Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Patagonia’s founder Yvon Chouinard made headlines recently with the decision to give his family’s US$3 billion company, and its future profits, to the fight against climate change. In his words, “Earth is now the company’s only shareholder.”

Climate policy advocates celebrated the decision. Each year, US$100 million in company profits will go to the Holdfast Collective, a U.S. nonprofit working for climate action and policy advocacy. Its legal status as a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization allows it to directly lobby on U.S. climate policy.

Patagonia has always been a pathbreaker. Since 1985, the outdoor clothing company has donated one per cent of its sales to environmental causes. In 2002, it helped found the business alliance 1% for the Planet to inspire other companies to follow suit.

Patagonia has also shared product innovations, like its plant-based neoprene, with its competitors in hopes of accelerating more sustainable practices. Other initiatives include its certification as a B Corporation, certifying Patagonia as a company that is committed to the common good, and its used apparel marketplace Worn Wear.

But its recent decision is on another scale entirely. Could it help redefine the gold standard of business responsibility?

Tensions between profits and the planet abound in business. Much management scholarship has focused on identifying win-win scenarios where profit and sustainability coincide, including getting eco-conscious consumers to pay more for sustainable products and saving costs by making operations more resource efficient.

In many instances, however, a win-win scenario is not an option. Companies then face tough choices about striking a balance between profit and sustainability.

Patagonia has long grappled with this trade-off, often in public and eye-catching ways. Its 2011 Black Friday ad implored customers not to buy its best-selling jacket due to its environmental impacts. (Ironically, the ad quadrupled the company’s sales). Patagonia continued this pattern in 2020 when it ran an ad in the New York Times about the need to tackle the climate crisis.

Chouinard mused in a 2013 blog post that “making things in a more responsible way is a good start, but in the end we will not have a ‘sustainable economy’ unless we consume less.” He also expressed the hope that “Patagonia can find a way to make decisions about growth based on being here for the next 200 years — and not damaging the planet further in the process.”

A major barrier for sustainable companies is the assumption of shareholder primacy — that managers must maximize profits on behalf of the company’s owners. Shareholder primacy is particularly pronounced in publicly listed corporations. This is a major reason why Chouinard avoided taking Patagonia public and put a purpose trust in charge instead.

A trust or foundation running a for-profit company is not a new idea. In Denmark, and other Northern European countries, foundation-owned companies like Carlsberg and Ikea are much more common. Studies show that the performance of foundation-owned companies is often on par with investor-owned companies.

Foundation-owned firms are rare in the U.S. Regulations introduced in 1969 to reel in the perceived power of foundations imposed a stiff tax on foundations that owned over 20 per cent of a for-profit company. But in 2018, the Philanthropic Enterprise Act removed these obstacles under specific conditions.

These legal changes set the stage for Patagonia’s model. Ownership of the company is divided to give the voting stock to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, while the non-voting stock (which receives the company’s annual profits) goes to the Holdfast Collective.

But this new model comes with potential risks. If it becomes widely adopted, it could be used as much to oppose progressive climate policy as to advance it. Dedicating profits to an organization that can advocate for political causes and candidates may be viewed as a new version of philanthro-capitalism where ultra-rich individuals donate money to advance the causes they care about.

The growing influence of philanthro-barons and private foundations as interest groups in U.S. politics could undermine democratic processes.

