Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

At first, Andrea’s experience with Pacific Wild Alliance was “amazing,” she says. She got to see beautiful places while working as a deckhand on photography and film shoots on B.C.’s central coast.

Andrea, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, worked with the B.C.-based environmental non-profit for the first time in 2014. She worked with the organization’s co-founder, Ian McAllister — one of the province’s most prominent wildlife photographers — and felt lucky to experience the Great Bear Rainforest, a region where eagles fly above old-growth forest, wolves roam the beach and humpback whales breach in ocean inlets.

But the serene natural environment didn’t mirror the work environment onboard Ian’s catamaran, Habitat, she says. There, she says, she witnessed verbal harassment and what she describes as “dangerous” boating practices by Ian, now in his 50s, who was executive director of Pacific Wild at the time. She also says he would drink alcohol consistently after hours and while operating the boat.

By 2020, she says the situation had become its “worst.” She says Ian neglected safety protocols on multiple occasions. That year, she decided not to work with Pacific Wild again.

“He put us all in danger,” she says.

Andrea is not alone. The Narwhal spoke to more than a dozen contractors and employees who worked with Pacific Wild over the years. Many say they were put in positions beyond their marine experience. More than that, they say they witnessed a wide range of what they considered to be inappropriate behaviour, including verbal and emotional abuse and Ian frequently drinking on the job, including while captaining his boat. In September 2020, Ian publicly admitted he used a seal carcass to attract wolves.

The Narwhal was also alerted to an alleged sexual relationship Ian had with a woman who reported directly to him, which spanned roughly two years. Internal emails show that rumours of the relationship were brought to the organization’s attention in 2019. The woman resigned a year later. When contacted by The Narwhal, she said she could not provide comment.

The Narwhal reviewed an email she sent to Pacific Wild board members and the McAllisters at the time of her resignation in 2020, in which she alleged Ian drank at work and exhibited “anger,” “manipulation” and “emotional abuse.” She said there was a “lack of accountability at Pacific Wild.”

“Because of the lack of policies, and the conflict of interest in leadership, I did not know who to go to for help,” she wrote.

“I am hurt by the fact that I trusted all of you, and the system, to protect me in my work environment, and that didn’t happen.”

“The combination of the power, the shame, the manipulation, and the various levels of isolation, kept me silent, but I will not be silent anymore,” she wrote.

Prior to 2021, Ian was the long-standing executive director and his wife Karen was the organization’s conservation director, making them the two primary managers of staff.

They founded Pacific Wild together in 2008 and have been prominent conservation advocates for decades. Pacific Wild is known, in part, for pushing for the protection of the Great Bear Rainforest, a 64,000-square-kilometre area that hugs the shoreline of B.C.’s north and central coast. Stewarded by First Nations for millennia, the region is famous for the iconic spirit bear, a black bear with a recessive gene that makes it glow white against the mossy forest floor.

As a non-profit organization, Pacific Wild is technically governed by a board of directors. But Ian and Karen both sat on the board from 2008 to 2019 while also leading the organization, so some workers had little faith their concerns would be meaningfully addressed. Workers say it wasn’t always clear who was on the board, partly because the organization does not list board directors on its website.

Despite these concerns, The Narwhal has learned that Pacific Wild board members were alerted to Ian’s conduct at least twice from 2015 to 2020. One worker says the board failed to sufficiently act on her warnings in 2015, and that unsafe practices continued. The Narwhal reached out to board members from this period to find out how they responded to allegations but did not receive comment.

Ian stepped down as executive director on Aug. 16, 2021, with a statement from him at the time saying, “It’s time for me to step away for personal and professional reasons and for a new executive director to take the organization forward.” Ian remains a conservation advisor, listed on Pacific Wild’s staff page, and his photographs continue to be shared regularly by the organization.

His wife Karen, who sat as the secretary and treasurer of the board of directors until late 2020, took over the position and remains executive director today.

For more than a year, The Narwhal has been investigating allegations of poor governance and abuse of power within the organization, and how workers’ safety may have been put at risk. Some people who spoke to The Narwhal say they had a positive experience and did not witness any inappropriate conduct at Pacific Wild. But more than a dozen former workers’ experiences, as well as documents and emails, align in painting a picture of a tumultuous workplace where people regularly felt unsafe and overworked but feared speaking out.

The names of workers who are concerned about the impact of speaking out on their personal and professional lives have been changed. Some of these workers have close personal relationships with one another, which have not been disclosed to protect their identities.

“I’d rather be doing anything than coming forward with this story,” Madelyn, who worked with Pacific Wild for more than a year, says. “But it feels really important to talk about this experience. Because I do feel like it’s a public danger to have these people in positions of power who have escalating patterns of abuse towards the people around them, who are so protected by these organizations and the people around them.”

“I feel like it’s hugely disrupted and damaged so many lives, and the lives of so many up-and-coming conservationists and people who are wanting to do good in the industry.”

Over the course of several weeks, The Narwhal tried repeatedly to speak with Ian, Karen or current or former Pacific Wild board directors, and sent a detailed list of questions outlining the allegations in this story. They did not respond directly — instead, we received an emailed statement from Kirsten Mihailides Public Relations.

“Pacific Wild Alliance does not comment on personnel matters but observes that all organizations face challenges as they renew and grow,” the statement says.

“Ian McAllister led Pacific Wild during its first chapter. While he no longer has any operational or leadership role with the organization, Pacific Wild is energized under its new leadership and focused on continuing its efforts in wildlife habitat protection.”

Over the years, Pacific Wild has brought in millions of dollars for the organization’s advocacy — even receiving endorsement from the likes of Miley Cyrus and Ryan Reynolds. Beyond pushing to partially protect the Great Bear Rainforest, some of its self-proclaimed successes include getting trophy hunting of grizzly bears banned in B.C. and campaigning for the cancellation of the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline, a multibillion-dollar proposal that was scrapped in 2016.

Many sources say Pacific Wild had an ability to share beautiful images that inspire people to care about the region. But former workers question the trade off between compelling conservation campaigns and the toxic environment they say they were exposed to.

“There’s no denying that those images are powerful. But I think for a long time, those beautiful images have been the justification for a lot of the harm that goes on behind the scenes,” one former worker says.

In 2014, when Madelyn began as a volunteer with Pacific Wild, the then-22-year-old diver dreamed of becoming a wildlife photographer. She thought photography was a form of storytelling that could “change people’s hearts and minds.” She was passionate about protecting wildlife in the face of climate change.

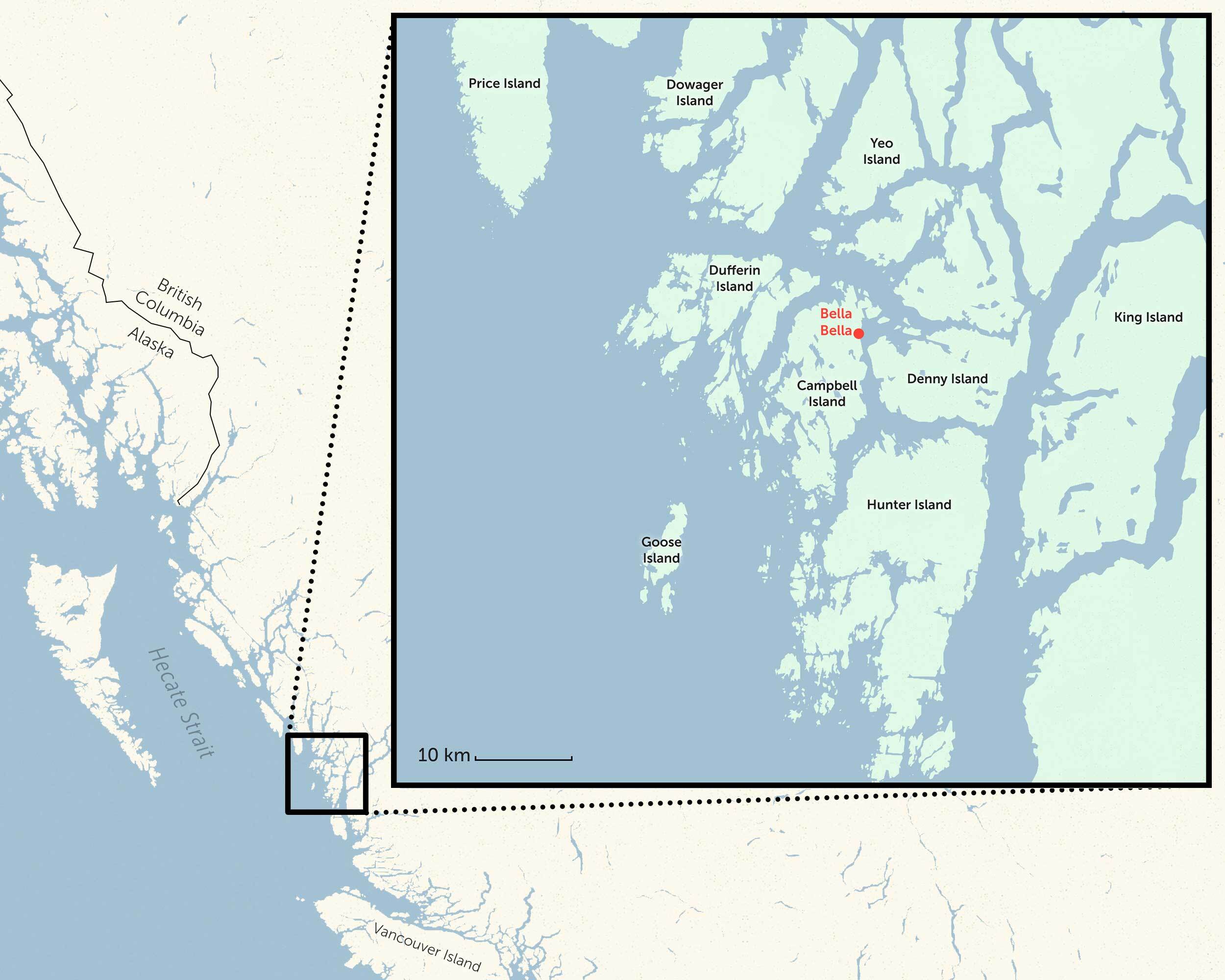

Madelyn travelled some 300 kilometres from Vancouver Island to Denny Island, B.C., Haíɫzaqv territory, to volunteer for the organization. She was excited to help wildlife, as well as learn about photography from Ian.

“It just seemed really fun,” she says. “Until it wasn’t.”

On its surface, the work entailed going on trips to see awe-inspiring wildlife and then sharing those images to promote conservation. When she arrived, she got a sense the rules were casual. The staff seemed cool and young. She says it seemed like a “conservation party.”

She lived on Denny Island in a small cabin with her co-workers, a short distance from the McAllisters’ home where they lived with their two children. The sparsely populated island adjacent to Bella Bella houses about 100 people. Staff and contractors say they worked in close quarters with each other and Ian, often living together on boats, and in isolated areas without signal, sometimes for weeks at a time. They say they largely relied on each other for company and safety.

But working with Ian was different than she expected. She says he seemed cynical and fulfilled a “moody” artist archetype. She discovered the workplace was disorganized, with staff often lacking clear instructions and working in chaotic and demanding conditions.

“Every day, you were just working on something as if it was an emergency,” she says.

To Madelyn, it seemed everyone around Ian accepted that he was dysfunctional and erratic because of his talent as a photographer. Despite his moodiness, she and Ian got along well at first, she says.

“There would be a lot of camaraderie and fun and silliness,” she recalls.

But soon Ian began making negative comments about her work ethic and personality. She says he got angry with her just months into her time there, and things got progressively worse.

Ian would drink on the boat to the point Madelyn was concerned about his ability to meet his responsibilities as captain. She felt Ian would often breach safety norms, including not having appropriate safety equipment or working with unreliable equipment. Other workers had similar experiences in the following years.

Madelyn said the work environment began to take a toll on her mental health, but there was pressure to stay “committed to the cause.” In the face of Ian’s criticism, she worried about “not being good enough.” In hindsight, she sees his comments as gaslighting.

“You just felt like you were doing such important work,” she recalls. Despite the chaos, she joined Pacific Wild as a staff member in 2015 after volunteering for about six months.

Madelyn says Ian showed up at the staff cabin more than once, appearing to be drunk, and yelled at her in front of her co-workers for not working hard enough.

“I could see all the problems, but I could see them through a lens of empathy rather than red flags … like this person’s really angry because I made them angry. I just need to support them more and do better,” she says.

Another former worker The Narwhal spoke with is Taylor, who worked with Pacific Wild for a year. She says environmentalists often feel they can’t “air dirty laundry” because it will “undermine our achievements and goals.” But she says that mindset is hypocritical.

“We can’t be committed to being honest and speaking truth to power about the ways we’re destroying the planet, and turn a blind eye at the ways we might be harming each other in the process,” Taylor says.

“I want those young people who are idealistic conservationists, who are dreaming of making a big difference in the world, to know that if they see something wrong, they should speak up.”

While Pacific Wild did not speak to any specific allegations, its statement includes a description of the workplace.

“The daily operations of Pacific Wild Alliance are run by a group of nearly 20 dedicated staff who care deeply about conservation and the protection of wildlife habitat. The board provides long-term vision to the organization through volunteer directors who generally serve with terms staggered for continuity. The directors work diligently to meet organizational challenges and provide long-term direction. The staff work diligently to develop and carry out conservation initiatives. Working collaboratively, the members of the Pacific Wild team have helped the organization achieve many meaningful victories for the environment and therefore the public interest,” it reads.

Max Bakken, who worked at Pacific Wild for about three years, says he felt professional boundaries were being crossed on multiple occasions. On one occasion, he recalls installing monitoring equipment on remote offshore rocks, called Gosling Rocks, about 40 kilometres southwest of Bella Bella with two coworkers.

“There’s nothing between us and the Pacific Ocean,” he remembers. It was exposed and windy.

Ian, he says, showed up on a paddleboard, with no life jacket, and began criticizing the work they’d done. He wanted them to redo it. Bakken says it seemed Ian had been drinking. One of his coworkers, a woman, tried to defend their work.

“They’re literally yelling at each other … out on this rock in the middle of nowhere,” Bakken says. Meanwhile, he was “racing” to get the work done to allow two hours to return home before darkness set in.

Sometimes, the lax rules meant freedom, which was perfect for an adventurous spirit like Bakken, who has spent his life working on the water and in the woods, and today works as a log salvager. He says he climbed trees alone, 100 feet into the air, while working at Pacific Wild. He enjoyed the adventure. At other times, it felt dangerous.

Madelyn says she was often asked to do things beyond her marine skill level — she worried she might have to take charge of the boat when Ian was drinking alcohol, but didn’t have the expertise required if anything went wrong. She also remembers Ian asking her to navigate tumultuous water alone in a small inflatable dinghy in 2015.

Midway through, she began struggling to follow directions and navigate the small boat, she says.

Bakken remembers seeing Madelyn arrive in Bella Bella that day and being shocked to hear she travelled about 30 kilometres alone. Bakken says he grew up on boats, has done marine emergency training and has a small vessel operator certificate. He spent years commercial fishing and deckhanding. He says Madelyn crossed choppy water that he would “never cross in a small boat,” and calls it “very irresponsible seamanship.”

“As a captain of a boat, [Ian’s] in charge,” he says. “He sent her out across a body of water that easily could have flipped the boat.” Another former worker tells The Narwhal Ian asked them to navigate a dinghy alone in rough conditions years later, and they feared colliding with rocks, and felt “extremely unsafe.”

Back on land, Madelyn constantly felt pressured to work late into the night. Bakken remembers Ian coming to the cabin in a “rage,” appearing to be drunk, banging on the door and calling for Madelyn before storming away. Peter Thicke, who worked at Pacific Wild for more than a year, witnessed a similar incident that summer in which Ian entered the cabin in the evening, asking Madelyn why she wasn’t working, in a “raised voice and very aggressive tone.”

“I remember kind of just being shocked,” Thicke says.

Thicke also loves photography, and he lives and works in Tofino as a city planner today. He thinks boundaries were blurred in the isolated and intimate workplace, and unprofessional and hostile behaviour was normalized. But the workers were passionate about the work they were doing and committed to doing it.

“The workplace, at times, was horrible,” he says. “There’s also times where it, maybe, was one of the most meaningful places you’ve ever been.”

Thicke emphasized the job could be fun and adventurous, and so could Ian. Other workers also recalled the freedom of exploring land and waters, seeing incredible wildlife and getting to know each other while eating sushi at the dock or going to the local pub.

In the moment, Thicke says he rationalized Ian’s behaviour to himself. Only with hindsight did he begin to see the juxtaposition between the good times he had with Ian and the work he was proud of, and the treatment he witnessed.

“[There’s] some interesting conflicts between whatever good that somebody does, versus the harm that they’ve done,” he says.

Meanwhile in 2015, Ian released one of his many books, called The Wild in You, and his famous photo of a wolf peering through the surface of the water was named one of National Geographic’s top pictures of the year.

Madelyn was thinking about leaving Pacific Wild.

At the time, they were actively campaigning to end B.C. ‘s wolf cull — a program that involves government contractors shooting wolves from helicopters in a controversial attempt to protect endangered caribou. The campaign garnered a lot of attention, including from pop star Miley Cyrus, who at the last minute joined Pacific Wild for one of their trips, along with her brother Braison Cyrus. Madelyn says she was the only crew member working with Ian on this trip and, once again, she was put in a position beyond her marine experience.

On the first night she says he effectively left her in charge while he stayed up late with Miley and Braison.

“This was, like, two or three in the morning, and I remember Ian, Miley and her brother were being so loud and just partying on the back deck,” she says.

Miley Cyrus did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment. The other guests on the boat — ecologist Carl Safina and wolf biologists John and Mary Theberge — went to bed early and say they didn’t see or hear Ian up late drinking with the pop star and her brother. They also say they didn’t witness any inappropriate conduct.

“I didn’t see anything that struck me as disrespectful,” Safina says. He has donated to Pacific Wild over the years. “Ian has done a lot for publicizing the coast and its nature and the importance of it. And I always had a high regard for all of that.”

“It was not a party atmosphere,” John Theberge says, adding “we have a lot of respect for Pacific Wild.”

Madelyn says she was awake, working, and experienced it very differently. It was stormy, she recalls, and she didn’t trust Ian would be able to intervene if something went wrong.

“I just remember being really scared about the boat dragging anchor or something happening, and Ian being too drunk and high to do anything,” she says.

With the pressure of Miley’s celebrity status, Madelyn says that when they returned to land Ian pushed her to work late into the night to get a video and press release out for the next morning. She says he came to the cabin and banged on the door again, yelling.

“I was in physical agony from sleep deprivation and overwork,” she says. “I remember crying, sitting at my computer, sobbing.”

Madelyn was feeling burnt out and wrestled with difficult questions: was Pacific Wild helping wildlife or were they building a portfolio of beautiful images? Were they raising money for conservation or were they raising money for their own campaigns?

A couple weeks after the Miley Cyrus trip, Ian was away on a shoot and Madelyn was going through photos when she found a series from 2013 that she says made her heart stop. There was a seal carcass hanging by a rope from a tree. A salmon on the forest floor. Followed by pictures of a wolf looking into the trees, at the seal just out of frame.

Baiting, she thought.

Putting out food runs the risk of habituating wolves to humans. Madelyn had already noticed that wolves Ian frequently photographed on a remote island near Bella Bella seemed habituated to humans. Habituation increases the risk of wolves being shot: either by hunters, because they are less likely to run away from humans, or by conservation officers who deem them a threat to humans. Other people utilize the area too, like local First Nations and kayakers. But these photos appeared to confirm her worst fears — that Pacific Wild was risking the well-being of the wolves it purported to protect.

“All the abuse that I’ve been taking has been for a lie,” she remembers thinking. Those wolves had been put in harm’s way for “professional gain.”

“The veil was really lifted for me that day,” she says.

She emailed Ian on Oct. 17, 2015, asking him to explain what she was seeing. He admitted to hanging the seal, but he said he thought the tide would take the carcass away and he wanted to ensure the wolves had access to prey and to see if there were wolf pups. He maintained photography “was the least of it.”

“I should have left it alone but I put [it] in the tree to see what would happen,” Ian responded in an email reviewed by The Narwhal.

“I could have let the carcass go into the water or could have brought it further up. In this case it was way further up,” he wrote an hour later. “ I think if you were with me you would have agreed to it.”

He went on to say they had done something similar together when they pulled a sea lion up a beach the summer before. Madelyn maintains she saw him move the sea lion, but didn’t participate.

“I would like to think that you know my history with those wolves enough to know that I would not do something to knowingly put them at risk,” Ian wrote.

“Conducting wildlife research, film photography in a non-invasive way has always been a priority and in this case I don’t believe I caused harm but it was a really dumb move.”

Madelyn spent days agonizing before she quit. She wanted to resign immediately, so she retained a lawyer pro bono to get her out of her contract.

Her lawyer wrote a letter on her behalf to the McAllisters and some Pacific Wild board members. The letter outlined the baiting of wolves, safety concerns, consumption of alcohol in the workplace and what she considered harassment. She says she never heard back from the board directly, and The Narwhal was not able to confirm how board members responded. Instead, she received a letter from a lawyer representing Pacific Wild and Ian, who stated her letter was defamatory. Despite this accusation, Pacific Wild’s lawyer proposed a settlement with a confidentiality clause and a non-disparagement clause, which she refused to sign.

“It isn’t defamatory if it’s true,” she wrote in a Nov. 20 email.

“These problems are way bigger than me. My going away will not fix them.”

Still, Madelyn worried that she would be sued if she talked about her experience.

“I was totally scared into silence,” she says.

In emails a couple of months after she quit, Ian told Madelyn to focus on the “positive” and “be proud of all the good work that you have done and will continue to do and try not to be so judgemental.”

“There is so much important work to be done,” he wrote. “This constant criticism of me is draining and takes away from work that I know you care about.”

In 2016, Pacific Wild partnered with another organization to launch a judicial review into the province’s wolf cull. In 2017, Ian published another book, Great Bear Wild: Dispatches from a Northern Rainforest. That September, Pacific Wild released a song tribute from Miley Cyrus about grizzly bears.

Years later, in 2020, Madelyn heard from Pacific Wild workers that issues with the work environment continued after she left, and she felt a responsibility to speak out. In emails reviewed by The Narwhal, she reported Ian to the B.C. Conservation Officer Service for baiting.

The conservation officer service says it cannot confirm or deny whether an investigation into Ian McAllister is underway.

Scott Norris, an inspector with the conservation officer service, tells The Narwhal this is to adhere to privacy laws and to avoid jeopardizing an investigation if it does exist.

He says the service rarely receives reports about baiting, in its colloquial sense — using food to attract wildlife for any purpose. But in the Wildlife Act, the word baiting is specifically associated with hunting.

According to B.C.’s Wildlife Act, a person must not “intentionally feed or attempt to feed dangerous wildlife” or place an attractant “with the intent of attracting dangerous wildlife.”

The minimum fine for placing attractants is $345, Norris says, but it can go much higher — a B.C. wildlife tour company was fined $35,000 in 2019 for attracting black bears with food.

Norris says attracting wildlife causes animals to “develop dependence on humans.” Speaking to wildlife photographers generally, he says he wants people to understand the impact they can have on wildlife, whether they are flying drones over animals or placing attractants.

“They start to learn when that boat pulls up on the beach, for example, that ‘oh, the boat pulled up, that means food’s coming,’ ” he says.“If you’re gonna start doing this stuff, those animals are gonna develop that dependency on you, unsuspecting or not.”

Ian emailed Madelyn after he found out she had reported him. He said a complaint would hurt Pacific Wild’s ongoing court challenge of the annual wolf cull.

“I expect you are aware how this complaint will be used against our collective efforts by government, trophy hunters and all those that oppose our wildlife conservation work,” he wrote on May 21, 2021. “It stands a chance of destroying years of hard work that came with a significant financial investment both on the pending legal front and the public campaign front.”

In September 2020, nearly six years after Madelyn discovered the photos, Ian posted publicly on Instagram about hanging the seal. He admitted he profited from the images — an image was included in his 2014 book Great Bear Wild. With hindsight, he said he should have deleted the image or fully described how it was captured.

“I can say that this is the only image that I have ever taken in over 30 years of photography and film work that could be described in the ‘baited’ category other than throwing tuna in the water to take pictures of sharks,” he wrote.

According to people who worked with Pacific Wild in the years after Madelyn left, Ian continued to bully staff and contractors and drink on the job, and many still felt there was not an avenue to report or address the situation.

In 2018, Rebecca was hired for a short contract with Pacific Wild. She recalls being asked by Ian to navigate Habitat in a rocky, “super narrow” channel, despite making it clear ahead of time she was not experienced enough to navigate in challenging conditions. The boat hit a mud bottom. At first she thought they were stuck, she says, but was relieved when she and a coworker were able to reverse out without issue. Still her mind went to what could have happened — if they had hit a rock, it could have punctured a hole; if they lurched more, someone could go overboard.

She also recalls Ian drinking in the evenings to the point it made her “uncomfortable.” She only spent two weeks with Pacific Wild and never worked with them again. She says she felt ostracized by Ian and the crew throughout her experience.

“Coming out of it, I just felt shattered,” she says. “I held Pacific Wild in really high regard … I felt like everything I believed was a lie.”

Taylor joined Pacific Wild shortly after, and she too was idealistic about helping the environment. Like many of her peers, she says it didn’t take long for her to see the workplace was dysfunctional.

On a week-long shoot in spring 2019, Taylor says Ian was regularly drinking at what she considered “inappropriate times.” She heard him chastise a first-time deckhand, Katie, who was not an employee.

“He was being so forceful and unreasonably loud,” she recalls. “I was really appalled.”

Katie had been excited at the opportunity, but found Ian intimidating almost immediately. She says he gave no direct instructions, but would then be upset if things weren’t done how he wanted them to be.

One night he got mad at her in the galley and, Katie says, she broke down crying. It was such a beautiful place, but the experience was “tainted,” she says.

“I felt attacked,” she says. “I was pissed that that happened. But I was also mostly disheartened … [I] had idolized Pacific Wild and their work so much.” She never worked for Pacific Wild again.

Taylor reflects on her time at Pacific Wild as complicated. She was travelling to beautiful places and making good friends, and she says Ian “could be very charming and complimentary.” But the good was overpowered by the moments she felt unsafe and witnessed what she considered bullying. She began to feel anxious working there. She says one night she began “crying uncontrollably” while trying to talk about work with her partner.

“He was like, ‘if this is how work makes you feel, you need to quit your job,’ ” she says. She left shortly after.

Ian spent years directing an IMAX film about the Great Bear Rainforest, which premiered in February 2019. The film was distributed by MacGillivray Freeman Films and funded by Seaspan, which runs three shipyards along with ferry, tug and barge transportation, and Destination BC, the provincial government’s tourism corporation.

Narrated by Ryan Reynolds, the film features sweeping drone footage of waterfalls and rivers, bringing viewers close up to spirit bears, seals and wolves. High-definition footage of the trees immerses the viewer in the forest.

Throughout 2019, Pacific Wild and Ian promoted the IMAX film. It received many positive reviews, but also drew criticisms.

Jess Housty, a Haíɫzaqv writer and community organizer, thought the movie exacerbated the colonial misconception of untouched wilderness, which ignores Indigenous Peoples.

“I made it official folks so can you please stop calling Haíɫzaqv territory ‘untouched’ now,” she said sarcastically in a tweet accompanied by a photo of her touching her hand to a beach.

In an article by The Tyee, Ian said he worked hard to include “caring, smart young leaders who care deeply about where they are living” from the Gitga’at, Kitasoo/Xai’xais and Haíɫzaqv nations.

On the film’s website, Ian said “it was always essential to us to have the First Nations deeply involved … It was important to us to talk sincerely with the local communities, so we went to each of them and explained what we were hoping to do with the film and then we took their advice and direction.”

William Housty, conservation manager for Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department and Jess’s brother, says this didn’t happen in practice. He says he was disappointed with the framing of the movie and wanted to see more of a Haíɫzaqv perspective.

Multiple people who worked with Pacific Wild say its’ reputation of working with Indigenous Peoples was a big part of why they wanted to work with the non-profit. But William says non-governmental organizations still have a lot of room for improvement in how they work with First Nations.

Non-governmental organizations “still operate as though they think they know what’s best for the First Nations,” often campaigning “at the expense of the nations or their territories,” he says.

William also says he felt “betrayed” when he found out about Ian hanging the seal from a tree because the nation had invested “a lot of time and effort” in its relationship with Pacific Wild. He says baiting is “dangerous” for animals and humans.

“We are open to working with people that have good projects in mind, and they want to build relationships and build trust,” he says. “We don’t want to be burned. We don’t deserve to be burned because we’re just trying to do good.”

He says the Nation’s relationship with Pacific Wild has “dropped off” in recent years.

Pacific Wild did not respond to The Narwhal’s request to comment on what we heard from William by deadline.

Pacific Wild isn’t the first workplace where Ian has come into conflict with his peers.

The McAllisters founded Pacific Wild after leaving the Raincoast Conservation Foundation in 2007. Ian and his father, Peter McAllister, helped co-found Raincoast, a registered charity which conducts advocacy as well as peer-reviewed research of habitat and wildlife. But Ian had a falling out with the other leaders, and Raincoast sued Ian in 2007 for theft of equipment and for using photos that Raincoast said belonged to the foundation.

In the court documents, Raincoast says it conducted the first-ever study of coastal mainland wolves, and the foundation is “the owner of all right, title and interest” of photographs and other materials gathered as part of the project, including photographs taken by Ian. Ian was slated to use some of these photographs in a book without Raincoast, leading the organization to sue him for general damages and profits from copyright infringement.

“[Ian] McAllister admitted on or about May 27, 2007, in writing, that [Raincoast] is the owner of the intellectual property rights … but has refused to pay [Raincoast] a reasonable royalty for his reproduction,” the documents read.

“It’s surprising and disappointing that Raincoast is wasting precious charity dollars on a frivolous lawsuit,” Ian told the Victoria Times Colonist at the time. The dispute was then settled out of court.

The Narwhal asked Raincoast for an interview about Ian’s time at the foundation and the court case but was told “Raincoast can’t speak to any of Ian McAllister’s employment history.”

When Madelyn left Pacific Wild in 2015, she says she was too scared to speak out.

But when she heard from workers years later describing a hostile workplace, she says “it just become so clear to me that it wasn’t going to stop.” She says she knew it wasn’t her fault, but she still struggled with feeling accountable.

“I felt really responsible for not speaking out about it,” she says.

On Aug. 12, 2020, Madelyn filed a complaint with the MakeWay Foundation outlining her experience. MakeWay had a Pacific Wild Fund between 2007 and 2019 to support conservation activities identified by Pacific Wild, which included the Great Bear Education and Research Project, known as GBear.

MakeWay partnered with Pacific Wild on GBear from 2008 to 2019 to collaborate on conservation programming on topics such as oceans, salmon and coasts, according to Alison Henning, director of communications at MakeWay. The foundation officially stopped funding or working with Pacific Wild by the end of 2020. In the time it was active, $2.8 million was dedicated to the GBear project, she wrote in an email.

GBear project workers were employed by MakeWay but some sources tell The Narwhal they effectively worked for Pacific Wild, reporting directly to the McAllisters. Henning says the GBear project also employed Ian between 2013 and 2019.

“MakeWay takes allegations of abusive behaviour and the well-being of our staff very seriously,” Henning tells The Narwhal. The 2020 complaint “was the first time these concerns had been brought to our attention,” she says. However, since MakeWay did not employ anyone at Pacific Wild when the complaint was filed, there was little they could do.

“As we had no formal employer relationship at the time, and were limited in our jurisdiction and ability to take recourse, we were not able to take on a fulsome investigation as we would have if an issue like this arose with current employees,” Henning says. “Despite this, our team held interviews and provided emotional support and coaching.”

Henning says the GBear project was cut because it was “no longer sustainable” financially.

Joanna Kerr, president and CEO of MakeWay, spoke to former workers about their complaints.

“Not only does every person deserve to work in a place free of harm, but work environments should be safe and empowering. Leaders in this sector need to ensure this,” she wrote in an email to The Narwhal.

Pacific Wild Alliance, its full legal name, is a registered society in B.C., which has a board of directors. It registered as a charity federally in Canada in 2019. It is also registered as a charity in the U.S., and that chapter of Pacific Wild has its own board.

Boards of directors are meant to be an arms-length governance structure that provides fiduciary oversight and generally oversees the executive director. Board members are expected to act in good faith and “in the best interest of the corporation,” Tim Richardson, senior manager of the standards program at Imagine Canada, says in an interview. Imagine Canada provides programs and resources to charities and non-profits, which can get accredited by Imagine Canada if they meet its rigorous national standard for best practices. Richardson does not work directly with Pacific Wild as the charity is not accredited through Imagine Canada.

Ian and Karen both sat on the B.C. society board until Ian left the board in 2019.

Richardson says it’s fairly common for an organization’s most senior staff person to sit on the board, but that it’s not best practice. Imagine Canada’s standards program stipulates “no employee may be a [board] director.” He says they will sometimes make exceptions, and it’s possible for an executive director to recuse themselves from discussions about their performance, but that “it’s not advisable.”

“That can create a bit of a contradiction because one of the board’s roles is to supervise the executive director,” he says. “If you are a board member, you’re kind of supervising yourself. You’re providing oversight to your own performance.”

Richardson says it’s likely that Ian left the board because Pacific Wild was trying to get charitable status, and sometimes organizations won’t get approved if the executive director is on the board. In December 2020, Karen also left the board, followed by two other board members. Two new board members were brought in, and the board introduced a conflict of interest clause to Pacific Wild’s bylaws, which had not existed before.

When Ian resigned as executive director on Aug. 16, 2021, he didn’t give details as to why he was stepping down. According to the most recent tax return available, from 2019, Ian is listed as the chairman of Pacific Wild Alliance’s U.S. board, but The Narwhal was not able to confirm if he still sits on that board.

“For over 30 years I have been passionately dedicated to conservation and protecting wildlife and their habitat. For the past 12 years, I have been particularly proud of what we have accomplished at Pacific Wild, and of the incredibly talented and dedicated team we have,” he said in a statement.

“I am very excited about the future and direction of Pacific Wild and know that we have built a very strong foundation to continue being a leading voice for wildlife conservation.”

In its 2021 strategic plan, Pacific Wild identifies organizational resilience and accountability as one of its foundational goals.

It says some of its objectives are “diversity and accountability” in its governance structures, as well as policies to support “onboarding, succession planning and resilience.”

Its second goal is respectful relationships with Indigenous communities, with intentions to “uplift the voices of Indigenous communities,” improve protocols and “unlearn” colonial assumptions.

Max Bakken bikes by the new Pacific Wild office in Victoria and peeks inside. He’s moved on to a new career. He doesn’t follow what the organization is doing anymore.

He says the conservation world gets less scrutiny because of the assumption everyone is doing “good work.” He hopes former workers sharing their stories will change that.

“If you’re out there saving whales and trying to protect wolf habitat and trying to save animals, I think we have a bit of moral blindness about that. We just assume that those people are inherently good,” he says.

But people doing “good work” aren’t immune to the same failures seen in other industries, he says. People want so badly to be a part of the non-profit sector, they put up with treatment they wouldn’t otherwise, Bakken says.

People need to receive “a living wage and be treated well in that position, not like you’re just replaceable,” he adds. “That’s what I would like to see change.”

He encourages people interviewing for new jobs to ask about the structure of the organization they’re applying for, including who is on the board.

Madelyn has moved on to a new career as well. But she still wants to see a change.

“When something like this carries on and is enabled by the board of directors and all people in the organization, it just contributes to a culture where this is happening everywhere,” she says.

“I felt silenced in a lot of ways … I was silent for a long time,” she says. “Other people got hurt as a consequence.”

“I would risk a lot to stop that from happening again.”

Editor’s note: A member of The Narwhal’s board of directors, Lauren Eckert, is a Raincoast conservation fellow. As per The Narwhal’s Code of Ethics, the board of directors is not involved in day-to-day news operations.

The Narwhal has received funding through MakeWay Foundation, previously known as Tides Canada, including for reporting on the Great Bear Rainforest. As per our donor transparency policy, all of The Narwhal’s funding is disclosed annually.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits