Standing on a tree-lined hill in a grassy corner of Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm, Stephanie (Mikki) Adams recalled how she would cherish every chance to go camping, fishing or hunting when growing up in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut.

“Here in the great outdoors, where we’re connected to the land, we’re connected to the environment, we have the air, we have the wind, we have the land right beneath us, right around us,” she explained on a warm, breezy April day, as her light blue jacket glinted in the sun.

“Being able to be on the grass, and smell the nature around you, to hear the birds around you — that itself is healing, and that itself can do a lot for an individual’s mental health.”

Adams now spends her time in Ottawa as the executive director of the Inuuqatigiit Centre for Inuit Children, Youth and Families.

The centre offers recreational, educational and cultural services, many of which draw upon the natural environment, like encouraging young children to use twigs or moss during play time, or engaging in outdoor activities like pulling sleds or building canvas tents.

The centre is one of 10 Indigenous organizations that make up the Ottawa Aboriginal Coalition, which Adams co-chairs. The organizations offer services like housing, daycare, support for survivors of residential schools and other violence, after-school programs and youth employment training. Together they serve roughly half of the 40,000 Indigenous people they estimate are in the Ottawa area.

Several programs use outdoor greenspace, like this spot, for on-the-land, culture-based activities that involve healing, teaching or knowledge-gathering. These activities are critical for moving forward with reconciliation, Adams said. For Indigenous people, “to work on healing yourself, which is accepting what has occurred, really helps when you’re in an environment that is safe and that has nature around you,” she said.

Just then, her voice was drowned out by the roar of excavating equipment several metres from where she was standing.

It was a visceral reminder that the trees, the birds and the grass, and the peace that comes with them, may not be around for much longer.

Premier Doug Ford and Minto Group developer are backing the new Ottawa Hospital campus

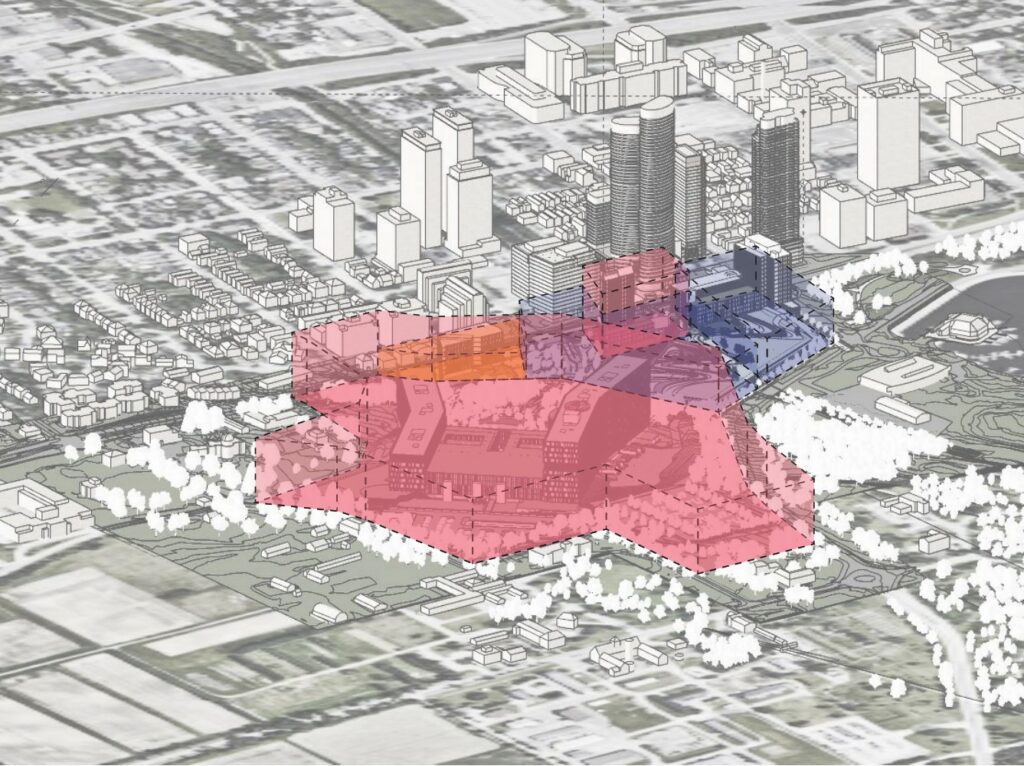

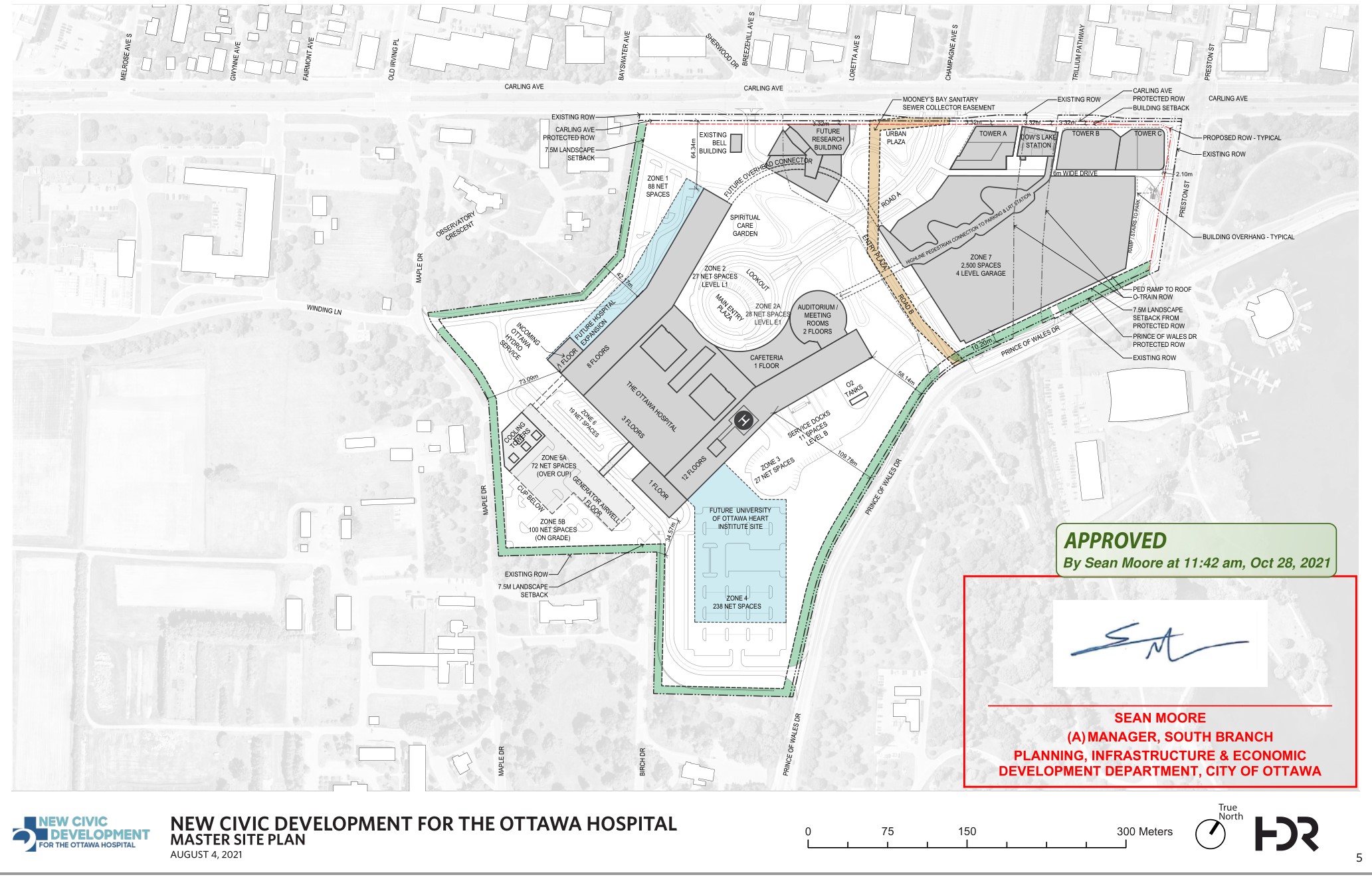

Ottawa is built on unceded Algonquin Anishinaabe territory. The particular parcel Adams was standing on is being developed into a brand new, $2.8 billion hospital, the new Civic campus of the Ottawa Hospital network. The 230,000-square-metre complex on Carling Avenue, southwest of downtown Ottawa, is expected to hold 641 beds, employ more than 5,000 people and serve a wide swath of eastern Ontario, western Quebec and part of Nunavut.

The more than 20-acre site (about twice the size of Parliament Hill) will sit on a portion of the experimental farm, a National Historic Site of Canada. Developing the hospital will mean replacing much of the greenspace in the immediate area with two high-rise towers with an atrium in the middle. One tower would be 11-storeys tall with a helipad and the other would be a seven-storey tower. An adjoining city park is set to be turned into a four-storey, above-ground garage with 2,500 parking spaces.

The current Civic campus, just down the street, first opened in 1924 and was declared 15 years ago to be too old and too difficult to rebuild. The hospital network says the new campus will be “one of the largest and most advanced” in Canada when it opens in 2028, complete with a new trauma centre and a neuroscience research program, and will “help to drive the regional economy.”

The search for a new location has taken years. In 2014, the former federal Conservative government offered land across the street from the current hospital campus. But that location, an agricultural research area, received blowback from residents amid complaints the decision was made without public consultation. That plan was scuttled in 2016. The same year, another potential site owned by the federal government was rejected by the hospital’s board of governors.

Two years later, the federal government signed a 99-year lease with the Ottawa Hospital for the current site near Dow’s Lake, an artificial lake on the Rideau Canal. On Oct. 13, 2021, City Hall approved the master plan for the Dow’s Lake site. The mayor expressed relief that day.

“After 14 years of planning, we’re finally able to help bring this new world-class health care facility to Ottawa that will serve our residents for the next 100 years,” Mayor Jim Watson tweeted.

Powerful figures are backing the development: Watson has been a big booster, while Roger Greenberg, the executive chair of prominent real estate developer Minto Group, is leading a $500 million fundraising campaign. His family, who are company shareholders, donated $25 million to kickstart the effort, earning public praise from the mayor.

The project also has the support of Ontario Premier Doug Ford. His Progressive Conservative government is committing $2.1 billion for the hospital’s construction, through a public-private partnership model. Ford travelled to Ottawa in March to champion a portion of that funding, saying the new hospital has been “desperately needed for decades.”

On Sept. 30, 2021, the Ottawa Hospital held a ceremony to “honour the land” and “respectfully offer thanks” to all Indigenous people. At the event, Ottawa Hospital President Cameron Love said the hospital was “committed to building meaningful partnerships with Indigenous communities, patients and their families.”

Yet some Indigenous communities still feel left out of the conversation.

‘Take your trees, and your freaking parking lot, and shove it where the sun doesn’t shine’

Despite all the high-ranking support, members of the Ottawa Aboriginal Coalition have felt sidelined as details about the hospital’s location and design were signed off on by city officials.

For one, an environmental impact study in 2021 found that 523 trees will be removed from the site to allow for the construction of buildings, something that has horrified some Indigenous organizations which consider the trees to be significant for the health and wellbeing of all people and important symbols of spiritual beliefs and traditions.

“Trees are our teachers and healers, givers and providers,” Adams said.

The city government told The Narwhal it has heard the concerns of residents on the loss of greenspace, and is considering initiatives to incorporate natural elements into the design and to include transit, cyclist and pedestrian access. The parking garage, a city spokesperson said, will have a green roof with two hectares of greenspace, including what they referred to as an “Indigenous garden.”

At the same time, at least one city councillor, Jan Harder, has sharply dismissed concerns around the loss of trees. She suggested that the people in her suburban ward of Barrhaven are not interested in the issue either and that City Hall has more important things to deal with.

People who are “still talking about trees” are in the same group as those who “make excuses” not to support any large city projects, Harder argued during a May 11 Ottawa city council meeting, where councillors approved a framework for dealing with a funding request from the hospital.

“I represent over 70,000 people; I have had not one person call my office, I have received not one email, about the parking garage,” she said.

“So take your trees, and your freaking parking lot, and shove it where the sun doesn’t shine.”

In February, coalition members became alarmed after the city’s planning committee gathered to endorse the hospital’s plan for the parking garage — in the middle of a far-right occupation of Ottawa that shut down major streets, and subjected locals and retail workers to incessant harassment and intimidation.

The timing of the decision caught Ottawa Aboriginal Coalition members off guard. Support staff, already exhausted from the stress of the pandemic, had been fully preoccupied dealing with the impact of the occupation on the health of its clientele. Adams said none of the Indigenous service providers in the coalition were asked to provide any input during this period.

Along with fellow coalition co-chair Allison Fisher, executive director of the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, Adams penned a letter to the mayor and city council on Feb. 14, requesting a “moratorium” on the decision and a “full and meaningful engagement” with Ottawa’s urban Indigenous population “at a time where our responsibilities around climate change has never been more clear and immediate.”

The two expressed their concern “around the entire decision-making process around the hospital.”

“It is still unclear why decisions that will have such a significant change to the Ottawa Indigenous community, and the broader community, are not as transparent and well understood as required,” they wrote.

“We did not realize that in the midst of the occupancy, the city committee still needed to proceed with this decision.”

Coalition members were able to meet with representatives of the Ottawa Hospital on March 7, but the city and the hospital pressed ahead with plans. That month, work began to prepare the site for the new parking garage, which will be built first to accommodate workers building the main hospital grounds.

The hospital has now removed approximately 159 trees from the site, a city spokesperson confirmed on May 17. Of those trees, the city and the hospital said 100 were “invasive species” and six more were considered “dead.” At the time of writing, the city said a further seven “notable trees” were expected to be “relocated to another area of the site” that week.

The city and the hospital say they are working together to preserve as many mature trees as possible and minimize the disruption to birds’ nesting and migration. After the parking garage is built in 2024, the city spokesperson said, “more than 850 trees will be planted on this section of the site.”

The coalition, however, is frustrated with what it considers to be insufficient engagement. On March 18 it put out a press release, reiterating its position. “We were not consulted with at all,” Adams said.

“They’re all hoping it will kind of go under the table and just wash away.”

The hospital says the parking garage is necessary because of its large service area: patients who live hours away will need somewhere close to park after a long drive into town.

But the coalition wants to see the land for the parking garage, and for the entire hospital, used instead as a “Reconciliation Space” for Indigenous people in the city, and to remain an open, public area.

Adams said they would consider such a gesture to be a “symbol” of the city’s commitment to the urban Indigenous people who call Ottawa home.

Ottawa Hospital won’t name Indigenous advisory council members, says coalition was ‘invited’

The city and the hospital both say a wide range of Indigenous groups have been consulted. They say the coalition and its members, as well as other organizations, were “invited” to participate in an Indigenous advisory body for the hospital, but did not confirm which, if any, actually joined.

The mayor’s office and the Ottawa Hospital both declined requests for an interview from The Narwhal.

The hospital “engaged directly with community partners,” including “Indigenous communities,” throughout the planning process for the new campus,” Ottawa Hospital spokesperson Rebecca Abelson wrote in a May 4 emailed response to questions.

The hospital had “worked closely” over the past year with the advisory body, called the Indigenous Peoples Advisory Circle, Abelson wrote. She described it as a “group of organizations that represent or serve the needs of First Nations, Inuit, Métis and urban Indigenous communities.”

According to the hospital’s newsletter, the advisory circle’s inaugural meeting was held in May 2021, and chaired by Marion Crowe, who is the vice-chair of the Ottawa Hospital board of governors and a member of the Piapot First Nation. The body is meant to ensure that “cultural awareness, inclusion and safety are integrated in planning and design of the new hospital,” the newsletter indicated.

Few other details about the advisory circle’s makeup or the agendas of its meetings appear to have been published. Crowe did not respond to a request for comment.

The Narwhal asked the hospital which Indigenous organizations or representatives it had engaged directly with during the planning process, and if it could list the members of the advisory circle and provide its meeting agendas.

In a May 6 emailed response, Abelson said several groups were invited to join the advisory circle, including the Government of Nunavut, the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, Kitigan Zibi First Nation, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Métis National Council.

“We look forward to expanding the [advisory] circle as more organizations and attendees are able to join,” she wrote.

A spokesperson for the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne said they have been included in discussions with a different Ottawa Hospital committee, but did not confirm that they were part of the advisory circle.

“We respect the position of the Ottawa Aboriginal Coalition, but we will rely on the Algonquin Nation to take an official consultation position,” wrote the Mohawk Council spokesperson in an email. Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn representatives did not return requests for comment before publication.

