Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

I’d just begun my phone call with Oliver Brandes, when the polar vortex blew into Vancouver on January 12. A frigid windstorm shook my townhouse and rattled the windows; just beyond the glass, crows and seagulls scattered, joined in the air by alleyway debris. The scene stood in stark contrast — or so it seemed — to the subject of my call: heat, drought and the end of winter as we know it.

“We’re off the charts in many ways,” said Brandes, who leads the University of Victoria’s POLIS Water Sustainability Project and advises the B.C. government on water issues. After an abnormally warm and dry early winter (the local denouement to the hottest year in global history) B.C. had just released its “Snow survey and water supply bulletin,” which showed the province entering 2024 with barely half its usual snowpack. That’s a provincial average; in many places the situation was far worse, with 15 snow stations recording all-time lows as of January 1, most of them in the interior.

Despite fall rains and a wet second half of January bringing some relief to the coast, the bulletin made clear that B.C.’s drought is now pushing into winter. Much of the province just experienced a brown Christmas; aquifers that would normally be recharging remain depleted across the province; major rivers, including the Columbia, the Peace and the Fraser are flowing at historic lows. “We’re in trouble in January,” Brandes exclaimed. It’s a disastrous portent for what summer could bring to a province that depends on snowmelt for everything from agriculture to electricity and drinking water, not to mention fighting wildfire.

Brandes has been talking about this kind of scenario since long before water scarcity was a public concern in Canada’s wettest province. He advised the province on its drafting of the Water Sustainability Act, passed in 2016, which gives the province wide-ranging powers to limit water use during times of scarcity. Drought has struck repeatedly since then, though not until the summer of 2023 did it affect the whole province at once.

When we last spoke in August, Brandes expressed some frustration provincial authorities weren’t using those powers more aggressively; they waited until July to warn British Columbians a province-wide drought had settled in, and even then Bowinn Ma, minister for emergency preparedness and climate change, limited herself to requesting citizens take voluntary measures like shorter showers. The first real order didn’t come until Aug. 16, when forage-crop farmers were told to stop drawing water from the north Okanagan’s Salmon River to protect spawning chinook. By then, that basin had been in Stage 4 drought for over a month.

Brandes said he’s seen some signs of improvement in the province’s approach to the crisis since then. Above all, he cited the consolidation of authority for water management under Nathan Cullen’s Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. That transfer was announced in October. Previously, water management had also fallen under the Forestry and Emergency Preparedness ministries causing much confusion and delay. Brandes sees the reorganization as a sign Premier Eby and his cabinet are waking up to the urgency — “the gears are creaking into place” — but the true test won’t come until spring.

“There are no more excuses,” he said. “We’ve had our trial run, it didn’t go particularly well but we learned some valuable lessons. The B.C. government has reorganized itself for potential success. Now it’s time to execute.”

But even Brandes was caught off guard by the severity of this winter’s drought, and what it says about the speed at which B.C.’s climate is changing.

“I didn’t anticipate doing this level of really catastrophic response stuff this soon,” he said. “I thought I’d be doing this at the end of my career.”

The wind had subsided by the time our conversation ended. But the temperature kept dropping and now clouds converged above the city. When I started my next call, the first snowflakes of 2024 had begun to fall on Vancouver.

This time I was talking to John Pomeroy, the Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change, from the University of Saskatchewan. He didn’t sound impressed when I told him it was snowing on the coast — it would take more than a single weather system to impact the bigger picture.

What was that bigger picture?

“We’re starting to see the desiccation of Western Canada,” he told me. A perfect example came from McBride, the village of nearly 700 residents in eastern B.C., which recently made headlines for its ongoing state of emergency. After a wildfire forced residents to evacuate last May, the river that once fed its reservoir ran dry, forcing residents to ration water while they weigh options for a new water supply. As Pomeroy explained, a few dry months wouldn’t have brought the village to its knees this way in the recent past. “Their stream used to have glaciers feed into it, which helped them through droughts. But the glaciers have receded out of that watershed and don’t contribute to it now.” This has left McBride utterly vulnerable to droughts it could once have withstood.

Glaciers, and the vital drought-proofing service they provide, are disappearing all across the Rockies. “We’ll have lost most of them by the end of the century,” Pomeroy said.

In the nearer term, the mountains’ winter snowpack — not to be confused with glaciers — is increasingly unreliable. Lower elevation regions in particular are getting more rain and less snow and the snow they do get tends to melt sooner. With the past two record-warm winters, “we’re actually seeing some of the worst-case scenarios for the end of the century under climate change, and we’re seeing them right now,” Pomeroy said. On top of that, precipitation patterns are becoming more volatile, veering between protracted drought and short bursts of intense rain, as happened with the atmospheric rivers of 2021.

These shifts are already wreaking havoc on critical infrastructure throughout Western Canada. Drought forced BC Hydro to import a record amount of energy in 2023. Farmers from B.C. to Saskatchewan, having just endured a catastrophically dry summer of 2023, are bracing for an even worse year ahead. In Alberta, the South Saskatchewan River and other basins are also running so low that the Alberta Energy Regulator warned oilsands operators they may have to curtail production in the coming months. Farther north, the Mackenzie River — a vital conduit to the Western Arctic fed by the Peace and Athabasca rivers — ran so low in 2023 that barges could no longer bring food and fuel to northern communities, forcing them to fly in crucial supplies at far greater expense. These are just a few examples from a litany of consequences stretching into every walk of life.

“Our systems were built for a snowmelt runoff system that had a lot of reliability and didn’t change much from year to year,” Pomeroy said. The end of that reliability “is going to challenge everything we do.”

Two hours later I was driving my daughter home from school in a blizzard, with heavy wet flakes landing on warm concrete in rapidly freezing conditions. Vancouver is famous for what these conditions do to traffic; as I gripped the wheel with both hands, praying to get home in one piece, my concerns about the end of winter began to feel misplaced.

We made it. Then I checked in on my parents. They live in Edmonton, where temperatures were approaching 40 below; the weather station at Edmonton’s international airport hit 45.9 degrees below zero, one of 38 cold-weather records broken across the province that day. My 91-year-old dad had barricaded himself inside his house for the week. He was warm, he had food, he was OK. But my mom, who’s 83, revealed that her furnace had conked out the day before. She was wearing a parka and lying in bed under multiple blankets, waiting for a repairman to show up. No big deal, she said. She stuck it out for 48 frigid hours until Saturday, when workers arrived and installed a new furnace.

All that weekend, Alberta’s power grid balanced on a knife edge, coming closer than it ever has to overloading. This would have triggered rolling blackouts and sent untold thousands of homes into my mother’s situation. Despite BC Hydro’s woes, and the fact that our province also used a record amount of energy that weekend, we were able to send just enough energy across the border to help stave off disaster in Alberta.

By Monday, the polar vortex had crossed the American border, burying states from Oregon to New York to Kansas in snow and freezing temperatures. But in the Arctic, where all this cold air came from, it was balmy, hovering just above zero. The hemisphere had flipped. How could this be? At first I thought this was one more manifestation of climate change; all over social media, people were explaining — incorrectly — that global warming has weakened the jet stream that normally keeps the coldest air within the Arctic Circle; a weakened jet stream allows cold air to spill south, while our warmer air rushes north to fill the vacuum. I spread this message myself.

But then I learned there’s almost no evidence supporting this. Climate change is indeed warming up the Arctic — for Iqaluit to hit 3 C in January, as it did that Monday, is in fact abnormal — but there’s no demonstrable link between that northern warmth and southern cold snaps. Polar vortexes have always been with us, are not increasing in number or severity, and remain perfectly normal. This week of seemingly crazy weather was just winter being winter.

That in itself felt surprising, and even — now that my mom had a working furnace — hopeful.

Still, it didn’t change the bigger picture that Pomeroy and Brandes had described to me. “Yes, we might still get out of this drought, but we still need to be thinking about it in this more systematic way,” Brandes told me. “We have to shift our whole mindset to say that drought is here with us. Water scarcity and water limits are going to be part of what we’re dealing with.” Looking forward to the summer ahead, he noted, “we have a clear indication in January that we’re going to have a very problematic season and year ahead. What are we going to do differently than last year?”

When I asked Brandes what, specifically, B.C. could do differently, he rapid-fired off a list of queries: “Is groundwater licensing completed? Is there a provincial drought plan that makes meaningful triggers to the legal tools that are available to us? Do we have critical flow thresholds set in high risk areas? Do we have regional drought plans so we know, when there’s limited water, how we’re going to share it so we don’t get angry with our neighbours? These are some of the fundamental actions I and many on the ground want to see.”

