Court halts tailings increase as First Nation challenges B.C.’s decision to greenlight it

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Peter Kuitenbrouwer is a journalist and Registered Professional Forester who holds a Master of Forest Conservation from the University of Toronto. This article was originally published in The Globe and Mail.

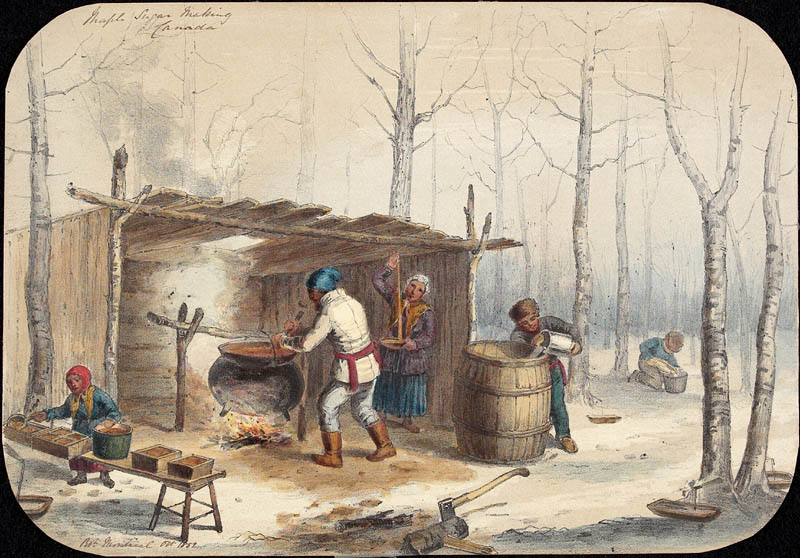

On the farm in west Quebec where we settled in my childhood, the start of spring felt a lot like winter. My mother, from the Netherlands, and stepfather, from California, decided to make maple syrup, a task at which we had no skill. In March, my siblings and I would tuck our jeans into our rubber boots and cross snow drifts taller than us to collect sap from buckets that hung from the sugar maple trees. We hauled the sap in white plastic pails to pour in a drum on the tractor. Icy sap sloshed into our boots, where it mixed with snow. My feet froze. I thought spring would never come.

Our recompense would come after dark in the sugar shack. We hung our socks to dry near the warmth of the wood fire that crackled in the evaporator. Steam enveloped us. Sometimes, before bed, we got a sweet sip of fresh hot golden maple syrup.

And so it was that our experiences as kids would mirror the best conditions for producing sap for maple syrup: deep cold, followed by a warm thaw.

Maples, and other trees, function a bit like pumps; they suck in moisture from the earth as they contract in the cold of the night, and expel moisture when warmth comes during the day. In The Maple Sugar Book, our family’s syrup bible written in 1950, Helen and Scott Nearing of Vermont note: “Maple sap, during the sugar-making season, exerts a pressure from a negative or suction pressure of two pounds per square inch to a positive or expulsive pressure of twenty pounds per square inch.” If a warm day follows a cold night and you make a hole in a maple, the sap will flow.

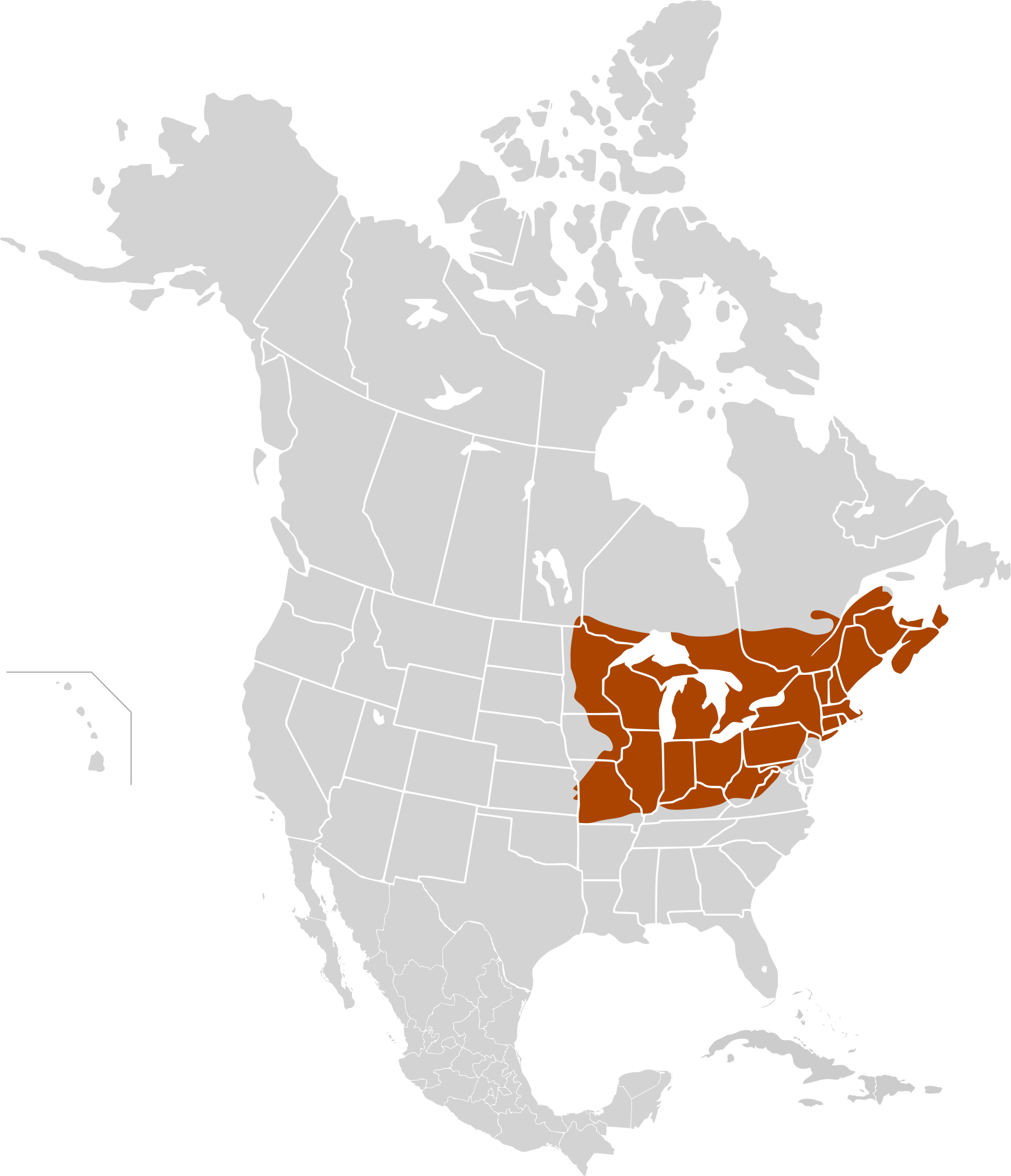

And that sap has flowed so prodigiously here that maple syrup has become intrinsic to Canada’s identity — even before Canada was ever created. In his Histoire de la Nouvelle France of 1609, Marc Lescarbot wrote, “If [Indigenous peoples] are pressed by thirst, they get juice from trees and distil a sweet and very agreeable liquid.” Settlers copied this technique: bore a hole in a maple tree in the spring, collect sap and boil it for a long time. Forty litres of sap makes one litre of syrup. The maple leaf, the symbol of Canada that appears on our very flag, is vital in the process too: Leaves take water from the soil and carbon dioxide from the air, and through photosynthesis, powered by sunlight, make the glucose that trees need to grow. Once the leaves fall, the sugar in the tree works like anti-freeze to keep the tree from freezing.

But with the earth warming, that age-old cycle may stop being so reliable. And that threat could be coming sooner rather than later.

For proof, just look to Quebec, which supplies more than two-thirds of the world’s maple syrup. These are actually banner times: Between 2003 and 2020, Quebec’s annual syrup output has more than doubled, and Quebec producers last year earned more than a half-billion dollars. (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Ontario contribute too, but they are bit players in the market.)

Quebec’s producers are linked through the Producteurs et Productrices Acéricoles du Québec, a cartel that controls syrup supply by limiting the number of taps permitted in the province’s maple trees, and sets the price paid to farmers. The organization stores surplus syrup in the grandly named International Strategic Reserve, in a warehouse the size of five football fields in Saint-Antoine-de-Tilly, near Quebec City, which is stacked with sealed white 205-litre drums of maple syrup and tides us over in lean syrup years. And that’s precisely what the industry just faced: an abrupt thaw last spring dulled the ideal cold-then-warm cycle, and led to a poor syrup harvest. And so, on Dec. 1, the cartel had to release into the marketplace half the reserve — 50 million pounds of maple syrup — to make up the shortfall.

That’s a staggering deficit, though the cartel insists that the release of the maple syrup is a good thing: “It’s not a problem. It’s not negative,” says Helene Normandin, a spokeswoman for Quebec’s syrup producers. “Thanks to the reserve, no one will be short of maple syrup.” Still, it’s enough to make Canadians wonder: What if global warming wipes out the freeze/thaw cycle that’s so critical to syrup success in the long-term? If climate change eventually makes Canada’s winters melt away, and we lose those centuries-old processes of maple syrup production, what remains of Canadian identity?

Christian Messier, a professor of forestry at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, comes by his expertise honestly. He has a small sugar bush himself near Lac des Plages, just north of where I grew up. Working with his wife and son, using buckets and a wood-fired evaporator as we did as kids, Messier makes 100 to 200 litres of syrup every year, depending on the season.

He fears what global warming, and other human-caused change, will do to the providential sugar bush. Drought harms maples more than oaks or pines, he says, which are better adapted to dry periods. The weakened maples, he says, will become more vulnerable to insects or disease.

Invading beetles, for example, hitched a ride on shipping pallets from China and attacked forests in upstate New York; those beetles could decimate our sugar bushes, he warns. He suggests we step up inspections of imported pallets, as Australia and New Zealand have done.

He also believes we should strengthen our maple forests. Maple syrup makers often cut all but the sugar maple trees from their property, since they’re the ones that yield revenue. But mixed forests with many tree species are more resilient, Messier’s research shows. As an example, tent caterpillars prefer to eat poplar rather than maple leaves; encourage poplar trees, and the caterpillars will leave maples to grow.

“Instead of looking at our sugar bushes as a milk cow,” he told me, “we now need to reinvest.” And yet, when he recently told producers at a conference that it is “criminal to have pure maple sugar bushes,” he said, “they weren’t happy to hear that.”

“People say, ‘Let nature be.’ But we have already changed our natural environment. We need to start adapting our forests.”

Christian Messier, professor of forestry at Université du Québec en Outaouais

He also suggests Canadian producers gather maple tree seeds from New York to plant in Quebec and Ontario. He believes that these trees will have the genes to better withstand warmer weather. “People say, ‘Let nature be,’ ” Messier says. “But we have already changed our natural environment. We need to start adapting our forests.”

But this does not appear to be a time for pausing and reflecting in the industry. Quebec’s producers have authorized seven million more taps in Quebec maples (to a new total of 57 million taps) and Americans are investing, too.

Last Christmas, my wife gifted me The Crown Maple Guide to Maple Syrup. Its author, Robb Turner, is an investment banker who branched out to found Crown Maple, an organic syrup producer in upstate New York. He bought several huge sugar bushes, including one 4,400-acre hilltop in Vermont.

The vacuum system that sucks sap from his trees runs from the drop line through the lateral line, the branch line, the conductor line and the main line; some pipes leading to the sugar house reach 12 centimetres in diameter. The sap then goes through something called “dissolved air flotation,” then germicidal ultraviolet light before it arrives at the reverse-osmosis machine, which removes about 90 per cent of the water from the sap on its way to the evaporator. Which is to say: We are a long way from kids in wet socks.

But simply adding more producers won’t necessarily resolve supply consequences in the long-term. A study in the journal Forest Ecology and Management, involving U.S. and Canadian researchers, noted that by 2100 the syrup season will take place a month earlier than is the case right now. Hotter summers also mean that trees will store fewer carbohydrates, so the sugar content of maple sap will diminish.

“Total syrup production is projected to decline over most of sugar maple’s range by the end of the century,” the authors conclude, “except for the far northern range in Ontario and Quebec which project to have moderate to large increases in average syrup produced per tap.”

And it’s not obvious that syrup producers are thinking so far ahead. When I asked Mike Cobb, Crown Maple’s chief executive officer, whether he fears climate change, he replied: “We think about it, but there are limited options as to what we can do about it. We are a young entrepreneurial company, highly short on resources. We don’t have time to talk about that.”

Never have my feet been as cold as in those ice-soaked sock days of childhood. And yet somehow the yearning to make maple syrup tugs so strongly at my heart that all I remember is the romance. In my childhood, when spring eventually arrived in the sugar bush, the fluffy snow became crystals, like sand. As we tromped through deep twisting trails we’d made through the snow to the buckets on the maple trees, we glimpsed, for the first time in many months, the earth, covered in dead leaves. Birds chirped and creeks gurgled. Days grew longer. With leaves yet to open, the forest is sunniest in April.

I’m not religious, but like many people I feel a spiritual connection to the forest. “Tree growth,” the author F. Schuyler Mathews gushed in 1896, “is a constant source of wonder to one who contemplates Nature. The rigid bole, the bracing and far-searching roots, the out-spreading top with its myriad members and its infinite variety of form and expression, all combine to make an organism in which strength, durability, gracefulness and tenderness are all at once the dominant characteristics.” Perhaps it is no coincidence that sugar shacks, built with a cupola in the roof to let out the vapour from boiling sap, resemble chapels.

And so, when my wife and I saw a listing for a farm in Hastings County, about halfway between Ottawa and Toronto, with “five acres of sugar bush,” we bought it. While I work on building us a sugar shack, our syrup-making methods are currently even more primitive than my parents’: We use an outdoor evaporator pan with a wood fire below. And so even as I write here about climate change’s potential consequences on maple-syrup production, I know the oldest techniques are not kind to the environment: burning wood all day and night to make maple syrup is a greenhouse gas nightmare. Reverse osmosis — the process by which most of the sugar is removed before boiling — solves some of this, and Quebec has also vowed to convert oil evaporators to electricity, to reduce their carbon footprint. I try to compensate by planting trees on my farm, but I grant: even the romance isn’t necessarily innocent.

Still, there’s something special about the celebration of the temps des sucres (sugaring off) — a party which is most boisterous in Quebec. After a long, long winter, we rejoice: spring is here! Near my childhood home we would go to La Cabane à Sucre Chez Ti-Mousse, and sit elbow to elbow on long tables with plastic tablecloths. We’d feast on crispy pork rinds, beans with pork, baked omelets, smoked ham, pickled onions and beets, sausages and pancakes, all slathered in maple syrup. But the pandemic has forced cabanes to close to the public for two seasons; Normandin, the spokesperson for Quebec’s syrup producers, said sugar shack celebrations and maple syrup season are so intertwined in the minds of Quebeckers that with pandemic closings, she fielded many panicked calls from people who thought that, if the sugar shack was shut, there would be no maple syrup to buy.

This — the local producer who sells you syrup in bottles or cans, fresh from their forest — is the essence of maple syrup in Canada, and what we cannot lose, and what the cartel cannot store. This is what André Thévet, a monk travelling with Jacques Cartier, described in 1557 as a juice that tasted as delicious as the fine wines of Orleans or Beaune. By contrast, barrels of maple syrup that have sat for years in the International Strategic Reserve exemplify the industrial agriculture model that we increasingly rely on and yet threatens our survival. It’s the same model that brings us produce trekked in from thousands of kilometres away; monocultures that exhaust farmland; pesticides and herbicides that punish flora and fauna and the natural cycle of things. The Producteurs et Productrices Acéricoles du Québec views maple syrup as a commodity, like crude oil or iron ore, and in doing so, it’s as if they are demanding vineyards to pool their varietals to sell bottles labelled “wine.” Quebeckers, at least, are sensible in this regard; most buy their syrup directly from their local sugar shack, fresh, from people that they know.

My whining about the wet socks of my childhood seems a bit infantile when I think of the farmers who taught us to make syrup, on the dirt road where I grew up: Lecot, Labelle, Poulin. They were the original “back to the landers,” as my stepfather Jay reminds me. Totally pure old Quebec: raising families of up to 10 children with no electricity. They made maple syrup because they had no other sugar. When we vote for leaders with plans to fight global warming, that’s the Canada we seek to protect. It is a rugged landscape where we overcome obstacles to thrive; where icy winters give way to the miracle of spring, and bring us the first harvest: maple syrup.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...