenous Peoples’ territories, rights, and futures,” the letter read. “We will not sit on the sidelines and watch this happen in the Breathing Lands.”

The letter built on a moratorium on development issued by Attawapiskat, Fort Albany and Neskantaga in 2021 — at the time, the three nations said no projects should go ahead until they receive proper environmental scrutiny and First Nations are truly equal partners.

Ford is making it clear that he intends to keep pushing the Ring of Fire forward. In June, he handed the task to a new minister of mines: Timmins MPP George Pirie, a former mining executive, who the government said has a specific mandate to develop the Ring of Fire. (Before that, the role was held by Greg Rickford, who briefly sat on the board of Noront Resources. Rickford remains in cabinet as the minister of northern development and Indigenous affairs.)

For now, it’s not clear if or when a road to the Ring of Fire might happen. Environmental assessments can take several years even under the best of circumstances. And even if that happens, there’s no guarantee that mines in the region would ever be feasible or get approved. But the federal government’s interest in critical minerals — and Wyloo’s purchase of Noront — mean the idea has more momentum right now than it has in years.

First Nations, meanwhile, are continuing to push for their sovereignty and rights to be respected. Neskantaga filed a lawsuit against the Ontario government over the Ring of Fire in November 2021, saying the consultation process has been “inadequate.”

In June, chiefs of Matawa and Mushkegowuk councils opened discussions about jointly running studies and forming some form of Indigenous-led governing body to oversee the regional assessment process, though no final decisions have been made.

“A re-focus on how impact and environmental assessments are done in Northern Ontario is needed,” said Constance Lake First Nation Chief Ramona Sutherland in a statement from the Matawa chiefs.

“A decade has passed since we began talking about the Ring of Fire, and from our perspective, we are nowhere near resolution on the matter. Canada’s reconciling of their relationship with Indigenous People must include the stopping of its continued infringement of Inherent, Aboriginal, and Treaty Rights.”

Updated Aug. 3, 2022, at 12:05 p.m. ET: This article was updated to correct the amount of carbon stored by peatlands in Ontario’s Far North. It is 35 billion tonnes, not 35 million tonnes.

Updated Aug. 9, 2022, at 9:26 a.m. ET: This article was updated to reflect in Metric measurements, rather than Imperial, the number of cars whose annual emissions are equal to 35 billion metric tonnes of stored carbon.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...