Malkolm Boothroyd is a writer, photographer and campaigns coordinator for the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Yukon chapter.

About twenty caribou have blocked the road. I pull over to the shoulder and park. It’s a hot July day on the Top of the World Highway, about 90 kilometres northwest of Dawson City, Yukon. A light haze hangs in the air, smoke from wildfires burning across the border in Alaska.

It’s the Fortymile caribou herd. Some caribou are lying on the gravel, others stand as three-week-old calves nuzzle around their legs. Velvet still coats the antlers of the bulls. Several hundred more caribou are scattered across the mountainsides ahead, and a few dozen are bedded among the stunted alders that furnish the rocky outcrops above the highway.

It’s been slow going all afternoon. I’d only just gotten back on the road after waiting three hours for a hundred caribou to clear the highway a few kilometres back. I open the truck door and step out, trying to make as little noise as possible. I tiptoe around the back of the truck to where my companions, Chase Everitt and Chris Clarke, have parked. Chase is a fish and wildlife technician and a Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin citizen. Chris works with the First Nation’s Land Stewardship Project.

The next moment I’m distracted by the roar of wheels churning through gravel. I look up in time to see a white SUV rounding a corner towards us. The vehicle speeds by without slowing down, quickly closing the gap to the caribou. Chris hammers the horn of her truck, and finally the SUV shudders to a halt and reverses back towards us. “There are laws about not harassing wildlife,” Chase tells the driver, a clean shaven guy with greying hair and Alberta plates. “You need to wait until the caribou move off the road.”

“Are you serious?” the man snaps.

He starts venting about public health measures adopted to control the coronavirus pandemic and then circles back to the caribou. He suggests he should be allowed to do what he wants.

“I’m sick of people telling me what I can’t do in my own country.”

There are stories from a hundred years ago when Fortymile caribou were so numerous that it took days for the herd to cross the Yukon River. The paddlewheelers that plied the river between Whitehorse and Dawson would have to moor up and wait for the caribou to finish crossing. The herd has been through staggering crashes and spikes in the intervening time, from numbering in the hundreds of thousands, to just a few thousand in the 1970s. Concerted efforts to recover the population began in the 1990s. Wildlife authorities in Alaska began an expansive program of predator suppression, while Yukon hunters and the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin stopped harvesting the herd. By 2017, the herd had rebounded to more than 80,000 caribou.

There’s something poetic about the Fortymile herd recovering to a point where it can once again stop traffic, but our Albertan friend doesn’t seem amused. He pulls a U-turn and speeds back towards Dawson, waving his middle finger at us as he disappears.

The Fortymile caribou are one of those animals that everything else seems to revolve around. Bears and wolves follow in the wake of the herd, and the footsteps of countless generations of caribou are etched into the mountainsides. Fortymile caribou sustained the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin, and caribou meat helped to feed the tens of thousands of prospectors who flocked north during the Klondike Gold Rush. This excessive hunting by newcomers drove the herd to crisis, and displaced the First Nation’s harvest. The Fortymile caribou may have faded away for a time, but its recovery is bringing new optimism, as well as new fears.

I’d come here hoping to get photos and videos of caribou to use in the advocacy work I do with the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. The Yukon is in the middle of land use planning for the Dawson region, which will determine which parts of the herd’s range will be protected, and how much development can happen in the rest. This is a critical time for the Fortymile caribou. Some biologists worry that food shortages within the herd’s range could trigger another population crash. Meanwhile, new mining developments could encroach upon the herd’s remaining range. The next few years will shape the future of the herd for decades to come.

The memory of the Fortymile caribou still lingers on the landscapes they once inhabited. Ancient caribou trails line mountains in the Dawson Range, even though the herd has not been seen in these lands for more than 60 years. The herd once ranged throughout the central Yukon and Alaska, some winters migrating almost as far south as Whitehorse. One traveller described canoeing down the White River in 1909, where “for forty miles we were running through one continuous mass of caribou. The narrow valley and high bald mountains on either side, swarmed with the animals.” In the 1920s, the herd probably numbered around 250,000, according to Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game.

Profligate hunting of the Fortymile caribou began at the turn of the 20th century and accelerated through the 1930s as new roads opened the highlands to hunters. Historical accounts from game officers in Alaska described people firing into herds — leaving some caribou crippled, and others dead with their meat left to waste. In a single season, 10,000 caribou were killed by hunters in one game district in Alaska. One warden wrote that “most people are content to believe that the animals are in countless numbers that cannot be exhausted.” By the 1930s, the herd was in serious decline. Wolves and wildfires likely worsened the herd’s freefall, and by 1940 fewer than 20,000 remained. The herd had recovered somewhat by 1960, only to plummet again. By 1975, there were only around 5,000 left, according to the Yukon government. The once expansive range of the Fortymile caribou contracted to its very core, in the hills between Dawson City and Fairbanks.

Thanks to decades of recovery work, there are more than 10 times as many caribou in the Fortymile herd as there were in the 1970s. Still, there hasn’t been a corresponding increase in the herd’s range. It’s hard to say why. The networks of mines that extend south from Dawson City might deter caribou from crossing these habitats, but there are other explanations too. Trees and shrubs are flourishing at ever higher elevations as climate change heats up the north. That means the alpine migration corridors, those places above treeline that once unlocked the central Yukon, may now be too overgrown for caribou to use. It’s also possible that the Fortymile herd has lost its collective memory of its old range and the pathways leading there. Migrations have to be learned, and this knowledge could have died out decades and decades ago with the last of the caribou that ventured into central Yukon.

The herd’s failure to reestablish its old range means that caribou are packed tightly within its core range. Some biologists suspect that the herd has surpassed the carrying capacity of the ecosystems it inhabits — essentially that there aren’t enough grasses, sedges and lichens to sustain 80,000 caribou. Insufficient food makes it less likely for cows to give birth, and more difficult for the calves that are born to survive. There are fears another population crash could be looming. This has led wildlife managers in Alaska to push for more hunting to bring the herd’s population down. The Yukon government and the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin First Nation recently agreed on a new management plan, which includes a small hunt for non-First Nations hunters. It’s a new era for the Fortymile caribou.

The hills surrounding Dawson City trend steadily higher as you go west towards Alaska, and slowly the hilltops begin to shrug off the cloak of the boreal forest. These tundra ridges are the heart of the herd’s summer habitat. In the windswept highlands there’s relief from mosquitoes, and lichens and grasses to feed on. Fortymile caribou give birth to their calves across the border in Alaska, then in late June and early July huge congregations of caribou move into the Yukon, following the ridgelines to skirt the tangles of spruce and alder that fill the valleys.

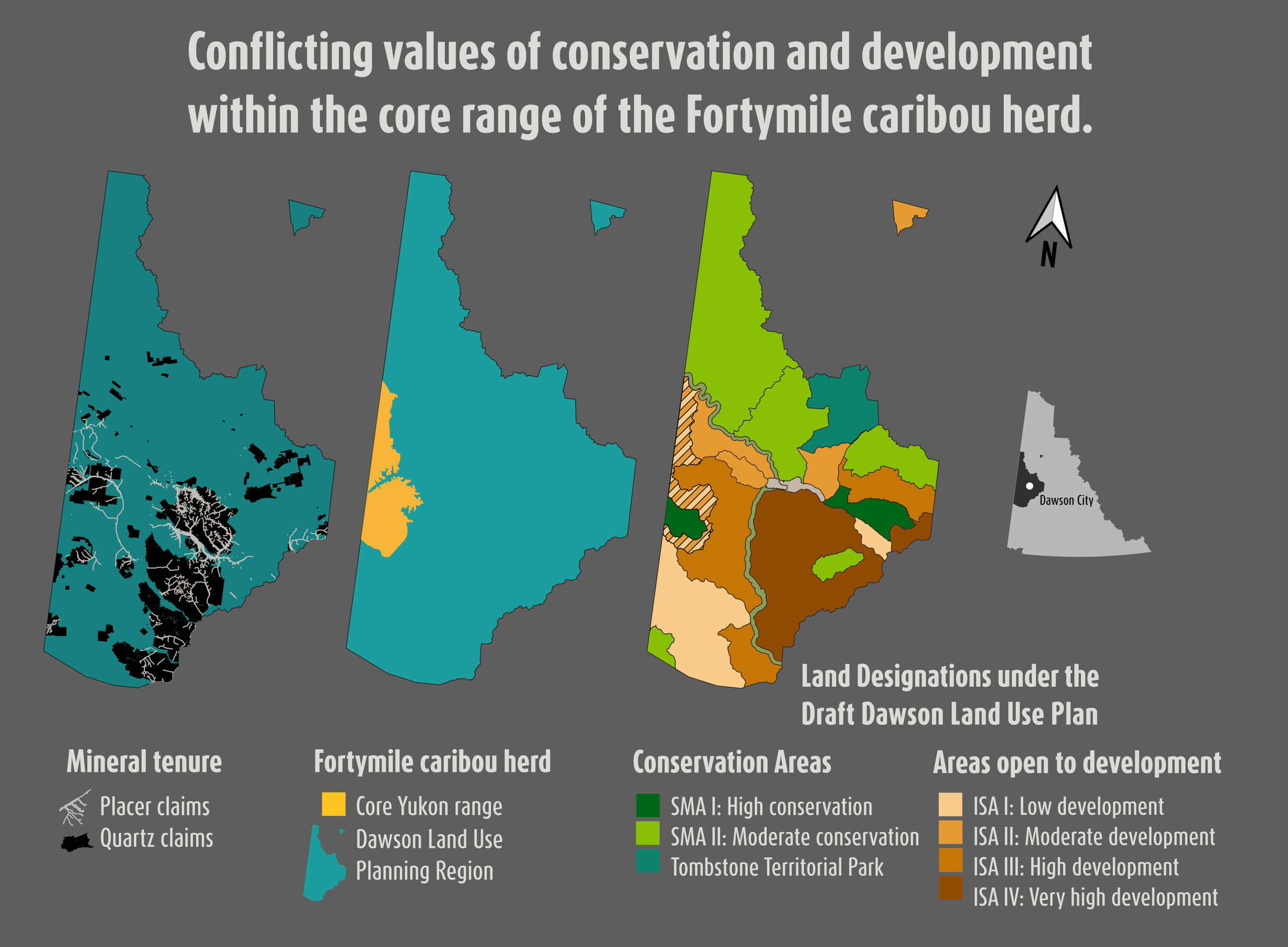

Many of these ridges are also lined with mining roads, winding away towards placer mines in the valleys and hardrock exploration properties in the alpine. Over a quarter of the herd’s core range is blanketed by quartz mining claims. Study after study — from Alaska and the Yukon, to Alberta and the Northwest Territories — warn of the impacts to caribou from industrial development. Developments like roads, mines and oil and gas infrastructure displace caribou from ecosystems, interrupt migrations, and make it easier for predators like wolves to prey on caribou.

Big decisions are looming about which parts of the Fortymile caribou herd’s range will be conserved, and which areas will stay open to mining. In the Yukon, decisions like these are made through the territory’s land use planning process, born from the Umbrella Final Agreement between Yukon First Nations and the Crown. In June the Dawson Land Use Planning Commission released the first draft of its plan. The plan divides the Dawson region into 23 different landscape management units, each with its own land use designation. Forty-five per cent of the region has some form of conservation designation, and the rest is open to varying levels of development.

The plan recommends strong protections for the very core of the herd’s range within the Matson Uplands, a mountain range along the Alaska border, west of Dawson City. But the remainder of the herd’s key range is at risk. Most of the herd’s remaining critical summer range falls within the ‘Fortymile Caribou Corridor’ landscape management unit. This area is divided by elevation, with high elevations open to limited development and low elevations open to moderate development. In alpine habitats, the industrial footprint cannot exceed one quarter of one percent of the landscape. This threshold is relatively low, but it’s calculated by averaging disturbances across the 800 square kilometres of alpine within the unit. High amounts of disturbance could still occur within small areas. Any mining development within ridgetop habitats could interrupt caribou migration corridors, or displace them from key summer habitats.

With a few modifications, the Dawson Land Use Plan could provide strong protections for the Fortymile caribou. It’s critical to keep alpine ridges free from new industrial development, and the plan should designate these habitats as conservation areas. The plan should also ensure there’s ample wintering habitat for Fortymile caribou. Caribou disperse across lower elevations in the winter, and developments within core wintering habitats should remain within levels caribou can tolerate.

The word restore comes up a lot in conversations about the Fortymile caribou herd. There’s restoring the herd to a robust population, and the herd restoring parts of its old range, but it’s equally important to restore people’s connections to the herd.

A few Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin citizens began hunting the herd again in the 2000s, but rebuilding relationships with the herd has been slow. There were generations of Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin who barely hunted the herd. Young people like Chase Everitt are changing that. “I just like seeing animals,” he says. “Even after the shot, it’s not the excitement of ‘I got one’ it’s ‘I get to see it more, see what it actually looks like, everything about it.’ ”

Chase describes his first time hunting the Fortymile caribou. He shot one caribou from a group of four, then the sound of the rifle echoing off the hills set the landscape into motion. Thousands of caribou stirred across the mountains ahead of him. The image sounds a lot like accounts I’d read from a century ago, when people spoke of mountainsides so thick with caribou that the landscape itself seemed alive.

Chris and Chase head back for Dawson. I drive another kilometre up the road, then pack a bag with camera gear and start bushwhacking. I head for the top of a hill, not far from where I’d seen caribou congregating earlier in the day. After a few minutes I break free from a tangle of alders into the clear. Soon a hundred caribou appear just ahead along the ridge. I duck down among a clump of spruce and wait. The caribou burst into a canter and jostle towards me. The herd passes within 30 metres of me. The air is heavy with the sounds of grunting and clicking tendons. Then they’re gone.