In mid-July, the majority of the Ottawa Light Rail Transit (LRT) line was shut down for over a week after lightning brought down 900 metres of overhead wires used to power the trains.

A few days later, OC Transpo took several trains out of service after an operator felt the vehicle vibrating. Transit officials ordered an inspection which would reveal a faulty part in the wheels.

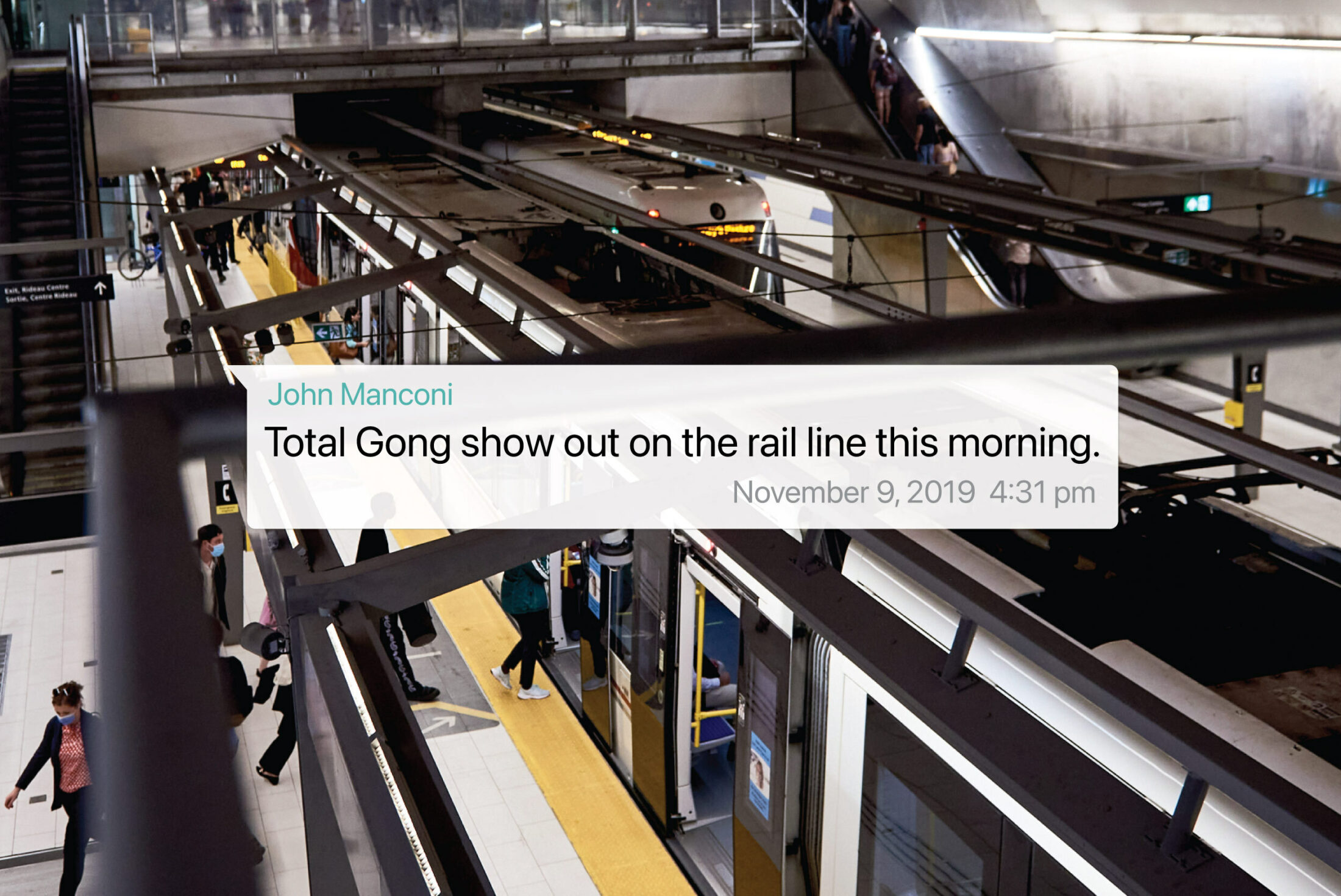

These are the latest incidents in the bewildering, confounding saga of the $2.1 billion, 13-station Ottawa LRT that has struggled to stay on track since before it went into service. From it’s conception, the rail line has seen two huge sinkholes, a tunnel collapse that trapped several workers, multiple lawsuits over construction delays, a series of breakdowns in good and bad weather, deformed wheels, failing computers, stuck doors and two derailments that were six weeks apart and shut down the entire line for nearly two months.

In light of all this, the Ontario government called a public inquiry into the Ottawa LRT in November 2021 to investigate the decisions and actions taken in the lead up to and construction of the line.

The commission collected more than one million documents — identifying more than 10,000 as relevant — and conducted more than 90 witness interviews ahead of public hearings held from June 13 to July 7.

“We serve you,” Justice William Hourigan, the Appeal Court justice leading the inquiry, told the public just before the hearings. “We need to understand what went wrong, who did what, and we’re going to get those answers for you. Absolutely we are.”

Over the course of three weeks, the public heard from Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson, the companies involved in the construction and maintenance of the LRT and transportation authorities overseeing the line. One common thread was political pressure and the role it played in simultaneously constraining and rushing a train service into operation.

The inquiry is a rare and detailed glimpse into the complicated bureaucratic process that saw huge sums of money committed by three levels of government to a project that is theoretically designed to slash emissions and make movement easier. A report is due at the end of August, with a possible deadline extension to the end of November.

Here are 11 things we learned from the evidence and testimony presented at the Ottawa LRT public inquiry.

1. There is a lot of finger-pointing

In its opening statement, French train manufacturer Alstom said both the city and Rideau Transit Group, the consortium of companies building the rail line, knew there were issues with the system before it launched in 2019 — over a year (or 456 days to be precise) after the city was meant to take control of the line. The hearings revealed that date was promoted by Ottawa’s mayor and council to coincide with Canada150 celebrations, but was never met.

“All the parties were aware that the system was not ready” to open to the public, Alstom’s statement said, but the city and Rideau Transit Group “pressed ahead anyway.” It continued that, rather than delaying the opening, the city pushed for the September 2019 open date, “no matter what.”

The City of Ottawa denied this in its opening statement, saying it was “not in a rush to open the system.” It added that “at no time” did any of the construction companies say the system wasn’t ready.

In his testimony before the public inquiry started, Mayor Watson said that while he had concerns about construction delays and technical issues during pre-launch testing, the staff “were satisfied” with the line and believed it to be “substantially complete.” Watson told the inquiry he was “not an expert in running a train system,” and relied on the professional expertise of staff and consultants during the construction and launch of the system.

John Manconi, the former head of Ottawa’s public transit agency OC Transpo who oversaw the launch, told the inquiry the city had a panel of 40 experts managing the whole system that “exceeded what it theoretically and technically and contractually could have and should have done.”

Meanwhile, the Rideau Transit Group said the city didn’t do its part to properly “sensitize” the public for a new rail line and challenges that may come with using it. The group also said it was “let down” by Alstom, which was “late in delivering the vehicles.”

Former Rideau Transit Group CEO Peter Lauch admitted there “probably was” political pressure to launch the LRT in 2019 because of “a huge advertising campaign and a lot of commitments, and it is important, you know, the politician doesn’t want to lose face.”

“That might have led into it, but as I said, I mean, it did not take away from all the peripheral systems, all the support systems. I mean, if we failed the safety issue, if we failed something, we wouldn’t have passed.”

2. Ottawa LRT’s public-private partnership made decision-making difficult

The Ottawa LRT was built through a public-private partnership, or P3, where government agencies and private-sector companies collaborate on a major infrastructure project. The winning company (or companies) build and maintain the project, helping to finance it, and generally hand over ownership to the government after a set period of time and repayment.

In the case of the Ottawa LRT, Rideau Transit Group — a consortium of companies including ACS Infrastructure Canada, EllisDon and SNC Lavalin — took on $300 million in private financing, which the city would pay back in monthly installments over the 30-year contract that began once the system was up and running. If the consortium was late in hitting that target handover date, they wouldn’t get their much-needed funding.

At the public hearings, the commission lawyers suggested this contract arrangement was detrimental to the development process. Rideau Transit Group “was under enormous financial pressure because of the model,” said John Adair, co-lead counsel for the commission.

Rideau Transit Group CEO Nicolas Truchon said financial pressures became more strained as deadline day approached.

“Is it your view that, on the [Rideau Transit Group] side, that better decisions should have been made and would have been made were it not for the desire to achieve the financial component?” Adair asked Truchon.

“Yes,” Truchon replied.

3. The city refused to test the Ottawa LRT with a soft launch

In its opening statement, the Rideau Transit Group said the City of Ottawa’s “misguided decision” to start the LRT without a soft launch, which would have required testing a section of the rail line at full passenger capacity for several days.

Many people told the commission that a soft launch is “best practice” to ensure a rail line is working well and sort out any issues that may occur.

But, Matthew Slade, a member of the Ottawa Light Rail Transit Constructors and Rideau Transit Maintenance, told the commission the idea of a soft launch was “shut down vehemently.”

“I would never contemplate opening a rail system without a soft launch,” Slade said. “There are just too many moving parts and unknowns, and you can test and test, but until the system is actually being used, you don’t know how it is going to react or behave.”

“We should have taken more time to ensure, in retrospect, that the system was severely tested or stressed to flush out any issues. The more time you have to test and stress and communicate with all the parties on how to resolve issues, the better off the system is going to be …”

Mario Guerra, CEO of Rideau Transit Maintenance

Slade said he raised concerns about launching the full system on two separate occasions. He was turned down both times. City officials told him it would cause too much disruption for transit riders who would have to use a combination of buses and the LRT for their commute.

“I would describe it quite simply as political,” Slade said. “The level of attention from the media and the politicians was quite immense, not something I have experienced before.”

4. ‘Cancellation was not an option’ for city officials in the days before the launch

After some prodding, former rail director John Jensen admitted on the first day of public hearings that the decision to move up the launch of the LRT in 2017 — in time for Canada 150 celebrations — was “not coming from the experts.”

“If you could please just confirm that where it was coming from was the mayor and council,” Adair asked.

“That’s correct,” Jensen said.

The city’s director of rail operations, Michael Morgan, denied there was any political pressure ahead of the LRT launch, rather confusion and miscommunication between the various parties bringing it in service.

“We would look at the state of the stations, the state of the fleet and none of it was ready,” Morgan said. “And so it became this kind of conflict where what we saw on the ground wasn’t matching what they were telling us. And so that was probably the biggest challenge for the project was just the lack of understanding of when the project was going to be finished.”

But two days before the 2019 launch, in a WhatsApp group he set up in mid-July 2019 for a number of city officials to monitor progress of the LRT, Manconi wrote “cancellation of launch is not an option.”

“I need everyone to think of Plan B, C, and D,” Manconi said in the message.

“I don’t know what caused him to send this note but he’s always planning for a contingency scenario,” Morgan said. A few days earlier Manconi messaged that issues with radio resets and late trains were “stressing me out.”

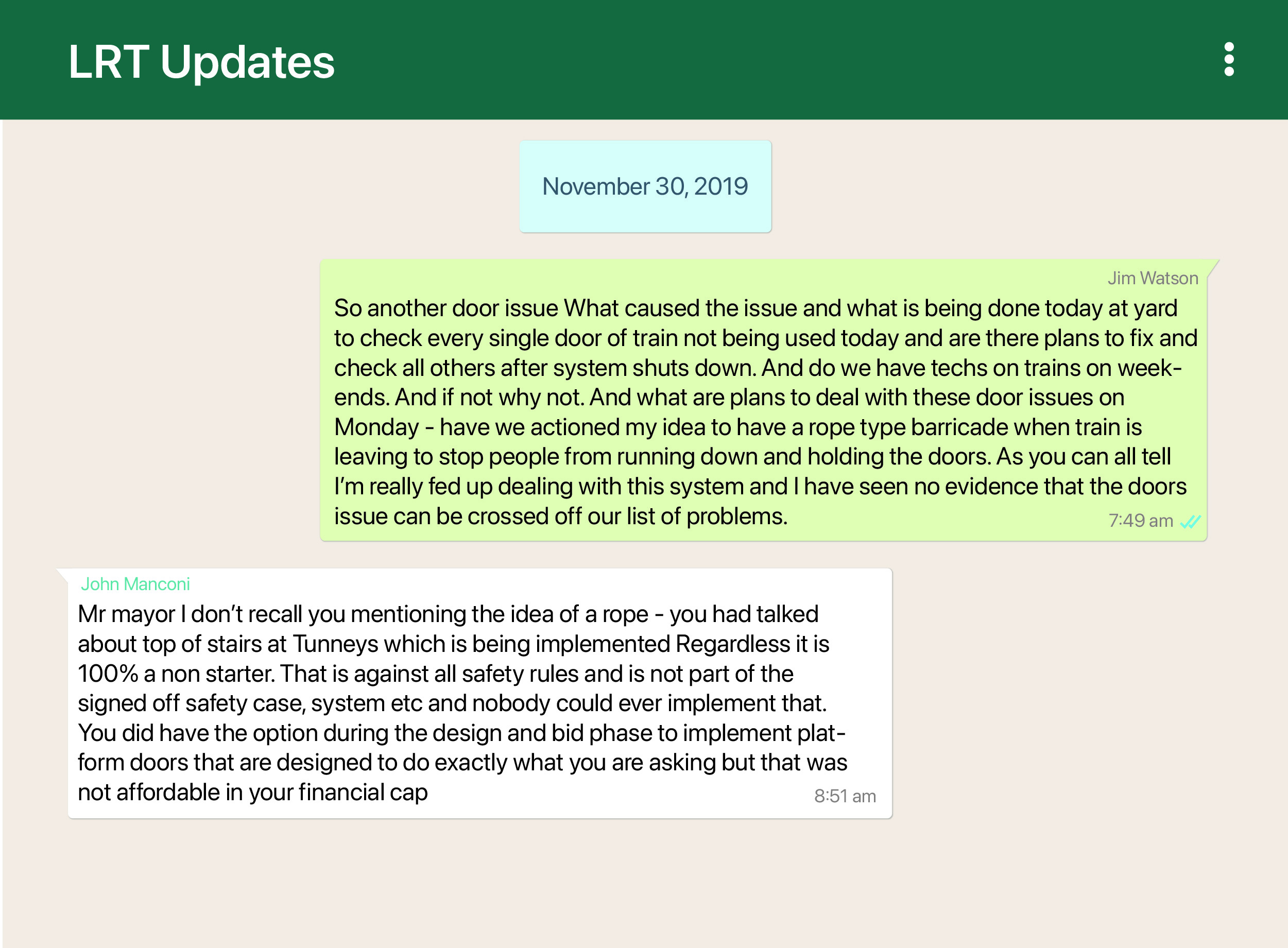

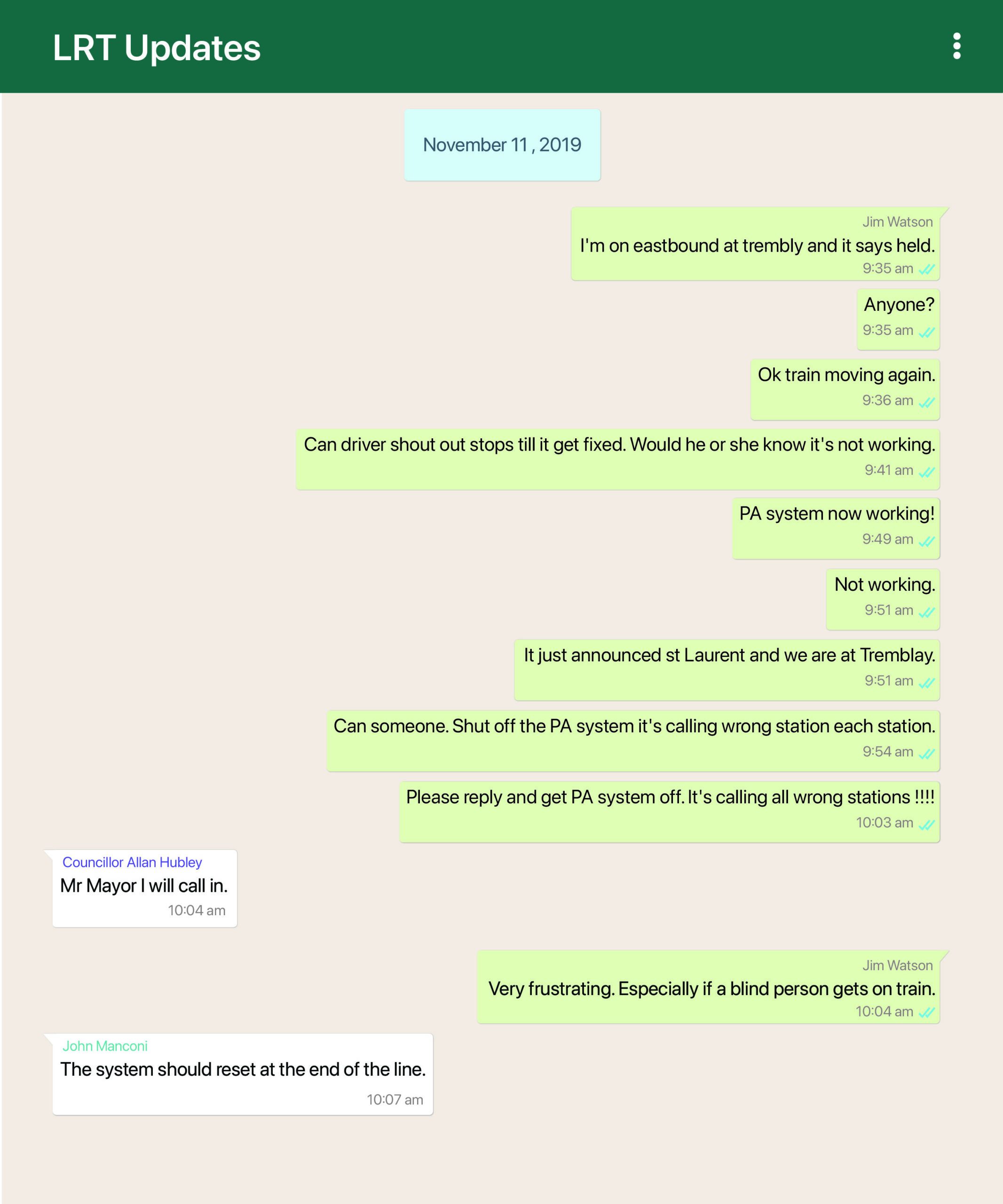

5. Ottawa mayor unleashed barrage of orders around LRT on private WhatsApp group

Manconi’s WhatsApp group was first revealed at the public hearings, and became a key and repeated source of information throughout. It was the main communications channel for several city officials, including transit chair Allan Hubley and members of Mayor Watson’s staff. The mayor himself didn’t join the chat until October 2019.

City officials would use the chat to get daily updates about the trains during the 12-day trial run, as well as information about the LRT’s performance and issues.

The transcript of the chat paints an image of a chaotic time, as public servants and consultants workshopped the day-to-day mishaps. Through various messages, the commission was shown an agitated mayor who, according to Manconi, was “loosing (sic) his mind” and constantly giving orders that seemingly ran contrary to safety and technical standards. Public servants complained about maintenance staff and described them as “idiotic” among other unflattering descriptions, and there were observations of an axe-wielding vandal one day and a spilled box of blueberries another; all of this among an avalanche of technical challenges. For the most part, the chat shows public servants and consultants patting themselves on the back, with emotions tensing largely when politicians or media got involved.

Watson testified that the WhatsApp group was “not a decision-making body” but a “communications tool to try to make our job more efficient, when we’re asked to make decisions — probably several dozen over the course of any couple of hours — on a wide variety of issues.”

“Any issue of substance would not go in a WhatsApp,” the mayor said.

But there are a barrage of messages from the mayor demanding updates about every aspect of the LRT, sending out orders and worrying that “our reputation is in tatters.” He even sent minute-by-minute thoughts while using the LRT and asked for help to shut off the announcement system for “calling all wrong stations !!!!” and requested a red-vest support staff to ask passengers to remove their backpacks so more people could use the train.

In one instance, Watson worried why the OC Transpo Twitter account was presenting different information than what was in the chat. “Why is the twitter account still saying delays?? It’s been 20 minutes yet you tell me it was fixed in five minutes,” he wrote.

In another instance, Watson was concerned about multiple train faults. “This is ridiculous. I want parallel bus service ready to run all next week as a backup. We have zero credibility at this point,” he wrote.

“I am furious I start the morning with a break down and end the afternoon with another one,” he wrote two months into the LRT being operational. A few days later, after a series of door and brake issues that stopped trains from working, he said, “I don’t think things are getting better. We now seek (sic) to have a wider array of problems.”

Watson even sent orders to set up meetings with Rideau Transit Group and Rideau Transit Maintenance officials. “Hold all payments to them and they are not to receive a cent until I personally give you permission,” he wrote.

![WhatsApp messages sent Oct. 22, 2019: John Manconi at 8:51:06 am: We are dealing with multiple trains faults. Service is running single track but in the west end Tunneys to Hurdman extensive delays. We are escalating to [Rideau Transit Group] and [Rideau Transit Maintenance] executives as this is unacceptable. Jim Watson at 8:59:25 am: This is ridiculous. I want parallel bus service ready to run all next week as backup and i there is a problem detected then the busses go out right away. I am sickened to read these messages Jim Watson at 9:00:09 am: I want [Rideau Transit Group] and [Rideau Transit Maintenance] senior officials in my office Monday. Please liaise with serge to set up meetings Jim watson at 9:00:20 am: How many trains have failed and why is cause John manconi at 9:02:27 am: On a conf call right now. John Manconi at 9:19:59 am: We had 3. We cleared out one of them and that has improved things significantly Jim Watson at 9:25:28 am: Hold all payments to them and they are not to receive a cent until I personally give you permission](https://thenarwhal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ottawa-LRT-2-Parkinson-scaled.jpg)

Five days after adding Watson to the group chat, Manconi wrote, “Mr. Mayor I beg you please I am getting so many messages from you on multiple channels and your staff. I will answer every one of them. All being actioned. We are drowning in message overload.”

Manconi used multiple WhatsApp groups to give instructions and analysis. At several instances he calls Alstom and Rideau Transit Maintenance staff “clowns,” “morons” and “idiots.” In another chat with public servants organizing the launch, he asked colleagues to put out tweets with updated information about the train service because the “mayor is upset.”

6. The testing of the Ottawa LRT was rushed; the criteria for approval was lowered

Originally, the idea for testing the Ottawa LRT was to ensure it worked perfectly with a full set of 15 trains for 12 consecutive days. But the trial was plagued with failure after failure, so the criteria was changed to just 12 days of near-perfect operation, no longer consecutive and with just 13 trains.

Former Rideau Transit Group CEO Peter Lauch told the commission that Manconi was the one who proposed to weaken the criteria. Manconi now does consulting work for STV Inc., the firm that advised the city throughout the development of the project. Lauch said the new criteria was proposed to help the consortium pass and start getting paid.

Lauch told the commission, “With respect to our board, everyone agreed with that.”

Other evidence at the commission indicated that Manconi and his team wanted to use their discretion in making pass/fail decisions for some days of testing. The commission was also told the independent certifier team leader wasn’t present for the testing, leaving oversight to a colleague who had graduated only four years prior.

I am furious I start the morning with a break down and end the afternoon with another one.

Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson

The commission also heard from a train system engineer who said the final testing of the Alstom trains was “compressed.” Testing only started a few weeks before the system became operational. Any issues identified were not fixed, including things like trains losing power, the train shutting down if someone stopped the doors from closing and the glass door in the operator’s cab cracking. Addressing such issues could have taken months and were waived by the city.

“Through trial running, we had an unacceptable failure rate and we had trouble getting technical support from the vendor (Alstom),” Lowell Goudge, the train system engineer and train safety certifier, said.

For its part, Alstom was meant to have four kilometres of double tracks along the line to test its trains but was only given a short piece of track in the railyard. It was also behind on its testing schedule due to delays in assembly.

7. The maintenance director was on the Ottawa LRT before it derailed in September 2021 and ‘didn’t think he was going to make it’

On the last day of public hearings, the commission was presented with a video of the derailment last fall. It showed Steven Nadon, the maintenance director of Rideau Transit Maintenance, getting off the train moments before it veered off the tracks.

Guerra, of Rideau Transit Maintenance, told the commission Nadon had “heard a clank sound beneath him and he thought a cable had come loose or that something was dragging and as such he told his wife to get off because he didn’t think he was going to make it.”

Guerra said Nadon had no way to know the train would derail, and that he followed protocol by informing maintenance crews about the sound.

The video shows clouds of dust and gravel from the tracks visibly hitting the train, which Guerra agreed should’ve been visible to anyone watching the train.

An investigation report looking into this derailment identified inattention as a contributing factor, as well as a “human waste smell.” In fact, the LRT operator that day testified that he was communicating with the control room about the smell of human feces on the train before it derailed.

The cause for this derailment was later identified as loose bolts.

8. Alstom had just two weeks to repurpose its trains to carry the volume of a subway train on the Ottawa LRT

The trains used on the Ottawa LRT line are the longest light-rail trains in North America and had never been used before, according to testimony from Yves Declercq, an executive with Alstom. The city gave the company two weeks to upgrade its design to meet Ottawa’s requirements, which included making the train even longer than proposed in order to serve 24,000 passengers an hour. “That is the size of a subway train,” Declercq said.

To do that, Alstom had to increase the number of doors from eight to 14 and use a different engine, one that is similar to the New York City Subway system.

“We were pushing the limit,” Declercq said. “And that does explain, in part, the problems that were incurred later. So we were at the limits of the concept and came across new problems that we don’t usually come across.”

When pressed for examples for these troubles, Declercq said “like derailments” and other technical problems.

Declercq also revealed that Rideau Transit Group came to Alstom after it had already lost its initial bid, and after the consortium’s first choice, Spanish company CAF, was disqualified by the city. This was a “very rare” occurrence, he said, adding that his company made it clear to the city that the trains they wanted didn’t yet exist but could be developed.

The trains were eventually manufactured in Ottawa because the city had a 25 per cent Canadian content rule in place to qualify for federal and provincial funding. But this wasn’t easy: the commission heard that Alstom, which didn’t have a large North American presence before its Ottawa contract, struggled to find skilled workers for the task. It didn’t have an overnight maintenance supervisor at the time of the September 2021 derailment.

As for the derailments, Declercq said the Ottawa LRT tracks are “non-compliant” with its trains.

9. The two companies that made the trains and their computer systems worked in silos

While Alstom made the trains for the Ottawa LRT, Thales Canada Inc. created the computerized signalling system that would control the braking, propulsion, doors, track sensors and other movement-related functions. This was the first time a Thales train communication system was being used in a light-rail vehicle.

Thales project manager Michael Burns told the commission his company and Alstom were working in silos and not collaboratively.

Rupert Holloway, the SNC-Lavalin vice-president who oversaw the building of the train system from May 2018 to May 2019, agreed. He said the construction leads spent a lot of time building the tunnel (“a world-class piece of civil engineering”) but didn’t focus enough on “the integration challenge” — making sure several systems worked in sync in the case of an emergency.

“We certainly failed in regards of tackling that challenge as effectively as we could have done,” Holloway told the commission.

During pre-launch testing, for example, Burns said his company discovered Alstom had put in a safety measure that would force the train to stop if the emergency brake was applied too many times. Thales already had its own safety measure for emergency braking.

When the trains were operational, there was an instance of a woman getting caught in a door that closed early, though no serious injuries occured. Burns said the Thales system would have re-opened the door if something blocked it from closing. An investigation into that instance showed Alstom had a different command in place.

10. The budget for the Ottawa LRT did not take into account true costs of construction, transportation and inflation

Former city treasurer Marian Simulik told the commission the $2.1 billion budget for the first stage of the LRT — a number Watson campaigned heavily on — didn’t account for more than $400 million in inflation and $177 million in construction and transportation costs. These costs would be absorbed by the city, which tried to save money wherever it could to make room for this: the downtown tunnel wasn’t built as deep as planned and the University of Ottawa station was switched from an underground stop to an aboveground one.

When asked if there were ever discussions about the budget being insufficient for the city’s LRT plans, Simulik said, “I don’t remember any discussion of it being insufficient.”

“We basically trusted the private sector to act reasonably and produce a document or a bid that reflected what they thought the cost was going to be,” she said, adding that $2.1 billion was the absolute cap for the city’s expenditure on the LRT.

When asked if there were concerns about whether this cap may have “introduced or increased a risk that the private sector might overpromise in order to get under the cap or meet the budget,” Simulik said, “No.”

Others, however, expressed concern at the hearings that the budget wasn’t sufficient. Rob Pattison, who headed the LRT division for provincial agency Infrastructure Ontario, told the commission “the budget was not up for debate” and worried at the time it was proposed that it may lead to “a failed procurement.”

11. Everyone knew the Ottawa LRT would not provide reliable service

The City of Ottawa willingly accepted an LRT system that it knew was unreliable.

The commission was told the system was never tested in its entirety before it was opened. At no point were 15 double-car trains tried on a normal service schedule before passengers stepped aboard. In fact, the commission was told there wasn’t a single railcar that didn’t have a reported and unaddressed issue when the LRT opened to the public.

“We should have taken more time to ensure, in retrospect, that the system was severely tested or stressed to flush out any issues,” Guerra, of Rideau Transit Maintenance, said. “The more time you have to test and stress and communicate with all the parties on how to resolve issues, the better off the system is going to be” when it’s being used by passengers.

Rideau Transit Group CEO Nicolas Truchon told the commission there was no discussion during the construction phase about how the entire system would work in real life, that everyone was just trying to meet their conditions and get sign-off from a number of independent certifiers.

“At the end of the day, there’s very little discretion,” he said. “I think the question should be whether or not those conditions should have been a little more all-encompassing … There was little room for anybody to raise their hand and say, ‘Well, I’m sorry, I don’t think we’re ready.’ ”

Updated on Aug. 9, 2022, at 10:56 a.m. ET: This story has been updated to correct that the Ottawa LRT launched more than a year after it was meant to start up under the city’s control, not two years.

Updated on Aug. 10, 2022, at 5:03 p.m. ET: This story has been updated to correct a photo caption that suggested the train pictured was built by Alstom, when in fact it was built by a different manufacturer for the second phase of the Ottawa LRT.