While the hospital may have reached out to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national organization for Inuit did not engage with them, a spokesperson for that organization explained, as they are not technically an Ottawa community group.

Charmaine Forgie, a city manager, wrote May 6 that the city had notified two of the same nations that Abelson listed, as well as Algonquins of Ontario and Métis Nation of Ontario, as part of the site plan control application.

She also noted that there are dedicated locations on the city’s website for public engagement and information about the project applicant, and the city also posts information signs at the site.

In addition, the city’s planning services department “will reach out to the Ottawa Aboriginal Coalition to seek input on which files the community may wish to receive notifications,” Forgie wrote.

Abelson said the advisory circle has held four meetings to date, sharing input about the hospital’s “sustainability strategy” as well as “what culturally safe care and respectful care should look like.”

The hospital is “committed to continuing the journey to reconciliation by strengthening its relationships and engagement with the Indigenous communities it serves to ensure that Indigenous patients and families feel welcome and safe at all (hospital) campuses,” Abelson wrote.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people have long faced anti-Indigenous racism and discrimination in health care facilities in Canada.

Groups focused on disability rights, cycling also feel shut out of decisions around new Ottawa Hospital campus

Coalition members are not the only ones feeling ignored. A citizens group called Reimagine Ottawa continues to oppose the site of the new hospital, citing “concerns about developer influence at City Hall.”

Disability rights groups, cycling advocacy groups and resident community associations have all felt shut out of the plan at one point or another, said Joel Harden, the local MPP, in a May 3 interview.

“A very small amount of unaccountable decision-makers lobby our local institutions,” said Harden, an Ontario New Democrat who is running for re-election in the Ottawa Centre riding on June 2.

Harden is opposed to the parking garage. He said the issue of tree removal remained front and centre for Ottawa voters when he canvassed a neighbourhood near the site of the new hospital recently.

“If the NDP is elected to government, or if we’re part of a coalition government with another party, I will not be quiet until the government of which I’m part knows that the residents, and the ancestral titleholders in many cases of the land, do not want an airport-sized parking garage in a climate emergency,” he said.

Ontario Liberal Party candidate Katie Gibbs, who is running to unseat Harden in Ottawa Centre, also raised concerns about the loss of greenspace and the extent of consultations in an interview.

“This is a perfect example of why we need a broader strategy around protecting our greenspace and our urban tree canopy,” she said in early May.

At the same time, Gibbs said Ottawa residents deserve access to modern health care infrastructure now, and she hasn’t seen alternative location proposals that would allow for the same construction timelines.

“This was obviously not a decision that I was a part of, but going forward, if I was elected, I am committed personally to a process of openness and transparency and public consultation, especially Indigenous consultation, on any decisions, especially when it comes to big projects like this.”

The Narwhal reached out to the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario requesting contact information for their Ottawa Centre candidate, Scott Healey, but they did not respond. Healey lists “supporting the redevelopment of the Ottawa Hospital” as one of his promises on his campaign website.

Larga Baffin, which serves Nunavummiut receiving health care in Ottawa, is facing local opposition

For Adams, who is Inuk, it has been upsetting to see the city move forward with paving over a piece of land that Indigenous organizations have said is important to them.

And it’s happening at the same time that another organization serving Nunavummiut receiving health care in Ottawa is facing local opposition.

In May, some residents pushed back on a proposal for a new location in the city’s south end for Larga Baffin, which runs a boarding home for patients from Nunavut travelling to Ottawa for medical care. During a public meeting to discuss the proposal, one resident complained about the impact on the neighbourhood’s water pressure.

“I bought this house here and I spent a lot of money on this house. I can’t move anywhere else,” she said, according to a report in Nunatsiaq News.

“So I’m just saying it’s not fair that the city will amend the zoning without considering the existing residents … we were here first.”

Area councillor Diane Deans, who is running for mayor, also raised her own concerns that the development was oversized.

The irony of local residents rejecting a proposed Indigenous site on unceded territory, while taking away land currently being used for Indigenous healing, was not lost on Adams.

“It would really show a lot of faith on non-Indigenous people to show commitment and acknowledgement of the atrocities that have occurred to Indigenous people in the past, in the present and that is still currently ongoing,” she said.

“It would be excellent to see them act in good faith, to provide this space not only to Indigenous people, but to keep it open to the citizens of Ottawa as a greenspace for healing.”