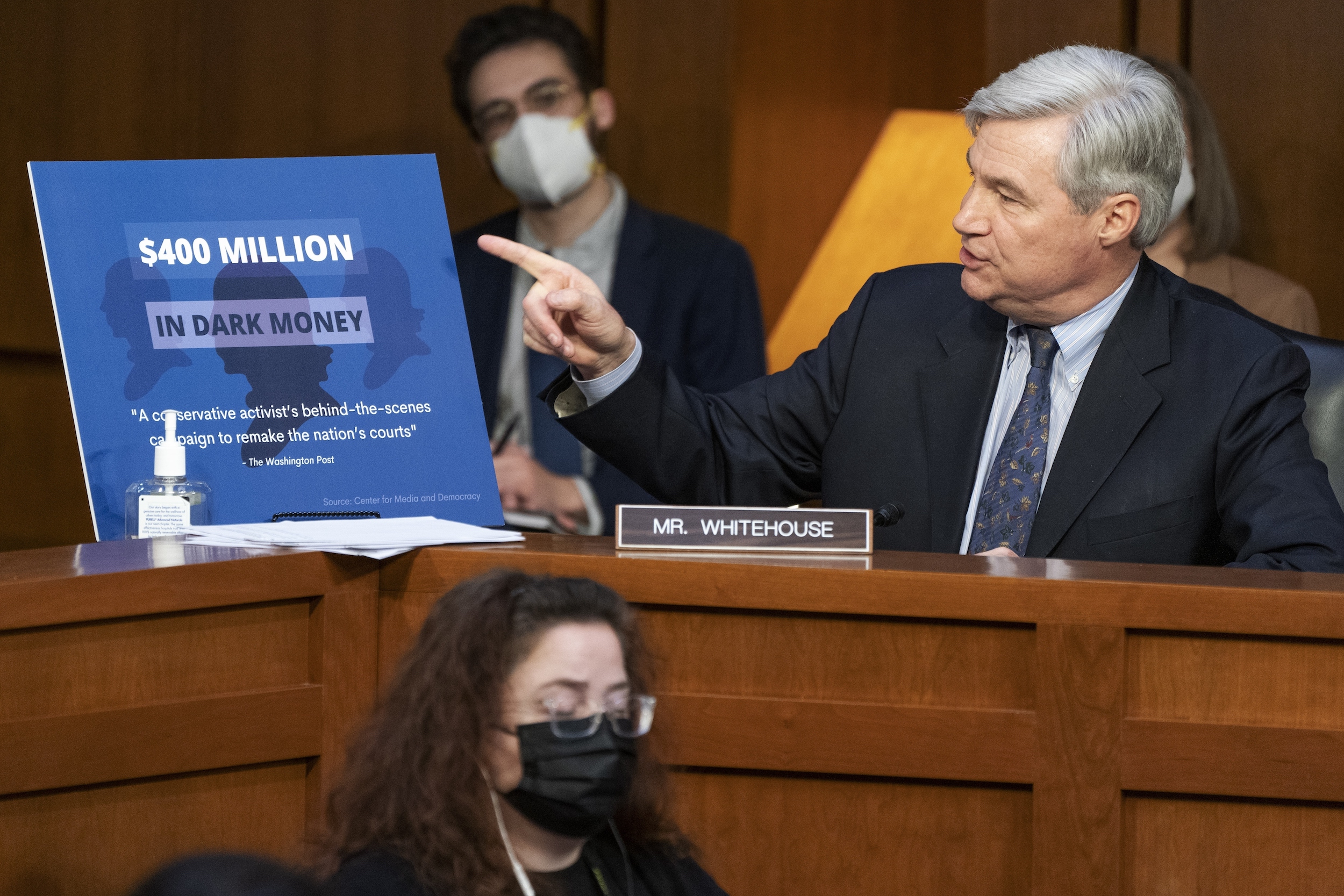

The influence of private money on U.S. politics has only accelerated since the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision that struck down bans on private funding of election campaigns. It facilitated billions of dollars of spending by corporations and other outside groups in recent U.S. elections.

Companies purely dedicated to advocating for their political cause might further accelerate this arms race on both sides of the political spectrum.

Can Patagonia’s model truly solve the tension between profit and the planet? Could it become a new gold standard for business responsibility? This will depend on the balance between its environmental impacts and the social good created via its products and advocacy.

Patagonia’s next moves will determine the actual impact of Chouinard’s decision. Will Patagonia experience pressure to grow its profits to further fund the Holdfast Collective? How will the Purpose Trust interpret the company’s stated purpose of being “in business to save our home planet?”

The company acknowledges the new ownership model “is not an excuse to ignore the real tension we’ll continue to face between growth and the environmental impact of our operations.” For now, this recognition and transparency positions it as a clear model that raises the standard for how to think, talk and act about business responsibility.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits