The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

On a warm summer evening, a flash of heavy rain breaks open over Derek Sutherland’s home in Peguis First Nation.

His doors beat open and shut in the wind; mist sprays into his kitchen and living room. He descends into the basement, where a few inches of water already sit on the concrete floor. Sutherland grabs a long-handled squeegee and begins sweeping the water towards a hole in the floor where two submersible pumps sit ready to move the water away from the home.

Sutherland has lived in this home since he was five years old — he’s in his 50s now. It was his mother’s house and her old family photos still hang on the kitchen walls. The house’s persistent mould made her sick. She has since moved to Winnipeg.

Over the last 20 years the home has weathered numerous floods but none as bad as this spring’s. Sutherland says his basement has filled with water nearly 20 times since April. Each time the waters rise, he heads downstairs, turns on the pumps and sweeps the water away.

“I don’t have nowhere else to live,” he says. “So, I have no choice but to try to fight for it.”

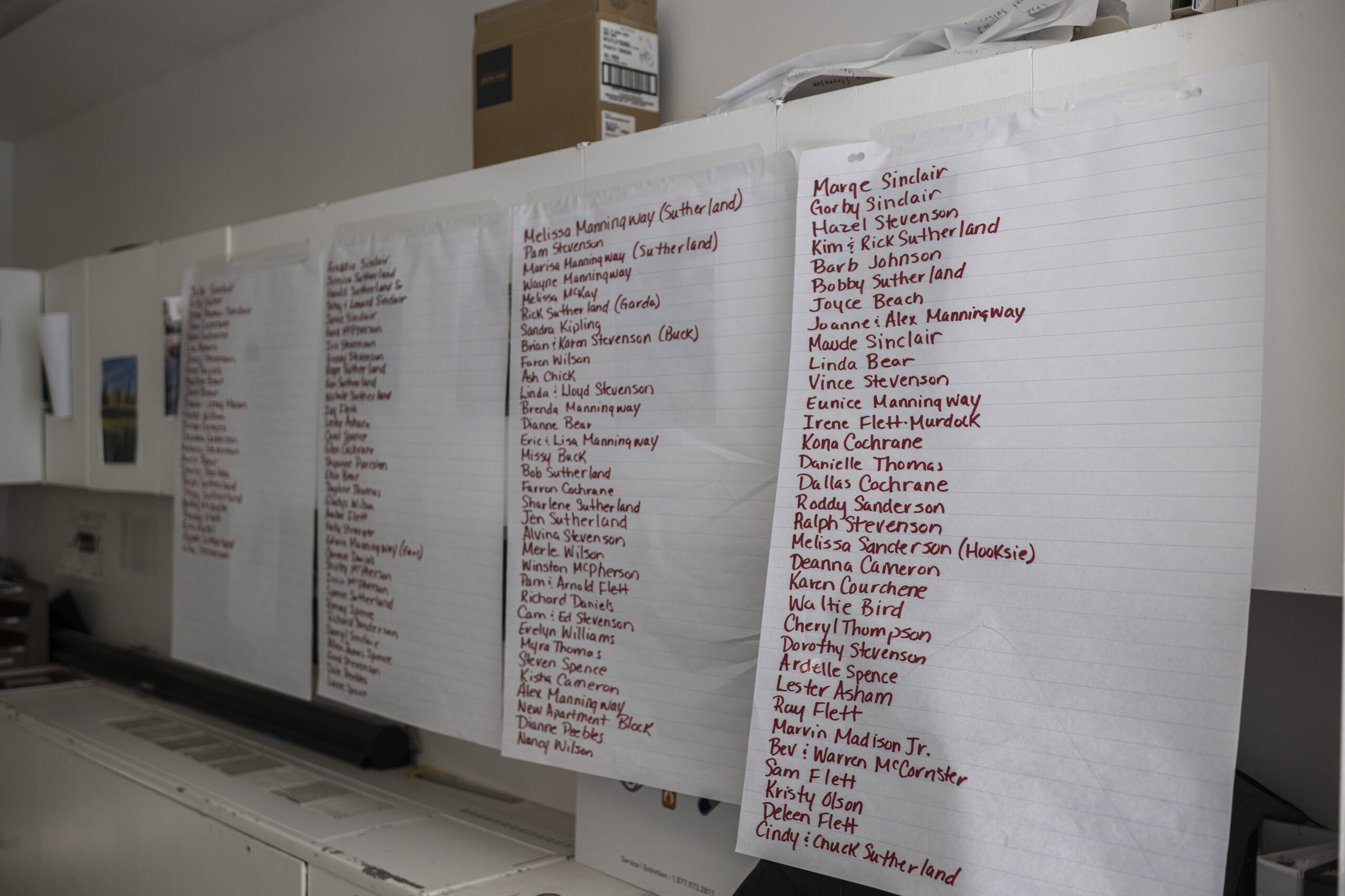

Sutherland is one of hundreds of Peguis residents facing an impossible choice as the community tackles its fifth major flood in 20 years: indefinitely evacuate their flood-prone homes or stay to fight the floodwaters.

Staying and fighting can feel like a losing battle. Peguis has faced major flood events that required evacuations in 2006, 2009, 2011 and 2014. Each flood brings a new wave of damages while successive provincial and federal governments have failed to provide enough funding and support for the community to fully recover, let alone to protect itself from the next flood.

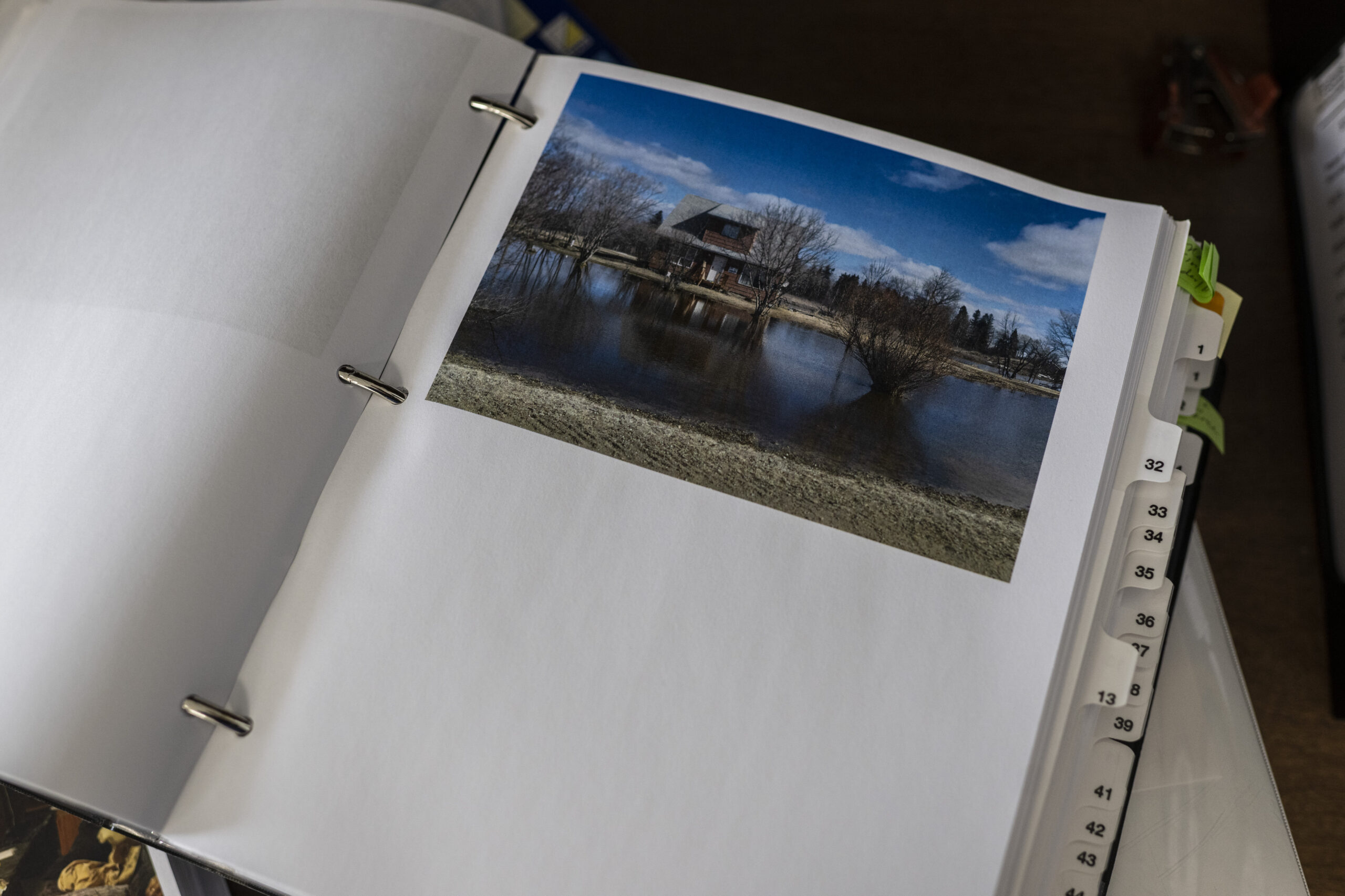

Peguis is the largest First Nation in Manitoba, with more than 10,000 members and over 3,000 permanent residents. It’s located on a broad swath of low-lying land tucked between Manitoba’s two largest lakes: Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba. The community’s nearly 950 homes are spread out across more than 76,000 acres of land, connected by hundreds of kilometres of gravel road. The community sits in the Fisher River watershed, and the river itself winds through the heart of the community. Because of its low elevation, its proximity to the river and the marshy character of what’s known as the Interlake land, Peguis is prone to floods.

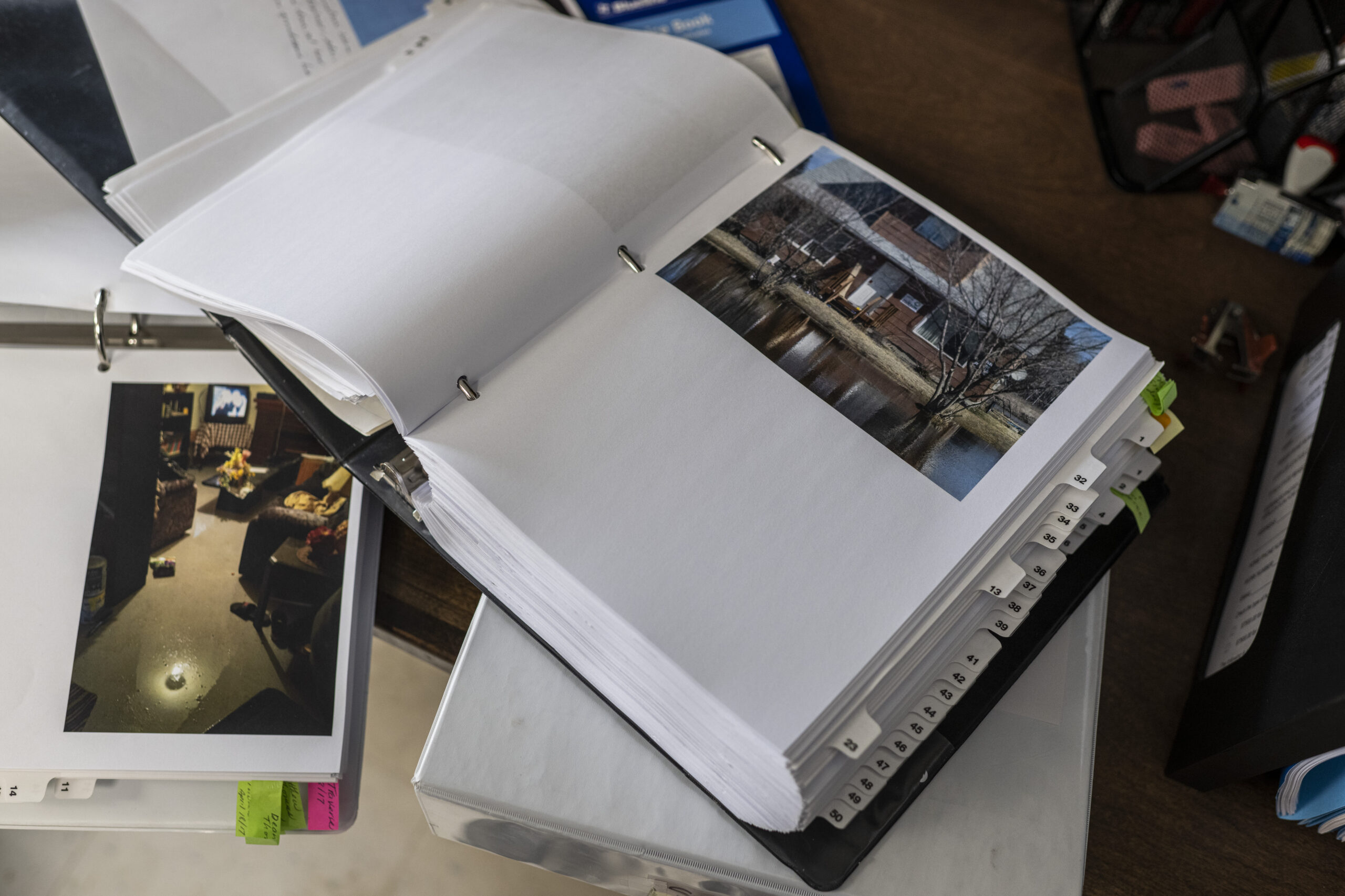

But this year, the damage is unlike any before. The community was hit in April by a one-in-200-year flood that damaged over 300 homes, wiped out sections of roadway, including the community’s lone major highway, and overwhelmed brand new sewage and septic systems, Chief Glenn Hudson says. More than 2,000 people were forced to evacuate and take up long-term residence in hotels across the province. Many evacuees are unsure when they’ll be able to return home — if at all.

Hudson estimates the cost of damages will reach $300 million this year, but as of yet, he says, “we haven’t had any commitment in terms of financial support” from the federal government.

Instead, community leaders have been left scrambling, making use of limited resources to manage the emergency response, secure housing and repair or replace what has been lost.

The last decade has been particularly hard on Peguis, housing and emergency management director William Sutherland says. The major floods in 2011 and 2014 were followed by a lesser flood in 2017 that still overwhelmed the river and leaked into basements. There was a major power outage following a 2019 storm, the COVID-19 pandemic and now a historic flood made all the more challenging by relentless rains. Each time the waters recede, Peguis is left to pick up the pieces.

“We’re like a little hamster on a wheel, going full tilt but not getting anywhere,” Sutherland says. “We just constantly cannot catch a break.”

Months after the initial flood, the damage remains: stagnant pools of water in yards; washed-out gravel roads; mould-streaked basement walls that impact the air quality and health of residents.

In one home, the mould stretches nearly a metre up, leaving a dark shadow just below the basement windows. The house is likely a write-off, a staff member from the community’s housing department says, because the main floor has been damaged by the moisture.

The homeowners, Bev and Warren McCorrister, were forced to leave. Bev has been staying in a Selkirk hotel, while Warren is living next to the house in a trailer donated by the band council. He stayed to fight the waters, replacing submersible pumps, piling up sandbags and bailing out the basement with pails. It wasn’t enough.

“Nothing could stop that water from coming in,” says Bev’s sister Thelma Spence, sitting in an office at the Peguis recreation centre where the flood team has set up its emergency centre. “I don’t know whether they’ll ever come home, to tell you the truth.”

This year’s flood forced her family apart. Spence and her mother stayed behind in their respective homes but two of her sisters were forced to evacuate, as were Spence’s six children and 15 grandchildren. Her mother has been lonely, Spence says, while she herself has been wracked with worry for her family’s safety and well-being as they face the myriad complications of evacuation.

“It’s breaking their spirits,” Spence says of family members stuck in hotels. “They want to come home but they don’t have a home to come back to.”

Like many First Nations across Canada, Peguis is facing a housing crisis. Chief Hudson says the community has a young and growing population, but housing infrastructure hasn’t kept pace; many homes are overcrowded and insufficient. Flooding only deepens the existing crisis.

After a flood, the community can apply for funding from Indigenous Services Canada to repair damaged homes, Sutherland says, but those funds are earmarked specifically for existing dwellings. Sutherland says Peguis needs significant capital funding to replace the homes that have been lost, but that money has not been made available.

For its part, Indigenous Services says it has spent upwards of $28 million, as part of a 2010 commitment to “protect homes through replacement or repair.” Those funds have been used to “flood proof” and repair the community’s 75 most vulnerable homes, to demolish damaged homes and to purchase and install approximately two-dozen “ready-to-move” housing units.

Chief and council, however, say the federal government’s investment falls far short of the community’s needs. With only around a dozen homes provided after each flood, and hundreds lost to mould and water damage, Peguis has faced a net loss of housing over the last two decades.

“Our people deserve more and they deserve better,” Hudson says. “The solutions are there, but the commitment is needed by people in power to show there is concern for our First Nations people in this country.”

Over the last decade, Peguis leadership has repeatedly asked the federal government to invest in long-term solutions. In 2008, the province commissioned a study, funded in part by Indigenous Services Canada and conducted by the engineering firm AECOM, that explored flood mitigation strategies for both Peguis and nearby Fisher River Cree Nation.

The study proposed four possible solutions: upstream water retention; raising vulnerable homes above the flood levels; building a diversion channel for the Fisher River; or building dikes along the riverbanks or around clusters of homes.

The report found the only “economically justifiable” option was to build a $90-million dike along the Fisher River corridor and move homes, bridges and other key infrastructure away from the banks.

But Hudson says a diversion channel would be more cost effective and would prevent families who have lived along the river for generations from being forced to move their homes. Hudson says the community advocated in 2009 for a diversion channel and retention ponds, which he estimated would cost around $50 million at the time, but those solutions were never put in place.

The provincial government also has been reluctant to make a commitment. However, a spokesperson says the province has spent more than $10 million since 2006 on “improvements,” such as drainage upgrades along the highway, a drainage study and bridge repairs, but could not provide specific details about the cost of each project, or when the funding was disbursed. The province maintains that it is working with Peguis and Ottawa to develop permanent solutions.

Hudson emphasizes the federal government is responsible for mitigating the impact of the floods, in large part because, more than a century ago, Canada moved the people of Peguis from their original home in St. Peters, which Hudson calls “some of the most productive farmland in all of Manitoba,” to the flood-prone Interlake land where they live today.

Although the federal government staged a vote about the move in 1907, historians have described the process as intentionally confusing, and the surrender was eventually declared invalid.

“That location was taken from us illegally by the federal government,” Hudson says. “And we were relocated to present-day Peguis.”

Addressing the community’s long-term flood damages and housing concerns is key to reconciliation, Hudson says, and the government’s failure to meet the community’s needs suggests a lack of concern for Indigenous peoples.

“That’s part of reconciliation: they gotta live it, they gotta breathe it, they gotta be committed to it,” he says. “And I think that’s one of the reasons why we haven’t had a commitment financially to address these solutions, is because of the attitudes toward First Nations people.”

In an email statement, Indigenous Services provided a list of projects it has funded to help Peguis repair and rebuild following flood events, but stopped short of promising funding for permanent solutions.

“While significant investments have been made for short- and long-term flood mitigation at Peguis First Nation, we recognize more needs to be done,” a department representative said. “Discussions with the First Nation on future long-term flood protection are ongoing.”

More than $3 million since 2015 to help with flood preparation and response efforts like sandbagging, ditch cleaning, snow removal and water pumping,

$1.9 million for flood recovery efforts like home inspections and repairs,

More than $2.5 million for preparation and recovery directly related to the 2022 flood

$850,000 for river crossing upgrades and flood gates,

More than $4.5 million in 2021 for a multi-year protection process that includes raising wells and septic-fields above 100-year-flood levels, and repairing an existing flood dike. The department expects to contribute another $2.1 million to this project in the 2022-2023 fiscal year.

For many Peguis residents whose homes have been repeatedly damaged, there is no guarantee they’ll ever be able to return. With the glacial pace of repairs and new builds, some residents find themselves evacuated for years.

Dysin Spence was 11 years old when his family was forced to leave his childhood home and take up residence in a Winnipeg hotel. Eight years later, his house remains condemned, sinking on its rotting, wooden foundation. He’s not sure when his family will be able to come home.

“It basically tore our whole family apart,” says Spence, who now lives in a nearby community. “We should be in our home communities and we should be with our family — not being taken away from the reserve.”

Spence and his family were first evacuated during the 2014 flood. After six months living between two Winnipeg hotels, the family was moved into a four-bedroom house in the city subsidized by payments from the Red Cross, he says. But within a couple years, the strain of a life disconnected from their home community began to take its toll.

“There was no support for us, there was nothing,” Spence says. “All we got was a little bit of support for rent costs, but it was really stressful. I started to lose myself — I lost my spirit.”

Spence says his new school life was rife with racism and mistreatment from teachers and peers. His home life had become unstable, his social life unfamiliar and challenging.

He spent several years in and out of the youth criminal justice system between the ages of 14 and 18, spending stints in isolation, unable to connect with his family or his culture.

“That was really hard on me, too, as a 14-year-old going into that, and being away from my reserve, and then going into the youth criminal justice system and being locked away from my mom,” he says.

In the years since the evacuation, Spence has been chasing down band leadership, the Red Cross and Indigenous Services seeking compensation for his family’s lost home. Indigenous Services offered $45,000 to clean and repair the home, but Spence says he’s never seen those funds or repairs.

Hudson says $45,000 is nowhere near sufficient; the house is unlivable, infested with mould, and would need to be demolished and rebuilt entirely. Indigenous Services, Hudson says, has not committed to providing the Spence family with a new home.

“I still don’t even know if I’m going to get a house or my mom or my family is going to have a place to live, and I’m scared that it’s gonna keep dragging on and on,” Spence says. “We just all want to be home already.”

Even when homes are replaced, there’s no guarantee the new builds will withstand future flooding.

Tracy Govereau, her boyfriend and her three children were forced to evacuate more than a decade ago. Their home had been built on a wooden foundation, but the rising water levels and saturated ground caused everything — even the surrounding gravel — to be overcome with mould.

Govereau and her family moved into Winnipeg hotels for what would become a two-year stay. She had to give up work, taking care of her kids full time as they struggled to adapt to new schools. In the meantime, she waited for news on the repair of her home. Those repairs never came. Instead, she was moved to a new house situated on higher ground.

“I thought it was far enough up the ridge, but it turns out it wasn’t,” Govereau says.

As floodwaters rose again this year, so too did the mould on the basement walls. Govereau says it’s now a metre high and is afraid it will reach the home’s main level.

“About every rainstorm, I flood,” she says. “Now I don’t know if my house will be condemned, but I know my kids can’t go back there.”

Govereau and her children, now teenagers, are again living out of a Winnipeg hotel. They’ve been there for three months, crammed into one room. She makes the trek to Peguis every few days to check on the home and to chip away at the cleaning.

“I must pour probably about 50 pails of water out of my basement every time I have to clean up just a little bit,” she says.

Her biggest worry is the children’s health. Her kids have gotten sick from the mould in the past, and already struggle with asthma and other respiratory issues.

In 2019, the Assembly of First Nations began pressuring the federal government to address the health impacts of mould in First Nations housing. At the time, the federal NDP released data from Indigenous Services that showed mould was found in homes in every First Nation the department surveyed, including 53 of 63 Manitoba First Nations that participated.

Health Canada warns mould can seriously impact indoor air quality and lead to “allergic reactions such as asthma … non-allergic reactions such as headaches, and other symptoms (including) lung and breathing infections,” adding children and the elderly are more susceptible to mould-related illness.

While no specific data exists on the prevalence of mould-related illness in Peguis, a Manitoba First Nations regional health survey completed in 2016 found nearly 40 per cent of people surveyed had mould in their homes, and that adults with one or more chronic health conditions were more likely to live in houses with mould or mildew than those with no chronic health conditions.

While she waits for support from the band council, Govereau has been cutting out moulded walls herself “because if I don’t do that, who else is going to do it for me?”

“I don’t know what to do, I’m just trying to protect my house,” she says. “Whatever I’m doing, it’s for my kids, for their future.”

During the long periods spent away from the community, evacuees are supported by teams from the Canadian Red Cross, who are in turn funded by Indigenous Services.

The Red Cross has received upwards of $11 million this year to provide on-site supports at evacuee hotels, including facilitating activities for community members, providing games and toys for children and co-ordinating meals and supplies, such as hygiene kits, diapers, formula, for those staying in hotels and private accommodations. The Red Cross also provides rental assistance, but families are never sure when those supports will run out.

“I’m in a cell. I feel like I’m in jail.”

Se’Kwun Cochrane, Peguis First Nation evacuee

Se’Kwun Cochrane, who has been living in Winnipeg hotels since April, says she’s met countless community members who have been stranded for years.

“There’s still hundreds of people that never got housing,” Cochrane says on a call from her hotel room. “They’re stuck in Winnipeg on their own, they no longer have funding because that just got cut off after how many years, and now these people are struggling, and some of them are now homeless. They don’t know what to do and the reserve is not helping at all.”

Within the hotels, Cochrane says evacuees live a life riddled with instabilities: Residents can be asked to pack their belongings and switch hotels within a matter of hours; Red Cross meals are restricted to specific timeframes; treatment from hotel staff can be cruel.

The culture shock of living in a busy city can also prove stressful. Hudson says community members have died from overdoses while living in the hotels, others have become involved with the criminal justice system.

Cochrane, who suffers from a health condition that has indefinitely delayed her return to Peguis, says she’s taken to staying in her room to avoid racism and stereotyping from hotel staff. In one incident, she says, she was initially denied service in the hotel restaurant and was then asked to pay before receiving her food.

“I don’t go down there anymore. I just refused,” she says. “I’m in a cell. I feel like I’m in jail.”

Cochrane had only lived in Peguis for five years — she grew up in Ottawa with her mother after leaving the reserve as a child — but returned to reunite with her siblings.

When the river began to rise, Cochrane called the band’s flood centre asking for a sandbag dike to be built around her home. The centre said they couldn’t help; she was on her own. Owing to her poor health, Cochrane could neither sandbag her home nor stay in the community.

“So now I’m stranded here,” she says.

Since April, Cochrane says she’s been shuffled from hotel to hotel, leaning on her sister for meals and medical support. She longs to return to Peguis, to be with her family and take part in ceremony, like an upcoming Sundance, but isn’t sure when she’ll be cleared to travel back.

“I miss my bubble back on the reserve because I feel safe there, I don’t feel safe now,” she says. “You know, people don’t think we notice the looks, but we see that. We see the looks, we feel the looks and you know, it’s not welcoming.”

As Peguis works to rebuild after this year’s flood, there is a frustration with a perceived lack of support from those in charge. Many residents blame the community leadership for what they believe is a lack of preparation and funding. In turn, band leaders charge both levels of government bear the brunt of responsibility for the ongoing damages.

In the case of this year’s flood, emergency operations manager William Sutherland says the federal government declined funding requests that would have helped the community prepare in advance.

Every year, Sutherland explains, the community does its own flood risk assessment before the spring melt. This year, Peguis expected a major flood event and submitted a proposal to Indigenous Services for extra funding to buy submersible pumps, tiger dams (a type of temporary inflatable dike) and other flood protection, he says. The request was denied when the province’s February forecast showed a “low risk” of flooding in the Interlake region.

When the water came, emergency teams focused their attention initially in the southern region of the First Nation, sandbagging, evacuating the most flood-prone homes and replacing water pumps, Sutherland says.

But the waters rose quickly, swallowing the central region and prompting a “scramble” to provide emergency response. By the time the waters reached Peguis’s northern boundary, “there was nothing we could do,” Sutherland says.

The roads were washed out, heavy trucks couldn’t travel on the soft gravel or fight the current.

“Nobody knew the height of the water,” he says. “It’s too dangerous to send emergency [responders] quickly to that area.”

Sutherland is frustrated with the government’s lack of response. He’s long wondered why the government is reluctant to fund permanent repairs to homes and critical infrastructure. In the meantime, he bears the responsibility of managing a community full of trauma and pain.

“It’s the stress of not only dealing with the effects of rising water on the community,” he says. “But also dealing with angry people, upset people, hurt people, crying: ‘when’s help going to come?’ ”

Because of the severity of this year’s flood, Hudson is optimistic the government will pay heed to his community’s pleas, but notes there’s no longer time to abide the slow trickle of government bureaucracy.

“Rather than paying out these costs as far as replacing homes and fixing homes that have been flooded multiple times, we have to look at a much broader and a much more resilient strategy that’s not going to allow flooding in our community,” he says. “We have to complete this work in a matter of three years, not 11, 12 or 13 years.”

In the short term, Hudson says the community is hoping to build a new emergency centre, “because our emergency centre just doesn’t accommodate the amount of work that is required to keep our people safe and our places safe.”

But in the long term, Hudson and council are working on a submission to federal and provincial governments outlining the scope of work needed to repair and improve critical infrastructure affected by the floods.

A team of band-selected engineers, hydrologists and developers are outlining costs for the new emergency centre, along with better roads, another new sewage system, new community buildings and, most importantly, homes. And they’re not giving up on the promise of permanent flood protection.

Back in Derek Sutherland’s waterlogged basement, he points out two streaks of orange spray paint on the concrete walls. They mark cracks in the foundation that have been there for decades but have never been fixed. It’s where the water seeps in during the floods.

Sutherland has been protecting his home on his own for many years. He used to volunteer with the flood relief teams, so he knows how to keep the worst of the water at bay. He won’t evacuate because he doesn’t want to live in a faraway hotel. Leaving would also mean giving up his job at the Peguis school.

He has been waiting years for a permanent solution that will preserve his home — and the memories that come with it. Sutherland says he’s asked for help protecting his home from the ongoing floods and is running out of options.

“I can’t leave. I don’t want to leave,” he says. “It’s my mother’s house, all our assets are in here — I’m fighting for my family.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...