Nobody’s seen them yet. When I asked B.C.’s Ministry of Water, Lands and Resource Stewardship how they were preparing for drought in 2024, their response was standard boilerplate, low on specifics, high on enthusiasm, seemingly designed to confirm (as more than one person has recently observed to me in private) that B.C.’s drought response plan is actually a communications plan. “We are doing the work now to better prepare for this year,” their email promised, naming three initiatives: “Updating our Drought Response Plan,” “making sure we’re communicating with water licensees ahead of the drought season,” and “strengthening communication to the agricultural sector.”

“If a community would like to discuss drought planning or requires assistance, they can reach out to their local Emergency Management and Climate Readiness regional office,” they added.

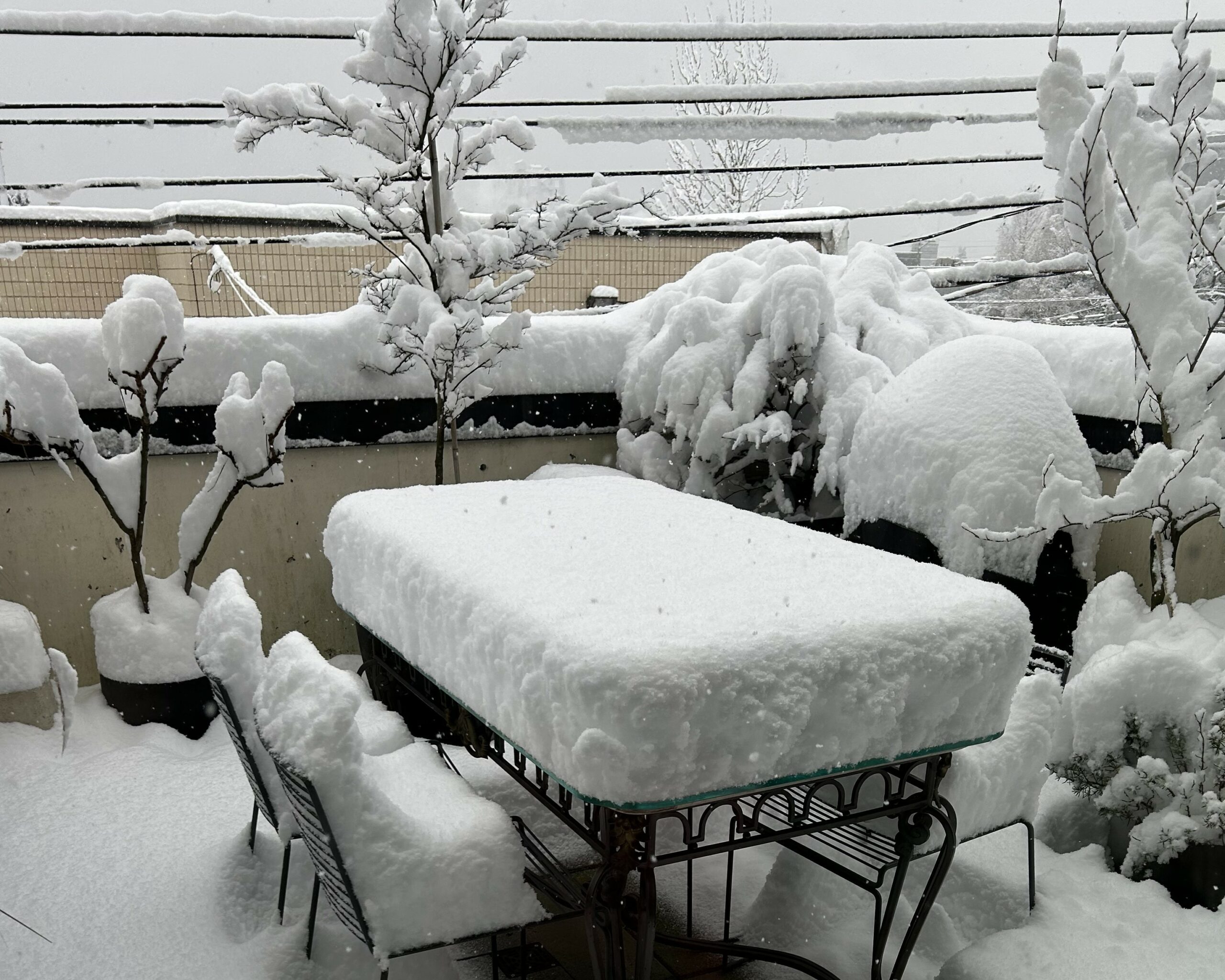

Outside my window, Vancouver’s skies had cleared. But the next day, blizzards buried most of southern B.C., and we got a record 27 centimetres of snow. This time the whole city shut down. My daughter experienced her first snow day, as schools closed across the region.

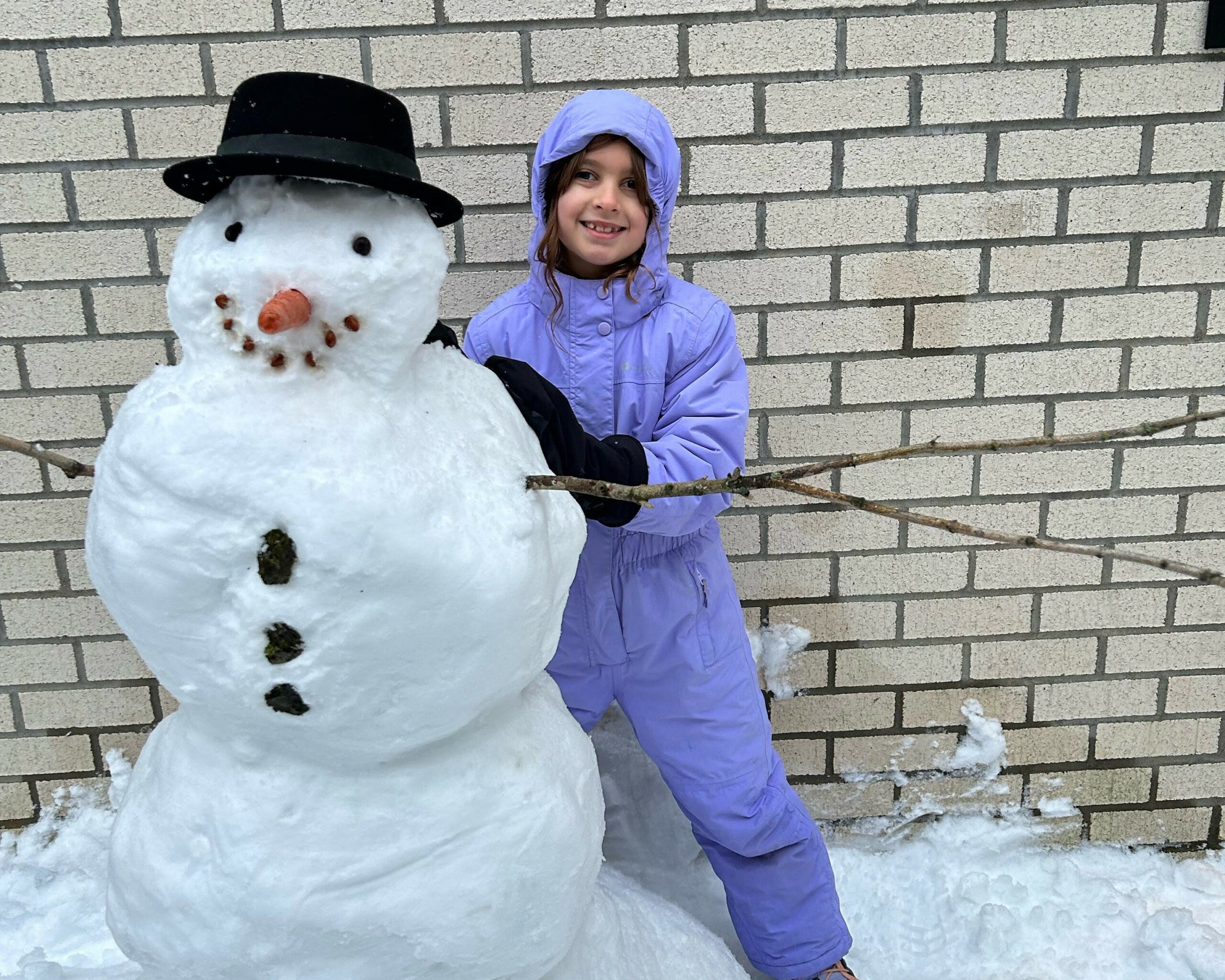

Let’s enjoy it while we can, we agreed, and spent the day outside building snowmen.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion